Paper Moon (film)

| Paper Moon | |

|---|---|

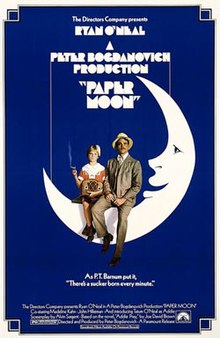

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Bogdanovich |

| Screenplay by | Alvin Sargent |

| Based on | Addie Pray by Joe David Brown |

| Produced by | Peter Bogdanovich |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | László Kovács |

| Edited by | Verna Fields |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $30.9 million[2] |

Paper Moon is a 1973 American road comedy-drama film directed by Peter Bogdanovich and released by Paramount Pictures. Screenwriter Alvin Sargent adapted the script from the 1971 novel Addie Pray by Joe David Brown. The film, shot in black-and-white, is set in Kansas and Missouri during the Great Depression. It stars the real-life father and daughter pairing of Ryan and Tatum O'Neal as protagonists Moze and Addie.

Tatum O'Neal received widespread praise from critics for her performance as Addie, earning her the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, making her the youngest competitive winner in the history of the Academy Awards.

Plot

[edit]In Gorham, Kansas, circa 1936, itinerant con man Moses Pray meets nine-year-old Addie Loggins at her mother's graveside service, where the neighbors suspect he is Addie's father. He denies this, but agrees to deliver the orphaned Addie to her aunt's home in St. Joseph, Missouri.

At a local grain mill, Moses convinces the brother of the man who accidentally killed Addie's mother to give him $200 for the newly orphaned Addie. Addie overhears this conversation and, after Moses spends nearly half the money fixing his old Model A convertible and buying her a train ticket, she demands the money as rightfully hers, whereupon Moses agrees to let Addie travel with him until he has raised back the full $200 to give to her. Thereafter, Moses visits recently widowed women, pretending to have previously sold expensive, personalized Bibles to their deceased husbands, and the widows pay him for the Bibles inscribed with their names. Addie joins the scam, pretending she is his daughter, and exhibits a talent for confidence tricks, such as selling Bibles and the quick change scam. As time passes, Moses and Addie become a formidable team.

One night, Addie and "Moze" (as Addie addresses him) stop at a local carnival, where Moze becomes enthralled with an "exotic dancer" named Miss Trixie Delight and leaves Addie at a photo booth to have her photograph taken alone (of herself sitting on a crescent moon, to suggest the film's title). Much to Addie's chagrin, Moze invites "Miss Trixie"—and her downtrodden teenage maid, Imogene—to join Addie and him. Addie soon becomes friends with Imogene and jealous of Trixie. Imogene reveals that Trixie works, at least occasionally, as a prostitute, and it is suggested she has a venereal disease causing her a frequent need to urinate. When Addie subsequently discovers that Moze has spent their money on a brand-new Model 48 convertible to impress Miss Trixie, she and Imogene devise a plan. They convince a clerk at the hotel where the group is staying to visit Trixie. Addie then sends Moze up to Trixie's room, where he discovers the clerk and Trixie having sex. Moze promptly leaves Miss Trixie and Imogene behind, with Addie leaving Imogene enough money to pay for her own passage home.

While staying at another hotel in a rural area, Moze uncovers a bootlegger's store full of whiskey, steals some of it, and sells it back to the bootlegger. Unfortunately, the bootlegger's twin brother is the local sheriff, and he quickly arrests Addie and Moze. Addie hides their money in her hat, steals back the key to their car, and the pair escape. To elude pursuit, they trade their new car for a decrepit Model T farm truck after Moze beats a hillbilly, Leroy, in a "rasslin' match."

Moze and Addie make it across the state line to Missouri, where Moze sets up another swindle, only to be caught again by the sheriff and his deputies; outside their jurisdiction and unable to make an arrest, they beat Moze and rob him of his and Addie's savings. Humiliated and defeated, Moze drops Addie at the house of her aunt in St. Joseph, but a disappointed Addie rejoins him on the road. When he refuses her company, she reminds him that he still owes her $200 and points out that his truck has just rolled away without him. They catch the truck and leave together.

Cast

[edit]- Ryan O'Neal as Moses "Moze” Pray

- Tatum O'Neal as Addie Loggins

- Madeline Kahn as Trixie Delight

- John Hillerman as Deputy Hardin/Jess Hardin

- Burton Gilliam as Floyd

- P.J. Johnson as Imogene[3]

- James N. Harrell as The Minister

- Noble Willingham as Mr. Robertson

- Randy Quaid as Leroy

- Hugh Gillin as 2nd Deputy

- Rose-Mary Rumbley as Aunt Billie[4]

Production

[edit]Director

[edit]The film project was originally associated with John Huston and was to star Paul Newman and his daughter, who was a child actor at the time named Nell Potts. However, when Huston left the project, the Newmans became dissociated from the film as well.[5] Peter Bogdanovich had just completed What's Up, Doc? and was looking for another project when his ex-wife and frequent collaborator Polly Platt recommended filming Joe David Brown's script for the novel Addie Pray. Bogdanovich, a fan of period films, and having two young daughters of his own, found himself drawn to the story, and selected it as his next film.[6]

Casting

[edit]At the suggestion of Polly Platt, Bogdanovich approached eight-year-old Tatum O'Neal to audition for the role, although she had no acting experience. Bogdanovich had worked with Tatum's father Ryan O'Neal on What's Up, Doc?, and decided to cast them as the leads.[6]

Screenplay

[edit]Various changes were made in adapting the book to film. Addie's age was reduced from twelve to nine to accommodate young Tatum, several events from the book were combined for pacing issues, and the last third of the novel, when Moses and Addie graduate to the big leagues as con artists after going into partnership with a fake millionaire, was dropped. The location was also changed from the rural south of the novel–primarily Alabama—to midwestern Kansas and Missouri.[6]

Filming locations

[edit]The film was shot in the small towns of Hays, Kansas; McCracken, Kansas; Wilson, Kansas; Dorrance, Kansas, and St. Joseph, Missouri. Various shooting locations include the Midland Hotel at Wilson, Kansas; the railway depot at Gorham, Kansas; storefronts and buildings on Main Street in White Cloud, Kansas; Hays, Kansas; sites on both sides of the Missouri River; Rulo Bridge; and St. Joseph, Missouri.

Props

[edit]The car Moses is driving when he agrees to take Addie home is a 1930 Ford Model A convertible; the car Moses buys to impress Miss Trixie is a 1936 Ford V8 De Luxe convertible.[7] The whiskey being sold by the bootlegger shown toward the end of the film is Three Feathers blended whiskey, a label introduced by Oldtyme Distilling Corp. in 1882 and still produced up to the 1980s.[8] The bottle of soda pop Addie drinks is from Nehi Soda, by a company founded as Chero-Cola in 1910, in 1925 renamed Nehi Corporation, which became Royal Crown Company and later Dr Pepper/Seven Up, then Dr Pepper Snapple Group.

Title

[edit]Peter Bogdanovich also decided to change the name of the film from Addie Pray. While selecting music for the film, he heard the song "It's Only a Paper Moon" by Billy Rose, Yip Harburg, and Harold Arlen. Seeking advice from his close friend and mentor Orson Welles, Bogdanovich listed Paper Moon as a possible alternative. Welles responded: "That title is so good, you shouldn't even make the picture, you should just release the title!"[6] Bogdanovich added the scene in which Addie has her picture taken in a paper moon solely so the studio would allow him to use the title.[9]

Cinematography and editing

[edit]Director of photography László Kovács used a red filter on the camera on Orson Welles's advice. Bogdanovich also used deep focus cinematography and extended takes in the film.[6]

Release

[edit]The film was released on April 9, 1973, in Hollywood and May 9 in the United States.

Home media

[edit]The film released on VHS in 1980, re-released 1984, and re-released again in 1995. The LaserDisc released on 1982 and Director Series on May 7, 1995. The DVD released on August 12, 2003. The Criterion Collection released the film on 4K and Blu-ray on November 26, 2024.[10]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film earned an estimated $13 million in North American theater rentals in 1973 (equivalent to $89 million in 2023).[11]

Critical response

[edit]Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised "two first-class performances" from Ryan and Tatum O'Neal but found the film "oddly depressing" and unable to "make up its mind whether it wants to be an instant antique or a comment on one".[12] Roger Ebert gave the film his top four-star rating and commented that "a genre movie about a con man and a little girl is teamed up with the real poverty and desperation of Kansas and Missouri, circa 1936. You wouldn't think the two approaches would fit together, somehow, but, they do, and the movie comes off as more honest and affecting than if Bogdanovich had simply paid tribute to older styles".[13] Gene Siskel gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote that Tatum O'Neal "is more than cute. Her role is something special in the well-established tradition of children on film."[14]

Arthur D. Murphy in Variety called Tatum O'Neal "outstanding" and added, "Alvin Sargent's screenplay is a major contributor to the overall excellent results".[15] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Tatum O'Neal was "just plain marvelous and Paper Moon is a tough, funny, beautifully calculated diversion".[16] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote that the film "may prove a keen disappointment if you go with high expectations. At its best the film is only mildly amusing, and I'm not sure I could come up with a few undeniable highlights if pressed on the point".[17] Tom Milne in The Monthly Film Bulletin called the film "very easy to take, especially as Alvin Sargent's dialogue has a nice edge of wit. The trouble is that the film covers all the ground it is going to cover in the scene in the restaurant near the beginning when we, with Ryan O'Neal, first realise that the sweetly awful child is going to be more than a match for him as far as wits are concerned".[18]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 90% based on 48 reviews, with an average rating of 8.7/10. The site's critics consensus reads, "Expertly balancing tones, Paper Moon is a deft blend of film nostalgia and finely tuned performances – especially from Tatum O'Neal, who won an Oscar for her debut."[19] Metacritic assigned a weighted average score of 77 out of 100 based on eight critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[20]

Awards and nominations

[edit]

At the Academy Awards, Tatum O'Neal won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, making her the youngest competitive Academy Award winner as of 2023[update] (at age 10).[21]

Other media

[edit]In September 1974, a television series called Paper Moon, based on the film, premiered on the ABC television network, with Jodie Foster cast as Addie and Christopher Connelly (who had appeared as O'Neal's brother in the earlier ABC series, Peyton Place) playing Moses. It was not a ratings success, and its thirteenth and last new episode aired in December 1974.[22][23][24]

A stage musical adapted from the film and Addie Pray was produced at the Paper Mill Playhouse in 1993. The show featured a book by Martin Casella, music by Larry Grossman, and lyrics by Ellen Fitzhugh and Carol Hall, and was directed by Matt Casella. The cast included Gregory Harrison, Christine Ebersole, Brooks Ashmanskas, and Christopher Sieber.[25][26]

In The Simpsons episode "The Great Money Caper", Homer and Bart conduct a series of cons, initially to pay to repair the family car. Their attempt to con Ned Flanders by claiming delivery of a personalised Bible ordered by his late wife Maude and requesting reimbursement unravels when Ned realises the con's similarity to that in the film Paper Moon, at which point Homer and Bart bolt.

Legacy

[edit]The head writer of the television series Obi-Wan Kenobi, Joby Harold, looked at the films Paper Moon and Midnight Run as influences for Obi-Wan Kenobi and Leia Organa's relationship after the latter's rescue. Director David Fincher named "Paper Moon" as one of his favorite films and the film that had impact on his career. [27]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tied with Barbra Streisand for The Way We Were.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Terry, Clifford (January 7, 1973). "Bogdanovich in the Flat Lands". Chicago Tribune Magazine. p. I39. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Paper Moon, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2012.

- ^ Klemesrud, Judy (May 16, 1973). "How an Overweight 15‐Year‐Old Found Happiness on a Movie Set". The New York Times.

- ^ "Rose-Mary Rumbley". IMDb. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Stafford, Jeff (October 2006). Paper Moon Archived December 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Turner Classic Movies. Accessed April 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Bogdonavitch, Peter (1973). Paper Moon (Special Features) (DVD). Paramount Pictures.

- ^ "Paper Moon, 1973". Internet Movie Cars Database. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "LIQUOR: The Schenley Reserves". Time. September 29, 1952. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ WTF Podcast Episode 632, August 27, 2015.

- ^ "Paper Moon (1973)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved August 24, 2024.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973". Variety. January 9, 1974. p 19.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (May 17, 1973). "Bogdanovich's 'Paper Moon' at Coronet". The New York Times. p. 53.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 15, 1973). "Paper Moon". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2018 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (June 15, 1973). "He's just mad about Addie". Archived October 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 1.

- ^ Murphy, Arthur D. (April 18, 1973). "Paper Moon". Variety. p. 22.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (June 13, 1973). "'Paper Moon'—Real Star". Los Angeles Times. p. D1.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (June 15, 1973). "A Hollow 'Paper Moon'". The Washington Post. B1.

- ^ Milne, Tom (January 1974). "Paper Moon". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 41 (480): 13.

- ^ "Paper Moon (1973)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved January 23, 2024.

- ^ "Paper Moon Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "The 46th Academy Awards (1974) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ McNeil, pp. 540–541.

- ^ Brooks & Marsh, p. 795.

- ^ The Classic TV Archive Paper Moon Accessed 23 October 2022

- ^ Daniels, Robert L. (September 27, 1993). "Paper Moon". Variety. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ Klein, Alvin (September 26, 1993). "THEATER; 'Paper Moon' Changes Its Outlook as a Musical". New York Times. Retrieved December 27, 2023.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (June 3, 2022). "Obi-Wan Kenobi: Darth Vader Was Originally Even More Terrifying". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Brooks, Tim & Marsh, Earle (1995). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network TV Shows: 1946-Present. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-39736-3.

- McNeil, Alex (1996). Total Television. Penguin Books USA, Inc. ISBN 0-14-02-4916-8.

External links

[edit]- 1973 films

- 1970s crime comedy-drama films

- 1970s road comedy-drama films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime comedy-drama films

- American road comedy-drama films

- 1970s English-language films

- Films about con artists

- Films about orphans

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Peter Bogdanovich

- Films featuring a Best Supporting Actress Academy Award–winning performance

- Films produced by Frank Marshall

- Films set in the 1930s

- Films set in Kansas

- Films set in Missouri

- Films shot in Kansas

- Films shot in Missouri

- Films with screenplays by Alvin Sargent

- Great Depression films

- Paramount Pictures films

- 1970s American films

- 1973 comedy-drama films

- English-language crime comedy-drama films

- English-language road comedy-drama films