Potassium nitrate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Potassium Nitrate

| |

| Other names

Saltpetre

Nitrate of potash Vesta powder | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.926 |

| E number | E252 (preservatives) |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1486 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

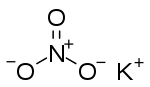

| KNO3 | |

| Molar mass | 101.1032 g/mol |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 2.109 g/cm3 (16 °C) |

| Melting point | 334 °C |

| Boiling point | 400 °C decomp. |

| 133 g/L (0 °C) 383 g/L (25 °C) 2470 g/L (100 °C) | |

| Solubility | slightly soluble in ethanol soluble in glycerol, ammonia |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~7 |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.5056 |

| Structure | |

| Orthorhombic, Aragonite | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Oxidant, Harmful if swallowed, Inhaled, or absorbed on skin. Causes Irritation to Skin and Eye area. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

3750 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Potassium nitrite |

Other cations

|

Lithium nitrate Sodium nitrate Rubidium nitrate Caesium nitrate |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Potassium nitrate (data page) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the formula KNO3. It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and nitrate ions NO3−.

It occurs as a mineral niter and is a natural solid source of nitrogen. Potassium nitrate is one of several nitrogen-containing compounds collectively referred to as saltpeter.

Major uses of potassium nitrate are in fertilizers, food additive, rocket propellants and fireworks; it is one of the constituents of gunpowder.

History of production

The earliest known complete purification process for potassium nitrate was outlined in 1270 by the chemist and engineer Hasan al-Rammah of Syria in his book al-Furusiyya wa al-Manasib al-Harbiyya ('The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices'). In this book, al-Rammah describes first the purification of barud (crude saltpetre mineral) by boiling it with minimal water and using only the hot solution, then the use of potassium carbonate (in the form of wood ashes) to remove calcium and magnesium by precipation of their carbonates from this solution, leaving a solution of purified potassium nitrate, which could then be dried.[2] This was used for the manufacture of gunpowder and explosive devices. The terminology used by al-Rammah indicated a Chinese origin for the gunpowder weapons about which he wrote.[3] While potassium nitrate was called "Chinese snow" by Arabs, it was called "Chinese salt" by the Iranians/Persians.[4][5][6][7][8]

Into the 19th century, niter-beds were prepared by mixing manure with either mortar or wood ashes, common earth and organic materials such as straw to give porosity to a compost pile typically 1.5×2×5 meters in size.[9] The heap was usually under a cover from the rain, kept moist with urine, turned often to accelerate the decomposition, then finally leached with water after approximately one year, to remove the soluble calcium nitrate. Dung-heaps were a particularly common source: they contain ammonia from the decomposition of urea and other nitrogenous materials. It then undergoes bacterial oxidation (first by means of the Nitrosomonas bacteria) to produce (calcium) nitrite, and then (by means of the Spirobacter bacteria) to produce (calcium) nitrate. It is then converted to potassium nitrate by filtering through the potash of wood ashes.

A variation on this process, using only urine, straw and wood ash, is described by LeConte in 1862. Stale urine is placed in a container of straw and is allowed to "sour" (bacterially ferment) for many months, after which water is used to wash the resulting chemical salts from the straw. The process is completed by filtering the liquid through wood ashes, then air-drying in the sun.[9] The nitrate source in this process is calcium nitrate produced by bacterial action on the nitrogenous urea and ammonia from urine, combined with calcium from urine. This calcium nitrate salt is converted again in the standard way to soluble potassium nitrate, using potassium carbonate from potash.

During this period, the major natural sources of potassium nitrate were the deposits crystallizing from cave walls and the accumulations of bat guano in caves. Traditionally, guano was the source used in Laos for the manufacture of gunpowder for Bang Fai rockets.

Potassium nitrates supplied the oxidant and much of the energy for gunpowder in the 19th century, but after 1889, small arms and large artillery increasingly began to depend on cordite, a smokeless powder which required in manufacture large quantities of nitric acid derived from mineral nitrates (either potassium nitrate, or increasingly sodium nitrate), and the basic industrial chemical sulfuric acid. These propellants, like all nitrated explosives (nitroglycerine, TNT, etc.) use the energy available when organic nitrates burn or explode and are converted to nitrogen gas, a process that releases large amounts of energy.

From 1903 until the World War I era, potassium nitrate for black powder and fertilizer was produced on an industrial scale from nitric acid produced via the Birkeland–Eyde process, which used an electric arc to oxidize nitrogen from the air. During World War I the newly industrialized Haber process (1913) was combined with the Ostwald process after 1915, allowing Germany to produce nitric acid for the war after being cut off from its supplies of mineral sodium nitrates from Chile (see nitratite). The Haber process catalyzes ammonia production from atmospheric nitrogen, and industrially produced hydrogen. From the end of World War I until today, practically all organic nitrates have been produced from nitric acid from the oxidation of ammonia in this way. Some sodium nitrate is still mined industrially. Almost all potassium nitrate, now used only as a fine chemical, is produced from basic potassium salts and nitric acid.

Production

Potassium nitrate can be made by combining ammonium nitrate and potassium hydroxide.

- NH4NO3 (aq) + KOH (aq) → NH3 (g) + KNO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

An alternative way of producing potassium nitrate without a by-product of ammonia is to combine ammonium nitrate and potassium chloride, easily obtained as a sodium-free salt substitute.

- NH4NO3 (aq) + KCl (aq) → NH4Cl (aq) + KNO3 (aq)

Potassium nitrate can also be produced by neutralizing nitric acid with potassium hydroxide. This reaction is highly exothermic.

- KOH (aq) + HNO3 → KNO3 (aq) + H2O (l)

Properties

Potassium nitrate has an orthorhombic crystal structure at room temperature, which transforms to a trigonal system at 129 °C. Upon heating to temperatures above 560 °C, it decomposes into potassium nitrite, generating oxygen:

- 2 KNO3 → 2 KNO2 + O2

Potassium nitrate is moderately soluble in water, but its solubility increases with temperature (see infobox). The aqueous solution is almost neutral, exhibiting pH 6.2 at 14 °C for a 10% solution of commercial powder. It is not very hygroscopic, absorbing about 0.03% water in 80% relative humidity over 50 days. It is insoluble in alcohol and is not poisonous; it can react explosively with reducing agents, but it is not explosive on its own.[10]

Uses

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Potassium nitrate has a wide variety of uses, largely as a source of nitrate.

Fertilizer

Potassium nitrate is mainly used in fertilizers, as a source of nitrogen and potassium – two of the macronutrients for plants. When used by itself, it has an NPK rating of 13-0-44.

Oxidizer

Potassium nitrate is an efficient oxidizer, producing a lilac-colored flame upon burning due to the presence of potassium. It is one of the three components of black powder, along with powdered charcoal (substantially carbon) and sulfur, both of which act as fuels in this composition.[11] As such it is used in black powder rocket motors, but also in combination with other fuels like sugars in "rocket candy". It is also used in fireworks such as smoke bombs, made with a mixture of sucrose and potassium nitrate.[12] It is also added to pre-rolled cigarettes to maintain an even burn of the tobacco[13] and is used to ensure complete combustion of paper cartridges for cap and ball revolvers.[14]

Food preservation

In the process of food preservation, potassium nitrate has been a common ingredient of salted meat since the Middle Ages,[15] but its use has been mostly discontinued due to inconsistent results compared to more modern nitrate and nitrite compounds. Even so, saltpeter is still used in some food applications, such as charcuterie and the brine used to make corned beef.[16] Sodium nitrate (and nitrite) have mostly supplanted potassium nitrate's culinary usage, as they are more reliable in preventing bacterial infection than saltpetre. All three give cured salami and corned beef their characteristic pink hue. When used as a food additive in the European Union,[17] the compound is referred to as E252; it is also approved for use as a food additive in the USA[18] and Australia and New Zealand[19] (where it is listed under its INS number 252).

Other uses

- as the main solid particle component of condensed aerosol fire suppression systems. When burned with the free radicals of a fire's flame, it produces potassium carbonate.

- as the main component (usually about 98%) of some tree stump remover products. It accelerates the natural decomposition of the stump by supplying nitrogen for the fungi attacking the wood of the stump.[20]

- for the heat treatment of metals as a solvent in the post-wash. The oxidizing, water solubility and low cost make it an ideal short-term rust inhibitor.

- also used as mango flower inducer in the Philippines.

- as a thermal storage medium. Sodium and potassium nitrate salts are stored in molten state with the solar energy collected by the heliostats at the GEMASOLAR Thermosolar Plant in Spain. Ternary salts, with the addition of calcium nitrate or lithium nitrate, improve the heat storage capacity in the molten salts[21]

Pharmacology

- Used in some toothpastes for sensitive teeth.[22] Recently, the use of potassium nitrate in toothpastes for treating sensitive teeth has increased and it may be an effective treatment.[23][24]

- Used in some toothpastes to relieve asthma symptoms. [citation needed]

- Used historically to treat asthma as well as arthritis.[citation needed]

- Combats high blood pressure and was once used as a hypotensive.

Potassium nitrate was once thought to induce impotence, and is still falsely rumored to be in institutional food (such as military fare) as an anaphrodisiac; however, there is no scientific evidence for such properties.[25][26]

See also

References

- ^ Record of Potassium nitrate in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 2007-03-09.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources, History of Science and Technology in Islam.

- ^ Jack Kelly (27 April 2005). Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-465-03722-3. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter ("Chinese snow") from the East, perhaps through India. They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows"). Arab warriors had acquired fire lances by 1280. Around that same year, a Syrian named Hasan al-Rammah wrote a book that, as he put it, "treat of machines of fire to be used for amusement of for useful purposes." He talked of rockets, fireworks, fire lances, and other incendiaries, using terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources. He gave instructions for the purification of saltpeter and recipes for making different types of gunpowder.

- ^ Peter Watson (26 September 2006). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud. HarperCollins. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-06-093564-1. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

The first use of a metal tube in this context was made around 1280 in the wars between the Song and the Mongols, where a new term, chong, was invented to describe the new horror...Like paper, it reached the West via the Muslims, in this case the writings of the Andalusian botanist Ibn al-Baytar, who died in Damascus in 1248. The Arabic term for saltpetre is 'Chinese snow' while the Persian usage is 'Chinese salt'.28

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan (2006). The age of wars of religion, 1000–1650: an encyclopedia of global warfare and civilization. Vol. Volume 1 of Greenwood encyclopedias of modern world wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 365. ISBN 0-313-33733-0. Retrieved 2011 November 28.

In either case, there is linguistic evidence of Chinese origins of the technology: in Damascus, Arabs called the saltpeter used in making gunpowder " Chinese snow," while in Iran it was called "Chinese salt." Whatever the migratory route

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1970). Artillery: its origin, heyday, and decline. Archon Books. p. 123. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

- ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1963). English artillery, 1326–1716: being the history of artillery in this country prior to the formation of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Royal Artillery Institution. p. 42. Retrieved 2011 November 28.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese Snow and employed it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Oliver Frederick Gillilan Hogg (1993). Clubs to cannon: warfare and weapons before the introduction of gunpowder (reprint ed.). Barnes & Noble Books. p. 216. ISBN 1-56619-364-8. Retrieved 2011 November 28.

The Chinese were certainly acquainted with saltpetre, the essential ingredient of gunpowder. They called it Chinese snow and used it early in the Christian era in the manufacture of fireworks and rockets.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ a b LeConte, Joseph (1862). Instructions for the Manufacture of Saltpeter. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Military Department. p. 14. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|printer=ignored (help) - ^ B. J. Kosanke, B. Sturman, K. Kosanke, I. von Maltitz, T. Shimizu, M. A. Wilson, N. Kubota, C. Jennings-White, D. Chapman (2004). "2". Pyrotechnic Chemistry. Journal of Pyrotechnics. pp. 5–6. ISBN 1-889526-15-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jai Prakash Agrawal (2010). High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics. Wiley-VCH. p. 69. ISBN 978-3-527-32610-5.

- ^ Amthyst Galleries, Inc. Galleries.com. Retrieved on 2012-03-07.

- ^ Inorganic Additives for the Improvement of Tobacco, TobaccoDocuments.org

- ^ Kirst, W.J. (1983). Self Consuming Paper Cartridges for the Percussion Revolver. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Northwest Development Co.

- ^ "Meat Science", University of Wisconsin

- ^ Corned Beef, Food Network

- ^ UK Food Standards Agency: "Current EU approved additives and their E Numbers". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ US Food and Drug Administration: "Listing of Food Additives Status Part II". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code"Standard 1.2.4 – Labelling of ingredients". Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Roark, Stan. "Stump Removal for Homeowners". Alabama Cooperative Extension System. Retrieved 2011-09-26.

- ^ Gemasolar, The First Tower Thermosolar Commercial Plant With Molten Salt Storage System. (PDF) . Retrieved on 2012-03-07.

- ^ "Sensodyne Toothpaste for Sensitive Teeth". 2008-08-03. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ^ "The Effect of Potassium Nitrate and Silica Dentifrice in the Surface of Dentin". Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ Managing dentin hypersensitivity, Robin Orchardson and David G. Gillam, J Am Dent Assoc, Vol 137, No 7, 990–998. 2006

- ^ "The Straight Dope: Does saltpeter suppress male ardor?". 1989-06-16. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Jones, Richard E. (2006). Human Reproductive Biology, Third Edition. Elsevier/Academic Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-12-088465-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Dennis W. Barnum. (2003). "Some History of Nitrates." Journal of Chemical Education. v. 80, p. 1393-. link.

- Alan Williams. "The production of saltpeter in the Middle Ages", Ambix, 22 (1975), pp. 125–33. Maney Publishing, ISSN 0002-6980.