The Great Train Robbery (1903 film)

| The Great Train Robbery | |

|---|---|

Cover of a promotional leaflet for the film | |

| Directed by | Edwin S. Porter |

| Based on | The Great Train Robbery by Scott Marble |

| Starring | Justus D. Barnes G. M. Anderson Walter Cameron |

| Cinematography | Edwin S. Porter J. Blair Smith |

| Distributed by | Edison Manufacturing Company |

Release date |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | Silent |

The Great Train Robbery is a 1903 American silent Western film made by Edwin S. Porter for the Edison Manufacturing Company. It follows a gang of outlaws who hold up and rob a steam locomotive at a station in the American West, flee across mountainous terrain, and are finally defeated by a posse of locals. The short film draws on many sources, including a robust existing tradition of Western films, recent European innovations in film technique, the play of the same name by Scott Marble, the popularity of train-themed films, and possibly real-life incidents involving outlaws such as Butch Cassidy.

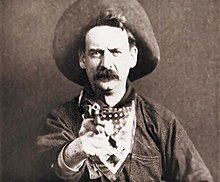

Porter produced (i.e. supervised; the job title "film director" had not yet been developed) and photographed the film in New York and New Jersey in November 1903; the Edison studio began selling it to vaudeville houses and other venues in the following month. The cast included Justus D. Barnes and G. M. Anderson, who may have also helped with planning and staging. Porter's storytelling approach, though not particularly innovative or unusual for 1903, allowed him to include many popular techniques of the time, including scenes staged in wide shots, a matte effect, and an attempt to indicate simultaneous action across multiple scenes. Camera pans, location shooting, and moments of violent action helped give the film a sense of rough-edged immediacy. A special close-up shot, which was unconnected to the story and could either begin or end the film depending on the projectionist's whim, showed Barnes, as the outlaw leader, emptying his gun directly into the camera.

Due in part to its popular and accessible subject matter, as well as to its dynamic action and violence, the film was an unprecedented commercial success. Though it did not significantly influence or advance the Western film genre, it was widely distributed and copied, including in a parody by Porter himself. During the twentieth century, inaccurate legends about the film developed, claiming it was the first Western or even the first film to tell a story; though film scholars have repeatedly disproved these claims, demonstrating that the film was a stylistic dead-end for its maker and genre, the film's commercial success and mythic place in American film lore remain undisputed. The film, especially the close-up of Barnes, has become iconic in American culture, appearing in numerous film and television references and homages.

Plot

Two bandits break into a railroad telegraph office, where they force the operator at gunpoint to have a train stopped and to transmit orders for the engineer to fill the locomotive's tender at the station's water tank. They then knock the operator out and tie him up. As the train stops it is boarded by the bandits—now four. Two bandits enter an express car, kill a messenger, and open a box of valuables with dynamite.

In a fight on the engine car, the others kill the fireman and force the engineer to halt the train and disconnect the locomotive. The bandits then force the passengers off the train and rifle them for their belongings. One passenger tries to escape but is instantly shot down. Carrying their loot, the bandits escape in the locomotive, later stopping in a valley where their horses had been left.

Meanwhile, back in the telegraph office, the bound operator awakens but collapses again. His daughter arrives, bringing him his meal, and cutting him free when she discovers him bound; she restores him to consciousness by dousing him with water.

There is some comic relief at a dance hall, where an Eastern stranger (a "tenderfoot") is forced to dance while the locals fire at his feet. The door suddenly opens and the telegraph operator rushes in to tell them of the robbery. The men quickly form a posse, which chases the bandits through the mountains. The posse finally overtakes the bandits, and in a final shootout kills them all and recovers the stolen mail.

A standalone final scene, separate from the narrative, presents a medium close-up of the leader of the outlaws, who empties his pistol point-blank directly into the camera.

-

1. Interior of Railroad Telegraph Office

-

2. At the Railroad Water Tank

-

3. Interior of Express Car

-

4. The Fight on the Tender

-

5. The Train Uncoupled

-

6. The Exterior of Passenger Coaches

-

7. The Escape

-

8. Off to the Mountains

-

9. A Beautiful Scene in a Valley

-

10. Interior of Telegraph Office

-

11. Interior of a Dance Hall

-

12. The Posse in Pursuit

-

13. The Battle to the Death

-

14. Realism

Background

In the years leading up to The Great Train Robbery, the film industry was marked by much innovation and variety. Some studios, such as the Edison Manufacturing Company and the Lumière company, were best known for short sketches and actuality films presented in a straightforward style,[2] often only a single shot long.[3] However, many other filmmakers aimed for more elaborate productions. Georges Méliès's films, such as the 1902 international success A Trip to the Moon, became acclaimed for their visual storytelling, often encompassing multiple scenes and involving careful editing and complicated special effects. Meanwhile, English filmmakers working in and around Brighton, a group later nicknamed the "Brighton School", made many innovations in narrative film grammar, developing framing and cutting conventions that would later become industry standards.[4]

Edwin S. Porter had won acclaim making cameras, film printers, and projectors; however, after his workshop was destroyed by a fire, he accepted a special commission for the Edison Manufacturing Company in 1901. His task to improve Edison's existing projecting equipment was a marked success, and Porter was given a regular job as the cameraman for Edison's New York film studio.[5] (At this point in the American film industry, this job title included operating the camera as well as exercising the creative control that would later be called film directing.)[6]

His early films were sketches and actualities in the simple style used by other Edison employees.[2] However, his job also gave him the chance to view the many foreign films the Edison company were distributing and pirating,[6] and around 1901 or 1902 he discovered the more complex films being made by Méliès and the Brighton School. He began attempts to bring Edison films to a similar level of achievement,[2] later recalling:

From laboratory examination of some of the popular films of the French pioneer director, Georges Méliès—trick films like A Trip to the Moon—I came to the conclusion that a picture telling a story might draw the customers back to the theatres, and set to work in this direction.[7]

The Edison studio, facing growing competition from other American companies, welcomed Porter's ambitious plans.[6] His first major attempts at elaborate storytelling films included a 1902 adaptation of Jack and the Beanstalk in imitation of Méliès, and a 1903 Life of an American Fireman in the style of a notable Brighton School film, Fire![8] His films did well and were influential, bolstered by his status as the leading filmmaker at the most important American studio.[6]

In October 1903, Porter joined forces with a new Edison hire, Max Aronson, a young stage actor billed under the name G. M. Anderson. His initial jobs for the studio were inventing sight gags and playing occasional roles, but he was soon working with Porter on creative collaborations.[9] Porter's next major film was The Great Train Robbery; Porter was in charge of production and photography, while Anderson may have assisted on staging.[10]

Sources

Porter (and possibly Anderson) drew on various sources when planning the scenario for The Great Train Robbery.[11] Western themes were already popular in films and other entertainment, reflecting the wide public interest in stories about the past and present of the American West. Many American films before 1900 can be classified as Westerns,[12] such as actuality views of cowboy life, staged Western anecdotes like A Bluff from a Tenderfoot and Cripple Creek Bar-Room Scene (both 1899), and shots of Annie Oakley and of Oglala and Brulé dancers from Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show (both 1894).[13]

Studios abroad also began telling Western stories early on, with Mitchell and Kenyon's 1899 British film Kidnapping by Indians the first known example.[14] Edison's 1901 film Stage Coach Hold-up, based on Buffalo Bill's "Hold-up of the Deadwood Stage" act, probably influenced Porter directly.[11] Porter may have also been inspired by recent real events related to the American West: in August 1900, Butch Cassidy and his gang had robbed a Union Pacific Railroad train and escaped capture,[15] and in September 1903, Bill Miner's gang made an unsuccessful holdup of an Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company train.[16]

For the film's title and basic concept, Porter looked to Scott Marble's The Great Train Robbery, a popular stage melodrama that had premiered in Chicago in 1896 and had been revived in New York in 1902. The play covers the adventures of a Texas criminal gang who attempt to steal a $50,000 gold shipment from a Wells Fargo office in Missouri. Their initial scheme is for a mole planted in the company to make off with the gold before it leaves Missouri by train; this plan goes awry, and only leads to an innocent man's arrest. However, using information received at a Texas mountain saloon, the gang are still able to stop the train, blast open the car containing the gold, and bring it back to their secret hideout in a Red River canyon. The United States Marshals Service tracks down the gang and finally defeats them in a climactic fight, with cowboys and Native Americans drawn into the fray.[11]

For the narrative style of the film, Porter likely drew freely on various recent popular films, made by other filmmakers experimenting with elaborate storytelling.[11] A Daring Daylight Burglary, a British chase drama from the Sheffield Photo Company, has frequently been cited as particularly influential;[2][17] it and another British film, Desperate Poaching Affray, were successfully imported to America and started a decade-long vogue for films centered on chases.[18] A Daring Daylight Burglary's story and editing appear to have supplied the overall narrative structure for The Great Train Robbery,[17][11] though in the latter film the chase is only made explicit in one shot, the twelfth.[19] Porter's plot also profited from the booming popularity of railroad-related film attractions, such as phantom rides and standalone comic scenes set on trains. The Great Train Robbery would treat the rail theme more elaborately than was common, showing its train from various angles and involving it in a dramatic adventure.[20]

Filming

Porter filmed The Great Train Robbery in November 1903. Some scenes were photographed at the Edison studio in New York, and others were done in New Jersey, in Essex County Park and along the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. The stream-crossing scene was filmed at Thistle Mill Ford in the South Mountain Reservation of Essex County Park.[9] The cast included Justus D. Barnes as the leader of the outlaws, Walter Cameron as the sheriff, Porter's colleague Anderson in three small roles (the murdered passenger, the dancing tenderfoot, and one of the robbers), and many Edison workers among the extras.[9] Edison filmmaker J. Blair Smith was one of the camera operators.[9]

According to rumors in a contemporary New York Times piece on the film, the Edison Company initially attempted to get the railroad company to lend their tracks and cars for free, arguing that the film would be good publicity for the line; the railroad directors disagreed, but eventually allowed their resources to be used if Edison also made a more straightforward advertising film for them. The article adds that a real fireman and engineer play those respective parts in the film, and that the filming caused some disturbance when the dummy thrown off the locomotive was mistaken by passersby for a real accident victim.[21]

Porter's filmic style for The Great Train Robbery was not on the cutting edge for 1903; it is comparable to numerous other films released around the same time, such as The Escaped Lunatic, a popular Biograph Studios comedy about wardens chasing an escapee from a mental institution, and Runaway Match, a British Gaumont film featuring an extended car chase sequence.[11] Mary Jane's Mishap, a landmark dark comedy made by Brighton School pioneers G. A. Smith and Laura Bayley and released months before The Great Train Robbery, is far more sophisticated in its editing and framing.[22] Porter's style heavily prioritized action over character, with most figures remaining indistinguishable in wide shots; the staging inconsistently mixes stylized theatrical blocking with more naturalistic action. The film also leaves many narrative points ambiguous, requiring explanations to be filled in by a live narrator or by audience imaginations.[23]

However, the film successfully collected many popular themes and prevalent techniques of the time into a single accessible narrative.[24] Porter cut his shots together to suggest action happening simultaneously in different locations, as he had done in Life of an American Fireman, but more efficiently than in that film.[15] The use of real outdoor locations and violent action helped keep the film dynamic,[15] as did technical strategies such as a matte combining a studio scene with outdoor footage, and three shots in which the camera moves. These three shots add an edge of realism and immediacy, with the frame following the action if recording real life in a documentary style; one of these shots, showing the robbers making off with their loot, even requires the mounted camera to attempt a tricky diagonal pan, creating a jagged effect.[18]

The final shot, in which Barnes fires at the camera in a framing reminiscent of a wanted poster, is the film's only close-up, and does not function as part of the plot.[15] Porter rarely used close-ups, especially in his later years, preferring to save them for special standalone effects like this one.[25] The Edison Manufacturing Company's promotional leaflet about the film describes this scene as follows:

Scene 14—REALISM. A life size picture of Barnes, leader of the outlaw band, taking aim and firing point blank at each individual in the audience. (This effect is gained by foreshortening in making the picture.) The resulting excitement is great. This section of the scene can be used either to begin the subject or to end it, as the operator may choose.[26]

The catalogue's informal approach to where the scene should be placed was not unique to The Great Train Robbery; Porter's adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin, released earlier in 1903, had included a boat race scene that was variously advertised as Scene 5 (where it would make some narrative sense) or as Scene 10 (where it would not).[25] Such shots, designed primarily for spectacle rather than for narrative coherency, characterize a popular early-film style later nicknamed the "cinema of attractions".[15][27]

Release and reception

In 1903, the most common American film venue was vaudeville houses, where films were exhibited as part of a varied bill of entertainment; other informal venues also sometimes showed films.[28] The Edison Manufacturing Company announced the coming film to exhibitors in early November 1903, calling it a "highly sensationalized Headliner". To secure copyright, they submitted a rough cut of the film (about fifteen feet longer than the final cut) to the Library of Congress, where it survives as a paper print.[24]

The final release print was made available in early December 1903.[24] Edison sold it to exhibitors for US$111, as a 740-foot reel.[29] The first known showing of The Great Train Robbery was at a New York City dime museum, Huber's Museum. By the following week it was appearing at eleven venues in the city area, including the Eden Musée, a major amusement center.[24] Edison advertising touted the film as "absolutely the superior of any moving picture ever made" and a "faithful imitation of the genuine 'Hold Ups' made famous by various outlaw bands in the far West".[30]

The Great Train Robbery was a major commercial success for the Edison company.[31] It played as the headlining attraction in many vaudeville houses, and showed up frequently at two other entertainment venues that proliferated across the United States in the following years: immersive venues where the spectator took simulated railroad journeys, such as Hale's Tours of the World,[32] and a new kind of film venue, the nickelodeon, where The Great Train Robbery was often the first attraction shown.[19]

Overall, it may have had the biggest success of any film made before 1905.[33] The film's popularity was helped by its timely subject matter (as train robberies were still a familiar news item)[34] as well as its striking depictions of action and violence.[33] Unusually for the time, the film was even described in detail in the New York Times; the anonymous reviewer criticized most of the players, but praised the horse riding and stunts, concluding: "All this is the result of poor acting, but the results are certainly astounding."[21]

The film was also widely imitated and copied; the Lubin Manufacturing Company made a shot-for-shot remake of it in August 1904, changing only small details.[35][34] (American film copyright was legally murky until the 1912 Townsend Amendment to the Copyright Act of 1909, so despite the film's Library of Congress registration, unauthorized remakes and adaptations could be made with impunity.)[36] Porter himself directed a 1905 parody of the film, The Little Train Robbery, with children robbing candy and dolls from a miniature railroad car.[37]

Despite its wide success and imitators, The Great Train Robbery did not lead to a significant increase in Western-themed films; instead, the genre continued essentially as it had before, in a scattered mix of short actualities and longer stories.[34][38] These, especially the actualities, gradually decreased in vogue, and it was not until 1908 that American Western films began to proliferate in earnest.[38] One of the leading contributors to this later Western film boom was Porter's colleague Anderson, now billed as Broncho Billy Anderson.[34]

Porter continued to make films for more than a decade after, usually in a similar editing style to The Great Train Robbery, with few additional technical innovations. One historian commented that later Porter efforts like The Count of Monte Cristo (1913) were "if anything a retrogression from The Great Train Robbery and had less innate cinema sense."[31] However, Porter's later works continued to be imaginative in content, including The Kleptomaniac, a notable 1905 social justice film.[33]

Several prints of The Great Train Robbery survive; a few of these were heavily edited and altered by their owners, but most are in their release state, and at least one is hand-colored.[24]

Legacy

In the decades after The Great Train Robbery, various inaccurate legends developed, exaggerating its historical significance.[39] By mid-century, mistaken claims that it was the "first Western" or even the "first story film" were common.[31] Critiquing these inaccurate legends and citing the film's actual lack of impact on the Western genre, historian Scott Simmon comments that in fact the film's "main surprise in retrospect is how it led nowhere, either for its creator or the genre, beyond serving loosely as a narrative model for gun-wielding crime and horse-chase retribution."[38] Claims about historical priority continued to be repeated by general-audience writers into the early twenty-first century.[40]

Later film critics, abandoning the exaggerated claims, have tended to explain the film's significance mostly in terms of its wide popularity and Porter's influential action-driven storytelling. William Everson and George Fenin dubbed it "the first dramatically creative American film", while Robert Sklar praised the film's capacity "to unite motion picture spectacle with myth and stories about America that were shared by people throughout the world."[24] Historians have cited The Great Train Robbery as Porter's most important film,[41] and noted it as a popular early film that collects numerous important Western tropes, such as "elements of fisticuffs, horseback pursuit and gunplay".[31] Film historian Pamela Hutchinson highlights especially the iconic close-up scene, "a jolt of terror as disconcerting as a hand bursting from a grave":

It's an especially violent act, both in real terms, and cinematic ones. The narrative momentum of the film is cast aside, then the fourth wall of the screen is broken by his gaze, only to be further ruptured by his bullets. Placed at the opening of the film, it might act as a trailer for the shoot-'em-up action to come. As a coda, it's a warning to the audience that it's a wild world out there, and the violence continues even after the train robber case has been closed.[15]

The Great Train Robbery was added to the United States National Film Registry in 1990.[42] In popular culture, numerous films and television shows have referenced the film and the iconic Barnes close-up:

- Historian James Chapman compares the James Bond gun barrel sequences, conceived by Maurice Binder, to the close-up.[43]

- The Batman episode "The Riddler's False Notion" (1966) guest-stars silent film icon Francis X. Bushman as a film collector who owns a print of The Great Train Robbery.[44]

- The German ZDF series Western von gestern (1978–1986) uses the Barnes close-up for its opening and closing sequences.[45]

- The final scene of Martin Scorsese's Goodfellas (1990), in which Tommy DeVito (portrayed by Joe Pesci) shoots at the camera, recreates the close-up as a homage.[15] Scorsese has commented that the shot is "…a reference to the end of The Great Train Robbery… And the plot of this picture is very similar to The Great Train Robbery."[46]

- The Arthur episode "Francine Frensky, Superstar" (1996) involves a school play featuring a loose reenactment of the film.[47]

- The Breaking Bad episode "Dead Freight" (2012) pays homage to The Great Train Robbery, with a matching final shot.[48]

- The BoJack Horseman episode "Say Anything" (2014) has show-business old-timer Lenny Turteltaub confusing The Great Train Robbery with the famous Lumiere film L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, reminiscing: "As I said to Ed Porter at the premiere of The Great Train Robbery, 'Aggh! The train's coming right at me!'"[49]

See also

References

- ^ Pratt 1973, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b c d Cook 1981, p. 19.

- ^ Thompson & Bordwell 1994, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Thompson & Bordwell 1994, pp. 16–19.

- ^ Musser 1990, pp. 314–315.

- ^ a b c d Thompson & Bordwell 1994, p. 22.

- ^ Cook 1981, p. 20.

- ^ Musser 1990, pp. 325–327.

- ^ a b c d Musser 1991, p. 253.

- ^ Musser 1990, p. 352.

- ^ a b c d e f Musser 1991, p. 256.

- ^ Everson 1969, p. 14.

- ^ Simmon 2009, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Anonymous 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hutchinson 2016.

- ^ Musser 1991, pp. 258–59.

- ^ a b Pratt 1973, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b Musser 1991, p. 259.

- ^ a b Musser 1991, p. 260.

- ^ Musser 1991, p. 261–64.

- ^ a b Anonymous 1904.

- ^ Barnes 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Lusted 2014, p. 74–77.

- ^ a b c d e f Musser 1991, p. 254.

- ^ a b Pratt 1973, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Pratt 1973, p. 36.

- ^ Lusted 2014, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Thompson & Bordwell 1994, p. 20.

- ^ Pratt 1973, pp. 34.

- ^ Smith & Selzer 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Everson 1969, p. 15.

- ^ Musser 1991, p. 264.

- ^ a b c Thompson & Bordwell 1994, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Everson 1969, p. 16.

- ^ Slide 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Evina 2004.

- ^ Musser 1991, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Simmon 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Everson 1969, p. 14–15.

- ^ Lusted 2014, p. 73.

- ^ Thompson & Bordwell 1994, pp. 19.

- ^ Gamarekian 1990.

- ^ Chapman 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Eisner & Krinsky 1984, p. 93.

- ^ ZDF 1978.

- ^ Cousins 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Fallon 1996.

- ^ Vacano 2020, pp. 260–61.

- ^ Lawson 2014.

Works cited

- Anonymous (March 13, 1904), "'The Great Train Robbery,' as Rehearsed in New Jersey", The New York Times, p. SM3

- Anonymous (October 31, 2019), "World's first Western movie 'filmed in Blackburn'", BBC News, British Broadcasting Corporation

- Barnes, John (2004), "Mary Jane's Mishap: An Early British Film Re-examined", Film History, 16 (1): 54–59, JSTOR 3815559

- Chapman, James (2000), Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-12048-6

- Cook, David A. (1981), A History of Narrative Film, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0393013707

- Cousins, Mark (2002), Scene by Scene: Film Actors and Directors Discuss Their Work, London: Laurence King, ISBN 9781856692878

- Eisner, Joel; Krinsky, David (1984), Television Comedy Series: An Episode Guide To 153 TV Sitcoms In Syndication, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, ISBN 0-899-50088-9

- Everson, William K. (1969), A Pictorial History of the Western Film, Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press

- Evina, Frank (October 2004), "Copyright Lore" (PDF), Copyright.gov, United States Copyright Office

- Fallon, Joe (October 18, 1996), "Francine Frensky, Superstar", Arthur, vol. season 1, episode 10b, PBS

- Gamarekian, Barbara (October 19, 1990), "Library of Congress Adds 25 Titles to National Film Registry", The New York Times, retrieved July 22, 2009

- Hutchinson, Pamela (February 2016), "Endings...: The Great Train Robbery", Sight & Sound, British Film Institute, p. 112

- Lawson, Joe (August 22, 2014), "Say Anything", BoJack Horseman, vol. season 1, episode 7, Netflix

- Lusted, David (2014), The Western, London: Routledge

- Musser, Charles (1990), The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- Musser, Charles (1991), Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Company, Berkeley: University of California Press

- Pratt, George C. (1973), Spellbound in Darkness: A History of the Silent Film, Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society

- Simmon, Scott (2009), The Invention of the Western Film: A Cultural History of the Genre's First Half-Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Slide, Anthony (1994), Early American Cinema (rev. ed.), Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, p. 17, ISBN 9780810827226

- Smith, Michael Glover; Selzer, Adam (2015), Flickering Empire: How Chicago Invented the U.S. Film Industry, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-85079-7

- Thompson, Kristin; Bordwell, David (1994), Film History: An Introduction, New York: McGraw-Hill

- Vacano, Koen (2020), "Breaking Bad as Mirror of Medea: A Case for Comparative Reception", in Rijser, David; de Pourcq, Maarten; de Haan, Nathalie (eds.), Framing Classical Reception Studies: Different Perspectives on a Developing Field, Leiden: Brill, pp. 245–271

- ZDF (1978), Western von gestern, ZDF, opening and closing

External links

- The Great Train Robbery at IMDb

- The Great Train Robbery at the TCM Movie Database

- The Great Train Robbery at AllMovie

- The Great Train Robbery at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Great Train Robbery at Filmsite.org

- The Great Train Robbery essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 10-12 [1]

- 1903 films

- 1900s action films

- 1900s Western (genre) films

- American films

- American heist films

- American silent short films

- American Western (genre) action films

- American black-and-white films

- Films about train robbery

- Films about hijackings

- American films based on plays

- Films directed by Edwin S. Porter

- Films set in the 1870s

- Films shot in New Jersey

- Thomas Edison

- Surviving American silent films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Edison Manufacturing Company films

- 1900s crime films