Tim Horton

| Tim Horton | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hockey Hall of Fame, 1977 | |||

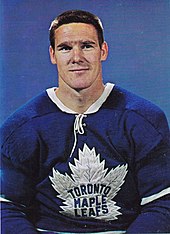

Horton with the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1965 | |||

| Born |

January 12, 1930 Cochrane, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Died |

February 21, 1974 (aged 44) St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada | ||

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm) | ||

| Weight | 180 lb (82 kg; 12 st 12 lb) | ||

| Position | Defence | ||

| Shot | Right | ||

| Played for |

Toronto Maple Leafs New York Rangers Pittsburgh Penguins Buffalo Sabres | ||

| Playing career | 1949–1974 | ||

Miles Gilbert "Tim" Horton (January 12, 1930 – February 21, 1974)[1][2][3] was a Canadian professional ice hockey defenceman who played 24 seasons in the National Hockey League (NHL). He played for the Toronto Maple Leafs, New York Rangers, Pittsburgh Penguins, and Buffalo Sabres. In 2017, Horton was named one of the 100 Greatest NHL Players in history.[4] He died following a single-vehicle crash in 1974 caused by driving while intoxicated at the age of 44.

A successful businessman, Horton was the co-founder of the Tim Hortons restaurant chain.

Early life

Horton was born in Cochrane, Ontario, at Lady Minto Hospital, to Ethel May (née Irish) and Aaron Oakley Horton, a Canadian National Railway mechanic. He had one brother, Gerry Horton.[5]

The family moved in 1935 to Duparquet, Quebec, returning to Ontario in 1938 to Cochrane; the family moved to Sudbury in 1945.[6]

Playing career

Early career

Horton grew up playing ice hockey in Cochrane, and later in a mining community near Timmins. The Toronto Maple Leafs organization signed him in 1948; he moved to Toronto to play junior hockey and attended St. Michael's College School.[citation needed]

Toronto Maple Leafs

Two years later, he turned pro with the Toronto Maple Leafs' farm team, the Pittsburgh Hornets of the American Hockey League. He spent most of the first three seasons with Pittsburgh, playing in his first NHL game on March 26, 1950. Horton appeared in the NHL again in the fall of 1952. He remained a Leaf until 1970, winning four Stanley Cups. Horton later played for the New York Rangers, Pittsburgh Penguins and Buffalo Sabres. He was known for his extreme strength and calmness under pressure. As a hard-working and durable defenceman, he gained relatively few penalty minutes for an enforcer-type defenceman. He was also an effective puck carrier – in 1964–65 he played right wing for the Leafs. Horton appeared in seven National Hockey League All-Star Games. He was named an NHL first team All-Star three times: (1964, 1968, and 1969). He was selected to the NHL Second Team three times: (1954, 1963, 1967).

Between February 11, 1961, and February 4, 1968, Horton appeared in 486 consecutive regular season games; this remains the Leafs club record for consecutive games and was the NHL record for consecutive games by a defenceman until broken by Kārlis Skrastiņš on February 8, 2007.

Horton had a reputation for enveloping players fighting him in a crushing bear hug.

While playing, Horton was generally acknowledged as the strongest man in the game; injuries and age were little more than minor inconveniences. Chicago Black Hawks left wing Bobby Hull declared, "There were defencemen you had to fear because they were vicious and would slam you into the boards from behind, for one, Eddie Shore. But you respected Tim Horton because he didn't need that type of intimidation. He used his tremendous strength and talent to keep you in check."

In 1962, he scored three goals and 13 assists in 12 playoff games, setting a Leafs team record for playoff points by a defenceman. This record was tied in 1978 by Ian Turnbull (who played 13 games), but was not broken until 1994, when David Ellett registered 18 points (albeit in 18 games).

Post-Toronto years

In March 1970, the Maple Leafs traded Horton to the New York Rangers for future considerations; he spent the last fifteen games of the season in New York and all of the following as well. At the beginning of the 1971–72 season, he was claimed by the Pittsburgh Penguins in the intra-league draft and, at age 41, signed a one-year contract for an estimated $100,000, the largest contract at the time for the five-year-old franchise.[7] With a broken ankle and a shoulder separation,[8] Horton only played 44 games for the Penguins and managed just 11 points.

In spite of Horton's age, 42, and considerable nearsightedness, Punch Imlach of the Buffalo Sabres, who was also the former Leafs' general manager, acquired Horton in the Intra-league draft and signed him in 1972.[9][10] In 1973, his performance assisted the Sabres in their first playoff appearance. Horton later signed a contract extension in the off-season.[11]

While playing for the Leafs, Horton wore the number 7, the same number worn by King Clancy from 1930 to 1937. The team declared both Horton and Clancy honoured players at a ceremony on November 21, 1995, but did not retire the number 7 from team use; despite this, it became an honoured jersey number,[12][13] abiding by Leafs honours policy.[14] In 2016, the Leafs changed their retirement policy and, on October 15, retired the number 7 in honour of both Horton and Clancy.[15]

Horton wore number 2 in Buffalo (as Rick Martin already had the number 7). Both numbers have since been retired.[16]

Career statistics

Regular season and playoffs

| Regular season | Playoffs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Team | League | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | GP | G | A | Pts | PIM | ||

| 1946–47 | Copper Cliff Jr. Redmen | NOHA | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1947–48 | St. Michael's Majors | OHA | 32 | 6 | 7 | 13 | 137 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1948–49 | St. Michael's Majors | OHA | 32 | 9 | 18 | 27 | 95 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1949–50 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 1949–50 | Pittsburgh Hornets | AHL | 60 | 5 | 18 | 23 | 83 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1950–51 | Pittsburgh Hornets | AHL | 68 | 8 | 26 | 34 | 129 | 13 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 16 | ||

| 1951–52 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1951–52 | Pittsburgh Hornets | AHL | 64 | 12 | 19 | 31 | 146 | 11 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 16 | ||

| 1952–53 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 2 | 14 | 16 | 85 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1953–54 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 7 | 24 | 31 | 94 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 1954–55 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 67 | 5 | 9 | 14 | 84 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1955–56 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 35 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 36 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | ||

| 1956–57 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 66 | 6 | 19 | 25 | 72 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1957–58 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 53 | 6 | 20 | 26 | 39 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1958–59 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 5 | 21 | 26 | 76 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 16 | ||

| 1959–60 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 3 | 29 | 32 | 69 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 1960–61 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 57 | 6 | 15 | 21 | 75 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 1961–62 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 10 | 28 | 38 | 88 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 16 | 16 | ||

| 1962–63 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 6 | 19 | 25 | 69 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 10 | ||

| 1963–64 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 9 | 20 | 29 | 71 | 14 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 20 | ||

| 1964–65 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 12 | 16 | 28 | 95 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13 | ||

| 1965–66 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 6 | 22 | 28 | 76 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 12 | ||

| 1966–67 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 70 | 8 | 17 | 25 | 70 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 25 | ||

| 1967–68 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 69 | 4 | 23 | 27 | 82 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1968–69 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 74 | 11 | 29 | 40 | 107 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | ||

| 1969–70 | Toronto Maple Leafs | NHL | 59 | 3 | 19 | 22 | 91 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| 1969–70 | New York Rangers | NHL | 15 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 28 | ||

| 1970–71 | New York Rangers | NHL | 78 | 2 | 18 | 20 | 57 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 14 | ||

| 1971–72 | Pittsburgh Penguins | NHL | 44 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 40 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| 1972–73 | Buffalo Sabres | NHL | 69 | 1 | 16 | 17 | 56 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 1973–74 | Buffalo Sabres | NHL | 55 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 53 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| NHL totals | 1,446 | 115 | 403 | 518 | 1,611 | 126 | 11 | 39 | 50 | 183 | ||||

Doughnut industries

In 1964, Horton opened his first Tim Horton Doughnut Shop in Hamilton, Ontario on Ottawa Street.[17] He added a few of his culinary creations to the initial menu. By 1968, Tim Horton had become a multi-million dollar franchise system.[citation needed] Horton's previous business ventures included both a hamburger restaurant and Studebaker auto dealership in Toronto.[citation needed]

Upon Horton's death in 1974, his business partner Ron Joyce bought out the Horton family's shares for $1 million and took over as sole owner of the existing chain, which had 40 stores at the time,[18] and later expanded to nearly 4,600 stores in Canada alone by 2013. Today, Tim Hortons is a flagship of Restaurant Brands International, a conglomerate that includes Burger King and Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen. Restaurant Brands International is majority-owned by Brazilian investment firm 3G Capital.

Joyce's son, Ron Joyce Jr., is married to Horton's eldest daughter, Jeri-Lynn Horton-Joyce; the couple own Tim Hortons franchises in Cobourg, Ontario.[19]

Death and aftermath

Horton was killed after losing control of his De Tomaso Pantera sports car on the Queen Elizabeth Way in St. Catharines, Ontario, in the early morning of February 21, 1974.[1][20] He had played a game in Toronto the previous evening against his former team, the Maple Leafs, and was driving alone back to Buffalo, 100 mi (160 km) south. The Sabres had lost the game, and despite sitting out the third period and playing with a jaw and ankle injury, Horton was selected one of the game's three stars.[2][21]

Horton's Pantera had been given to him by Sabres' general manager Imlach as an enticement to return to the team for one more season.[22]

On his drive to Buffalo, Horton stopped at his office in Oakville, and was met there by Ron Joyce.[22][23] While there, Horton phoned his brother Gerry, who recognized that Tim had been drinking and tried to persuade him not to continue driving. Joyce also offered to have Horton stay with him. Horton chose to continue his drive to Buffalo.[23]

After 4:00 a.m. EST (9:00 UTC), a woman reported to the Ontario Provincial Police in Burlington that she had observed a car travelling at high speed on the Queen Elizabeth Way. A warning was broadcast over police radio. Thirty minutes later, Constable Mike Gula observed a speeding vehicle travelling Niagara-bound on the Queen Elizabeth Way in Vineland. Gula activated his emergency lights and siren and attempted to pursue Horton's vehicle, but lost sight of it.[23][24]

Horton passed a curve in the road at Ontario Street and was approaching the Lake Street exit in St. Catharines when he lost control and drove into the centre grass median, where his tire caught a recessed sewer which caused the car to flip several times before it came to a stop on its roof in the Toronto-bound lanes. Not wearing a seatbelt, Horton was found 123 ft (37 m) from the car.[1] He was pronounced dead at St. Catharines General Hospital.[20][24]

Subsequent to Horton's death, there was no official public inquiry, and his autopsy was not made public. Police would not state whether Horton was intoxicated.[25] In 2005, Horton's autopsy was made public (with witness statements redacted), and revealed that Horton's blood alcohol level was twice the legal limit, and that a half-filled vodka bottle was amongst the crash debris. Horton was also in possession of the drugs Dexedrine, a stimulant, and Dexamyl, a stimulant-sedative; traces of amobarbital, an ingredient in Dexamyl, were found in his blood. The autopsy report found no painkillers in Horton's body, and also concluded that his car had been in good working order. There was nothing to suggest Horton was evading police, or that police were near enough to initiate a criminal pursuit.[20][25] Horton was interred at York Cemetery, Toronto.[26]

Married in 1952, he was survived by his wife, the former Lori Michalek of Pittsburgh, and four daughters.[2][3][27]

Following Horton's death, Ron Joyce offered Horton's widow Lori $1 million for her shares in the chain, which included 40 stores. She accepted his offer and Joyce became sole owner. Years later, Lori became dissatisfied with Joyce's offer, and filed a lawsuit against him. In 1993, Lori lost the lawsuit; an appeal was declined in 1995. She died in 2000 at age 68.[28]

Awards and achievements

- Named to NHL first All-Star team in 1964, 1968, and 1969

- Named to NHL second All-Star team in 1954, 1963, and 1967

- 1961–62 – Stanley Cup champion

- 1962–63 – Stanley Cup champion

- 1963–64 – Stanley Cup champion

- 1966–67 – Stanley Cup champion

- 1977 – inducted (posthumously) into the Hockey Hall of Fame

- 1982 – inducted (posthumously) into the Buffalo Sabres Hall of Fame[29]

- 1996 – number 2 jersey retired by the Buffalo Sabres

- 1998 – ranked number 43 on The Hockey News list of the 100 Greatest Hockey Players

- 2004 – ranked number 59 in The Greatest Canadian list by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- 2015 – recipient of the Bruce Prentice Legacy Award by the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame[30]

- 2016 – number 7 jersey retired by the Toronto Maple Leafs[31]

- In January 2017, Horton was part of the first group of players to be named one of the "100 Greatest NHL Players in history" by the league.[4]

See also

- List of ice hockey players who died during their playing career

- List of NHL players with 1000 games played

References

- ^ a b c "Horton's death shocks hockey world;". The Gazette. Montreal. The Canadian Press. February 22, 1974. p. 30.

- ^ a b c "Hockey World Mourning Death of Tim Horton". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. February 22, 1974. p. B2.

- ^ a b "Horton killed in crash; ex-mates here saddened". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 22, 1974. p. 11.

- ^ a b "100 Greatest NHL Players". National Hockey League. January 1, 2017. Retrieved January 1, 2017.

- ^ Hunter, Douglas (October 9, 2012). Double Double: How Tim Hortons Became a Canadian Way of Life, One Cup at a Time. HarperCollins. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4434-0675-8. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Learning, adapting key to Tim Hortons' success". Sudbury.com. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- ^ "Penguins sign Tim Horton to one year pact". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. September 3, 1971. p. B5.

- ^ "Dough may decide Tim Horton's future". Pittsburgh Press. June 6, 1972. p. 33.

- ^ "Sabres draft Horton from Pens on gamble". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 6, 1972. p. 19.

- ^ Blackman, Ted (February 22, 1974). "Right to the end, Tim Horton showed how to play the game". The Gazette. Montreal. p. 29.

- ^ Bailey, Budd (June 4, 2010). This day in Buffalo sports history: a toast Archived July 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Buffalo News. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ CBC Sports (January 31, 2009). "Doug Gilmour honoured by Maple Leafs". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Toronto Mapleleafs - Alumni - Toronto Maple Leafs - Team". National Hockey League. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Iaboni, John. "'Honoured Players Process Different For Leafs' in Leafs Game Day, Issue No. 3, 2005-06". Toronto Maple Leafs. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved April 6, 2007.

- ^ Johnston, Chris. "'Maple Leafs retire all honoured numbers and Dave Keon's No. 14'". Sportsnet. Retrieved October 15, 2016.

- ^ Commito, Mike; Snyder, Lorraine (January 23, 2008). "Tim Horton | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ Cole, Stephen (2006). The Canadian Hockey Atlas. Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0-385-66093-8.

- ^ "Ron Joyce Co-Founder, Tim Hortons/Chairman Emeritus". Tim Hortons. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Saltzman, Aaron (January 5, 2018). "Multiple Tim Hortons franchises, other businesses cut pay, benefits, citing minimum wage hike". CBC News. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Tim Horton Autopsy Police Report and Other Docs". Glen McGregor. February 20, 2011.

- ^ Shea, Kevin (December 13, 2002). "One on One With Tim Horton". Hockey Hall of Fame and Museum.

- ^ a b Iorfida, Chris (February 21, 2013). "Remembering Tim Horton". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ a b c Griggs, Tim; Horton, Lori (1997). In Loving Memory: A Tribute to Tim Horton. ECW Press. ISBN 9781550223194.

- ^ a b Popplewell, Brett (December 25, 2013). "Greatest Maple Leafs: No. 7 Tim Horton". Sportsnet.

- ^ a b McGregor, Glen (February 21, 2014). "Marking Tim Horton's death, 40 years after". Ottawa Citizen.

- ^ Whatever Happened To -?

- ^ "Horton killed in auto crash". Pittsburgh Press. United Press International. February 21, 1974. p. 28.

- ^ CBC Sports (December 26, 2000). "Horton widow dead at 68". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Buffalo Sabres Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on June 18, 2012.

- ^ "2015 Bruce Prentice Legacy Award - Tim Horton". oshof.ca. Ontario Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ "Toronto Maple Leafs retire the numbers of 17 players". National Hockey League. October 15, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

External links

- Biographical information and career statistics from NHL.com, or Eliteprospects.com, or Hockey-Reference.com, or Legends of Hockey, or The Internet Hockey Database

- The Canadian Encyclopedia: Tim Horton

- Biography at Tim Hortons corporate site

- 1930 births

- 1974 deaths

- Buffalo Sabres players

- Businesspeople in coffee

- Canadian expatriate ice hockey players in the United States

- Canadian ice hockey defencemen

- Fast-food chain founders

- Hockey Hall of Fame inductees

- Ice hockey people from Ontario

- National Hockey League players with retired numbers

- New York Rangers players

- People from Cochrane, Ontario

- Pittsburgh Hornets players

- Pittsburgh Penguins players

- Stanley Cup champions

- Tim Hortons

- Toronto Maple Leafs players

- Toronto St. Michael's Majors players

- Road incident deaths in Canada

- Accidental deaths in Ontario

- Alcohol-related deaths in Canada

- Drug-related deaths in Canada

- Burials at York Cemetery, Toronto