Tuckasegee River

| Tuckasegee River | |

|---|---|

View upriver from Old River Rd. above Bryson City | |

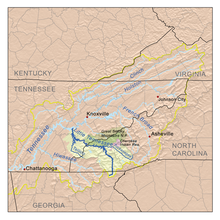

The Little Tennessee drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | confluence of Panthertown and Greenland creeks |

| • coordinates | 35°10′6″N 83°0′41″W / 35.16833°N 83.01139°W |

| • elevation | 3,969 ft (1,210 m) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Lake Fontana |

• coordinates | 35°26′5″N 83°35′4″W / 35.43472°N 83.58444°W |

• elevation | 1,703 ft (519 m) |

| Length | 60 mi (97 km) |

| Basin size | 655 sq mi (1,700 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Bryson City |

| • average | 1,584 cu ft/s (44.9 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 31 cu ft/s (0.88 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 61,600 cu ft/s (1,740 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Little Tennessee → Tennessee → Ohio → Mississippi |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | West Fork Tuckasegee River, Savannah Creek, Barkers Creek, Connelley Creek, Kirkland Creek |

| • right | Tanasee Creek, Caney Fork, Wayehutta Creek, Mill Creek, Scott Creek, Dicks Creek, Camp Creek, Oconaluftee River, Cooper Creek, Deep Creek, Lands Creek, Dicks Creek, Noland Creek, Forney Creek |

The Tuckasegee River (variant spellings include Tuckaseegee and Tuckaseigee)[1] flows entirely within western North Carolina. It begins its course in Jackson County below Cullowhee at the confluence of Panthertown and Greenland creeks.

It flows in a northwesterly direction into Swain County, where the Oconaluftee flows into it before the Tuckaseegee heads northwest. The county seat, Bryson City developed along both sides of the Tuckaseegee, and Bryson City Island Park was developed. The river next enters Fontana Lake, formed by the Fontana Dam upriver on the Little Tennessee River. The Tuckaseegee ultimately flows as a tributary into the Little Tennessee River below the lake.

The name Tuckasegee may be an anglicization or transliteration of the Cherokee word daksiyi—[takhšiyi] in the local Cherokee variety, meaning 'Turtle Place.' Several Cherokee towns developed along the river, including Kituwa, believed to be the "mother town" of the Cherokee. It developed around an earthen platform mound, likely built about 1000 CE. The mound, although reduced in height, is visible on the 309 acres (1.25 km2) of land reacquired in 1996 by the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. This land also includes the former site of an early 18th-century Cherokee town. The EBCI conducted an archeological survey in 1997 that found evidence of thousands of years of habitation at this site and are keeping it undeveloped as sacred ground.[2]

Many of the mounds in this area were built by about 1000 CE, during the South Appalachian Mississippian culture era. In each of their major towns, the Cherokee built a townhouse as their expression of public architecture on top of such a mound, if it existed. The townhouse was the Cherokee expression of public architecture, emphasizing their decentralized society based on community consensus. In some places, they built a townhouse on the main town plaza.[3]

The river also has several stone fishing weirs built by prehistoric indigenous peoples. It is believed that the weirs were built by peoples who lived here prior to the Cherokee in the Southeast. The weirs are most easily viewed when water levels are low. One near Webster, North Carolina, is the most intact and has a characteristic "V" shape.[4]

Fishing, hiking, and paddling are among the recreational opportunities along the river.

References

[edit]- ^ "Tuckasegee River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Andrea (Fall 2009). "Embracing Archeology". American Archeology. 13 (3). Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Rodning, Christopher B. (October 2009). "Mounds, Myths, and Cherokee Townhouses in Southwestern North Carolina". American Antiquity. 74 (4): 627–663. doi:10.1017/S000273160004899X. JSTOR 20622469. S2CID 160280780. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Anne Frazier Rogers, "Fish weirs as part of the cultural landscape," Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers, National Park Service.