Hook-and-loop fastener

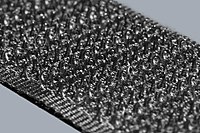

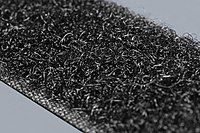

Hook-and-loop fasteners, also known as hook-and-pile fasteners or touch fasteners, are devices that allow two surfaces to be repeatedly fastened and unfastened, commonly used in clothing and other applications. They are often referred to by the genericized trademark velcro, which was the original name given by the inventor. The fastener consists of two components: typically, two linear fabric strips or smaller segments that are attached—sewn or otherwise adhered—to opposing surfaces designed to be fastened together. One component features tiny hooks, and the other features smaller loops. When the two are pressed together, the hooks catch in the loops, and the two pieces fasten or bind temporarily. Separation can be achieved by pulling or peeling the two surfaces apart, during which the strips produce a distinctive ripping sound.

History

[edit]

The original hook-and-loop fastener was conceived in 1941 by Swiss engineer George de Mestral,[1][2][3] which he named velcro. The idea came to him one day after returning from a hunting trip with his dog in the Alps. He took a close look at the burs of burdock that kept sticking to his clothes and his dog's fur. He examined them under a microscope, and noted their hundreds of "hooks" that caught on anything with a loop, such as clothing, animal fur, or hair.[4] He saw the possibility of binding two materials reversibly in a simple fashion if he could figure out how to duplicate the hooks and loops.[1][3] Hook-and-loop is regarded by some like Steven Vogel[5] or Werner Nachtigall[6] as a key example of inspiration from nature or the copying of nature's mechanisms (called bionics or biomimesis).

The big breakthrough de Mestral made was to think about hook-and-eye closures on a greatly reduced scale. Hook-and-eye fasteners have been common for centuries, but what was new about hook-and-loop fasteners was the miniaturisation of the hooks and eyes. Shrinking the hooks led to the two other important differences. Firstly, instead of a single-file line of hooks, hook-and-loop fasteners have a two-dimensional surface.[7] This was needed, because in decreasing the size of the hooks, the strength was also unavoidably lessened, thus requiring more hooks for the same strength. The other difference is that hook-and-loop has indeterminate match-up between the hooks and eyes. With larger hook-and-eye fasteners, each hook has its own eye. On a scale as small as that of hook-and-loop fasteners, matching up each of these hooks with the corresponding eye is impractical, thus leading to the indeterminate matching.[7]

De Mestral's proposal was initially rejected by industry leaders when he took his idea to Lyon, which was then a center of weaving. He did manage to gain the assistance of one weaver, who produced two cotton strips based on de Mestral's designs. However, the cotton frayed and wore out in a relatively short period of time. As a result, de Mestral began to explore the use of synthetic fibers, believing that they would provide a more resilient product.[4] De Mestral eventually selected nylon, on the reasoning that it does not easily fray or attract mold, is non-biodegradable, and could be produced in threads of varying thickness.[8] Nylon had only recently been invented, and through trial and error de Mestral eventually discovered that, when sewn under hot infrared light, nylon forms small hook shapes.[1] However, he had yet to figure out a way to mechanize the process and to make the looped side. Next he found that nylon thread, when woven in loops and heat-treated, retains its shape and is resilient; however, the loops had to be cut in just the right spot so that they could be fastened and unfastened many times. On the verge of giving up, a new idea came to him. He bought a pair of shears and trimmed the tops off the loops, thus creating hooks that would match up perfectly with the loops in the pile.[4]

Mechanizing the process of weaving the hooks took eight years, and it took another year to create the loom that trimmed the loops after weaving them. In all, it took ten years to create a mechanized process that worked.[4]

De Mestral submitted his idea for a patent in Switzerland in 1951, which was granted in 1955.[1] Within a few years he obtained patents and began to open shops in Germany, Switzerland, Great Britain, Sweden, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Canada. In 1957 he branched out to the textile center of Manchester, New Hampshire in the United States.

Columnist Sylvia Porter made the first mention of the product in her column Your Money's Worth of August 25, 1958, writing, "It is with understandable enthusiasm that I give you today an exclusive report on this news: A 'zipperless zipper' has been invented – finally. The new fastening device is in many ways potentially more revolutionary than was the zipper a quarter-century ago."[9]

A Montreal firm, Velek, Ltd., acquired the exclusive right to market the product in North and South America, as well as in Japan, with American Velcro, Inc. of New Hampshire, and Velcro Sales of New York, marketing the "zipperless zipper" in the United States.[9]

De Mestral obtained patents in many countries right after inventing the fasteners, as he expected an immediate high demand. Partly due to its cosmetic appearance, though, hook-and-loop's integration into the textile industry took time.[citation needed] At the time, the fasteners looked like they had been made from leftover bits of cheap fabric, and thus were not sewn into clothing or used widely when it debuted in the early 1960s.[10] It was also regarded as impractical.[10]

A number of Velcro Corporation products were displayed at a fashion show at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel in New York in 1959,[11] and the fabric got its first break when it was used in the aerospace industry to help astronauts maneuver in and out of bulky space suits. However, this reinforced the view among the populace that hook-and-loop was something with very limited utilitarian uses. The next major use hook-and-loop saw was with skiers, who saw the similarities between their outerwear and that of the astronauts, and thus saw the advantages of a suit that was easier to don and doff. Scuba and marine gear followed soon after. Having seen astronauts storing food pouches on walls,[12] children's clothing makers came on board.[10] As hook-and-loop fasteners only became widely used after NASA's adoption of it, NASA is popularly – and incorrectly – credited with its invention.

By the mid-1960s, hook-and-loop fasteners were used in the futuristic creations of fashion designers such as Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges and Paco Rabanne.[13]

Later improvements included strengthening the filament by adding polyester.[8]

In 1978, de Mestral's patent expired, prompting a flood of low-cost imitations from Taiwan, China and South Korea onto the market. Today, the trademark is the subject of more than 300 trademark registrations in over 159 countries.[specify] George de Mestral was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in the U.S. for his invention.[4]

Strength

[edit]

Various constructions and strengths are available. Fasteners made of Teflon loops, polyester hooks, and glass backing are used in aerospace applications, e.g. on Space Shuttles. The strength of the bond depends on how well the hooks are embedded in the loops, how much surface area is in contact with the hooks, and the nature of the force pulling it apart. If hook-and-loop is used to bond two rigid surfaces, such as auto body panels and frame, the bond is particularly strong because any force pulling the pieces apart is spread evenly across all hooks. Also, any force pushing the pieces together is disproportionately applied to engaging more hooks and loops. Vibration can cause rigid pieces to improve their bond. Full-body hook-and-loop suits have been made that can hold a person to a suitably covered wall.

When one or both of the pieces is flexible, e.g., a pocket flap, the pieces can be pulled apart with a peeling action that applies the force to relatively few hooks at a time. If a flexible piece is pulled in a direction parallel to the plane of the surface, then the force is spread evenly, as it is with rigid pieces.

Three ways to maximize the strength of a bond between the two flexible pieces are:

- Increase the area of the bond, e.g. using larger pieces.

- Ensure that the force is applied parallel to the plane of the fastener surface, such as bending around a corner or pulley.

- Increase the number of hooks and loops per area unit.

Shoe closures can resist a large force with only a small amount of hook-and-loop fasteners. This is because the strap is wrapped through a slot, halving the force on the bond by acting as a pulley system (thus gaining a mechanical advantage), and further absorbing some of the force in friction around the tight bend. This layout also ensures that the force is parallel to the strips.

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Hook-and-loop fasteners are safe and maintenance free. There is only a minimal decline in effectiveness even after many fastenings and unfastenings. The tearing noise it makes can also be useful against pickpockets. This loud noise can also prove to be a liability, in particular on military attire such as the United States Army's Army Combat Uniform, where it can attract unwanted attention in a battlefield environment.

There are also some deficiencies: it tends to accumulate hair, dust, and fur in its hooks after a few months of regular use. The loops can become elongated or broken after extended use. The hooks often become attached to articles of clothing, especially loosely woven items like sweaters. This clothing may be damaged when one attempts to remove the hook-and-loop, even if the sides are separated slowly. It also absorbs moisture and perspiration when worn next to the skin, which means it will smell if not washed.

Applications

[edit]Because of their ease of use, hook-and-loop fasteners have been used for a wide variety of applications where a temporary bond is required. It is especially popular in clothing where it replaces buttons or zippers, and as a shoe fastener for children who have not yet learned to tie shoelaces. Hook-and-loop fasteners are used in adaptive clothing, which is designed for people with physical disabilities, the elderly, and the infirm, who may experience difficulty dressing themselves due to an inability to manipulate closures such as buttons and zippers.

Hook-and-loop-fastener (USA Patent No.: US8,469,996 B2) is used in humans as a temporary fascia expander prostheses to treat the abdominal compartment syndrome and when multiple abdominal entries are necessary to control and eliminate intra-abdominal pathology. Hook-and-loop fasteners held together a human heart during the first artificial heart surgery. It is used in nuclear power plants and army tanks to hold flashlights to walls. In cars, hook-and-loop fasteners are used to bond headliners, floor mats and speaker covers. It is used in the home when pleating draperies, holding carpets in place and attaching upholstery.[4] Closures on backpacks, briefcases and notebooks often make use of hook-and-loop fasteners. Cloth diapers often make use of hook-and-loop fasteners. It is an integral part of games such as tag rugby and flag football, and is used in surfboard leashes and orthopaedic braces.

NASA makes significant use of hook-and-loop fasteners. Each Space Shuttle flew equipped with ten thousand inches of a special fastener made of Teflon loops, polyester hooks, and glass backing.[8] Hook-and-loop fasteners are widely used, from the astronauts' suits, to anchoring equipment. In the near weightless conditions in orbit, hook-and-loop fasteners are used to temporarily hold objects and keep them from floating away.[14] A patch is used inside astronauts' helmets where it serves as a nose scratcher.[4][8] During mealtimes astronauts use trays that attach to their thighs using springs and fasteners.[12] Hook-and-loop fasteners are also used aboard the International Space Station.

Guitar pedals are commonly attached to pedalboards with strips of hook-and-loop.

Variations

[edit]

The Slidingly Engaging Fastener was developed to address several problems with common hook-and-loop fasteners.[15][16] Heavy-duty variants (such as "Dual Lock" or "Duotec") feature mushroom-shaped stems on each face of the fastener, providing an audible snap when the two faces mate. A strong pressure sensitive adhesive bonds each component to its substrate.

There is a silent version of hook-and-loop fasteners, sometimes called Quiet Closures.

Standards

[edit]- ASTM D5169-98 (2010) Standard Test Method for Shear Strength (Dynamic Method) of Hook and Loop Touch Fasteners

- ASTM D5170-98 (2010) Standard Test Method for Peel Strength ("T" Method) of Hook and Loop Touch Fasteners

- ASTM D2050-11 Standard Terminology Relating to Fasteners and Closures Used with Textiles

Jumping

[edit]Velcro jumping is a game where people wearing hook-covered suits take a running jump and hurl themselves as high as possible at a loop-covered wall.[8][17] The wall is inflated, and looks similar to other inflatable structures. It is not necessarily completely covered in the material—often there will be vertical strips of hooks. Sometimes, instead of a running jump, people use a small trampoline.

Television show host David Letterman immortalized this during the February 28, 1984 episode of Late Night with David Letterman on NBC. Letterman proved that with enough of the material a man could be hurled against a wall and stick, by performing this feat during the television broadcast.[4][10][17]

Jumping went beyond David Letterman, with amusement companies renting walls and jumpsuits for $400–500 a day.[17] It was also done on a regular basis in pubs in both New York and New Zealand, where it is a competition to see how high a person can get their feet above the ground.[18] Jeremy Bayliss and Graeme Smith of the Cri Bar and Grill in Napier, New Zealand, started it after seeing American astronauts sticking to walls during space flights. They created their own equipment for the "human fly" contests, and sold it to several others in New Zealand.[18] By 1992, wall-jumping was practiced in dozens of New Zealand bars and was said to be one of the favorite bar activities there at the time.[18]

The game had moved to the U.S. after Sports Illustrated published a story on it in 1991. Adam Powers and Stephen Wastell of the Perfect Tommy's bar in New York city read of the game, and soon became the United States distributor of Human Bar Fly equipment.

In popular culture

[edit]- 1969–1972 - Velcro brand fasteners were used on the suits, sample collection bags, and lunar vehicles during all Apollo program missions to the Moon.[19] The investigation board for the Apollo 1 incident cited the prevalence of Velcro—almost 34 square feet (3.2 m2)—near the ignition source as part of the combustible material near the fire in the command module, which caused the deaths of astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee.[20]

- 1966–1969 In Star Trek: The Original Series, Velcro was used instead of belts or holsters as a space-age way to attach phasers and communicators to crew uniforms.[21][22]

- 1984 - David Letterman wears a suit made of hook-and-loop and jumps from a trampoline into a wall covered in the product during an interview with Velcro Companies' USA director of industrial sales.[23]

- 1996 - In the John Frankenheimer film The Island of Dr. Moreau, Moreau's assistant jokingly claims that the doctor won his Nobel Prize for inventing Velcro.[24]

- 1997 - The fastener has become part of a recurring joke in various media in which it is claimed that modern humans would be unable to invent it, and that it is in fact a form of advanced technology. For example, K claims in Men in Black that Velcro was originally alien technology,[25]

- 2002 - The Star Trek: Enterprise episode "Carbon Creek" portrays Velcro as being introduced to human society by Vulcans in 1957. One of the Vulcans in the episode is named "Mestral", after the fastener's actual inventor and founder of the brand.[26]

- 2004 - One of the characters in the film Garden State made a vast fortune from inventing "silent Velcro".[27]

- 2016 - As an April Fools' Day joke Lexus introduced "Variable Load Coupling Rear Orientation (V-LCRO)" seats, technology that attaches the driver to the seat with Velcro Brand product to allow for more aggressive turns.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Stephens, Thomas (2007-01-04). "How a Swiss invention hooked the world". swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on 2024-02-11. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ McSweeney, Thomas J.; Stephanie Raha (August 1999). Better to Light One Candle: The Christophers' Three Minutes a Day: Millennial Edition. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8264-1162-4. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b "About us: History". Velcro.us. Archived from the original on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strauss, Steven D. (December 2001). The Big Idea: How Business Innovators Get Great Ideas to Market. Kaplan Business. pp. 15–pp.18. ISBN 978-0-7931-4837-0. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Steven Vogel (1988). Life's Devices: The Physical World of Animals and Plants. ISBN 978-0-691-02418-9.

- ^ Nachtigall, W. 1974. Biological Mechanisms of Attachment: the comparative morphology and bionengineering of organs for linkage New York : Springer-Verlag

- ^ a b Weber, Robert John (February 1993). Forks, Phonographs, and Hot Air Balloons: A Field Guide to Inventive Thinking. Oxford University Press. pp. 157–160. ISBN 978-0-19-506402-5. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b c d e Schwarcz, Joseph A. (October 2003). Dr. Joe & What You Didn't Know: 99 Fascinating Questions About the Chemistry of Everyday Life. Ecw Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-55022-577-8. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

But not every Velcro application has worked ... A strap-on device for impotent men also flopped.

- ^ a b Sylvia Porter, "Your Money's Worth", Syracuse Herald-Journal, August 25, 1957, p21

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Allyn; Bob Golden (September 1997). Why Didn't I Think of That: Bizarre Origins of Ingenious Inventions We Couldn't Live Without. Wiley. pp. 99–pp.104. ISBN 978-0-471-16511-8. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (June 15, 2010) A Brief History of: Velcro, Time.com, Archived at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Jones, Thomas; Benson, Michael (January 2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to NASA. Alpha. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-0-02-864282-6. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Jane Pavitt (2008-09-01). Fear and fashion in the Cold War. Victoria & Albert Museum. ISBN 978-1-85177-544-6.

- ^ Jones, Thomas; Michael Benson (January 2002). The Complete Idiot's Guide to NASA. Alpha. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-02-864282-6. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ Mone, Gregory (2007-05-14). "Invention awards The New Velcro". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2008-01-28. Retrieved 2024-01-15.

- ^ Body Beauty (2007-06-11). "Velcro Reinvented". InventorSpot.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-26. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b c Sennett, Frank (November 2004). 101 Stunts for Principals to Inspire Student Achievement. Corwin Press. p. 86. ISBN 076198836X. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ^ a b c Kleinfield, N. R. (1992-01-05). "Fly Through Air, Hit a Wall. Now Stay There". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-09-11. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ "Working on the Moon". Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Emanuelli, Matteo. "The Apollo 1 Fire". Space Safety Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ "How were the original Star Trek phasers holstered without a belt or a pocket?". Science Fiction & Fantasy Stack Exchange. Archived from the original on 2023-08-29. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ "Star Trek: The Original Series Props – Auction House Archive, Part 1". Movie Prop Collecting with Jason DeBord's Original Prop Blog Film & TV Prop, Costume, Hollywood Memorablia Pop Culture Resource. 2008-04-18. Archived from the original on 2024-09-11. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ "LiveScience: Who Invented Velcro?". Live Science. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (1996-08-23). "The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-09-11. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ Tatara, Paul (1997-07-04). "'Men in Black:' DO believe the hype". CNN. Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "Startrek.com:Carbon Creek". Startrek.com. CBS Studios. Archived from the original on 2009-08-28. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (2004-07-28). "Garden State (2004)". New York Times. Archived from the original on 2024-09-11. Retrieved 2008-05-11.

- ^ "TIME: Best April Fools Day Jokes". Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hook-and-loop fasteners at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hook-and-loop fasteners at Wikimedia Commons