Marco Polo: Difference between revisions

→Controversies: tag who |

→Controversies: removing this (unreferenced) claim about the alternate birthplace, because this 'controversy' is already covered in note 3 (with refs) |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

==Controversies== |

==Controversies== |

||

{{refimprove}} |

{{refimprove}} |

||

Since the mid of the 19th century a number of sources,{{who}} for the most part Croatian, have claimed that Marco Polo was born on the island of [[Korčula]] (the Venetian ''Curzola''), in present-day [[Croatia]], and that he was consequently of Croat ethnicity. Both claims are controversial. |

|||

Some modern historians question the veracity of Marco Polo's account, and wonder whether he really visited the Mongol empire, or whether Marco Polo was simply repeating stories that he had heard from other traders. Dr. Frances Wood has questioned whether or not Marco Polo was even in China, and has pointed out several things that a European traveler probably would have mentioned, but which Polo did not, and that there is no mention of Marco Polo in Chinese accounts of the period.<ref>{{cite book|title=Did Marco Polo Go To China?|last=Wood|first=Frances|publisher=Secker & Warburg|location=London|year=1995}}</ref> Historian [[Peter Jackson (historian)|Peter Jackson]] argues that there are several different versions of Polo's book, and questions whether it even represents Polo's account at all, but was instead simply written by a romance writer of the time. Questions have also been raised as to whether Marco Polo, if he did visit China, was genuinely an ambassador, or if he was simply one of the many travelers at the time who claimed to be an ambassador.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Marco Polo and his 'Travels'|author=[[Peter Jackson (historian)|Jackson, Peter]]|journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies|volume=61|issue=1|date=1998|pages=82–101}}</ref> However, [[Laurence Bergreen]], in his book, ''Marco Polo From Venice to Xanadu'', writes "it would have been a more amazing feat to amass so much accurate information about Asia without actually going there, than to have made the trip and write about it."{{fact}} |

Some modern historians question the veracity of Marco Polo's account, and wonder whether he really visited the Mongol empire, or whether Marco Polo was simply repeating stories that he had heard from other traders. Dr. Frances Wood has questioned whether or not Marco Polo was even in China, and has pointed out several things that a European traveler probably would have mentioned, but which Polo did not, and that there is no mention of Marco Polo in Chinese accounts of the period.<ref>{{cite book|title=Did Marco Polo Go To China?|last=Wood|first=Frances|publisher=Secker & Warburg|location=London|year=1995}}</ref> Historian [[Peter Jackson (historian)|Peter Jackson]] argues that there are several different versions of Polo's book, and questions whether it even represents Polo's account at all, but was instead simply written by a romance writer of the time. Questions have also been raised as to whether Marco Polo, if he did visit China, was genuinely an ambassador, or if he was simply one of the many travelers at the time who claimed to be an ambassador.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Marco Polo and his 'Travels'|author=[[Peter Jackson (historian)|Jackson, Peter]]|journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies|volume=61|issue=1|date=1998|pages=82–101}}</ref> However, [[Laurence Bergreen]], in his book, ''Marco Polo From Venice to Xanadu'', writes "it would have been a more amazing feat to amass so much accurate information about Asia without actually going there, than to have made the trip and write about it."{{fact}} |

||

Revision as of 13:01, 19 July 2009

Marco Polo | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Marco Polo[Note 1] | |

| Born | c. 1254 Venice, Italy |

| Died | January 8, 1324 (aged 69) Venice, Italy |

| Resting place | Church of San Lorenzo 45°15′41″N 12°12′15″E / 45.2613°N 12.2043°E |

| Nationality | Venetian (Italian) |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, Explorer |

| Known for | The Travels of Marco Polo |

| Spouse | Danta Badoer |

| Children | Fantina, Bellela, and Moretta |

| Parent(s) | Mother: Unknown Father: Niccolò Polo |

Marco Polo (English pronunciation: /ˈmɑrkoʊ ˈpoʊloʊ/ ) (c. 1254 – January 8, 1324) was an explorer from the Venetian Republic who wrote Il Milione, which introduced Europeans to Central Asia and China. He learned about trading whilst his father and uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, voyaged through Asia and met Kublai Khan. In 1269, they returned to Venice and were reunited with Marco. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, returning after 24 years to find Venice at war with Genoa; Marco was imprisoned, and dictated his stories to a cellmate. He was released in 1299, became a wealthy merchant, married and had 3 children. He died in 1324, and was buried in San Lorenzo.

Il Milione was translated, embellished, copied by hand and adapted; there is no authoritative version. It documents his father's journey to meet the Kublai Khan, who asked them to become ambassadors, and communicate with the pope. This lead to Marco's quest, through Acre, into China and to the Mongol court. Marco wrote of his extensive travels throughout Asia on behalf of the Khan, and their eventual return after Template:Mi to km and 24 years of adventures.

Their pioneering journey inspired Columbus and others, opening the Silk Road. Marco Polo's legacies includes Venice Marco Polo Airport, the Marco Polo sheep, and several books and films. He also impacted European cartography, leading to the introduction of the Fra Mauro map.

Life

Childhood through captivity

Marco Polo was born in 1254,[Note 2] in Venice, Italy.[Note 3][1] His father Niccolò was a merchant who traded with the Middle East, becoming wealthy and achieving great prestige.[2][3] Niccolò and his brother Maffeo set off on a trading voyage, before Marco was born.[3] In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo were residing in Constantinople when they foresaw a political change; they liquidated their assets into jewels and moved away.[2] According to The Travels of Marco Polo, they passed through much of Asia, and met with the Kublai Khan.[4] Meanwhile, Marco Polo's mother died, and he was raised by an aunt and uncle.[3] Polo was well educated, and learned merchant subjects including foreign currency, appraising, and the handling of cargo ships,[3] although he learned little or no Latin.[2]

In 1269, Niccolò and Maffeo returned to Venice, meeting Marco for the first time. In 1271, Marco Polo (at seventeen years of age), his father, and his uncle set off for Asia on the series of adventures that were later documented in Marco's book. They returned to Venice in 1295, 24 years later, with many riches and treasures. They had travelled almost 15,000 miles (24,140 km).[3]

Upon their return, Venice was at war with Genoa, and Marco Polo was taken prisoner. He spent the few months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa,[3] who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes and current affairs from China. The book became known as The Travels of Marco Polo, and depicts the Polos' journeys throughout Asia, giving Europeans their first comprehensive look into the inner workings of the Far East, including China, India, and Japan.[citation needed] Marco Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299,[3] and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle had purchased a large house in the central quarter named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo. The company continued its activities and Marco soon became a wealthy merchant. Polo financed other expeditions, but never left Venice again. In 1300, he married Donata Badoer, the daughter of Vitale Badoer, a merchant.[5] They had three daughters, called Fantina, Bellela and Moreta.[6]

Death

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On January 8, 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed. To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices. The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried.[7] He also set free a "Tartar slave" who may have accompanied him from Asia.[8]

He divided up the rest of his assets, including several properties, between individuals, religious institutions, and every guild and fraternity to which he belonged. He also wrote-off multiple debts including three hundred lire that his sister-in-law owed him, and others for the convent of San Giovanni, San Paolo of the Order of Preachers, and a cleric named Friar Benvenuto. He ordered 220 soldi be paid to Giovanni Giustiniani for his work as a notary and his prayers.[7] The will, which was not signed by Polo, but was validated by then relevant "signum manus" rule, by which the testator only had to touch the document to make it abide to the rule of law[9], was dated January 9, 1324. Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact date of Marco Polo's death cannot be determined, but it was between the sunsets of January 8 and 9, 1324.[7]

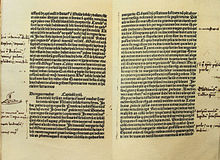

The Travels of Marco Polo

An authoritative version of Marco Polo's book does not exist, and the early manuscripts differ significantly. The published versions of his book rely on either single scripts, blend multiple versions together or add notes to clarify, for example in the English translation by Henry Yule. Another English translation by A.C. Moule and Paul Pelliot, published in 1938, is based on the Latin manuscript which was found in the library of the Cathedral of Toledo in 1932, and is 50% longer than other versions.[10] Approximately 150 variants in various languages are known to exist, and without the luxury of a printing press many errors were made during copying and translation, resulting in many discrepancies.[11]

Stories

The book starts with a preface about his father and uncle traveling to Bolghar where Prince Berke Khan lived. A year later, they went to Ukek,[12] and continued to Bukhara where an envoy from Levant invited them to meet Kublai Khan, who had never met Europeans.[13] In 1266, they reached the seat of the Kublai Khan at Dadu, present day Beijing, China. Khan received the brothers with hospitality and asked them many questions regarding the European legal and political system.[14] He also inquired about the Pope and Church in Rome.[15] After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). Kublai Khan requested that an envoy brings him back oil of the lamp in Jerusalem.[16] The long sede vacante between the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268 and the election of his successor delayed the Polos in fulfilling Khan's request. They followed the suggestion of Theobald Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt, and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at the age of fifteen or sixteen.[17]

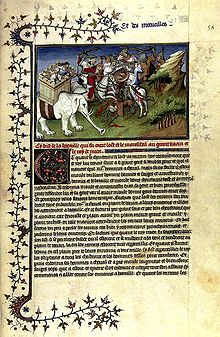

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfill Khan's request. They sailed to Acre, and then rode on camels to the Persian port of Hormuz. They wanted to sail to China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland until reaching Khan's summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou. Three and one-half years after leaving Venice, when Marco was about 21 years old, Khan welcomed the Polos into his palace.[3] The exact date of their arrival is unknown, but scholars estimate it to be between 1271 and 1275.[Note 4] On reaching the Mongol court, the Polos presented the sacred oil from Jerusalem and the papal letters to their patron.[2]

Marco knew four languages, and the family had accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience that was useful to Khan. It is possible that he became a government official;[3] he wrote about many imperial visits to China's southern and eastern provinces, the far south and Burma.[18]

Kublai Khan declined the Polos' requests to leave China. They became worried about returning home safely, believing that if Khan died, his enemies might turn against them because of their close involvement with the ruler. In 1292, Khan's great-nephew, then ruler of Persia, sent representatives to China in search of a potential wife, and they asked the Polos to accompany them, so they were permitted to return to Persia with the wedding party—which left that same year from Zaitun in southern China on a fleet of 14 junks. The party sailed to the port of Singapore, travelled north to Sumatra and around the southern tip of India, eventually crossing the Arabian Sea to Hormuz. From here, the Polos left the wedding party and travelled overland to the Turkish port of Trebizond, the present day Trabzon.[3]

Legacy

Further exploration

Other less well-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo's book meant that their journey was the first to be widely known. Christopher Columbus was inspired enough by Polo's description of the Far East to visit those lands for himself; a copy of the book was among his belongings, with handwritten annotations.[19] Bento de Góis, inspired by Polo's writings of a Christian kingdom in the east, travelled Template:Mi to km in three years across Central Asia. He never found the kingdom, but ended his travels at the Great Wall of China in 1605, proving that Cathay was what Matteo Ricci called "China".[20]

Commemoration

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of Ovis aries, is named after the explorer,[21] who described it during his crossing of Pamir (ancient Mount Imeon) in 1271.[Note 5] In 1851, a three-masted Clipper built in Saint John, New Brunswick also took his name; the Marco Polo was the first ship to sail around the world in under six months.[22] The airport in Venice is named Venice Marco Polo Airport,[23] and the frequent flyer program of Hong Kong flag carrier Cathay Pacific is known as the "Marco Polo Club".[24] The Travels of Marco Polo are fictionalised in Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne's Messer Marco Polo and Gary Jennings' 1984 novel The Journeyer. Polo also appears as the pivotal character in Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities. The 1982 television miniseries, Marco Polo, directed by Giuliano Montaldo and depicting Polo's travels, won two Emmy Awards and was nominated for six more.[25]

Cartography

Marco Polo's travels may have had some impact on the development of European cartography, ultimately leading to the European voyages of exploration a century later.[26] The 1453 Fra Mauro map was said by Giovanni Battista Ramusio to have been an improved copy of the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo:

That fine illuminated world map on parchment, which can still be seen in a large cabinet alongside the choir of their monastery (The Calmoldese monastery of Santo Michele on Murano) was by one of the brothers of the monastery, who took great delight in the study of cosmography, diligently drawn and copied from a most beautiful and very old nautical map and a world map that had been brought from Cathay by the most honourable Messer Marco Polo and his father.

Controversies

This article needs additional citations for verification. |

Some modern historians question the veracity of Marco Polo's account, and wonder whether he really visited the Mongol empire, or whether Marco Polo was simply repeating stories that he had heard from other traders. Dr. Frances Wood has questioned whether or not Marco Polo was even in China, and has pointed out several things that a European traveler probably would have mentioned, but which Polo did not, and that there is no mention of Marco Polo in Chinese accounts of the period.[27] Historian Peter Jackson argues that there are several different versions of Polo's book, and questions whether it even represents Polo's account at all, but was instead simply written by a romance writer of the time. Questions have also been raised as to whether Marco Polo, if he did visit China, was genuinely an ambassador, or if he was simply one of the many travelers at the time who claimed to be an ambassador.[28] However, Laurence Bergreen, in his book, Marco Polo From Venice to Xanadu, writes "it would have been a more amazing feat to amass so much accurate information about Asia without actually going there, than to have made the trip and write about it."[citation needed]

See also

- Kublai Khan, leader of the Mongol Empire (1260 to 1294), grandson of Ghengis Khan.

- Niccolò and Maffeo Polo, the father and uncle of Marco.

- The Silk Road, which Marco Polo was the first European to travel.

Notes

- ^ The exact source is unknown, but the portrait originated from a 16th century painting in the Gallery of Monsignor Badia in Rome. Inscription: Marcus Polus venetus totius orbis et Indie peregrator primus. It appears in the Nordisk familjebok Berg 1915, p. 1261

- ^ Many sources state this date; Britannica 2002, p. 571 states, "born in or around 1254. (This date, like nearly all the others concerning major events in his life, is conjectural.)"

- ^ Some sources (e.g. Burgan 2002, p. 7) suggest that Polo was born in Korčula, an island in Dalmatia, now Croatia. The Korcula info website states, "Polo is reputed to have been born in Korcula itself, although evidence to support this thesis is at best sketchy." A "Birthpace of Marco Polo" exists on the island (website).

- ^ Drogön Chögyal Phagpa, a Tibetan monk and confidant of Kublai Khan, mentions in his diaries that in 1271 a foreign friend of Kublai Khan visits — quite possibly one of the elder Polos or even Marco Polo himself, although, no name was given. If this is not the case, a more likely date for their arrival is 1275 (or 1274, according to the research of Japanese scholar Matsuo Otagi).(Britannica 2002, p. 571)

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch.18 states, "Then there are sheep here as big as asses; and their tails are so large and fat, that one tail shall weigh some 30 lb. They are fine fat beasts, and afford capital mutton."

References

- ^ Bergreen 2007, p. 25

- ^ a b c d Brittanica 2002, p. 571

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Parker 2004, pp. 648–649

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch.1–9

- ^ Bergreen 2007, p. 532

- ^ Power 2007, p. 87

- ^ a b c Bergreen 2007, pp. 339–342

- ^ Britannica 2002, p. 573

- ^ Biblioteca Marciana, the institute that holds Polo's original copy of his testament. http://marciana.venezia.sbn.it/admin/filemanager/file/UserFiles/File/testamento-polo.txt

- ^ Bergreen 2007, pp. 367–368

- ^ Edwards, p. 1

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 2

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 3

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 5

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 6

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 7

- ^ Yule & Cordier 1923, ch. 9

- ^ W. Marsden (2004), Thomas Wright (ed.), The Travels pf Marco Polo, The Venetian (1298) (PDF), retrieved 2009-07-14

- ^ Landström 1967, p. 27

- ^ Winchester 2008, p. 264

- ^ Bergreen 2007, p. 74

- ^ Lubbock 2008, p. 86

- ^ Brennan, D. (2009-02-01), Lost in Venice, WalesOnline, retrieved 2009-07-15

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Cathay Pacific Airways, The Marco Polo Club, Cathay Pacific Airways Limited, retrieved 2009-07-13

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|data=ignored (|date=suggested) (help) - ^ Academy of Television Arts & Sciences, retrieved 2009-07-06 (Searching for "Marco Polo", and year 1982)

- ^ a b Falchetta 2006, p. 592

- ^ Wood, Frances (1995). Did Marco Polo Go To China?. London: Secker & Warburg.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1998). "Marco Polo and his 'Travels'". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 61 (1): 82–101.

Bibliography

- Basil, Lubbock (2008), The Colonial Clippers, Read Books, ISBN 9781443771191

- Berg, R. G:son; Söderberg, V. (1915), [[Nordisk familjebok]] (en. Nordic familybook) (in Swedish) (Uggleupplagan ed.), Stockholm: Project Runeberg

{{citation}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Bergreen, Laurence (2007), Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu, London: Quercus, ISBN 9781847243454

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Britannica Editors (2002), "Marco Polo", The New Encyclopædia Britannica Macropedia, vol. 9 (15 ed.), Encyclopaedia Brittanica, Inc, ISBN 9780852297872

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Burgan, Michael (2002), Marco Polo: Marco Polo and the silk road to China, Mankato: Compass Point Books, ISBN 9780756501808

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Edwards, Mike (2005), Marco Polo, Part 1, Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society

- Falchetta, Piero (2006), Fra Mauro's World Map, Turnhout: Brepols, ISBN 2503517269

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Landström, Björn (1967), Columbus: the story of Don Cristóbal Colón, Admiral of the Ocean, New York City: Macmillan

- McKay, John (2006), A History of Western Society (Eighth ed.), Houghton Mifflin Company, p. 506, ISBN 0618522662

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Parker, John (2004), "Marco Polo", The World Book Encyclopedia, vol. 15 (illustrated ed.), United States of America: World Book, Inc., ISBN 9780716601043

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Power, Eileen Edna (2007), Medieval People, BiblioBazaar, ISBN 9781426467776

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Winchester, Simon (2008-05-06), The Man Who Loved China: Joseph Needham and the Making of a Masterpiece, New York: HarperCollins, ISBN 9780060884598

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Yule, Henry; Cordier, Henri (1923), The Travels Of Marco Polo, Mineola: Dover Publications, ISBN 9780486275864

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Daftary, Farhad (1994), The Assassin legends: myths of the Ismaʻilis (2 ed.), I.B. Tauris, p. 213, ISBN 9781850437055

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hart, H. Henry (1948), Marco Polo, Venetian Adventurer, Kessinger Publishing

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Otfinoski, Steven (2003), Marco Polo: to China and back, New York: Benchmark Books, ISBN 0761414800

{{citation}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links

- National Geographic Marco Polo: Journey from Venice to China

- In the Footsteps of Marco Polo: A Journey through the Met to the Land of the Great Khan

- Template:Dmoz

- Works by Marco Polo at Project Gutenberg

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Template:Imdb character