Pseudoscience: Difference between revisions

removing link to the testability and removing this specific criterion, not because it's wrong, but because it doesn't belong in the intro. Various criteria are set forth in the article already |

→Psychology: Pseudoscience in Clincal Psychology |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image: |

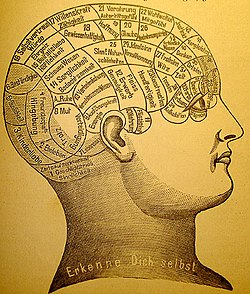

[[Image:Phrenology1.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Phrenology]] is regarded today as a classic example of pseudoscience. It was, however, the first attempt to assign specific areas of the brain with certain functions -- an important precursor to modern [[neuroscience]].]] |

||

'''Pseudoscience''' is any kind of knowledge, belief, or practice that claims to be scientific but does not follow the [[scientific method]].<ref>"''Pseudoscientific - pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific''", from the ''Oxford American Dictionary'', published by the [[Oxford English Dictionary]].</ref> Pseudosciences may appear scientific, but they do not adhere to the basic requirements (the testability and repeatability) of the scientific method. As such, since these practices are not proven by the scientific method, they are not considered science until they can be proven by objective evidence. |

'''Pseudoscience''' is any kind of knowledge, belief, or practice that claims to be scientific but does not follow the [[scientific method]].<ref>"''Pseudoscientific - pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific''", from the ''Oxford American Dictionary'', published by the [[Oxford English Dictionary]].</ref> Pseudosciences may appear scientific, but they do not adhere to the basic requirements (the testability and repeatability) of the scientific method. As such, since these practices are not proven by the scientific method, they are not considered science until they can be proven by objective evidence. |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

On occasion, attempts to create scientific support for various religious, or ideological beliefs, has resulted in forms of pseudoscience being officially sanctioned by church or state authorities. Examples include the race theories of [[Nazi Germany]], the [[Lysenkoism]] of [[Stalin]]ist [[Russian History|Russia]] and theories such as [[Creation Science]] and [[Intelligent Design]] of certain [[Fundamentalist Christian]] groups. |

On occasion, attempts to create scientific support for various religious, or ideological beliefs, has resulted in forms of pseudoscience being officially sanctioned by church or state authorities. Examples include the race theories of [[Nazi Germany]], the [[Lysenkoism]] of [[Stalin]]ist [[Russian History|Russia]] and theories such as [[Creation Science]] and [[Intelligent Design]] of certain [[Fundamentalist Christian]] groups. |

||

==Psychology== |

==Pseudoscience in Clincal Psychology== |

||

{{npov}} |

|||

Neurologists and clinical psychologists are concerned about the increasing amount of what they consider pseudoscience promoted in [[psychotherapy]] and popular [[psychology]], and also about what they see as pseudoscientific therapies such as [[Neuro-linguistic programming]], [[EMDR]], [[Rebirthing]], Reparenting, and [[Primal Therapy]] being adopted by government and professional bodies and by the public.<ref> e.g. Drenth (2003) [http://www.drexel.edu/coas/psychology/papers/herbertscience.pdf]; Herbert JD, ''et al.'' (2000) Science and pseudoscience in the development of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: implications for clinical psychology. ''Clin Psychol Rev.'' 20:945-71 [PMID 11098395])</ref> They state that scientifically unsupported therapies used by popular or folk psychology might harm vulnerable members of the public, undermine legitimate therapies, and tend to spread misconceptions about the nature of the mind and brain to society at large. Norcross ''et al''.<ref>Norcross J.C. Garofalo. A. Koocher.G.P. (2006) Discredited psychological treatments and tests: a Delphi poll. ''Professional Psychology. Research and Practice'', 37: 515-522.</ref> have approached the science/pseudoscience issue by conducting a survey of experts that seeks to specify which theory or therapy is considered to be definitely discredited, and they outline 14 fields that have been definitely discredited. |

Neurologists and clinical psychologists are concerned about the increasing amount of what they consider pseudoscience promoted in [[psychotherapy]] and popular [[psychology]], and also about what they see as pseudoscientific therapies such as [[Neuro-linguistic programming]], [[EMDR]], [[Rebirthing]], Reparenting, and [[Primal Therapy]] being adopted by government and professional bodies and by the public.<ref> e.g. Drenth (2003) [http://www.drexel.edu/coas/psychology/papers/herbertscience.pdf]; Herbert JD, ''et al.'' (2000) Science and pseudoscience in the development of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: implications for clinical psychology. ''Clin Psychol Rev.'' 20:945-71 [PMID 11098395])</ref> They state that scientifically unsupported therapies used by popular or folk psychology might harm vulnerable members of the public, undermine legitimate therapies, and tend to spread misconceptions about the nature of the mind and brain to society at large. Norcross ''et al''.<ref>Norcross J.C. Garofalo. A. Koocher.G.P. (2006) Discredited psychological treatments and tests: a Delphi poll. ''Professional Psychology. Research and Practice'', 37: 515-522.</ref> have approached the science/pseudoscience issue by conducting a survey of experts that seeks to specify which theory or therapy is considered to be definitely discredited, and they outline 14 fields that have been definitely discredited. |

||

Revision as of 06:31, 21 June 2007

Pseudoscience is any kind of knowledge, belief, or practice that claims to be scientific but does not follow the scientific method.[1] Pseudosciences may appear scientific, but they do not adhere to the basic requirements (the testability and repeatability) of the scientific method. As such, since these practices are not proven by the scientific method, they are not considered science until they can be proven by objective evidence.

The term pseudoscience appears to have been first used in 1843[2] as a combination of the Greek root pseudo, meaning false, and the Latin scientia, meaning knowledge or a field of knowledge. The term has negative connotations, because it is used to indicate that subjects so labeled are inaccurately or deceptively portrayed as science.[3] Accordingly, those labeled as practicing or advocating a "pseudoscience" normally reject this classification.

As it is taught in certain introductory science classes, pseudoscience is any subject that appears superficially to be scientific or whose proponents state is scientific but nevertheless substantially deviates from fundamental aspects of the scientific method.[4] Professor Paul DeHart Hurd[5] argued that a large part of gaining scientific literacy is being able to distinguish science from pseudo-science such as astrology, eugenics, quackery, the occult, and superstition.[6] Certain introductory survey classes in science take careful pains to delineate the objections scientists and skeptics have to practices that make direct claims contradicted by the scientific discipline in question.[7]

Beyond the initial introductory analyses offered in science classes, there is some epistemological disagreement about whether it is possible to distinguish "science" from "pseudoscience" in a reliable and objective way.[8]

Pseudosciences may be characterised by the use of vague, exaggerated or untestable claims, over-reliance on confirmation rather than refutation, lack of openness to testing by other experts, and a lack of progress in theory development.

Background

The standards for determining whether a body of knowledge, methodology, or practice is scientific can vary from field to field, but involve agreed principles including reproducibility and intersubjective verifiability.[9] Such principles aim to ensure that relevant evidence can be reproduced and/or measured given the same conditions, which allows further investigation to determine whether a hypothesis or theory related to given phenomena is both valid and reliable for use by others, including other scientists and researchers. It is expected that the scientific method will be applied throughout, and that bias will be controlled or eliminated, by double-blind studies, or statistically through fair sampling procedures. All gathered data, including experimental/environmental conditions, are expected to be documented for scrutiny and made available for peer review, thereby allowing further experiments or studies to be conducted to confirm or falsify results, as well as to determine other important factors such as statistical significance, confidence intervals, and margins of error.[10] Fulfillment of these requirements allows others a reasonable opportunity to assess whether to rely upon the reported results in their own scientific work or in a particular field of applied science, technology, therapy, or other form of practice.

In the mid-20th Century Karl Popper suggested the criterion of falsifiability to distinguish science from non-science.[11] Statements such as "God created the universe" may be true or false, but they are not falsifiable, so they are not scientific; they lie outside the scope of science. Popper subdivided non-science into philosophical, mathematical, mythological, religious and/or metaphysical formulations on the one hand, and pseudoscientific formulations on the other—though without providing clear criteria for the differences.[12] He gave astrology, Freud's psychoanalysis and Alder's individual psychology as good examples of pseudoscience, and Einstein's theory of relativity as an example of science.[13] More recently, Paul Thagard (1978) proposed that pseudoscience is primarily distinguishable from science when it is less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and the selective and or lack of attempts by proponents to solve problems with the theory.[citation needed] Mario Bunge (1984) has suggested the categories of "belief fields" and "research fields" to help distinguish between science and pseudoscience.[citation needed]

Philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend has argued, from a sociology of knowledge perspective, that a distinction between science and non-science is neither possible nor desirable.[14][15] Among the issues which can make the distinction difficult are that both the theories and methodologies of science evolve at differing rates in response to new data.[16] In addition, the specific standards applicable to one field of science may not be those employed in other fields. Thagard (1978) also writes from a sociological perspective and states that "elucidation of how science differs from pseudoscience is the philosophical side of an attempt to overcome public neglect of genuine science."

Both the skeptics and the brights movement, most prominently represented by Richard Dawkins, Mario Bunge, Carl Sagan and James Randi, consider all forms of pseudoscience to be harmful, whether or not they result in immediate harm to their adherents. These critics generally consider that the practice of pseudoscience may occur for a number of reasons, ranging from simple naïveté about the nature of science and the scientific method, to deliberate deception for financial or political gain. At the extreme, issues of personal health and safety may be very directly involved, for example in the case of physical or mental therapy or treatment, or in assessing safety risks. In such instances the potential for direct harm to patients, clients, the general public, or the environment may be an issue in assessing pseudoscience. (See also Junk science.)

The concept of pseudoscience as antagonistic to bona fide science appears to have emerged in the mid-19th century. Among the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles".

Identifying pseudoscience

A field, practice, or body of knowledge might reasonably be called pseudoscientific when (1) it is presented as consistent with the accepted norms of scientific research; but (2) it demonstrably fails to meet these norms, most importantly, in misuse of scientific method.[17]

Subjects may be considered pseudoscientific for various reasons; Popper considered astrology to be pseudoscientific simply because astrologers keep their claims so vague that they could never be refuted, whereas Thagard considers astrology pseudoscientific because its practitioners make little effort to develop the theory, show no concern for attempts to critically evaluate the theory in relation to others, and are selective in considering evidence. More generally, Thagard stated that pseudoscience tends to focus on resemblances rather than cause-effect relations.

Science is also distinguishable from revelation, theology, or spirituality in that it claims to offer insight into the physical world obtained by "scientific" means. Systems of thought that derive from divine or inspired knowledge are not considered pseudoscience if they do not claim either to be scientific or to overturn well-established science.

Some statements and commonly held beliefs in popular science may not meet the criteria of science. "Pop" science may blur the divide between science and pseudoscience among the general public, and may also involve science fiction.[18] Indeed, pop science is disseminated to, and can also easily emanate from, persons not accountable to scientific methodology and expert peer review.

The following have been proposed to be indicators of poor scientific reasoning.

Use of vague, exaggerated or untestable claims

- Assertion of scientific claims that are vague rather than precise, and that lack specific measurements.[19]

- Failure to make use of operational definitions. (i.e. a scientific description of the operational means in which a range of numeric measurements can be obtained).[20]

- Failure to make reasonable use of the principle of parsimony, i.e. failing to seek an explanation that requires the fewest possible additional assumptions when multiple viable explanations are possible (see: Occam's Razor)[21]

- Use of obscurantist language, and misuse of apparently technical jargon in an effort to give claims the superficial trappings of science.

- Lack of boundary conditions: Most well-supported scientific theories possess boundary conditions (well articulated limitations) under which the predicted phenomena do and do not apply.[22]

Over-reliance on confirmation rather than refutation

- Assertion of scientific claims that cannot be falsified in the event they are incorrect, inaccurate, or irrelevant (see also: falsifiability)[23]

- Assertion of claims that a theory predicts something that it has not been shown to predict[24]

- Assertion that claims which have not been proven false must be true, and vice versa (see: Argument from ignorance)[25]

- Over-reliance on testimonials and anecdotes. Testimonial and anecdotal evidence can be useful for discovery (i.e. hypothesis generation) but should not be used in the context of justification (i.e. hypothesis testing).[26]

- Selective use of experimental evidence: presentation of data that seems to support its own claims while suppressing or refusing to consider data that conflict with its claims.[27]

- Reversed burden of proof. In science, the burden of proof rests on the individual making a claim, not on the critic. "Pseudoscientific" arguments may neglect this principle and demand that skeptics demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that a claim (e.g. an assertion regarding the efficacy of a novel therapeutic technique) is false. It is essentially impossible to prove a universal negative, so this tactic incorrectly places the burden of proof on the skeptic rather than the claimant.[28]

- Appeals to holism: Proponents of pseudoscientific claims, especially in organic medicine, alternative medicine, naturopathy and mental health, often resort to the “mantra of holism” to explain negative findings.[29]

Lack of openness to testing by other experts

- Evasion of peer review before publicizing results (called "science by press conference").[30] Some proponents of theories that contradict accepted scientific theories avoid subjecting their work to the often ego-bruising process of peer review, sometimes on the grounds that peer review is inherently biased against claims that contradict established paradigms, and sometimes on the grounds that assertions cannot be evaluated adequately using standard scientific methods. By remaining insulated from the peer review process, these proponents forego the opportunity of corrective feedback from informed colleagues.[31]

- The science community expects authors to share data necessary to evaluate a paper. Failure to provide adequate information for other researchers to reproduce the claimed results is a lack of openness.[32]

- Assertion of claims of secrecy or proprietary knowledge in response to requests for review of data or methodology.[33]

Lack of progress

- Failure to progress towards additional evidence of its claims.[34] Terrence Hines has identified astrology as a subject that has changed very little in the past two millennia.[35]

- Lack of self correction: scientific research programmes make mistakes, but they tend to eliminate these errors over time.[36] By contrast, theories may be accused of being pseudoscientific because they have remained unaltered despite contradictory evidence.[37]

Personalization of issues

- Tight social groups and granfalloons. Authoritarian personality, suppression of dissent, and groupthink can enhance the adoption of beliefs that have no rational basis. In attempting to confirm their (confirmation bias), the group tends to identify their critics as enemies.[38]

- Assertion of claims of a conspiracy on the part of the scientific community to suppress the results.[39]

- Attacking the motives or character of anyone who questions the claims (see Ad hominem fallacy).[38]

Demographics

The National Science Foundation stated that, in the USA, "pseudoscientific" beliefs became more widespread during the 1990s, peaked near 2001 and mildly declined since; nevertheless, pseudoscientific beliefs remain common in the USA.[40] As a result, according to the NSF report, there is a lack of knowledge of pseudoscientific issues in society and pseudoscientific practices are commonly followed. Bunge (1999) states that "A survey on public knowledge of science in the United States showed that in 1988 50% of American adults [rejected] evolution, and 88% [believed] astrology is a science'".

Commentators on pseudoscience perceive it in many fields; for example Pseudomathematics is a term used for mathematics-like activity undertaken either by non-mathematicians or mathematicians themselves which does not conform to the rigorous standards usually applied to mathematical theorems.

Religion and Ideology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

On occasion, attempts to create scientific support for various religious, or ideological beliefs, has resulted in forms of pseudoscience being officially sanctioned by church or state authorities. Examples include the race theories of Nazi Germany, the Lysenkoism of Stalinist Russia and theories such as Creation Science and Intelligent Design of certain Fundamentalist Christian groups.

Pseudoscience in Clincal Psychology

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Neurologists and clinical psychologists are concerned about the increasing amount of what they consider pseudoscience promoted in psychotherapy and popular psychology, and also about what they see as pseudoscientific therapies such as Neuro-linguistic programming, EMDR, Rebirthing, Reparenting, and Primal Therapy being adopted by government and professional bodies and by the public.[41] They state that scientifically unsupported therapies used by popular or folk psychology might harm vulnerable members of the public, undermine legitimate therapies, and tend to spread misconceptions about the nature of the mind and brain to society at large. Norcross et al.[42] have approached the science/pseudoscience issue by conducting a survey of experts that seeks to specify which theory or therapy is considered to be definitely discredited, and they outline 14 fields that have been definitely discredited.

A typical concept used in some fringe psychotherapies is orgone energy. "There is an increasing degree of overlapping and blending of orgone therapy with New Age and other therapies that manipulate the patient’s biofields, such as Therapeutic Touch and Reiki. 'Biofield' is a pseudoscientific term often used synonymously with orgone energy. Klee states that there is even small minority of psychiatrists that promote orgone therapy, though such organizations are frowned upon by the general psychiatric community.[43]

But there is also grave concern that a rush to evidence-based practice in psychology will ignore the evidentiary validity of the clinicians observations as well as ignoring the fact that neither research nor clinical practice are theory-free. And at this point in history there is no single model or theory in the body of knowledge we call psychology.[44] This, combined with the subjective nature of the phenomena under study makes it more difficult to separate out bad theories attempting to explain actual results from bad theories claiming results that don't exist.

Medicine and health care

Shark cartilage is falsely promoted as a cancer cure on the basis of an alleged lack of cancer in sharks. According to Ostrander et al (2004) this practice has led to a continuing decline in shark populations, and, perhaps more importantly, patients have been diverted from otherwise effective cancer treatment.[45] They suggest that "the evidence-based mechanisms of evaluation used daily by the formal scientific community should be added to the training of media and governmental professionals".

Psychological explanations

Pseudoscientific thinking has been explained in terms of psychology and social psychology. The human proclivity for seeking confirmation rather than refutation (confirmation bias),[46] the tendency to hold comforting beliefs, and the tendency to overgeneralize have been proposed as reasons for the common adherence to pseudoscientific thinking. According to Beyerstein (1991) humans are prone to associations based on resemblances only, and often prone to misattribution in cause-effect thinking.

The transition from pseudoscience to science

There are examples of presently accepted scientific theories that were once criticised by some as being pseudoscientific. The transition is marked by increasingly scientific scrutiny and specificity within the field and an increased level of evidence to support the theory. Continental drift theory was once considered pseudoscientific (Williams 2000:58), but is now part of mainstream science especially since the paleomagnetic evidence was discovered that supported plate tectonics.

Fields can also repudiate notions that some consider to be pseudoscientific in favour of more conventional element(s) of their field. For example, Atwood (2004) suggested that "osteopathy has, for the most part, repudiated its pseudoscientific beginnings and joined the world of rational healthcare."[47]

At times, scientists use the descriptor "pseudoscience" to distinguish between even mainstream investigations of varying rigor. As observational evidence and theoretical descriptions improve and fields develop, disciplines criticized for having pseudoscientific aspects may become more respected by the scientific community. The field of physical cosmology has had such a history.[48] Currently, string theory has been criticized by certain researchers as suffering from the same problems[49]

Criticisms of the concept of pseudoscience

Pseudoscience contrasted with protoscience

Some criticisms that lead to the accusation of pseudoscience are also true to some extent of some new genuinely scientific work. These include:

- claims or theories unconnected to previous experimental results

- claims which contradict experimentally established results

- work failing to operate on standard definitions of concepts

- emotion-based resistance, by the scientific community, to new claims or theories[50]

Protoscience is a term sometimes used to describe a hypothesis that has not yet been adequately tested by the scientific method, but which is otherwise consistent with existing science or which, where inconsistent, offers reasonable account of the inconsistency. It may also describe the transition from a body of practical knowledge into a scientific field.[51] By contrast, "pseudoscience" is reserved to describe theories which are either untestable in practice or in principle, or which are maintained even when tests appear to have refuted them.

It is widely disputed (notably by Feyeraband, see above) whether any clear or meaningful boundaries can be drawn between pseudoscience, protoscience, and "real" science. Especially where there is a significant cultural or historical distance (as, for example, modern chemistry reflecting on alchemy), protosciences can be misinterpreted as pseudoscientific. Many people have tried to offer objective distinctions, with mixed success.

If the claims of a given field can be experimentally tested and methodological standards are upheld, it is not "pseudoscience", however odd, astonishing, or counter-intuitive. If claims made are inconsistent with existing experimental results or established theory, but the methodology is sound, caution should be used; much of science consists of testing hypotheses that turn out to be false. In such a case, the work may be better described as ideas that are not yet generally accepted. Conversely, if the claims of any given "science" cannot be experimentally tested or scientific standards are not upheld in these tests, it fails to meet the modern criteria for a science.

Demarcation problem

After over a century of dialogue among philosophers of science and scientists in varied fields, and despite broad agreement on the basics of scientific method,[52] the boundaries between science and non-science continue to be debated.[53] This is known as the problem of demarcation.

Many commentators and practitioners of science, as well as supporters of fields of inquiry and practices labeled as pseudoscience, question the rigor of the demarcation[citation needed], as some disciplines now accepted as science previously had features cited as those of pseudoscience, such as lack of reproducibility, or the inability to create falsifiable experiments.[citation needed]

It has been argued by several notable commentators that experimental verification is not in itself decisive in scientific method. Thomas Kuhn states that in neither Popper's nor his own theory "can testing play a quite decisive role."[54] Daniel Rothbart said that "the defining feature of science does not seem to be experimental success, for most clear cases of genuine science have been experimentally falsified."[55] The latter proposed that a scientific theory must "account for all the phenomena that its rival background theory explains" and "must clash empirically with its rival by yielding test implications that are inconsistent with the rival theory". A theory is thus scientific or not depending upon its historical situation; if it betters the current explanations of phenomena, it marks scientific progress. "Many domains in ancient Greece, for example, domains that today are called superstition, religion, magic and the occult, were at that time clear cases of legitimate science." This is an explicitly competitive model of scientific work; Rothbart also notes that it is not a completely effective model.[56]

Kuhn postulated that proponents of competing paradigms may resort to political means (such as invective) to garner support from a public which lacks the ability to judge competing scientific theories on their merits. Philosopher of science Larry Laudan has suggested that pseudoscience has no scientific meaning and mostly describes our emotions: "If we would stand up and be counted on the side of reason, we ought to drop terms like ‘pseudo-science’ and ‘unscientific’ from our vocabulary; they are just hollow phrases which do only emotive work for us".[57] Richard McNally, Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, states: "The term 'pseudoscience' has become little more than an inflammatory buzzword for quickly dismissing one’s opponents in media sound-bites" and "When therapeutic entrepreneurs make claims on behalf of their interventions, we should not waste our time trying to determine whether their interventions qualify as pseudoscientific. Rather, we should ask them: How do you know that your intervention works? What is your evidence?".[58]

See also

- Bad science

- Cargo cult science

- Committee for Skeptical Inquiry aka. CSICOP

- Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, a book by Dr William F. Williams

- The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience edited by Michael Shermer of The Skeptics Society

- Junk science

- Paradigm shift

- Pathological science

- Paranormal

- Parapsychology

- Protoscience

- Pseudohistory

- Pseudoskepticism (or Pathological skepticism)

- Quackery

- True-believer syndrome

Lists

- Crank (article which contains a list of theories)

- List of misconceptions

- List of pseudosciences and pseudoscientific concepts

References

- ^ "Pseudoscientific - pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific", from the Oxford American Dictionary, published by the Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Magendie, F (1843) An Elementary Treatise on Human Physiology. 5th Ed. Tr. John Revere. New York: Harper, p 150. Magendie refers to phrenology as "a pseudo-science of the present day" (note the hyphen).

- ^ However, from the "them vs. us" polarization that its usage engenders, the term may also have a positive function because "[the] derogatory labeling of others often includes an unstated self-definition "(p.266); and, from this, the application of the term also implies "a unity of science, a privileged tree of knowledge or space from which the pseudoscience is excluded, and the user's right to belong is asserted " (p.286) -- Still A & Dryden W (2004) "The Social Psychology of "Pseudoscience": A Brief History", J Theory Social Behav 34:265-290

- ^ For example, Hewitt et al. Conceptual Physical Science Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 18, 2003) ISBN 0-321-05173-4, Bennett et al. The Cosmic Perspective 3e Addison Wesley; 3 edition (July 25, 2003) ISBN 0-8053-8738-2

- ^ Memorial Resolution: Paul DeHart Hurd. www-sul.stanford.edu/depts/cubberley/collections/memorial.html retrieved 6 November. 2006

- ^ Hurd, P. D. (1998). "Scientific literacy: New minds for a changing world". Science Education, 82, 407–416.. Abstract online at www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/abstract/32148/ABSTRACT; retrieved 6 November. 2006

- ^ For example, consider this introductory course offered at the University of Maryland entitled "Science & Pseudoscience" [1]

- ^ The philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend in particular is associated with the view that attempts to distinguish science from non-science are flawed and pernicious. "The idea that science can, and should, be run according to fixed and universal rules, is both unrealistic and pernicious. ... the idea is detrimental to science, for it neglects the complex physical and historical conditions which influence scientific change. It makes our science less adaptable and more dogmatic:"[2]

- ^ e.g. Gauch HG Jr. Scientific Method in Practice (2003) 3-5 ff

- ^ Gauch (2003), 191 ff, especially Chapter 6, "Probability", and Chapter 7, "inductive Logic and Statistics"

- ^ Popper, KR (1959) "The Logic of Scientific Discovery" (English translation, 1959)[3].

- ^ Popper KR "Science: Conjectures and Refutations", reprinted in Grim P (1990) Philosophy of Science and the Occult, Albany, pp. 104-110

- ^ Popper KR (1962) Science, Pseudo-Science, and Falsifiability. Conjectures and Refutations

- ^ Feyerabend P Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge (1975)[4]

- ^ For a perspective on Feyerabend from within the scientific community, see, e.g., Gauch (2003) at p.4: "Such critiques are unfamiliar to most scientists, although some may have heard a few distant shots from the so-called science wars."

- ^ Thagard PR (1978) "Why astrology is a pseudoscience" (1978) In PSA 1978, Volume 1, ed. Asquith PD and Hacking I (East Lansing: Philosophy of Science Association, 1978) 223 ff. Thagard writes, at 227, 228: "We can now propose the following principle of demarcation: A theory or discipline which purports to be scientific is pseudoscientific if and only if: it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and non confirmations."

- ^ Cover JA, Curd M (Eds, 1998) Philosophy of Science: The Central Issues, 1-82

- ^ [5]

- ^ e.g. Gauch (2003) op cit at 211 ff (Probability, "Common Blunders")

- ^ Paul Montgomery Churchland, Matter and Consciousness: A Contemporary Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind (1999) MIT Press. p.90. "Most terms in theoretical physics, for example, do not enjoy at least some distinct connections with observables, but not of the simple sort that would permit operational definitions in terms of these observables. [..] If a restriction in favor of operational definitions were to be followed, therefore, most of theoretical physics would have to be dismissed as meaningless pseudoscience!"

- ^ Gauch HG Jr. (2003) op cit 269 ff, "Parsimony and Efficiency"

- ^ Hines T (1988) Pseudoscience and the Paranormal: A Critical Examination of the Evidence Buffalo NY: Prometheus Books. A Skeptical Inquirer Reader

- ^ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes." in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge pp 91-195; Popper KR (1959) The Logic of Scientific Discovery

- ^ e.g. Gauch (2003) op cit at 178 ff (Deductive Logic, "Fallacies"), and at 211 ff (Probability, "Common Blunders"). e.g. [6] Macmilllan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Vol 3, "Fallacies" 174 'ff, esp. section on "Ignoratio elenchi"

- ^ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy Vol 3, "Fallacies" 174 'ff esp. 177-178

- ^ Bunge M (1983) Demarcating science from pseudoscience Fundamenta Scientiae 3:369-388, 381

- ^ Thagard (1978)op cit at 227, 228

- ^ Lilienfeld SO (2004) Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology Guildford Press (2004) ISBN 1-59385-070-0

- ^ Ruscio J (2001) Clear thinking with psychology: Separating sense from nonsense, Pacific Grove, CA: Wadsworth

- ^ Peer review and the acceptance of new scientific ideas (Warning 469 kB PDF)*Peer review – process, perspectives and the path ahead; Lilienfeld (2004) op cit For an opposing perspective, e.g. Peer Review as Scholarly Conformity

- ^ Ruscio (2001) op cit.

- ^ Gauch (2003) op cit 124 ff"

- ^ Gauch (2003) op cit 124 ff"

- ^ Lakatos I (1970) "Falsification and the Methodology of Scientific Research Programmes." in Lakatos I, Musgrave A (eds.) Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge 91-195; Thagard (1978) op cit writes: "We can now propose the following principle of demarcation: A theory or discipline which purports to be scientific is pseudoscientific if and only if: it has been less progressive than alternative theories over a long period of time, and faces many unsolved problems; but the community of practitioners makes little attempt to develop the theory towards solutions of the problems, shows no concern for attempts to evaluate the theory in relation to others, and is selective in considering confirmations and disconfirmations."

- ^ Hines T, Pseudoscience and the Paranormal: A Critical Examination of the Evidence, Prometheus Books, Buffalo, NY, 1988. ISBN 0-87975-419-2. Thagard (1978) op cit 223 ff

- ^ name=Ruscio120>Ruscio J (2001) op cit. p120

- ^ The work Scientists Confront Velikovsky (1976) Cornell University, also delves into these features in some detail, as does the work of Thomas Kuhn, e.g. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) which also discusses some of the items on the list of characteristics of pseudoscience.

- ^ a b Devilly GJ (2005) Power therapies and possible threats to the science of psychology and psychiatry Austral NZ J Psych 39:437-445(9) Cite error: The named reference "Devilly" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ e.g. archivefreedom.org which claims that "The list of suppressed scientists even includes Nobel Laureates!"

- ^ [7] National Science Board. 2006. Science and Engineering Indicators 2006 Two volumes. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation (volume 1, NSB-06-01; NSB 06-01A)

- ^ e.g. Drenth (2003) [8]; Herbert JD, et al. (2000) Science and pseudoscience in the development of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: implications for clinical psychology. Clin Psychol Rev. 20:945-71 [PMID 11098395])

- ^ Norcross J.C. Garofalo. A. Koocher.G.P. (2006) Discredited psychological treatments and tests: a Delphi poll. Professional Psychology. Research and Practice, 37: 515-522.

- ^ Klee GD (2005) The Resurrection of Wilhelm Reich and Orgone Therapy The Scientific Review of Mental Health Practice (Vol. 4, No. 1)" | available online

- ^ Gerald C. Davison, PhD, President of the American Psychological Association's Clinical Psychology Division [9];Davidson is reporting to the APA's clinical members on the Presidential Task Force's report on Evidence-Based Practices in Psychology (EBPP).

- ^ Ostrander GK et al. (2004) Shark cartilage, cancer and the growing threat of pseudoscience. Cancer Res64:8485-91. Erratum in: Cancer Res. 65:374. PMID 15574750

- ^ (Devilly 2005:439)

- ^ Atwood KC (2004) Naturopathy, pseudoscience, and medicine: myths and fallacies vs truth. Medscape Gen Med6:e53 available online

- ^ Stephen W. Hawking, Hawking on the Big Bang and Black Holes (1993) World Scientific Publishing Company, Page 1 See also [10] and [11].

- ^ For example: Smolin L The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next. Houghton Mifflin Company. (2006) ISBN 0-618-55105-0

- ^ Kuhn TS (1962) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

- ^ Popper KR op. cit.

- ^ Gauch HG Jr (2003)op cit 3-7.

- ^ Cover JA, Curd M (Eds, 1998) Philosophy of Science: The Central Issues, 1-82

- ^ Kuhn TS "Logic of Discovery or Psychology of Research?" in Grim, op. cit. p. 125

- ^ Rothbart D "Demarcating Genuine Science from Pseudoscience", in Grim, op. cit. pp.114.

- ^ Rothbart, Daniel, op. cit. pp. 114-20.

- ^ Laudan L (1996) "The demise of the demarcation problem" in Ruse, Michael, But Is It Science?: The Philosophical Question in the Creation/Evolution Controversy pp. 337-350.

- ^ McNally RJ (2003) Is the pseudoscience concept useful for clinical psychology? SRMHP Vol 2 Number 2 Fall/Winter[12]

Literature

- Bauer, Henry H. (2000) Science or Pseudoscience University of Illinois Press

- Beyerstein BL (1990) Brainscams: Neuromythologies of the New Age. Int'l. J. of Mental Health, 19(3):27-36.[13]

- Georges Charpak (2004) Debunked!, Johns Hopkins University Press [ISBN 0-8018-7867-5]

- Derksen, AA, (1993) The seven sins of pseudo-science J Gen Phil Sci 24:17-42. [14]

- Derksen AA (2001) The seven strategies of the sophisticated pseudo-scientist: a look into Freud's rhetorical toolbox,J Gen Phil Sci 32:329-50

- Gardner M (1983) Science – Good, Bad and Bogus Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Gauch Jr Hugh G (2002) Scientific Method in Practice, Cambridge University Press [ISBN-13 978-0521017084]

- Hansson SO (1996) Defining pseudoscience Philosophia naturalis 33:169-76

- Joseph J (2002) Twin studies in psychiatry and psychology: science or pseudoscience? Psychiatric Quarterly 73:71-82[15]

- Martin M (1994) Pseudoscience, the paranormal, and science education Science & Education 3:1573-901 [16]

- Ostrander.G.K, Cheng,K.C, Wolf.J.C. WolfeM.J. Shark Cartilage, Cancer and the Growing Threat of Pseudoscience. Cancer Research 64, 8485-8491, December 1, 2004

- Sampson W, Beyerstein BL (1996) Traditional medicine and pseudoscience in China Skeptical Inquirer Sept-Oct

- Sagan, Carl (1996) The Demon-Haunted World: Science As a Candle In the Dark

- Shermer M (2002) Why People Believe Weird Things – Pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time New York

- Wilson F (2000) The Logic and Methodology of Science and Pseudoscience, Canadian Scholars Press [ISBN 1-55130-175-X]

External links

- Checklist for identifying dubious technical processes and products - Rainer Bunge, PhD

- The Anatomy of Pseudoscience - Steven Novella, MD

- Debating pseudoscientists - Philip Plait

- Distinguishing Science from Pseudoscience - Rory Coker, PhD

- Distinguishing Science from Pseudoscience - Barry L. Beyerstein

- Pseudoscience - Robert Todd Carroll, PhD

- Pseudoscience. What is it? How can I recognize it? - Stephen Lower

- Science and Pseudoscience - transcript and broadcast of talk by Imre Lakatos

- Science Needs to Combat Pseudoscience - A statement by 32 Russian scientists and philosophers

- Science, Pseudoscience, and Irrationalism - Steven Dutch

- The Seven Warning Signs of Bogus Science - Robert L. Park

- Why Is Pseudoscience Dangerous? - Edward Kruglyakov

- Plate Tectonics: The Rocky History of an Idea by Brian Simison, University of California, Berekley, Museum of Palenotology, retrieved August 2, 2006