Soap: Difference between revisions

→Lye: Format |

→Soapmaking: Arranged descriptions into coherent subcategories. |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

The hydrocarbon ("fatty") portion dissolves dirt and oils, while the ionic end makes it soluble in water. Therefore, it allows water to remove normally-insoluble matter by [[emulsification]]. |

The hydrocarbon ("fatty") portion dissolves dirt and oils, while the ionic end makes it soluble in water. Therefore, it allows water to remove normally-insoluble matter by [[emulsification]]. |

||

== |

==Soap Making== |

||

[[Image:Soap%20P1140887.jpg|thumb|Handmade soaps sold at a shop in [[Hyères]], [[France]]]] |

[[Image:Soap%20P1140887.jpg|thumb|Handmade soaps sold at a shop in [[Hyères]], [[France]]]] |

||

The most |

The most common soap making process today is the cold process method, where fats such as [[olive oil]] react with [[Sodium Hydroxide|lye]]. Soap makers sometimes use the [[melt and pour]] process, where a premade soap base is melted and poured in individual molds. While some people think that this is not really soap making, the [[Hand Crafted Soap Makers Guild]] does recognize this as a legitimate form of soap crafting. Some [[soaper]]s also practice other processes, such as the historical hot process, and make special soaps such as clear or transparent soap, which must be made with [[ethanol]] or [[isoproply alcohol]].<ref>Failor, Catherine (2000).</ref> |

||

Handmade soap differs from industrial soap in that whole oils containing intact [[triglycerides]] are used and [[glycerin]] is a desireable byproduct. Industrial detergent manufacturers commonly use fatty acids, which are detached from the gylcerol heads found in triglycerides. Without the glycerol heads, the detached fatty acids do not yield glyerin as a byproduct. |

Handmade soap differs from industrial soap in that whole oils containing intact [[triglycerides]] are used and [[glycerin]] is a desireable byproduct. Industrial detergent manufacturers commonly use fatty acids, which are detached from the gylcerol heads found in triglycerides. Without the glycerol heads, the detached fatty acids do not yield glyerin as a byproduct.<ref>http://www.pallasathenesoap.com/trivia.html Pallas Athene Soap</ref> |

||

===[[Lye]]=== |

===[[Lye]]=== |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

===Fat=== |

===Fat=== |

||

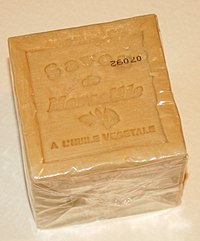

[[Image:Savon de Marseille.jpg|thumb|200px|Handicraft made [[Marseille soap]]]] |

[[Image:Savon de Marseille.jpg|thumb|200px|Handicraft made [[Marseille soap]]]] |

||

Soap is |

Soap is made from either vegetable or animal fats. [[Sodium tallowate]], a fatty acid sometimes used to make soaps, is derived from tallow, which is [[Kitchen rendering|rendered]] from cattle or sheep tissue. Soap can also be made of vegetable oils, such as [[palm oil]], [[olive oil]], or [[coconut oil]]. If soap is made from pure [[olive oil]] it may be called [[Castile soap]] or [[Marseille soap]]. Castile is also sometimes applied to soaps with a mix of oils, but a high percentage of olive oil. |

||

An array of oils and butters are used in the process such as olive, coconut, palm, cocoa butter, [[hemp oil]] and shea butter to provide different qualities. |

An array of oils and butters are used in the process such as [[olive oil]], [[coconut oil]], [[palm oil]], cocoa butter, [[hemp oil]] and [[shea butter]] to provide different qualities. For example, olive oil provides mildness in soap; coconut oil provides lots of lather; while coconut and palm oils provide hardness. Most common, is a combination of coconut, palm, and olive oils. |

||

===Process=== |

===Process=== |

||

Cold process soap making is done without heating the soap batter, while hot process soap making requires that the soap batter be heated. Both processes are described after the general soap making process description. |

|||

In both cold-process and hot-process soapmaking, heat may be required for [[saponification]]. |

|||

====General Soap Making Process==== |

|||

Cold-process soapmaking takes place at a temperature sufficiently above room temperature to ensure the [[melting|liquification]] of the fat being used, and requires that the lye and fat be kept warm after mixing to ensure that the soap is completely saponified. |

|||

Soap making requires using saponification charts<ref>http://www.certified-lye.com/lye-soap.html#LyeSoap Certified Lye</ref> to determine the exact measurement of [[lye]] and fat to ensure that all of the ingredients will successfully react with each other and that no free [[lye]] will remain in the soap.<ref>http://www.natural-soap-directory.com/soap-terms.html#make-soap Natural Soap Directory</ref> Excess unreacted [[lye]] in the soap will result in a very high [[pH]] and can burn or irritate skin. Not enough [[lye]] will result in greasy sludge that will not form solid bars of soap. |

|||

Some soap makers "superfat" their soap by adding 5-10% excess fats so that some oils will remain in the finished bars of soap. Likewise, other soap makers discount the formulated amount of [[lye]] to 90-95% and withhold some of the [[lye]] from the recipe to ensure that some free oils will remain in the finished bars of soap.<ref>http://www.natural-soap-directory.com/soap-terms.html Natural Soap Directory</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The [[lye]] is dissolved in water. Then oils are heated and liquify if they are solid at room temperature. Once fats and [[lye]] water have both cooled the same temperature and are 80-100° F, they are combined. This mixture of [[lye]] water and fats is stirred until "trace" occurs and the mixture becomes a soap batter. There are varying levels of trace: A light trace implies a thinner soap batter and a heavy trace implies a thicker soap batter. Additives, such as [[essential oil]]s, [[fragrance oil]]s, botanicals, clays, colorants or other fragrance materials, are combined with the soap batter at different degrees of trace, depending upon the additive. With elapsed time and continued agitation the soap batter will continue to thicken. The cold process soap batter is then poured into molds, while hot process soap batter is poured into a double boiler or crockpot to be heated. |

|||

Hot-process was used when the purity of lye was unreliable, and can use natural lye solutions such as [[potash]]. The main benefit of hot processing is that the exact concentration of the lye solution does not need to be known to perform the process with adequate success. |

|||

====Cold Process==== |

|||

Cold-process requires exact measurement of lye to fat using saponification charts to ensure that the finished product is mild and skin-friendly. Saponification charts can also be used in hot-process soapmaking, but are not as necessary as in cold-process. |

|||

Although cold-process soapmaking takes place at room temperature; first, the fats are heated to ensure the [[melting|liquification]] of the fats used. Then, when the [[lye]] water solution is added to the fats, it should be the same temperature of the melted oils and both are typically between 80-90° F. An external heat source is not necessary but the molded soap should be incubated by being wrapped in blankets or towels for 24 hours after being poured into the mold. Milk soaps are the exception. They do not require insulation. Insulation may cause the milk to sour. The soap will continue to exothermically give off heat for many hours after being molded. During this time, it is normal for the soap to go through a "gel phase" where the opaque soap will turn somewhat transparent for several hours before turning opaque again. The soap may be removed from the mold after 24 hours but the saponification process takes several weeks to be complete. |

|||

====Hot Process==== |

|||

| ⚫ | Unlike cold processed soap, all hot processed soap experiences a "gel phase" as a result of being heated, such as in a double boiler or crockpot. Hot process soap may used soon after being removed from the mold because [[lye]] and fat saponify more quickly at the higher temperatures used in hot process soap making. |

||

In the hot-process method, lye and [[fatty acid|fat]] are boiled together at 80–100 °C until saponification occurs, which the soapmaker can determine by taste (the bright, distinctive taste of lye disappears once all the lye is saponified) or by eye (the experienced eye can tell when gel stage and full saponification have occurred). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

After saponification has occurred, the soap is sometimes [[precipitation (chemistry)|precipitated]] from the solution by adding salt, and the excess liquid drained off. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

The hot, soft soap is then spooned into a mold. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

;Cold process |

|||

A cold-process soapmaker first looks up the saponification value of the fats being used on a saponification chart, which is then used to calculate the appropriate amount of lye. Excess unreacted lye in the soap will result in a very high pH and can burn or irritate skin. Not enough lye, and the soap is greasy. Most soap makers formulate their recipes with a 4-10% discount of lye so that all of the lye is reacted and that excess fat is left for skin conditioning benefits. |

|||

| ⚫ | Soap pellets are combined with fragrances and other materials and blended to homogeneity in an amalgamator (mixer). The mass is then discharged from the mixer into a refiner which, by means of an [[auger]], forces the soap through a fine wire screen. From the refiner the soap passes over a roller mill (French milling or hard milling) in a manner similar to [[calendering]] paper or plastic or to making [[chocolate liquor]]. The soap is then passed through one or more additional refiners to further plasticize the soap mass. Immediately before extrusion it passes through a vacuum chamber to remove any entrapped air. It is then extruded into a long log or blank, cut to convenient lengths, passed through a metal detector and then stamped into shape in refrigerated tools. The pressed bars are packaged in many ways.{{fact}} |

||

The lye is dissolved in water. Then oils are heated, or melted if they are solid at room temperature. Once both substances have cooled to approximately 100-110° F, and are no more than 10° F apart, they may be combined. This lye-fat mixture is stirred until "trace" (modern-day amateur soapmakers often use a stick blender to speed this process). There are varying levels of trace. Depending on how your additives will affect trace, they may be added at light trace, medium trace or heavy trace. After much stirring, the mixture turns to the consistency of a thin pudding. |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Sand]] or [[pumice]] may be added to produce a [[wiktionary:scouring|scouring]] soap. This process is most common in creating soaps used for human hygiene. The scouring agents serve to remove dead skin cells from the surface being cleaned. This process is called [[exfoliation (cosmetology)|exfoliation]]. Many newer materials are used for exfoliating soaps which are effective but do not have the sharp edges and poor size distribution of pumice.{{fact}} |

||

[[Essential oil]]s, [[fragrance oil]]s, botanicals, herbs, oatmeal or other additives are added at light trace, just as the mixture starts to thicken. |

|||

The batch is then poured into molds, kept warm with towels or blankets, and left to continue saponification for 18 to 48 hours. Milk soaps are the exception. They do not require insulation. Insulation may cause the milk to burn. During this time, it is normal for the soap to go through a "gel phase" where the opaque soap will turn somewhat transparent for several hours before turning opaque again. The soap will continue to give off heat for many hours after trace. |

|||

After the insulation period the soap is firm enough to be removed from the mold and cut into bars. At this time, it is safe to use the soap since saponification is complete. However, cold-process soaps are typically cured and hardened on a drying rack for 2-6 weeks (depending on initial water content) before use. If using caustic soda it is recommended that the soap is left to cure for at least 4 weeks. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Soap pellets are combined with fragrances and other materials and blended to homogeneity in an amalgamator (mixer). The mass is then discharged from the mixer into a refiner which, by means of an [[auger]], forces the soap through a fine wire screen. From the refiner the soap passes over a roller mill (French milling or hard milling) in a manner similar to [[calendering]] paper or plastic or to making [[chocolate liquor]]. The soap is then passed through one or more additional refiners to further plasticize the soap mass. Immediately before extrusion it passes through a vacuum chamber to remove any entrapped air. It is then extruded into a long log or blank, cut to convenient lengths, passed through a metal detector and then stamped into shape in refrigerated tools. The pressed bars are packaged in many ways. |

||

| ⚫ | [[Sand]] or [[pumice]] may be added to produce a [[wiktionary:scouring|scouring]] soap. This process is most common in creating soaps used for human hygiene. The scouring agents serve to remove dead skin cells from the surface being cleaned. This process is called [[exfoliation (cosmetology)|exfoliation]]. Many newer materials are used for exfoliating soaps which are effective but do not have the sharp edges and poor size distribution of pumice. |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Revision as of 05:16, 23 February 2008

Soap is a surfactant used in conjunction with water for washing and cleaning that historically comes in solid bars but also in the form of a thick liquid.

Historically, soap has been composed of sodium (soda ash) or potassium (potash) salts of fatty acids derived by reacting fat with lye in a process known as saponification. The fats are hydrolyzed by the base, yielding glycerol and crude soap.

Many cleaning agents today are technically not soaps, but detergents, which are less expensive and easier to manufacture.

How soap works

Soaps are useful for cleaning because soap molecules attach readily to both nonpolar molecules (such as grease or oil) and polar molecules (such as water). Although grease will normally adhere to skin or clothing, the soap molecules can attach to it as a "handle" and make it easier to rinse away. Applied to a soiled surface, soapy water effectively holds particles in suspension so the whole of it can be rinsed off with clean water.

(fatty end) :CH3-(CH2)n - CONa: (water soluble end)

The hydrocarbon ("fatty") portion dissolves dirt and oils, while the ionic end makes it soluble in water. Therefore, it allows water to remove normally-insoluble matter by emulsification.

Soap Making

The most common soap making process today is the cold process method, where fats such as olive oil react with lye. Soap makers sometimes use the melt and pour process, where a premade soap base is melted and poured in individual molds. While some people think that this is not really soap making, the Hand Crafted Soap Makers Guild does recognize this as a legitimate form of soap crafting. Some soapers also practice other processes, such as the historical hot process, and make special soaps such as clear or transparent soap, which must be made with ethanol or isoproply alcohol.[1]

Handmade soap differs from industrial soap in that whole oils containing intact triglycerides are used and glycerin is a desireable byproduct. Industrial detergent manufacturers commonly use fatty acids, which are detached from the gylcerol heads found in triglycerides. Without the glycerol heads, the detached fatty acids do not yield glyerin as a byproduct.[2]

Reacting fat with lye (sodium hydroxide) will produce a hard bar soap. Reacting fat with potassium hydroxide will produce a soap that is either soft or liquid. Historically, the alkalis used were sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and sodium carbonate leached from hardwood ashes.[3]

Fat

Soap is made from either vegetable or animal fats. Sodium tallowate, a fatty acid sometimes used to make soaps, is derived from tallow, which is rendered from cattle or sheep tissue. Soap can also be made of vegetable oils, such as palm oil, olive oil, or coconut oil. If soap is made from pure olive oil it may be called Castile soap or Marseille soap. Castile is also sometimes applied to soaps with a mix of oils, but a high percentage of olive oil.

An array of oils and butters are used in the process such as olive oil, coconut oil, palm oil, cocoa butter, hemp oil and shea butter to provide different qualities. For example, olive oil provides mildness in soap; coconut oil provides lots of lather; while coconut and palm oils provide hardness. Most common, is a combination of coconut, palm, and olive oils.

Process

Cold process soap making is done without heating the soap batter, while hot process soap making requires that the soap batter be heated. Both processes are described after the general soap making process description.

General Soap Making Process

Soap making requires using saponification charts[4] to determine the exact measurement of lye and fat to ensure that all of the ingredients will successfully react with each other and that no free lye will remain in the soap.[5] Excess unreacted lye in the soap will result in a very high pH and can burn or irritate skin. Not enough lye will result in greasy sludge that will not form solid bars of soap.

Some soap makers "superfat" their soap by adding 5-10% excess fats so that some oils will remain in the finished bars of soap. Likewise, other soap makers discount the formulated amount of lye to 90-95% and withhold some of the lye from the recipe to ensure that some free oils will remain in the finished bars of soap.[6]

The lye is dissolved in water. Then oils are heated and liquify if they are solid at room temperature. Once fats and lye water have both cooled the same temperature and are 80-100° F, they are combined. This mixture of lye water and fats is stirred until "trace" occurs and the mixture becomes a soap batter. There are varying levels of trace: A light trace implies a thinner soap batter and a heavy trace implies a thicker soap batter. Additives, such as essential oils, fragrance oils, botanicals, clays, colorants or other fragrance materials, are combined with the soap batter at different degrees of trace, depending upon the additive. With elapsed time and continued agitation the soap batter will continue to thicken. The cold process soap batter is then poured into molds, while hot process soap batter is poured into a double boiler or crockpot to be heated.

Cold Process

Although cold-process soapmaking takes place at room temperature; first, the fats are heated to ensure the liquification of the fats used. Then, when the lye water solution is added to the fats, it should be the same temperature of the melted oils and both are typically between 80-90° F. An external heat source is not necessary but the molded soap should be incubated by being wrapped in blankets or towels for 24 hours after being poured into the mold. Milk soaps are the exception. They do not require insulation. Insulation may cause the milk to sour. The soap will continue to exothermically give off heat for many hours after being molded. During this time, it is normal for the soap to go through a "gel phase" where the opaque soap will turn somewhat transparent for several hours before turning opaque again. The soap may be removed from the mold after 24 hours but the saponification process takes several weeks to be complete.

Hot Process

Unlike cold processed soap, all hot processed soap experiences a "gel phase" as a result of being heated, such as in a double boiler or crockpot. Hot process soap may used soon after being removed from the mold because lye and fat saponify more quickly at the higher temperatures used in hot process soap making.

Purification and Finishing

The common process of purifying soap involves removal of sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide, and glycerol. These components are removed by boiling the crude soap curds in water and re-precipitating the soap with salt.[citation needed]

Most of the water is then removed from the soap. This was traditionally done on a chill roll which produced the soap flakes commonly used in the 1940s and 1950s. This process was superseded by spray dryers and then by vacuum dryers.[citation needed]

The dry soap (approximately 6-12% moisture) is then compacted into small pellets. These pellets are now ready for soap finishing, the process of converting raw soap pellets into a salable product, usually bars.[citation needed]

Soap pellets are combined with fragrances and other materials and blended to homogeneity in an amalgamator (mixer). The mass is then discharged from the mixer into a refiner which, by means of an auger, forces the soap through a fine wire screen. From the refiner the soap passes over a roller mill (French milling or hard milling) in a manner similar to calendering paper or plastic or to making chocolate liquor. The soap is then passed through one or more additional refiners to further plasticize the soap mass. Immediately before extrusion it passes through a vacuum chamber to remove any entrapped air. It is then extruded into a long log or blank, cut to convenient lengths, passed through a metal detector and then stamped into shape in refrigerated tools. The pressed bars are packaged in many ways.[citation needed]

Sand or pumice may be added to produce a scouring soap. This process is most common in creating soaps used for human hygiene. The scouring agents serve to remove dead skin cells from the surface being cleaned. This process is called exfoliation. Many newer materials are used for exfoliating soaps which are effective but do not have the sharp edges and poor size distribution of pumice.[citation needed]

History

Early History

The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BC in Ancient Babylon.[7] A formula for soap consisting of water, alkali and cassia oil was written on a Babylonian clay tablet around 2200 BC. On this clay tablet a series of human sacrificial ceremonies took place hundreds of years before the bodies were burned and the ashes of the humans mixed with water to create Lye when the lye was later mixed with water end the melted fat of the bodies a thick soapy discharge crept from the clay slab of rock.

The Ebers papyrus (Egypt, 1550 BC) indicates that ancient Egyptians bathed regularly and combined animal and vegetable oils with alkaline salts to create a soap-like substance. Egyptian documents mention that a soap-like substance was used in the preparation of wool for weaving.

Roman History

It had been reported that a factory producing soap-like substances was found in the ruins of Pompeii (AD 79). However, this has proven to be a misinterpretation of the survival of some soapy mineral substance,[citation needed] probably soapstone at the Fullonica where it was used for dressing recently cleansed textiles. Unfortunately this error has been repeated widely and can be found in otherwise reputable texts on soap history. The ancient Romans were generally ignorant of soap's detergent properties, and made use of the strigil to scrape dirt and sweat from the body. The word "soap" (Latin sapo) appears first in a European language in Pliny the Elder's Historia Naturalis, which discusses the manufacture of soap from tallow and ashes, but the only use he mentions for it is as a pomade for hair; he mentions rather disapprovingly that among the Gauls and Germans men are likelier to use it than women.[8]

A story encountered in some places claims that soap takes its name from a supposed "Mount Sapo" where ancient Romans sacrificed animals. Rain would send a mix of animal tallow and wood ash down the mountain and into the clay soil on the banks of the Tiber. Eventually, women noticed that it was easier to clean clothes with this "soap". The location of Mount Sapo is unknown, as is the source of the "ancient Roman legend" to which this tale is typically credited.[1] In fact, the Latin word sapo simply means "soap"; it was borrowed from a Celtic or Germanic language, and is cognate with Latin sebum, "tallow", which appears in Pliny the Elder's account. Roman animal sacrifices usually burned only the bones and inedible entrails of the sacrificed animals; edible meat and fat from the sacrifices were taken by the humans rather than the gods. Animal sacrifices in the ancient world would not have included enough fat to make much soap. The legend about Mount Sapo is probably apocryphal.

Muslim History

True soaps made from vegetable oils (such as olive oil), aromatic oils (such as thyme oil) and lye (al-Soda al-Kawia) were first produced by Muslim chemists in the medieval Islamic world.[9] The formula for soap used since then hasn't changed. From the beginning of the 7th century, soap was produced in Nablus (West Bank, Palestine), Kufa (Iraq) and Basra (Iraq). Soaps, as we know them today, are descendants of historical Arabian Soaps. Arabian Soap was perfumed and colored, some of the soaps were liquid and others were solid. They also had special soap for shaving. It was sold for 3 Dirhams (0.3 Dinars) a piece in 981 AD. The Persian chemist Al-Razi wrote a manuscript on recipes for true soap. A recently discovered manuscript from the 13th century details more recipes for soap making; e.g. take some sesame oil, a sprinkle of potash, alkali and some lime, mix them all together and boil. When cooked, they are poured into molds and left to set, leaving hard soap.

In semi-modern times soap was made by mixing animal fats with lye. Because of the caustic lye, this was a dangerous procedure (perhaps more dangerous than any present-day home activities) which could result in serious chemical burns or even blindness. Before commercially-produced lye (sodium hydroxide) was commonplace, potash, potassium hydroxide, was produced at home for soap making from the ashes of a hardwood fire.

Modern History

Castile soap was later produced in Europe from the 16th century.

In modern times, the use of soap has become universal in industrialized nations due to a better understanding of the role of hygiene in reducing the population size of pathogenic microorganisms. Manufactured bar soaps first became available in the late nineteenth century, and advertising campaigns in Europe and the United States helped to increase popular awareness of the relationship between cleanliness and health.

Rarely, conditions allow for corpses to naturally turn in to a soap-like substance, such as the Soap Lady on exhibit in the Mutter Museum.

Commercial soap production

Until the Industrial Revolution, soap-making was done on a small scale and the product was rough. Andrew Pears started making a high-quality, transparent soap in 1789 in London. With his grandson, Francis Pears, they opened a factory in Isleworth in 1862. William Gossage produced low-price good quality soap from the 1850s. Robert Spear Hudson began manufacturing a soap powder in 1837, initially by grinding the soap with a mortar and pestle. William Hesketh Lever and his brother, James, bought a small soap works in Warrington in 1885 and founded what is still one of the largest soap businesses, now called Unilever. These soap businesses were among the first to employ large scale advertising campaigns.

See also

|

|

Notes

- ^ Failor, Catherine (2000).

- ^ http://www.pallasathenesoap.com/trivia.html Pallas Athene Soap

- ^ Certified Lye™

- ^ http://www.certified-lye.com/lye-soap.html#LyeSoap Certified Lye

- ^ http://www.natural-soap-directory.com/soap-terms.html#make-soap Natural Soap Directory

- ^ http://www.natural-soap-directory.com/soap-terms.html Natural Soap Directory

- ^ Willcox, Michael (2000). "Soap". In Hilda Butler (ed.). Poucher's Perfumes, Cosmetics and Soaps (10th edition ed.). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 453.

The earliest recorded evidence of the production of soap-like materials dates back to around 2800 BC in Ancient Babylon.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XXVIII.191.

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries.

References

- "Certified Lye - Using Lye to Make Soap" (HTML). Certified Lye™.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - Failor, Catherine (2000). Making Transparent Soap: The Art of Crafting, Molding, Scenting, and Coloring. North Adams, MA: Storey Books. p. 64. ISBN 158017244X.

- Garzena, Patrizia - Tadiello, Marina (2004). Soap Naturally - Ingredients, methods and recipes for natural handmade soap. Programmer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9756764-0-0.

External links

|