Stalker (1979 film): Difference between revisions

m rmv per WP:EL |

Homage |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

[[Chris Marker]], in his 1982 film [[Sans Soleil]], references Tarkovsky's Stalker through the use of the term "Zone" to describe the space in which images and their attached memories are transformed. |

[[Chris Marker]], in his 1982 film [[Sans Soleil]], references Tarkovsky's Stalker through the use of the term "Zone" to describe the space in which images and their attached memories are transformed. |

||

[[Robert Rich]] and Brian [[Lustmord]] recorded an album of [[dark ambient]] music inspired by the title and the hypnotic minimalism of Tarkovsky's Stalker. It was released in 1995 on [[Fathom Records]]. |

|||

[[Björk]]'s song "The Dull Flame of Desire" (released on her album Volta) takes the poem from the end of the movie as lyrics. In the booklet of the album she mentions the movie as source for the poem. |

|||

[[Richie Hawtin]]'s [[DE9: Transitions| DE9 | Transitions]] DVD includes a short video inspired by, and credited to, this movie. (Also mentioned in this [http://www.residentadvisor.net/review-view.aspx?id=3354 review].) |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 11:19, 13 May 2008

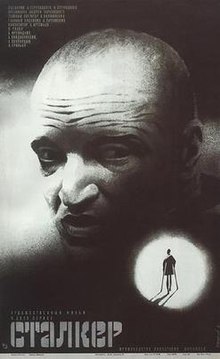

| Stalker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Written by | Arkadi Strugatsky Boris Strugatsky |

| Produced by | Aleksandra Demidova |

| Starring | Alexander Kaidanovsky Anatoli Solonitsyn Nikolai Grinko |

| Music by | Eduard Artemyev |

| Distributed by | Mosfilm |

Release date | August 1979 (Soviet Union) |

Running time | 163 min |

| Language | Russian |

Stalker (Russian: Сталкер) is a 1979 film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. It describes the journey of three men travelling through a post-apocalyptic wilderness called the Zone to find a room with the potential to fulfil one's innermost desires. The title role is played by Alexander Kaidanovsky, who guides two others through the area, the Writer, played by Anatoly Solonitsyn, and the Professor, played by Nikolai Grinko. Alisa Freindlich played the Stalker's wife.

The film is loosely based on the novel Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. An early draft of the screenplay was also published as a novel Stalker that differs much from the finished film. In Roadside Picnic, the Zone is full of strange artefacts and phenomena that defy known science. A vestige of this idea carries over to the film, in the form of Stalker's habit of throwing metal nuts down a path before walking along it. The characters in Roadside Picnic do something similar when they suspect they are near gravitational anomalies that could crush them.

"Stalker", an English word employed in the original novel, should not be understood in the contemporary, sinister sense, but rather in the older sense of a tracker of game.

Plot synopsis

The setting of the film is a tiny town on the outskirts of "The Zone", a wilderness area which has been cordoned off by the government. The film suggests that the Zone was the site of a meteor strike, or perhaps of a UFO landing. The film's main character, the Stalker, works as a guide to bring people in and out of the Zone, specifically to a room which is said to grant wishes.

The film begins with the Stalker in his home with his wife and daughter. His wife emotionally urges him not to leave her again, but he ignores her pleas. The Stalker goes to a bar, where he meets the Writer and the Professor, who will be his clients on his next trip into the Zone. Writer and Professor are not identified by name–the Stalker prefers to refer to them in this way. The three of them evade the military blockade that guards the Zone using a jeep -- attracting gunfire from the guards as they go -- and then ride into the heart of the Zone on a small trolley car.

Once in the Zone, the Stalker tells the others that they must do exactly as he says to survive the dangers that are all around them. The Stalker tests various routes by throwing metal nuts tied with strips of cloth ahead of him before walking into a new area. The Zone usually appears peaceful and harmless, with no visible dangers anywhere–Writer is skeptical that there is any real danger, while Professor generally follows the Stalker's advice.

Much of the film focuses on the trip through the dangerous Zone, and the philosophical discussions which the characters share about their reasons for wanting to visit the room. Writer appears concerned that he is losing his inspiration, Professor apparently hopes to win a Nobel prize, the Stalker -- who explains that he never visits the room himself -- quotes from the New Testament and bemoans the loss of faith in society. They first walk through meadows, and then into a tunnel which the Stalker calls "the meat grinder". Although the Stalker describes extreme danger at all times, no harm comes to any of the three men. Their journey ends when they arrive at the entrance of the room. Throughout the film, the Stalker refers to a previous Stalker, named "Porcupine," who led his poet brother to death in the Zone, won the lottery, and then hanged himself. When the Writer confronts the Stalker about his knowledge of the Zone and the Room, he says that it all comes from Porcupine.

At this point the Professor reveals, partly in a phone call to one of his colleagues, some of his true motives for having come to the room. He has brought a bomb with him, and intends to destroy the room out of fear that it could be used for personal gain by evil men. The three men fight verbally and physically, and eventually the Professor decides not to use his bomb. A classic Tarkovskian long take, with the camera in the room, leaves the men sitting outside the room, and does not clarify whether they ever enter. The take is long enough to show a rainstorm that spontaneously occurs, from beginning to end.

The next scene shows the Stalker, Writer, and Professor back in the bar. The Writer and Professor leave, and the Stalker's wife and child arrive. As the Stalker leaves the bar with his family, we see that his child, nick-named "Monkey" (who earlier dialogue has suggested is affected by some form of genetic mutation as a "child of the zone") is crippled, and cannot walk unaided. The film ends with a long shot of Monkey alone in the kitchen. She recites a poem, and then lays her head on the table and appears to telekinetically push three drinking glasses across the table, with one falling to the floor. As the third glass begins to move, a train passes by (as in the beginning of the film), causing the entire apartment to shake, leaving the audience to wonder whether it was Monkey or the vibrations from the train that moved the glasses.[1]

Style and themes

Like Tarkovsky's other films, Stalker relies on long takes with slow, subtle movement of camera, rejecting the conventional use of rapid montage to explain the narrative and achieve artificial dramatic peaks. Instead, Tarkovsky's prolonged shots capture a poetic reality that is naturalistic and yet far removed from ordinary perception. As he did with Solaris, Tarkovsky took great liberties in adapting the screenplay to emphasize the philosophical and metaphysical angles that concerned him the most.

While the film retains some of the science fiction trappings of the novel, it is most concerned with themes of personal faith that are important to Tarkovsky, there are many themes that allude to Existentialism particularly Kierkegaard and Dostoyevsky who was referred to in the earlier film Solaris. We see throughout the film social standing being derided and eroded with the high standing characters of “Professor” and “Writer” being allegory for social standing and its mediocre worth once the trappings of society are removed. Throughout the film the viewer is also drawn into a world that fundamentally questions whether our innermost desires are of any worth which ties in with Christian theism which can be seen in many of Tarkovsky’s films, and furthermore the fear and requirement of faith is similar to the concept of Dread in Kierkegaard, the use of faith throughout the zone further alludes to a fundamentally Christian story this is combined with motifs such as the sequence where we see guns and other worldly affects rusting away in the Zone.

It has been pointed out by many film experts and psychologists (such as Slavoj Zizek) that the Zone is not solely within the room, and that although many of the characters see dreams fulfilled in the Zone such as the professors belittling of a colleague, they still display dissatisfaction, at this point we see three characters against one another. The zone cannot fulfil them or their desires, perhaps because the characters are too bound by their own structures and patterns of behaviour making the Zone only able to fulfil baser needs. The film alludes to this with Stalker narrating a sequence claiming to desire that all three men become like ‘Children’ and be fulfilled by the Zone.[citation needed]

Production

The central part of the film was shot in a few days at a deserted hydro power plant on the Jägala river near Tallinn, Estonia. (The shot before they enter the zone is an old Flora chemical factory in the center of Tallinn (next to the old Rotermann salt store), some shots from the zone are filmed in Maardu, next to the Iru powerplant and the shot with the gates to the Zone is filmed in Lasnamäe, next to Punane street behind the Idakeskus.) When the team got back to Moscow, they found that all of the film had been improperly developed. The film was shot on experimental Kodak stock with which Soviet laboratories were unfamiliar. There was also speculation that the Soviet authorities deliberately mishandled the stock of the film. Tarkovsky was officially frowned upon by the Soviet authorities, not because of his political stances (Tarkovsky rarely talked about politics), but because his films dealt with issues of spirituality and the quest for God. The USSR was an officially atheistic state, and Tarkovsky's films digressed from this official line, making him suspect. However, his films were relatively popular in the USSR, and he was allowed to continue making films.

During the shooting before the film stock problem was discovered, relations with the first cinematographer, Georgy Rerberg, were in serious deterioration. After screening the material, Rerberg left the first screening session and never came back. By the time this film stock defect was found out, Tarkovsky had shot all the outdoor scenes. Set designer Rashit Safiullin was interviewed for the 2000 Rusico DVD, and he contends that Tarkovsky was so despondent that he wanted to abandon further production of the film.

After the loss of the film stock the Soviet film boards wanted to shut the film down, officially writing it off. But Tarkovsky came up with a solution - he asked to make a two part film, which meant additional deadlines and more funds. Tarkovsky ended up re-shooting almost all of the film with a new cinematographer, Aleksandr Knyazhinsky. Tarkovsky made the film more of a philosophical metaphor than a straightforward science fiction film (similar to what he did in Solaris). He was constantly rewriting the script during the actual shooting and during the dubbing and editing (the film was post-dubbed, like many Soviet films were).

Many people involved in the film production had untimely deaths. Many attribute the long and arduous shooting schedule of the film, and the physical conditions of the terrain where it was made. Vladimir Sharun recalls:

We were shooting near Tallinn in the area around the small river Pirita with a half-functioning hydroelectric station. Up the river was a chemical plant and it poured out poisonous liquids downstream. There is even this shot in Stalker: snow falling in the summer and white foam floating down the river. In fact it was some horrible poison. Many women in our crew got allergic reactions on their faces. Tarkovsky died from cancer of the right bronchial tube. And Tolya Solonitsyn too. That it was all connected to the location shooting for Stalker became clear to me when Larissa Tarkovskaya died from the same illness in Paris.

It is suspected that the 1957 accident in the Mayak nuclear fuel reprocessing plant, which resulted in a several thousand square kilometer deserted "zone" outside the reactor [2], may have influenced this film. Seven years after the making of the film, the Chernobyl accident completed the circle. In fact, those employed to take care of the abandoned nuclear power plant refer to themselves as "stalkers", and to the area around the damaged reactor as the "Zone." [3]

Crew

- Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

- Second director: Tarkovsky's wife Larissa Tarkovskaya

- Screenplay: Boris Strugatsky, Arkady Strugatsky & Andrei Tarkovsky (uncredited)

- Editor: Lyudmila Feiginova

- Music: Eduard Artemyev

- First camera: Georgi Rerberg (none of his footage was used, see above)

- Second camera: Aleksandr Knyazhinsky (the footage used in the movie)

- Sound designer: Vladimir Ivanovich Sharun

- Set designer: Rashit Safiullin

Cast

- Stalker - Alexander Kaidanovsky

- Stalker's Wife - Alisa Freindlich

- Writer - Anatoly Solonitsyn

- Professor - Nikolai Grinko

Making of (Gallery)

-

Andrei Tarkovsky (director), Anatoli Solonitsyn (actor), Nikolai Grinko (actor) and Alexander Kaidanovsky (actor).

-

Alexander Kaidanovsky (actor) and Andrei Tarkovsky (director).

-

Andrei Tarkovsky (director), Alexander Kaidanovsky (actor), Anatoli Solonitsyn (actor) and Nikolai Grinko (actor).

Homage

Chris Marker, in his 1982 film Sans Soleil, references Tarkovsky's Stalker through the use of the term "Zone" to describe the space in which images and their attached memories are transformed.

Robert Rich and Brian Lustmord recorded an album of dark ambient music inspired by the title and the hypnotic minimalism of Tarkovsky's Stalker. It was released in 1995 on Fathom Records.

Björk's song "The Dull Flame of Desire" (released on her album Volta) takes the poem from the end of the movie as lyrics. In the booklet of the album she mentions the movie as source for the poem.

Richie Hawtin's DE9 | Transitions DVD includes a short video inspired by, and credited to, this movie. (Also mentioned in this review.)

See also

- S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, a 2007 video game based on elements of Stalker and Roadside Picnic.

References

- ^ Nostalghia.com article

- ^ Trivia section of the film's IMDB entry

- ^ Johncoulhart.com article

External links

- Stalker at IMDb

- Stalker section at Nostalghia.com

- International promotion posters

- Template:Ru icon Stills from Stalker, (Russian text)

- Stalker at the Arts & Faith Top100 Spiritually Significant Films list

- Template:Et iconGeopeitus.ee - Information concerning Stalker Location Filming

- Template:Ru icon Discussion of making the film, part 1. ("Искусство кино," in Russian, Georgii Rerberg, Marianna Chugunova, Evgenii Tsymbal)

- Template:Ru icon Discussion of making the film, part 2. ("Искусство кино," in Russian, Georgii Rerberg, Marianna Chugunova, Evgenii Tsymbal)

- Not enough ("Только этого мало"), a poem of Arseny Tarkovsky