Space elevator: Difference between revisions

Fixing reference errors and rescuing orphaned refs ("pearson" from rev 242230270) |

Wolfkeeper (talk | contribs) →Powering climbers: read citation? |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 222: | Line 222: | ||

[[Image:SpaceElevatorInClouds.jpg|thumb|right|Most space elevator designs call for a '''climber''' to move autonomously along a stationary cable.]] |

[[Image:SpaceElevatorInClouds.jpg|thumb|right|Most space elevator designs call for a '''climber''' to move autonomously along a stationary cable.]] |

||

A space elevator cannot be an elevator in the typical sense (with moving cables) due to the need for the cable to be significantly wider at the center than the tips. While various designs employing moving cables have been proposed |

A space elevator cannot be an elevator in the typical sense (with moving cables) due to the need for the cable to be significantly wider at the center than the tips. While various designs employing moving cables have been proposed, most cable designs call for the "elevator" to climb up a stationary cable. |

||

Climbers cover a wide range of designs. On elevator designs whose cables are planar ribbons, most propose to use pairs of rollers to hold the cable with friction. |

Climbers cover a wide range of designs. On elevator designs whose cables are planar ribbons, most propose to use pairs of rollers to hold the cable with friction. Usually, elevators are designed for climbers to move only upwards, because that is where most of the payload goes. For returning payloads, atmospheric reentry on a heat shield is a very competitive option{{Fact|date=September 2008}}, which also avoids the problem of docking to the elevator in space. |

||

Climbers must |

Climbers must be paced at optimal timings so as to minimize cable stress and oscillations and to maximize throughput. Lighter climbers can be sent up more often, with several going up at the same time. This increases throughput somewhat, but lowers the mass of each individual payload. |

||

[[Image:Space elevator balance of forces.png|thumb|250px|As the car climbs, the elevator takes on a 1 degree lean, due to the top of the elevator traveling faster than the bottom around the Earth (Coriolis effect). This diagram is not to scale.]] |

[[Image:Space elevator balance of forces.png|thumb|250px|As the car climbs, the elevator takes on a 1 degree lean, due to the top of the elevator traveling faster than the bottom around the Earth (Coriolis effect). This diagram is not to scale.]] |

||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

Both power and energy are significant issues for climbers- the climbers need to gain a large amount of potential energy as quickly as possible to clear the cable for the next payload. |

Both power and energy are significant issues for climbers- the climbers need to gain a large amount of potential energy as quickly as possible to clear the cable for the next payload. |

||

Nuclear energy and solar power have been proposed |

Nuclear energy and solar power have been proposed, but generating enough energy to reach the top of the elevator in any reasonable time without weighing too much is not feasible.<ref>[http://www.isr.us/Downloads/niac_pdf/chapter4.html NIAC Space Elevator Report chapter4]</ref>{{Citation broken|date=September 2008}} |

||

The |

The proposed method is laser power beaming, using megawatt powered free electron or solid state lasers in combination with adaptive mirrors approximately 10 m wide and a photovoltaic array on the climber tuned to the laser frequency for efficiency.<ref name="niac"/> A major obstacle for any climber design is the dissipation of the substantial amount of waste heat generated due to the less than perfect efficiency of any of the power methods. |

||

Magnetic levitation achieved through superconduction could{{Fact|date=September 2008}} be used as a possible means of propelling platforms upwards on the space elevator. |

|||

[[Nihon University]] professor engineering [[Yoshio Aoki]], the director of the [[Japan Space Elevator Association]], suggested including a second cable and using the superconductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.<ref name=JapanUKTimes/> |

[[Nihon University]] professor engineering [[Yoshio Aoki]], the director of the [[Japan Space Elevator Association]], suggested including a second cable and using the superconductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.<ref name=JapanUKTimes/> |

||

| Line 263: | Line 262: | ||

Because of this, Martian [[areostationary orbit]] is much closer to the surface, and hence the elevator would be much shorter. Exotic materials might not be required to construct such an elevator. However, building a Martian elevator would be a unique challenge because the Martian moon [[Phobos (moon)|Phobos]] is in a low orbit,{{Fact|date=August 2008}} and intersects the equator regularly (twice every orbital period of 11 h 6 min). |

Because of this, Martian [[areostationary orbit]] is much closer to the surface, and hence the elevator would be much shorter. Exotic materials might not be required to construct such an elevator. However, building a Martian elevator would be a unique challenge because the Martian moon [[Phobos (moon)|Phobos]] is in a low orbit,{{Fact|date=August 2008}} and intersects the equator regularly (twice every orbital period of 11 h 6 min). |

||

A [[lunar space elevator]] can possibly be built with currently |

A [[lunar space elevator]] can possibly be built with currently available technology about 50,000 kilometers long extending though the Earth-moon L1 point from an anchor point near the center of the visible part of Earth's moon.<ref name="Pearson 2005"/> |

||

On the far side of the moon, a [[lunar space elevator]] would need to be very long (more than twice the length of an Earth elevator) but due to the low gravity of the Moon, can be made of existing engineering materials.<ref name="Pearson 2005">{{cite web| url=http://www.niac.usra.edu/files/studies/final_report/1032Pearson.pdf| last=Pearson| year= 2005| title=Lunar Space Elevators for Cislunar Space Development Phase I Final Technical Report| first=Jerome| coauthors= Eugene Levin, John Oldson and Harry Wykes| format=PDF}}</ref> |

On the far side of the moon, a [[lunar space elevator]] would need to be very long (more than twice the length of an Earth elevator) but due to the low gravity of the Moon, can be made of existing engineering materials.<ref name="Pearson 2005">{{cite web| url=http://www.niac.usra.edu/files/studies/final_report/1032Pearson.pdf| last=Pearson| year= 2005| title=Lunar Space Elevators for Cislunar Space Development Phase I Final Technical Report| first=Jerome| coauthors= Eugene Levin, John Oldson and Harry Wykes| format=PDF}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 16:33, 1 October 2008

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

A space elevator is a proposed structure designed to transport material from a celestial body's surface into space. Many variants have been proposed and all involve travelling along a fixed structure instead of using rocket powered spacelaunch. The concept most often refers to a structure that reaches from the surface of the Earth to geostationary orbit (GSO) and a counter-mass beyond.

The concept of a space elevator dates back to 1895, when Konstantin Tsiolkovsky,[1] proposed a compression structure, (that is, a free-standing tower), or "Tsiolkovsky tower" reaching from the surface of Earth to geostationary orbit. Most recent discussions focus on tensile structures (tethers) reaching from geostationary orbit to the ground. (A tensile structure would be held in tension between Earth and the counterweight in space, somewhat like a suspension bridge spanning a river.) Space elevators have also sometimes been referred to as beanstalks, space bridges, space lifts, space ladders, skyhooks, orbital towers, or orbital elevators.

Current (2008) technology is not capable of manufacturing practical engineering materials that are sufficiently strong and light to build an Earth based space elevator as the total mass of conventional materials needed to construct such a structure would be far too great. Recent conceptualizations for a space elevator are notable in their plans to use carbon nanotube-based materials as the tensile element in the tether design, since the measured strength of microscopic carbon nanotubes appears great enough to make this theoretically possible. Current materials can produce elevators for other locations in the solar system, such as Mars, that have weaker gravity than Earth.[2]

The Japanese have announced interest in being the first to develop a Space Elevator with a potential US$10 Billion project to produce the necessary carbon nanofiber and then a Space Elevator.

Geostationary orbital tethers

This concept, also called an orbital space elevator, geostationary orbital tether, or a beanstalk, is a subset of the skyhook concept, and is what people normally think of when the phrase 'Space elevator' is used (although there are variants).

Construction would be a vast project: a tether would have to be built of a material that could endure tremendous stress while also being light-weight, cost-effective, and manufacturable in great quantities. Today's materials technology does not meet these requirements, although carbon nanotube technology shows great promise. A considerable number of other novel engineering problems would also have to be solved to make a space elevator practical. Not all problems regarding feasibility have yet been addressed. Nevertheless, the LiftPort Group stated in 2002[3] that by developing the technology, the first space elevator could be operational by 2014.[4][5]

History

Early concepts

The key concept of the space elevator appeared in 1895 when Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was inspired by the Eiffel Tower in Paris to consider a tower that reached all the way into space, built from the ground up to an altitude of 35,790 kilometers above sea level (geostationary orbit).[6] He noted that a "celestial castle" at the top of such a spindle-shaped cable would have the "castle" orbiting Earth in a geo stationary orbit (i.e. the castle would remain over the same spot on Earth's surface).

Tsiolkovsky's tower would be able to launch objects into orbit without a rocket. Since the elevator would attain orbital velocity as it rode up the cable, an object released at the tower's top would also have the orbital velocity necessary to remain in geostationary orbit. Unlike more recent concepts for space elevators, Tsiolkovsky's (conceptual) tower was a compression structure, rather than a tension (or "tether") structure.

Twentieth century

Building a compression structure from the ground up proved an unrealistic task as there was no material in existence with enough compressive strength to support its own weight under such conditions.[7] In 1959 another Russian scientist, Yuri N. Artsutanov, suggested a more feasible proposal. Artsutanov suggested using a geostationary satellite as the base from which to deploy the structure downward. By using a counterweight, a cable would be lowered from geostationary orbit to the surface of Earth, while the counterweight was extended from the satellite away from Earth, keeping the center of gravity of the cable motionless relative to Earth. Artsutanov's idea was introduced to the Russian-speaking public in an interview published in the Sunday supplement of Komsomolskaya Pravda (usually translated as "Young Person's Pravda" in English) in 1960,[8] but was not available in English until much later. He also proposed tapering the cable thickness so that the tension in the cable was constant—this gives a thin cable at ground level, thickening up towards GSO.

Making a cable over 35,000 kilometers long is a difficult task. In 1966, Isaacs, Vine, Bradner and Bachus, four American engineers, reinvented the concept, naming it a "Sky-Hook," and published their analysis in the journal Science.[9] They decided to determine what type of material would be required to build a space elevator, assuming it would be a straight cable with no variations in its cross section, and found that the strength required would be twice that of any existing material including graphite, quartz, and diamond.

In 1975 an American scientist, Jerome Pearson, reinvented the concept yet again, publishing his analysis in the journal Acta Astronautica. He designed[10] a tapered cross section that would be better suited to building the elevator. The completed cable would be thickest at the geostationary orbit, where the tension was greatest, and would be narrowest at the tips to reduce the amount of weight per unit area of cross section that any point on the cable would have to bear. He suggested using a counterweight that would be slowly extended out to 144,000 kilometers (almost half the distance to the Moon) as the lower section of the elevator was built. Without a large counterweight, the upper portion of the cable would have to be longer than the lower due to the way gravitational and centrifugal forces change with distance from Earth. His analysis included disturbances such as the gravitation of the Moon, wind and moving payloads up and down the cable. The weight of the material needed to build the elevator would have required thousands of Space Shuttle trips, although part of the material could be transported up the elevator when a minimum strength strand reached the ground or be manufactured in space from asteroidal or lunar ore.

In 1977, Hans Moravec published an article called "A Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhook", in which he proposed an alternative space elevator concept, using a rotating cable,[11] in which the rotation speed exactly matches the orbital speed in such a way that the instantaneous velocity at the point where the cable was at the closest point to the Earth was zero. This concept is an early version of a space tether transportation system.

In 1979, space elevators were introduced to a broader audience with the simultaneous publication of Arthur C. Clarke's novel, The Fountains of Paradise, in which engineers construct a space elevator on top of a mountain peak in the fictional island country of Taprobane (loosely based on Sri Lanka, albeit moved south to the equator), and Charles Sheffield's first novel, The Web Between the Worlds, also featuring the building of a space elevator. Three years later, in Robert A. Heinlein's 1982 novel Friday the principal character makes use of the "Nairobi Beanstalk" in the course of her travels.

21st century

After the development of carbon nanotubes in the 1990s, engineer David Smitherman of NASA/Marshall's Advanced Projects Office realized that the high strength of these materials might make the concept of an orbital skyhook feasible, and put together a workshop at the Marshall Space Flight Center, inviting many scientists and engineers to discuss concepts and compile plans for an elevator to turning the concept into a reality.[12] The publication he edited compiling information from the workshop, "Space Elevators: An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium",[13] provides an introduction to the state of the technology at the time, and summarizes the findings.

Another American scientist, Bradley C. Edwards, suggested creating a 100,000 km long paper-thin ribbon using a carbon nanotube composite material. He chose a ribbon type structure rather than a cable because that structure might stand a greater chance of surviving impacts by meteoroids. Supported by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts, the work of Edwards was expanded to cover the deployment scenario, climber design, power delivery system, orbital debris avoidance, anchor system, surviving atomic oxygen, avoiding lightning and hurricanes by locating the anchor in the western equatorial Pacific, construction costs, construction schedule, and environmental hazards.[14][15] The largest holdup to Edwards' proposed design is the technological limits of the tether material. His calculations call for a fiber composed of epoxy-bonded carbon nanotubes with a minimal tensile strength of 130 GPa (including a safety factor of 2); however, tests in 2000 of individual single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), which should be notably stronger than an epoxy-bonded rope, indicated the strongest measured as 52 GPa.[16] Multi-walled carbon nanotubes have been measured with tensile strengths up to 63 GPa.[17]

In order to speed development of space elevators, proponents are planning several competitions, similar to the Ansari X Prize, for relevant technologies.[18][19] Among them are Elevator:2010 which will organize annual competitions for climbers, ribbons and power-beaming systems, the Robolympics Space Elevator Ribbon Climbing competition,[20] as well as NASA's Centennial Challenges program which, in March 2005, announced a partnership with the Spaceward Foundation (the operator of Elevator:2010), raising the total value of prizes to US$400,000.[21][22]

In 2005, "the LiftPort Group of space elevator companies announced that it will be building a carbon nanotube manufacturing plant in Millville, New Jersey, to supply various glass, plastic and metal companies with these strong materials. Although LiftPort hopes to eventually use carbon nanotubes in the construction of a 100,000 km (62,000 mile) space elevator, this move will allow it to make money in the short term and conduct research and development into new production methods.The space elevator is proposed to launch in 2010."[needs update][23] On February 13, 2006 the LiftPort Group announced that, earlier the same month, they had tested a mile of "space-elevator tether" made of carbon-fiber composite strings and fiberglass tape measuring 5 cm wide and 1 mm (approx. 6 sheets of paper) thick, lifted with balloons.[24]

On August 24, 2006 the Japanese National Museum of Emerging Science and Technology in Tokyo started showing the animation movie 'Space Elevator', based on the ATA Space Elevator Project, also directed and edited by the project leader, Dr. Serkan Anilir. This movie shows a possible image of the cities of the future, placing the space elevator tower in the context of a new infrastructure in city planning, and aims to contribute to children's education. Currently2024, the movie is shown in all science museums in Japan.[25]

The x-Tech Projects company has also been founded to pursue the prospect of a commercial Space Elevator.[citation needed]

In 2007, Elevator:2010 held the 2007 Space Elevator games which featured US$500,000 awards for each of the two competitions, (US$1,000,000 total) as well as an additional US$4,000,000 to be awarded over the next five years for space elevator related technologies.[26] No teams won the competition, but a team from MIT entered the first 2-gram, 100% carbon nanotube entry into the competition.[27] Japan is hosting an international conference in November 2008 to draw up a timetable for building the elevator. [28]

In 2008 the book "Leaving the Planet by Space Elevator", by Dr. Brad Edwards and Philip Ragan, was published in Japanese and entered the Japanese best seller list.[29] This has led to a Japanese announcement of intent to build a Space Elevator at a projected price tag of £5 billion. In a report by Leo Lewis, Tokyo correspondent of The Times newspaper in England, plans by Shuichi Ono, chairman of the Japan Space Elevator Association, are unveiled. Lewis says: "Japan is increasingly confident that its sprawling academic and industrial base can solve those [construction] issues, and has even put the astonishingly low price tag of a trillion yen (£5 billion) on building the elevator. Japan is renowned as a global leader in the precision engineering and high-quality material production without which the idea could never be possible."[28]

Structure

The centrifugal force of earth's rotation is the main principle behind the elevator. As the earth rotates the centrifugal force tends to align the nanotube in a stretched manner. There are a variety of tether designs. Almost every design includes a base station, a cable, climbers, and a counterweight.

Base station

The base station designs typically fall into two categories—mobile and stationary. Mobile stations are typically large oceangoing vessels,[30] though airborne stations have been proposed[by whom?] as well.[citation needed] Stationary platforms would generally be located in high-altitude locations, such as on top of mountains, or even potentially on high towers.[7]

Mobile platforms have the advantage of being able to maneuver to avoid high winds, storms, and space debris. While stationary platforms don't have these advantages, they typically would have access to cheaper and more reliable power sources, and require a shorter cable. While the decrease in cable length may seem minimal (typically no more than a few kilometers)[citation needed], that can significantly reduce the minimal width of the cable at the center.

Cable

The cable must be made of a material with a large tensile strength/density ratio. A space elevator can be made relatively economically feasible if a cable with a density similar to graphite and a tensile strength of ~65–120 GPa can be mass-produced at a reasonable price.

Carbon nanotubes' theoretical tensile strength has been estimated between 140 and 177 GPa (depending on plane shape),[31] and its observed tensile strength has been variously measured from 63 to 150 GPa, close to the requirements for space elevator structures.[31][32] Nihon University professor engineering Yoshio Aoki, the director of the Japan Space Elevator Association, has stated that the cable would need to be four times stronger than what is currently2024 the strongest carbon nanotube fiber, or about 180 times stronger than steel.[28] Even the strongest fiber made of nanotubes is likely to have notably less strength than its components.

Improving tensile strength depends on further research on purity and different types of nanotubes.

By comparison, most steel has a tensile strength of under 2 GPa, and the strongest steel resists no more than 5.5 GPa.[33] The much lighter material Kevlar has a tensile strength of 2.6–4.1 GPa, while quartz fiber[34] and carbon nanotubes[31] can reach upwards of 20 GPa; the tensile strength of diamond filaments would theoretically be minimally higher.

Designs call for single-walled carbon nanotubes. While multi-walled nanotubes are easier to produce and have similar tensile strengths, there is a concern[citation needed] that the interior tubes would not be sufficiently coupled to the outer tubes to help hold the tension. However, if the nanotubes are long enough, even weak Van der Waals forces will be sufficient[citation needed] to keep them from slipping, and the full strength of individual nanotubes (single or multiwalled) could be realized macroscopically by spinning them into a yarn. It has also been proposed[by whom?] to chemically interlink the nanotubes in some way[vague], but it is likely that this would greatly compromise their strength. One such proposal is to take advantage of the high pressure interlinking properties of carbon nanotubes of a single variety.[35] While this would cause the tubes to lose some tensile strength by the trading of sp² bond (graphite, nanotubes) for sp³ (diamond), it will enable them to be held together in a single fiber by more than the usual, weak Van der Waals force (VdW), and allow manufacturing of a fiber of any length.

The technology to spin regular VdW-bonded yarn from carbon nanotubes is just in its infancy: the first success in spinning a long yarn, as opposed to pieces of only a few centimeters, was reported in March 2004[citation needed]; but the strength/weight ratio was not as good as Kevlar due to the inconsistent quality and short length of the tubes being held together by VdW.

As of 2006, carbon nanotubes cost $25/gram, and even a minimal, very low payload space elevator "seed ribbon" could have a mass of at least 18,000 kg. However, this price is declining, and large-scale production could result in strong economies of scale.[36]

Carbon nanotube fiber is an area of energetic worldwide research because the applications go much further than space elevators. Other suggested[by whom?] application areas include suspension bridges, new composite materials, lighter aircraft and rockets, armor technologies, and computer processor interconnects.[citation needed] This is good news for space elevator proponents because it is likely[citation needed] to push down the price of the cable material further.

Due to its enormous length a space elevator cable must be carefully designed to carry its own weight as well as the smaller weight of climbers. The required strength of the cable will vary along its length, since at various points it has to carry the weight of the cable below, or provide a centripetal force to retain the cable and counterweight above. In a 1998 report,[37] NASA researchers noted that "maximum stress [on a space elevator cable] is at geosynchronous altitude so the cable must be thickest there and taper exponentially as it approaches Earth. Any potential material may be characterized by the taper factor -- the ratio between the cable's radius at geosynchronous altitude and at the Earth's surface."

Climbers

A space elevator cannot be an elevator in the typical sense (with moving cables) due to the need for the cable to be significantly wider at the center than the tips. While various designs employing moving cables have been proposed, most cable designs call for the "elevator" to climb up a stationary cable.

Climbers cover a wide range of designs. On elevator designs whose cables are planar ribbons, most propose to use pairs of rollers to hold the cable with friction. Usually, elevators are designed for climbers to move only upwards, because that is where most of the payload goes. For returning payloads, atmospheric reentry on a heat shield is a very competitive option[citation needed], which also avoids the problem of docking to the elevator in space.

Climbers must be paced at optimal timings so as to minimize cable stress and oscillations and to maximize throughput. Lighter climbers can be sent up more often, with several going up at the same time. This increases throughput somewhat, but lowers the mass of each individual payload.

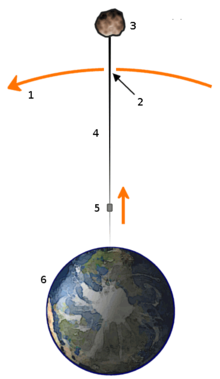

The horizontal speed of each part of the cable increases with altitude, proportional to distance from the center of the Earth, reaching orbital velocity at geostationary orbit. Therefore as a payload is lifted up a space elevator, it needs to gain not only altitude but angular momentum (horizontal speed) as well. This angular momentum is taken from the Earth's own rotation. As the climber ascends it is initially moving slightly more slowly than the cable that it moves onto (Coriolis effect) and thus the climber "drags" on the cable.

The overall effect of the centrifugal force acting on the cable causes it to constantly try to return to the energetically favourable vertical orientation, so after an object has been lifted on the cable the counterweight will swing back towards the vertical like an inverted pendulum. Provided that the Space Elevator is designed so that the center of weight always stays above geostationary orbit[38] for the maximum climb speed of the climbers, the elevator cannot fall over. Lift and descent operations must be carefully planned so as to keep the pendulum-like motion of the counterweight around the tether point under control.

By the time the payload has reached GEO the angular momentum (horizontal speed) is enough that the payload is in orbit.

The opposite process would occur for payloads descending the elevator, tilting the cable eastwards and insignificantly increasing Earth's rotation speed.

Powering climbers

Both power and energy are significant issues for climbers- the climbers need to gain a large amount of potential energy as quickly as possible to clear the cable for the next payload.

Nuclear energy and solar power have been proposed, but generating enough energy to reach the top of the elevator in any reasonable time without weighing too much is not feasible.[39][full citation needed]

The proposed method is laser power beaming, using megawatt powered free electron or solid state lasers in combination with adaptive mirrors approximately 10 m wide and a photovoltaic array on the climber tuned to the laser frequency for efficiency.[30] A major obstacle for any climber design is the dissipation of the substantial amount of waste heat generated due to the less than perfect efficiency of any of the power methods.

Nihon University professor engineering Yoshio Aoki, the director of the Japan Space Elevator Association, suggested including a second cable and using the superconductivity of carbon nanotubes to provide power.[28]

Counterweight

There have been several methods proposed for dealing with the counterweight need: a heavy object, such as a captured asteroid[6] or a space station, positioned past geostationary orbit, or extending the cable itself well past geostationary orbit. The latter idea has gained more support in recent years2024 due to the relative simplicity of the task and the fact that a payload that went to the end of the counterweight-cable would acquire considerable velocity relative to the Earth, allowing it to be launched into interplanetary space.

Additionally, Brad Edwards has proposed that initially elevators would be up-only, and that the elevator cars that are used to thicken up the cable could simply be parked at the top of the cable and act as a counterweight.

Launching into outer space

The velocities that might be attained at the end of Pearson's 144,000 km cable can be determined. The tangential velocity is 10.93 kilometers per second which is more than enough to escape Earth's gravitational field and send probes as far out as Saturn. If an object were allowed to slide freely along the upper part of the tower, a velocity high enough to escape the solar system entirely would be attained. This is accomplished by trading off overall angular momentum of the tower for velocity of the launched object, in much the same way one snaps a towel or throws a lacrosse ball. After such an operation a cable would be left with less angular momentum than required to keep its geostationary position. The rotation of the Earth would then pull on the cable increasing its angular velocity, leaving the cable swinging backwards and forwards about its starting point.

For higher velocities, the cargo can be electromagnetically accelerated, or the cable could be extended, although that would require additional strength in the cable.

Extraterrestrial elevators

A space elevator could also be constructed on other planets, asteroids and moons.

A Martian tether could be much shorter than one on Earth. Mars' surface gravity is 38% of Earth's, while it rotates around its axis in about the same time as Earth.[40] Because of this, Martian areostationary orbit is much closer to the surface, and hence the elevator would be much shorter. Exotic materials might not be required to construct such an elevator. However, building a Martian elevator would be a unique challenge because the Martian moon Phobos is in a low orbit,[citation needed] and intersects the equator regularly (twice every orbital period of 11 h 6 min).

A lunar space elevator can possibly be built with currently available technology about 50,000 kilometers long extending though the Earth-moon L1 point from an anchor point near the center of the visible part of Earth's moon.[41]

On the far side of the moon, a lunar space elevator would need to be very long (more than twice the length of an Earth elevator) but due to the low gravity of the Moon, can be made of existing engineering materials.[41]

Rapidly spinning asteroids or moons could use cables to eject materials in order to move the materials to convenient points, such as Earth orbits;[citation needed] or conversely, to eject materials in order to send the bulk of the mass of the asteroid or moon to Earth orbit or a Lagrangian point. This was suggested by Russell Johnston in the 1980s.[citation needed] Freeman Dyson, a physicist and mathematician, has suggested[citation needed] using such smaller systems as power generators at points distant from the Sun where solar power is uneconomical. For the purpose of mass ejection, it is not necessary to rely on the asteroid or moon to be rapidly spinning. Instead of attaching the tether to the equator of a rotating body, it can be attached to a rotating hub on the surface. This was suggested in 1980 as a "Rotary Rocket" by Pearson[42] and described very succinctly on the Island One website as a "Tapered Sling"[43]

Construction

The construction of a space elevator would be a vast project, requiring advances in engineering, manufacture and physical technology. One early plan involved lifting the entire mass of the elevator into geostationary orbit, and simultaneously lowering one cable downwards towards the Earth's surface while another cable is deployed upwards directly away from the Earth's surface.

Alternatively, if nanotubes with sufficient strength could be made in bulk, a single hair-like 18-metric ton (20 short ton) 'seed' cable be deployed in the traditional way then progressively heavier cables would be pulled up from the ground along it, repeatedly strengthening it until the elevator reaches the required mass and strength. This is much the same technique used to build suspension bridges.

Safety issues and construction difficulties

As with any structure, there are a number of ways in which things could go wrong. A space elevator would present a considerable navigational hazard, both to aircraft and spacecraft. Aircraft could be dealt with by means of simple air-traffic control restrictions, but impacts by space objects (in particular, by meteoroids and micrometeorites) pose a more difficult problem.

Economics

With a space elevator, materials might be sent into orbit at a fraction of the current cost. As of 2000, conventional rocket designs cost about on eleven thousand U.S. dollars per kilogram for transfer to low earth or geostationary orbit. [44] Current proposals envision payload prices starting as low as $220 per kilogram. [45]

Alternatives to geostationary tether concepts

Many different types of structures ("space elevators") for accessing space have been suggested; However, As of 2004, concepts using geostationary tethers seem to be the only space elevator concept that is the subject of active research and commercial interest in space.[46]

The original concept envisioned by Tsiolkovski was a compression structure, a concept similar to a aerial mast. While such structures might reach the agreed altitude for space (100 km), they are unlikely to reach geostationary orbit (35,786 km). The concept of a Tsiolkovski tower combined with a classic space elevator cable has been suggested.[7]

Other alternatives to a space elevator include an orbital ring, space fountain, launch loop and Skyhook.

See also

- Lunar space elevator for the moon variant

- Space elevator construction discusses alternative construction methods of a space elevator.

- Space elevator safety discusses safety aspects of space elevator construction and operation.

- Space elevator economics discusses capital and maintenance costs of a space elevator.

- Space fountain

- Tether propulsion

- Launch loop

- Space gun

- Space elevator in fiction

References

Specific

- ^ Hirschfeld, Bob (2002-01-31). "Space Elevator Gets Lift". TechTV. G4 Media, Inc. Archived from the original on 2005-06-08. Retrieved 2007-09-13.

The concept was first described in 1895 by Russian author K.E. Tsiolkovsky in his "Speculations about Earth and Sky and on Vesta."

- ^ Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhooks for the Moon and Mars with Conventional Materials Hans Moravec 1978

- ^ "Space Elevator Concept". LiftPort Group. Retrieved 2007-07-28. 'COUNTDOWN TO LIFT: October 27, 2031'

- ^ David, Leonard (2002). "The Space Elevator Comes Closer to Reality".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdtate=ignored (help) '(Bradley Edwards said) In 12 years, we could be launching tons of payload every three days' - ^ "The Space Elevator". Institute for Scientific Research, Inc. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ a b "The Audacious Space Elevator". NASA Science News. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ a b c Geoffrey A. Landis and Christopher Cafarelli (1999). "The Tsiolkovski Tower Reexamined". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 52: pp. 175–180.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|other=ignored (|others=suggested) (help) - ^ Artsutanov, Yu (1960). "To the Cosmos by Electric Train" (PDF). Young Person's Pravda. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Isaacs, J. D. (1966). "Satellite Elongation into a True 'Sky-Hook'". Science. 11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ J. Pearson (1975). "The orbital tower: a spacecraft launcher using the Earth's rotational energy" (PDF). Acta Astronautica. 2: 785–799. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(75)90021-1.

- ^ Hans P. Moravec, "A Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhook," Journal of the Astronautical Sciences, Vol. 25, October-December 1977

- ^ Science @ NASA, Audacious & Outrageous: Space Elevators, September 2000

- ^ "Space Elevators: An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium".

- ^ Bradley Edwards, Eureka Scientific, NIAC Phase I study

- ^ Bradley Edwards, Eureka Scientific, NIAC Phase II study

- ^ Yu, Min-Feng (2000). "Tensile Loading of Ropes of Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes and their Mechanical Properties". Phys. Rev. Lett. 84: 5552–5555. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5552.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Min-Feng Yu, Oleg Lourie, Mark J. Dyer, Katerina Moloni, Thomas F. Kelly, Rodney S. Ruoff (2000). "Strength and Breaking Mechanism of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Under Tensile Load". Science. no. 287 (5453): pp. 637–640. doi:10.1126/science.287.5453.637. PMID 10649994.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boyle, Alan. "Space elevator contest proposed". MSNBC. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "The Space Elevator - Elevator:2010". Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "Space Elevator Ribbon Climbing Robot Competition Rules". Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "NASA Announces First Centennial Challenges' Prizes". 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Britt, Robert Roy. "NASA Details Cash Prizes for Space Privatization". Space.com. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ "Space Elevator Group to Manufacture Nanotubes". Universe Today. 2005. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

- ^ Groshong, Kimm (2006-02-15). "Space-elevator tether climbs a mile high". NewScientist.com. New Scientist. Retrieved 2006-03-05.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Miraikan Event

- ^ http://www.spaceward.org/elevator2010

- ^ The Spaceward Foundation

- ^ a b c d "Japan hopes to turn sci-fi into reality with elevator to the stars". Lewis, Leo; News International Group; accessed 2008-09-22.

- ^ "Leaving the Planet by Space Elevator". Edwards, Bradley C. and Westling, Eric A. and Ragan, Philip; Leasown Pty Ltd.; accessed 2008-09-26.

- ^ a b "The Space Elevator NIAC Phase II Final Report" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ a b c Demczyk, B.G. (2002). "Direct mechanical measurement of the tensile strength and elastic modulus of multiwalled carbon nanotubes" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-15."2–5 GPa for fibers [2,3] and up to 20 GPa for ‘whiskers’", "Depending on the choice of this surface, σT can range from E/7 to E/5 (0.14–0.177 TPa)"

- ^ Mills, Jordan (2002). "Carbon Nanotube POF". Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ 52nd Hatfield Memorial Lecture : Large Chunks of Very Strong Steel

- ^ http://www.strangehorizons.com/2003/20030714/orbital_railroads.shtml

- ^

T. Yildirim, O. Gülseren, Ç. Kılıç, S. Ciraci (2000). "Pressure-induced interlinking of carbon nanotubes". Phys. Rev. B. 62: 12648–12651. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.62.12648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "UPC Team Recens' Answer to NASA's Beam Power Space Elevator Challenge" (PDF). Polytechnic University of Catalonia. March 26, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Al Globus. "NAS-97-029: NASA Applications of Molecular Nanotechnology" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Why the Space Elevator's Center of Mass is not at GEO" by Blaise Gassend

- ^ NIAC Space Elevator Report chapter4

- ^ "[[Hans Moravec]]: SPACE ELEVATORS (1980)".

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ a b Pearson, Jerome (2005). "Lunar Space Elevators for Cislunar Space Development Phase I Final Technical Report" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Asteroid Retrieval by Rotary Rocket" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "Tapered Sling". Island One Society. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Chennai (2002-08-18). "Delayed countdown". Fultron Corporatoin. The Information Company Pvt Ltd. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ The Spaceward Foundation. "The Space Elevator FAQ". Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Bradley C. Edwards, Ben Shelef (2004). "THE SPACE ELEVATOR AND NASA'S NEW SPACE INITIATIVE" (PDF). 55th International Astronautical Congress 2004 - Vancouver, Canada. Retrieved 2007-07-28. 'At this time the space elevator is not included in the NASA space exploration program or funded in any form by NASA except through a congressional appropriation ($1.9M to ISR/MSFC)'

[Isaa66] Isaacs, J. D., A. C. Vine, H. Bradner & G. E. Bachus (1966) ‘Satellite Elongation into a True “Sky-Hook”' Science 151: 682-683.

General

- Edwards BC, Ragan P. "Leaving The Planet By Space Elevator" Seattle, USA: Lulu; 2006. ISBN 978-1-4303-0006-9 See Leaving The Planet

- Edwards BC, Westling EA. The Space Elevator: A Revolutionary Earth-to-Space Transportation System. San Francisco, USA: Spageo Inc.; 2002. ISBN 0-9726045-0-2.

- Space Elevators - An Advanced Earth-Space Infrastructure for the New Millennium [PDF]. A conference publication based on findings from the Advanced Space Infrastructure Workshop on Geostationary Orbiting Tether "Space Elevator" Concepts, held in 1999 at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama. Compiled by D.V. Smitherman, Jr., published August 2000.

- "The Political Economy of Very Large Space Projects" HTML PDF, John Hickman, Ph.D. Journal of Evolution and Technology Vol. 4 - November 1999.

- The Space Elevator NIAC report by Dr. Bradley C. Edwards

- A Hoist to the Heavens By Bradley Carl Edwards

- Ziemelis K. "Going up". In New Scientist 2001-05-05, no.2289, p.24–27. Republished in SpaceRef. Title page: "The great space elevator: the dream machine that will turn us all into astronauts."

- The Space Elevator Comes Closer to Reality. An overview by Leonard David of space.com, published 27 March 2002.

- Krishnaswamy, Sridhar. Stress Analysis — The Orbital Tower (PDF)

- LiftPort's Roadmap for Elevator To Space SE Roadmap (PDF)

- Space Elevators Face Wobble Problem: New Scientist

External links

- Elevator:2010 Space elevator prize competitions

- The Space Elevator Reference

- Audacious & Outrageous: Space Elevators

- The Economist: Waiting For The Space Elevator (June 8, 2006 - subscription required)

- CBC Radio Quirks and Quarks November 3, 2001 Riding the Space Elevator