Masculinity: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Noraalicia (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

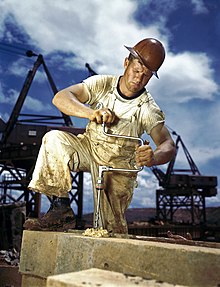

[[Image:Lewis Hine Power house mechanic working on steam pump.jpg|thumb|right|During the first half of the twentieth century, men were often associated with images of [[industrialization]]]] |

[[Image:Lewis Hine Power house mechanic working on steam pump.jpg|thumb|right|During the first half of the twentieth century, men were often associated with images of [[industrialization]]]] |

||

'''Masculinity''' is [[manly]] character |

'''Masculinity''' is [[manly]] character. It specifically describes men and boys , that is personal and human, unlike ''[[male]]'' which can also be used to describe animals, or ''[[masculine (grammar)|masculine]]'' which can also be used to describe noun classes. When ''masculine'' is used to describe men, it can have degrees of comparison—''more masculine'', ''most masculine''. The opposite can be expressed by terms such as ''unmanly'', ''[[epicene]]'' or ''effeminate''.<ref name=Roget> |

||

''[[Roget's Thesaurus|Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus]]'', 3rd. ed., [[Houghton Mifflin]], 1995. </ref> |

''[[Roget's Thesaurus|Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus]]'', 3rd. ed., [[Houghton Mifflin]], 1995. </ref> |

||

[[Cicero]] wrote that "a man's chief quality is [[courage]]."<ref> |

|||

"''Viri autem propria maxime est fortitudo''." Cicero, ''[[Tusculanae Quaestiones]]'', 1:11:18.</ref> |

|||

''[[Virility]]'' (from Latin ''[[:la:vir]]'', man) is a near-[[synonym]] for masculinity.<ref name=Roget /> |

|||

The usual [[Complementarity|complement]] of masculinity is ''[[femininity]].''<ref name=Roget /> |

The usual [[Complementarity|complement]] of masculinity is ''[[femininity]].''<ref name=Roget /> |

||

| Line 14: | Line 12: | ||

=== Ancient === |

=== Ancient === |

||

Ancient [[literature]] goes back to about 3000 BC. It includes both explicit statements of what was expected of men in [[law]]s, and implicit suggestions about masculinity in [[myth]]s involving [[god]]s and [[hero]]es. Kate Cooper, writing about ancient understandings of femininity, suggests that, "Wherever a woman is mentioned a man's character is being judged — and along with it what he stands for."<ref> |

Ancient [[literature]] goes back to about 3000 BC. It includes both explicit statements of what was expected of men in [[law]]s, and implicit suggestions about masculinity in [[myth]]s involving [[god]]s and [[hero]]es. Men throughout history have gone to meet exacting cultural standards of what is considered attractive. Kate Cooper, writing about ancient understandings of femininity, suggests that, "Wherever a woman is mentioned a man's character is being judged — and along with it what he stands for."<ref> |

||

Kate Cooper, [http://books.google.com/books?id=QVvn8vUMZdIC&pg=PA19&lpg=PA19&dq=%22wherever+a+woman+is+mentioned+a+man's+character+is+being+judged%22&source=web&ots=lYAXvJa29I&sig=LvrybebcK9gPm4PaJWe5934jD5Y ''The Virgin and The Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity'',] (Cambridge, Massachusetts: [[Harvard University Press]], 1996), p. 19.</ref> One well-known representative of this literature is the ''[[Code of Hammurabi]]'' (from about 1750 BC). |

Kate Cooper, [http://books.google.com/books?id=QVvn8vUMZdIC&pg=PA19&lpg=PA19&dq=%22wherever+a+woman+is+mentioned+a+man's+character+is+being+judged%22&source=web&ots=lYAXvJa29I&sig=LvrybebcK9gPm4PaJWe5934jD5Y ''The Virgin and The Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity'',] (Cambridge, Massachusetts: [[Harvard University Press]], 1996), p. 19.</ref> One well-known representative of this literature is the ''[[Code of Hammurabi]]'' (from about 1750 BC). |

||

*Rule 3: "If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death." |

*Rule 3: "If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death." |

||

| Line 26: | Line 24: | ||

[[Jeffrey Richards]] describes a European, "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric."<ref>Jeffrey Richards, [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bpl/cuva/1999/00000003/00000002/art00057 'From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of ‘Medieval’ Masculinity,'] ''Cultural Values'' '''3''' (1999): 213-234.</ref> Again ethics, courage and generosity are seen as characteristic of the portrayal of men in literary history. In Anglo Saxon, ''[[Beowulf]]'' and, in several languages, the legends of [[King Arthur]] are famous examples of medieval ideals of masculinity. The documented ideals include many examples of an "exaulted" place for women, in romance and [[courtly love]]. |

[[Jeffrey Richards]] describes a European, "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric."<ref>Jeffrey Richards, [http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/bpl/cuva/1999/00000003/00000002/art00057 'From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of ‘Medieval’ Masculinity,'] ''Cultural Values'' '''3''' (1999): 213-234.</ref> Again ethics, courage and generosity are seen as characteristic of the portrayal of men in literary history. In Anglo Saxon, ''[[Beowulf]]'' and, in several languages, the legends of [[King Arthur]] are famous examples of medieval ideals of masculinity. The documented ideals include many examples of an "exaulted" place for women, in romance and [[courtly love]]. |

||

==Masculine physical attributes== |

|||

== Characteristics according to Janet Saltzman Chafetz == |

|||

Some research has indicated that a number{{Clarifyme|date=February 2009}} of [[heterosexuality|heterosexual]] women may be aroused by broad chins, high cheekbones, and find large eyes as the most attractive, though there are cultural differences in those preferences. Some research has also indicated that women recognize a good body as indicative of a man of discipline and self-control. It tells a woman you can keep up with her. |

|||

Although the actual stereotypes may have remained relatively constant, the value attached to the masculine and feminine stereotypes seem to have changed over the past few decades. |

|||

Janet Saltzman Chafetz (1974, 35-36) describes seven areas of masculinity.{{full}} |

|||

#Physical — [[virile]], [[athletic]], [[strong]], [[brave]]. |

|||

#Functional — [[breadwinner]], provider for family |

|||

#Sexual — sexually aggressive, experienced, heterosexual. Single status acceptable; |

|||

#Emotional — unemotional, [[stoic]], for example, the proverb "''boys don't cry''"; |

|||

#Intellectual — [[logic]]al, [[intellectual]], [[rationality|rational]], [[objective]], practical, |

|||

#Interpersonal — [[leader]], dominating; [[disciplinarian]]; independent, free, individualistic; demanding; |

|||

#Other Personal Characteristics — [[success]]-oriented, [[ambitious]], [[aggressive]], [[proud]], [[egotistical]]; [[morality|moral]], [[trust (social sciences)|trust]]worthy; decisive, competitive, uninhibited, adventurous. |

|||

== Biology and culture == |

== Biology and culture == |

||

| Line 44: | Line 36: | ||

Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/graphic/2006/12/18/GR2006121800372.html 'The Perception of Pain',] ''Washington Post'', 19 December 2006.</ref> Therefore while masculinity looks different in different cultures, there are common aspects to its definition across cultures.<ref>[[Donald Brown]], ''[[Human Universals]]''</ref> Sometimes gender scholars will use the phrase "[[hegemony|hegemonic]] masculinity" to distinguish the most dominant form of masculinity from other variants. In the mid-twentieth century United States, for example, [[John Wayne]] might embody one form of masculinity, while [[Albert Einstein]] might be seen as masculine, but not in the same "hegemonic" fashion. |

Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, [http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/graphic/2006/12/18/GR2006121800372.html 'The Perception of Pain',] ''Washington Post'', 19 December 2006.</ref> Therefore while masculinity looks different in different cultures, there are common aspects to its definition across cultures.<ref>[[Donald Brown]], ''[[Human Universals]]''</ref> Sometimes gender scholars will use the phrase "[[hegemony|hegemonic]] masculinity" to distinguish the most dominant form of masculinity from other variants. In the mid-twentieth century United States, for example, [[John Wayne]] might embody one form of masculinity, while [[Albert Einstein]] might be seen as masculine, but not in the same "hegemonic" fashion. |

||

[[Machismo]] is a form of masculine culture. Still existing in some parts of Central and south america. |

|||

[[Machismo]] is a form of masculine culture. It includes assertiveness or standing up for one's rights, responsibility, selflessness, general code of ethics, sincerity, and respect.<ref>Mirande, Alfredo (1997). ''Hombres y Machos: Masculinity and Latino Culture'', p.72-74. ISBN 0-8133-3197-8.</ref> |

|||

Anthropology has shown that masculinity itself has [[social status]], just like wealth, [[Race (classification of human beings)|race]] and [[social class]]. In [[western culture]], for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status. Many English words such as ''virtue'' and ''virulant'' (from the Latin ''vir'' meaning ''man'') reflect this. An association with physical and/or moral [[strength]] is implied. Masculinity is associated more commonly with men than with boys. |

|||

=== |

=== Western trends === |

||

According to a paper submitted by [[Tracy Tylka]] to the [[American Psychological Association]] (APA), in contemporary America: "Instead of seeing a decrease in [[objectification]] of women in society, there has just been an increase in the objectification of |

According to a paper submitted by [[Tracy Tylka]] to the [[American Psychological Association]] (APA), in contemporary America: "Instead of seeing a decrease in [[objectification]] of women in society, there has just been an increase in the objectification of both sexes. And you can see that in the media today." Men and women restrict their food intake in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively thin body, in extreme cases leading to [[eating disorder]]s. |

||

Pressure To Be More Muscular May Lead Men To Unhealthy Behaviors<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

[[Thomas Holbrook]], also a psychiatrist, cites a recent Canadian study indicating as many as one in six of those with eating disorders were men.<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9F02EED7133EF936A15755C0A9669C8B63 Thinner: The Male Battle With Anorexia - New York Times<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

[[Thomas Holbrook]], also a psychiatrist, cites a recent Canadian study indicating as many as one in six of those with eating disorders were men.<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9F02EED7133EF936A15755C0A9669C8B63 Thinner: The Male Battle With Anorexia - New York Times<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

"Younger men who read |

"Younger men and women who read fitness and fashion magazines could be psychologically harmed by the images of perfect female and male physiques," according to recent research in the United Kingdom. Some young women and men exercise excessively in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively fit and muscular body, which in extreme cases can lead to [[body dysmorphic disorder]] or [[muscle dysmorphia]].<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/7318411.stm BBC NEWS | Health | Magazines 'harm male body image'<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.askmen.com/sports/bodybuilding/56_fitness_tip.html Muscle dysmorphia - AskMen.com<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.livescience.com/health/060815_bodyimage_men.html Men Muscle in on Body Image Problems | LiveScience<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

==Development of masculinity== |

==Development of masculinity== |

||

{{main|Masculine psychology|Gender differences}} |

{{main|Masculine psychology|Gender differences}} |

||

A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics. The process of [[sexual differentiation]] specific to the reproductive system of ''Homo sapiens'' |

A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics. The process of [[sexual differentiation]] specific to the reproductive system of ''Homo sapiens''. The [[SRY gene]] on the [[Y chromosome]], however, interferes with the process creating a female , causing a chain of events that, leads to [[testes]] formation, [[androgen]] production and a range of both natal and post-natal hormonal effects covered by the terms.[[Image:PalmercarpenterA.jpg|thumb|A construction worker in 1942.]] |

||

[[Image:PalmercarpenterA.jpg|thumb|A construction worker in 1942.]] |

|||

There is an extensive debate about how children develop [[Gender identity|gender identities]]. |

There is an extensive debate about how children develop [[Gender identity|gender identities]]. |

||

{{Original research|date=December 2007}} |

{{Original research|date=December 2007}} |

||

In many cultures displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Among men, some non-standard behaviors may be considered a sign of [[homosexuality]], |

In many cultures displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Among men, some non-standard behaviors may be considered a sign of [[homosexuality]],. Within [[sociology]] such labeling and conditioning is known as [[gender role|gender assumptions]], and is a part of [[socialization]] to better match a culture's [[mores]]. The corresponding social condemnation of excessive masculinity may be expressed in terms such as "[[machismo]]" or "[[testosterone poisoning]]." |

||

The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While [[social conditioning]] obviously plays a role, it can also be observed that certain aspects of the masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures. |

The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While [[social conditioning]] obviously plays a role, it can also be observed that certain aspects of the feminine and masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures. |

||

The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as [[behavioral genetics]], [[evolutionary psychology]], [[human ecology]] and [[sociobiology]]. All human [[culture]]s seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through [[literature]], [[costume]] and [[song]]. Some examples of this might include the epics of [[Homer]], the [[King Arthur]] tales in English, the [[Norm (philosophy)|normative]] commentaries of [[Confucius]] or biographical studies of the prophet [[Muhammad]]. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the ''[[Bhagavad Gita]]'' or [[bushido]]'s ''[[Hagakure]]''. |

The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as [[behavioral genetics]], [[evolutionary psychology]], [[human ecology]] and [[sociobiology]]. All human [[culture]]s seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through [[literature]], [[costume]] and [[song]]. Some examples of this might include the epics of [[Homer]], the [[King Arthur]] tales in English, the [[Norm (philosophy)|normative]] commentaries of [[Confucius]] or biographical studies of the prophet [[Muhammad]]. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the ''[[Bhagavad Gita]]'' or [[bushido]]'s ''[[Hagakure]]''. |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

Another term for a masculine woman is "[[Butch and femme|butch]]", which is associated with [[lesbian]]ism. "Butch" is also used within the lesbian community, |

Another term for a masculine woman is "[[Butch and femme|butch]]", which is associated with [[lesbian]]ism. "Butch" is also used within the lesbian community, without a negative connotation, but with a more specific meaning (Davis and Lapovsky Kennedy, 1989). |

||

====Pressures associated with masculinity==== |

====Pressures associated with masculinity==== |

||

Acting 'manly' among peers will often result in increased social validation or general competitive advantage.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

In 1987, Eisler and Skidmore did studies on masculinity and created the idea of 'masculine stress'. They found four mechanisms of masculinity that accompany masculine gender role often result in emotional stress. They include: |

In 1987, Eisler and Skidmore did studies on masculinity and created the idea of 'masculine stress'. They found four mechanisms of masculinity that accompany masculine gender role often result in emotional stress. They include: |

||

* the emphasis on prevailing in situations requiring |

* the emphasis on prevailing in situations requiring body and fitness |

||

* being perceived as emotional |

* being perceived as emotional |

||

* the need to feel |

* the need to feel adequate in regard to sexual matters and work |

||

* the need to repress tender emotions such as showing emotions restricted according to traditional masculine customs |

|||

====Coping strategies==== |

====Coping strategies==== |

||

Standards of masculinity cannot only create [[stress (medicine)|stress]] in themselves for some men; they can also limit these men's abilities to relieve stress. Some men appraise situations using the [[schema]] of what is an acceptable masculine response rather than what is objectively the best response. As a result men feel limited to a certain range of "approved" responses and coping strategies. |

|||

===Risk-taking=== |

===Risk-taking=== |

||

The driver fatality rate per vehicle miles driven is higher for women than for men.<ref>[http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/06/980618032130.htm Women |

The driver fatality rate per vehicle miles driven is higher for women than for men.<ref>[http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1998/06/980618032130.htm Women Better Drivers Than Men<?-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> men drive significantly more miles than women though, on average, so they are more likely to be involved in [[road traffic accident|motor vehicle accident]]s. But even in the narrow category of young (16-20) driver fatalities with a high blood alcohol content (BAC), a male's risk of dying is higher(!) than a female's risk at the Same BAC level! <ref>http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/98.010.PDF</ref> That is, young women drivers need to be more drunk to have the same risk of dying in a fatal accident as young men drivers. Men are in fact three times more likely to die in all kinds of accidents than women. In the United States, men make up 92% of workplace deaths, indicating either a greater willingness to perform dangerous work, or a societal expectation to perform this work.<ref>[http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/cfch0005.pdf CFOI Charts, 1992-2006<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

The reasons for this willingness to take risks are widely debated. |

The reasons for this willingness to take risks are widely debated. |

||

===Health care=== |

===Health care=== |

||

Men are |

Men are Significantly Less likely to visit their physicians to receive preventive health care examinations. American men make 134.5 million fewer physician visits than American women each year. In fact, men make only 40.8% of all physician visits. A quarter of the men who are 45 to 60, hopefully changing numbers, do not have a personal physician. Men Should go to annual heart checkups with physicians but many do not, increasing their risk of death from [[heart disease]]. Men between the ages of 25 and 65 are in fact four times more likely to die from [[cardiovascular disease]] than women. Men are more likely to be diagnosed in a later stage of a [[terminal illness]] because of their reluctance to go to the doctor. |

||

Reasons men give for not having annual physicals and not visiting their physician include [[fear]], [[denial]], [[embarrassment]], a dislike of situations out of their control, or not worth the time or cost. |

Reasons men give for not having annual physicals and not visiting their physician include [[fear]], [[denial]], [[embarrassment]], a dislike of situations out of their control, or not worth the time or cost. |

||

| Line 100: | Line 88: | ||

Research on beer commercials by [[Lance Strate|Strate]] (Postman, Nystrom, Strate, And Weingartner 1987; Strate 1989, 1990) and by Wenner (1991) show some results relevant to studies of masculinity. In beer commercials, the ideas of masculinity (especially risk-taking) are presented and encouraged. The commercials often focus on situations where a man is overcoming an obstacle in a group. The men will either be working hard or playing hard. For instance the commercial will show men who do physical labor such as construction workers, or farm work, or men who are [[cowboy]]s. Beer commercials that involve playing hard have a central theme of mastery (over nature or over each other), risk, and adventure. For instance, the men will be outdoors [[fishing]], [[camping]], playing sports, or hanging out in [[bar (establishment)|bars]]. There is usually an element of [[danger]] as well as a focus on movement and speed. This appeals to and emphasizes the idea that real men overcome danger and enjoy speed (i.e. fast cars/driving fast). The bar serves as a setting for test of masculinity (skills like [[billiards|pool]], [[physical strength|strength]] and drinking ability) and serves as a center for male socializing. |

Research on beer commercials by [[Lance Strate|Strate]] (Postman, Nystrom, Strate, And Weingartner 1987; Strate 1989, 1990) and by Wenner (1991) show some results relevant to studies of masculinity. In beer commercials, the ideas of masculinity (especially risk-taking) are presented and encouraged. The commercials often focus on situations where a man is overcoming an obstacle in a group. The men will either be working hard or playing hard. For instance the commercial will show men who do physical labor such as construction workers, or farm work, or men who are [[cowboy]]s. Beer commercials that involve playing hard have a central theme of mastery (over nature or over each other), risk, and adventure. For instance, the men will be outdoors [[fishing]], [[camping]], playing sports, or hanging out in [[bar (establishment)|bars]]. There is usually an element of [[danger]] as well as a focus on movement and speed. This appeals to and emphasizes the idea that real men overcome danger and enjoy speed (i.e. fast cars/driving fast). The bar serves as a setting for test of masculinity (skills like [[billiards|pool]], [[physical strength|strength]] and drinking ability) and serves as a center for male socializing. |

||

Men drink more alcohol than women, often engaging in risky behavior such as [[binge drinking]].<ref>{{cite news |

|||

|title=Are Women More Vulnerable to Alcohol's Effects? |

|||

|author=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

|author=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

||

|work=Alcohol Alert |

|work=Alcohol Alert |

||

| Line 110: | Line 97: | ||

|authorlink=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

|authorlink=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

According to a study done by Rorabaugh, college men are among the heaviest drinkers in American society. In exchange for taking the risk presented, college men receive acceptance from their peers. Not only is alcohol in itself a risk in these men's lives, but some college rituals and traditions expect men to mix danger while they have consumed alcohol. In American colleges, young men view their |

According to a study done by Rorabaugh, college women and men are among the heaviest drinkers in American society. In exchange for taking the risk presented, college women and men receive acceptance from their peers. Not only is alcohol in itself a risk in these women and men's lives, but some college rituals and traditions expect women and men to mix danger while they have consumed alcohol. In American colleges, young women and men view their development in a moment that is socially dominated by alcohol. |

||

==Footnotes== |

==Footnotes== |

||

Revision as of 08:24, 12 February 2009

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. |

Masculinity is manly character. It specifically describes men and boys , that is personal and human, unlike male which can also be used to describe animals, or masculine which can also be used to describe noun classes. When masculine is used to describe men, it can have degrees of comparison—more masculine, most masculine. The opposite can be expressed by terms such as unmanly, epicene or effeminate.[1]

The usual complement of masculinity is femininity.[1]

Literature review

Ancient

Ancient literature goes back to about 3000 BC. It includes both explicit statements of what was expected of men in laws, and implicit suggestions about masculinity in myths involving gods and heroes. Men throughout history have gone to meet exacting cultural standards of what is considered attractive. Kate Cooper, writing about ancient understandings of femininity, suggests that, "Wherever a woman is mentioned a man's character is being judged — and along with it what he stands for."[2] One well-known representative of this literature is the Code of Hammurabi (from about 1750 BC).

- Rule 3: "If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death."

- Rule 128: "If a man takes a woman to wife, but has no intercourse with her, this woman is no wife to him."[3]

Scholars suggest integrity and equality as masculine values in male-male relationships,[4] and virility in male-female relationships. Legends of ancient heroes include: The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Such narratives are considered to reveal qualities in the hero that inspired respect, like wisdom or courage, the knowing of things that other men do not know and the taking of risks that other men would not dare.

Medieval

Jeffrey Richards describes a European, "medieval masculinity which was essentially Christian and chivalric."[5] Again ethics, courage and generosity are seen as characteristic of the portrayal of men in literary history. In Anglo Saxon, Beowulf and, in several languages, the legends of King Arthur are famous examples of medieval ideals of masculinity. The documented ideals include many examples of an "exaulted" place for women, in romance and courtly love.

Masculine physical attributes

Some research has indicated that a number[clarification needed] of heterosexual women may be aroused by broad chins, high cheekbones, and find large eyes as the most attractive, though there are cultural differences in those preferences. Some research has also indicated that women recognize a good body as indicative of a man of discipline and self-control. It tells a woman you can keep up with her.

Although the actual stereotypes may have remained relatively constant, the value attached to the masculine and feminine stereotypes seem to have changed over the past few decades.

Biology and culture

Masculinity has its roots in genetics (see gender).[6][7] Therefore while masculinity looks different in different cultures, there are common aspects to its definition across cultures.[8] Sometimes gender scholars will use the phrase "hegemonic masculinity" to distinguish the most dominant form of masculinity from other variants. In the mid-twentieth century United States, for example, John Wayne might embody one form of masculinity, while Albert Einstein might be seen as masculine, but not in the same "hegemonic" fashion.

Machismo is a form of masculine culture. Still existing in some parts of Central and south america.

Western trends

According to a paper submitted by Tracy Tylka to the American Psychological Association (APA), in contemporary America: "Instead of seeing a decrease in objectification of women in society, there has just been an increase in the objectification of both sexes. And you can see that in the media today." Men and women restrict their food intake in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively thin body, in extreme cases leading to eating disorders. Pressure To Be More Muscular May Lead Men To Unhealthy Behaviors]</ref> Thomas Holbrook, also a psychiatrist, cites a recent Canadian study indicating as many as one in six of those with eating disorders were men.[9]

"Younger men and women who read fitness and fashion magazines could be psychologically harmed by the images of perfect female and male physiques," according to recent research in the United Kingdom. Some young women and men exercise excessively in an effort to achieve what they consider an attractively fit and muscular body, which in extreme cases can lead to body dysmorphic disorder or muscle dysmorphia.[10][11][12]

Development of masculinity

A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics. The process of sexual differentiation specific to the reproductive system of Homo sapiens. The SRY gene on the Y chromosome, however, interferes with the process creating a female , causing a chain of events that, leads to testes formation, androgen production and a range of both natal and post-natal hormonal effects covered by the terms.

There is an extensive debate about how children develop gender identities.

This article possibly contains original research. (December 2007) |

In many cultures displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Among men, some non-standard behaviors may be considered a sign of homosexuality,. Within sociology such labeling and conditioning is known as gender assumptions, and is a part of socialization to better match a culture's mores. The corresponding social condemnation of excessive masculinity may be expressed in terms such as "machismo" or "testosterone poisoning."

The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While social conditioning obviously plays a role, it can also be observed that certain aspects of the feminine and masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures.

The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as behavioral genetics, evolutionary psychology, human ecology and sociobiology. All human cultures seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through literature, costume and song. Some examples of this might include the epics of Homer, the King Arthur tales in English, the normative commentaries of Confucius or biographical studies of the prophet Muhammad. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the Bhagavad Gita or bushido's Hagakure. ]</ref> men drive significantly more miles than women though, on average, so they are more likely to be involved in motor vehicle accidents. But even in the narrow category of young (16-20) driver fatalities with a high blood alcohol content (BAC), a male's risk of dying is higher(!) than a female's risk at the Same BAC level! [13] That is, young women drivers need to be more drunk to have the same risk of dying in a fatal accident as young men drivers. Men are in fact three times more likely to die in all kinds of accidents than women. In the United States, men make up 92% of workplace deaths, indicating either a greater willingness to perform dangerous work, or a societal expectation to perform this work.[14]

The reasons for this willingness to take risks are widely debated.

Health care

Men are Significantly Less likely to visit their physicians to receive preventive health care examinations. American men make 134.5 million fewer physician visits than American women each year. In fact, men make only 40.8% of all physician visits. A quarter of the men who are 45 to 60, hopefully changing numbers, do not have a personal physician. Men Should go to annual heart checkups with physicians but many do not, increasing their risk of death from heart disease. Men between the ages of 25 and 65 are in fact four times more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than women. Men are more likely to be diagnosed in a later stage of a terminal illness because of their reluctance to go to the doctor.

Reasons men give for not having annual physicals and not visiting their physician include fear, denial, embarrassment, a dislike of situations out of their control, or not worth the time or cost.

Media encouragement

According to Arran Stibbe (2004), men's health problems and behaviors can be linked to the socialized gender role of men in our culture. In exploring magazines, he found that they promote traditional masculinity and claims that, among other things, men's magazines tend to celebrate "male" activities and behavior such as admiring guns, fast cars, sexually libertine women, and reading or viewing pornography regularly. In men's magazines, several "ideal" images of men are promoted, and that these images may even entail certain health risks.

Alcohol consumption behavior

Research on beer commercials by Strate (Postman, Nystrom, Strate, And Weingartner 1987; Strate 1989, 1990) and by Wenner (1991) show some results relevant to studies of masculinity. In beer commercials, the ideas of masculinity (especially risk-taking) are presented and encouraged. The commercials often focus on situations where a man is overcoming an obstacle in a group. The men will either be working hard or playing hard. For instance the commercial will show men who do physical labor such as construction workers, or farm work, or men who are cowboys. Beer commercials that involve playing hard have a central theme of mastery (over nature or over each other), risk, and adventure. For instance, the men will be outdoors fishing, camping, playing sports, or hanging out in bars. There is usually an element of danger as well as a focus on movement and speed. This appeals to and emphasizes the idea that real men overcome danger and enjoy speed (i.e. fast cars/driving fast). The bar serves as a setting for test of masculinity (skills like pool, strength and drinking ability) and serves as a center for male socializing.

|author=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

|work=Alcohol Alert

|url=http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa46.htm

|date=1999-12

|publisher=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

|accessdate=2006-11-17

|authorlink=National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

}}</ref>

According to a study done by Rorabaugh, college women and men are among the heaviest drinkers in American society. In exchange for taking the risk presented, college women and men receive acceptance from their peers. Not only is alcohol in itself a risk in these women and men's lives, but some college rituals and traditions expect women and men to mix danger while they have consumed alcohol. In American colleges, young women and men view their development in a moment that is socially dominated by alcohol.

Footnotes

- ^ a b Roget’s II: The New Thesaurus, 3rd. ed., Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

- ^ Kate Cooper, The Virgin and The Bride: Idealized Womanhood in Late Antiquity, (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 19.

- ^ The Code of Hammurabi, translated by LW King, 1910.

- ^ Karen Bassi, ['Acting like Men: Gender, Drama, and Nostalgia in Ancient Greece', Classical Philology 96 (2001): 86-92.]

- ^ Jeffrey Richards, 'From Christianity to Paganism: The New Middle Ages and the Values of ‘Medieval’ Masculinity,' Cultural Values 3 (1999): 213-234.

- ^ John Money, 'The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years', Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 20 (1994): 163-77.

- ^ Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, 'The Perception of Pain', Washington Post, 19 December 2006.

- ^ Donald Brown, Human Universals

- ^ Thinner: The Male Battle With Anorexia - New York Times

- ^ BBC NEWS | Health | Magazines 'harm male body image'

- ^ Muscle dysmorphia - AskMen.com

- ^ Men Muscle in on Body Image Problems | LiveScience

- ^ http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/98.010.PDF

- ^ CFOI Charts, 1992-2006

References

- Levine, Martin P. (1998). Gay Macho. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-4694-2.

- Stibbe, Arran. (2004). "Health and the Social Construction of Masculinity in Men's Health Magazine." Men and Masculinities; 7 (1) July, pp. 31-51.

- Strate, Lance "Beer Commercials: A Manual on Masculinity" Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

Further reading

Present situation

- Arrindell, Willem A., Ph.D. (1 October 2005) "Masculine Gender Role Stress" Psychiatric Times Pg. 31

- Ashe, Fidelma (2007) The New Politics of Masculinity, London and New York: Routledge.

- Burstin, Fay "What's Killing Men". Herald Sun (Melbourne, Australia). October 15 2005.

- Canada, Geoffrey "Learning to Fight" Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

- Raewyn Connell: Masculinities (as Robert W. Connell), Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995 ISBN 0-7456-1469-8

- Courtenay, Will "Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health" Social Science and Medicine, yr: 2000 vol: 50 iss: 10 pg: 1385–1401

- bell hooks, We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, Taylor & Francis 2004, ISBN 0415969271

- Levant & Pollack (1995) A New Psychology of Men, New York: BasicBooks

- Juergensmeyer, Mark (2005): Why guys throw bombs. About terror and masculinity (pdf)

- Kaufman, Michael "The Construction of Masculinity and the Triad of Men's Violence". Men's Lives Kimmel, Michael S. and Messner, Michael A. ed. Allyn and Bacon. Boston, London: 2001

- Mansfield, Harvey. Manliness. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0300106645

- Robinson, L. (October 21 2005). Not just boys being boys: Brutal hazings are a product of a culture of masculinity defined by violence, aggression and domination. Ottawa Citizen (Ottawa, Ontario).

- Stephenson, June (1995). Men are Not Cost Effective: Male Crime in America. ISBN 0-06-095098-6

- Williamson P. "Their own worst enemy" Nursing Times: 91 (48) 29 November 95 p 24-7

- Wray Herbert "Survival Skills" U.S. News & World Report Vol. 139 , No. 11; Pg. 63 September 26 2005

- "Masculinity for Boys"; published by UNESCO, New Delhi, 2006;

History

- Michael Kimmel, Manhood in America, New York [etc.]: The Free Press 1996

- A Question of Manhood: A Reader in U.S. Black Mens History and Masculinity, edited by Earnestine Jenkins and Darlene Clark Hine, Indiana University press vol1: 1999, vol. 2: 2001

- Gary Taylor, Castration: An Abbreviated History of Western Manhood, Routledge 2002

- Klaus Theweleit, Male fantasies, Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 1987 and Polity Press, 1987

- Peter N. Stearns, Be a Man!: Males in Modern Society, Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1990

External links

Bibliographic

- The Men's Bibliography, a comprehensive bibliography of writing on men, masculinities, gender and sexualities, listing over 16,700 works. (mainly from a constructionist perspective)

- Boyhood Studies, features a 2200+ bibliography of young masculinities.

Other

- The ManKind Project of Chicago, supporting men in leading meaningful lives of integrity, accountability, responsibility, and emotional intelligence

- XYonline, on men and gender issues. Includes over 180 articles on men, gender, masculinity and sexuality, and categorised links to 560 websites.

- NIMH web pages on men and depression, talks about men and their depression and how to get help.

- Article entitled "Wounded Masculinity: Parsifal and The Fisher King Wound" The symbolism of the story as it relates to the Wounded Masculinity of Men by Richard Sanderson M.Ed., B.A.