Talk:Monty Hall problem: Difference between revisions

Heptalogos (talk | contribs) |

Rick Block (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 3,522: | Line 3,522: | ||

:: No, that is why I said, 'for any reasonable interpretation of the problem'. Note also that this approach is already used in the article in the lead section. [[User:Martin Hogbin|Martin Hogbin]] ([[User talk:Martin Hogbin|talk]]) 14:58, 15 February 2009 (UTC) |

:: No, that is why I said, 'for any reasonable interpretation of the problem'. Note also that this approach is already used in the article in the lead section. [[User:Martin Hogbin|Martin Hogbin]] ([[User talk:Martin Hogbin|talk]]) 14:58, 15 February 2009 (UTC) |

||

:As far as I can tell, where we may be headed here (rare in math articles) is to treat this as a case where different sources (not different editors!) have different opinions and scrupulously follow [[WP:NPOV]]. It is not within Wikipedia's purview to take sides. This would suggest a longer solution section, structured like: |

|||

::''Various published sources treat the Monty Hall problem in different ways and present different solutions.'' |

|||

::''An easily understood simple solution (need a specific high quality reference) is ...'' |

|||

::''vos Savant's solution (reference Parade) is ...'' |

|||

::''A rigorous mathematical solution (reference both Morgan et al. and Gillman) is ...'' |

|||

::''A solution based on Bayes theorem is ...'' (and we'd move the Bayes solution back to the expanded Solution section). |

|||

:These should probably flow from easiest to understand to harder to understand, and say what the sources say (without adding our own editorial spin). The question then becomes how many solutions are worth including and what sources would we use. -- [[user:Rick Block|Rick Block]] <small>([[user talk:Rick Block|talk]])</small> 17:26, 15 February 2009 (UTC) |

|||

== 3rd Party Input == |

== 3rd Party Input == |

||

Revision as of 17:26, 15 February 2009

| This is the talk page for discussing changes to the Monty Hall problem article itself. Please place discussions on the underlying mathematical issues on the Arguments page. If you just have a question, try Wikipedia:Reference desk/Mathematics instead. |

| Statistics Unassessed | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Monty Hall problem is a featured article; it (or a previous version of it) has been identified as one of the best articles produced by the Wikipedia community. Even so, if you can update or improve it, please do so. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| This article appeared on Wikipedia's Main Page as Today's featured article on July 23, 2005. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mathematics FA‑class Low‑priority | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Archives |

|---|

Very important topic

{{technical (expert)}}

{{technical}}

The below suggested simple "frequency" solution should replace the current confusing conditional probability solution

See discussion further down for reasons why it should replace the current solution.

- Since these have had plenty of expert attention, I am going to disable the templates. — Carl (CBM · talk) 12:16, 16 September 2008 (UTC)

Summary and Solution

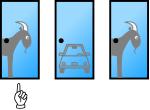

There are three doors. Two doors have a goat behind them and one door has a car behind.

(Remember goat is bad and car is good)

1) Choose one door

2) Game host opens one door containing a goat

3) Do you change door?

For example:

| Door 1 | Door 2 | Door 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Goat | Goat | Car |

Now you have two opions: Not switch or Switch

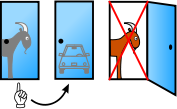

Not switch

| pick | show | outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | lose |

| 2 | 1 | lose |

| 3 | 2 or 1 | win |

If you do not switch the probability of winning is 1/3

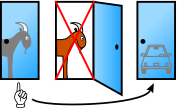

Switch

| pick | show | outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | win |

| 2 | 1 | win |

| 3 | 2 or 1 | lose |

If you switch the probability of winning is 2/3

You should therefore choose to switch doors

Note that there also exist an simpler and more elegant solution to the above problem.

From above we know that the probability of winning if we do not switch doors is 1/3.

We also know that we only have two options: Not switch or Switch

This means that:

P(switch) + P(not switch) = 1

which means that

P(switch) = 1 - P(not switch)= 1 - 1/3 = 2/3

Which is the same solution we had previously

tildes ( 82.39.51.194 (talk) 10:40, 17 August 2008 (UTC) )

I propose a very compact, straightforward solution with no mention of probability per se. The problem is, in fact, simple so we should treat it that way. After reading most of this discussion and some of the references about how to explain it in an understandable way, I've yet to see the following type of explanation.

- The problem is easy to solve - every time the game is played, one of two sequences occur:

- A)Contestant picks a door that has the car behind it; host opens one of the other doors revealing a goat; behind the remaining door is the remaining goat.

- B)Contestant picks a door that has a goat behind it; host opens the other door with a goat behind it; behind the remaining door is the car.

- Sequence A happens 1 time in 3, so, doing the math, sequence B happens 2 times in 3.

- Stickers win in sequence A and switchers win in sequence B.

- I told you it was easy.

Millbast5 (talk) 22:03, 17 September 2008 (UTC)

- Hang on a second.

- Not switch

pick show outcome 1 2 lose 2 1 lose 3 2 or 1 win

- 3 win? 3 is the goat, which is a known lose... Did I miss something? And this seems to presume knowing the outcome. If I pick 2, & switch, & 2 is the winning door, how, exactly, is this a win? TREKphiler hit me ♠ 05:36, 22 October 2008 (UTC)

Yes you are missing something and that is your brain! :-) Door 1 & 2 are goats —Preceding unsigned comment added by 92.41.207.32 (talk) 10:42, 6 February 2009 (UTC)

Repetitive new solution section

I've undone this change twice. It renames the existing "Solution" section as "Discussion" and adds an additional "Solution" section that basically repeats what's in the existing Solution section - without references, and with a variety of style issues per WP:MOS (such as directly addressing the reader). If there's some shortcoming in the current Solution section please say what it is and we can work on addressing the concern. -- Rick Block (talk) 18:57, 14 August 2008 (UTC)

- I've undone it myself too, and it's back. Can we perhaps lock the article until this user responds in the talk page?The Glopk (talk) 14:13, 15 August 2008 (UTC)

--

The problem I have with your so called solution section is that it is general confussing!

You are confussed, your glossy matrix and tree are confussed. It is not about where the car is !! The solution will look the same irregardles. It is a question whether you choose to switch or not and which door the contestant choose.

The whole point of the Montey hall excercice is to answer the question wheter you switch or not and still you refuse to take that into account !

Therefor you should divide your matrix it into

Switch

Not switch

and then review

1)all the possible doors the contestant can choose

2)the response of the host

3)the outcome of such a choice

Your original matrix might be glossy and fancy but regret to inform you that it is inaccurate

It is better if you put your glossy matrix under the section "Sources of confusion"

I can also inform you that I am going to change back my solution until you either, stop removing my solution or redesign your matrix.

Ps I found it quite strange that I have to fight for such an obvious point ! It just reaffirm the notion that wikipedia is good in theory but does not work in practice. Now you have to fight a war with every moron with a computer ! Where are the credentials, expertise and self critic ? Just because you have a computer doesn mean that you are an expert !

I have attached the original post

tildes ( 82.39.51.194 (talk) 10:40, 17 August 2008 (UTC) )

Discussion

—Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.39.51.194 (talk) 08:35, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- The existing "solution" section is clearer than the above explanation. Cretog8 (talk) 15:04, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- The solution proposed above keeps the arrangement of goats and car the same and varies the player's initial pick rather than keeping the player's initial pick the same and varying the location of the car. Both of these approaches simplify the actual 9 cases (or 18 assuming the goats can be distinguished) down to three to better show the 2/3 probability of winning. In the rest of the article (in particular, in the Bayesian analysis section) the player's pick is kept as door 1 rather than the alternative approach of examining all picks given a single arrangement of goats and cars - and this approach is the most commonly presented in the cited references (and matches the presentation of the problem published in the vos Savant Parade column).

- Another reason this approach is used is that the problem as generally presented can be considered a conditional probability problem given both a specific initial pick and a specific door the host has opened. This interpretation of the problem (see the Morgan et al reference) is discussed in the last two paragraphs of the solution section and involves examining the situation after the player's initial pick and given which door the host opens. Initially using the approach where the goat/car configuration is constant but the player's pick varies makes the connection to this conditional analysis extremely difficult to see.

- The solution section was actually changed fairly recently to use the "fixed pick, varying car location" approach (rather than the "fixed configuration, varying pick" approach) to be consistent with the majority of the references and with the rest of the article. We can certainly discuss whether including the alternative solution is worthwhile, however given that they are effectively equivalent (both relying on a "without loss of generality" assumption), and that most sources use the "fixed pick, varying car location" approach, and that the approach currently used easily extends to the conditional analysis, and that the article is quite long already, I don't think you'll find much support for including this alternate solution. -- Rick Block (talk) 19:14, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

I dont agree with what you are saying ! It is about presenting an easy to understand and approachable article. as of now none of this is taking place. Who gives a crap about "keeping the player's initial pick the same and varying the location of the car". That is not what the Monty Hall problem is about. The sooner you will realize this the better of this article will be! You need to keep the most critical stuff and just remove everything ells ! Howevere I am starting to lose interest in all this bull crap ! This is all about you ! You have written something that you protect like hamster. This is exacly the reason why wikipedia will never gain any credential in academic circles because it is not about the optimal soluton but rather individual ego! —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.39.51.194 (talk) 19:53, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- Please 82.39.51.194, no personal attacks. Feel free to discuss your displeasure and/or disagreement with the article but refrain from attacking the editors. -hydnjo talk 20:41, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

yes, I agree no personal attacks! It is just that I get so frustrated when the solution is staring them in the face and they still refuse to accept it because they are biased towards their own writing (which apparently is a lot). Just because someone wrote something first doesn't mean that such a person has the right to "validate" (oohh daddy please can I) or delete everything that comes after. You seam to have a lot of rules! Dont you have a rule for that? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.39.51.194 (talk) 21:26, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- There is indeed a rule for that: WP:OWN says that nobody should behave as if they "own" a particular article. I've put a welcome message at your talk page which you can look over to find out more stuff. All the same, you have to have some humility, too, and accept that maybe the reason your suggestions aren't being implemented is because several people don't think they're an improvement. Cretog8 (talk) 22:47, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- As a Featured (July 23, 2005) and high-traffic (392 thousand views, Jan-Jun '08) and heavily edited (500 edits to date in '08) article, there are lots of inputs for further improvement. The article has been scrutinized by the community at large in a process called Featured article review and the criticisms from that review have been successfully addressed so that the article meets today's FA standards. Given that bit of perspective, the article is absolutely not frozen and the editors that who are watching continue to to demonstrate (IMO) an open mind when it comes to addressing suggestions for improvement. It may be helpful to scan the archives of this talk page to gain further perspective about the responses to your suggestions. -hydnjo talk 23:26, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

- Moreover, the current version attempts to stay as close as possible to the academic references. Have you read the references that are in the article and do you have other references that present the solution using your preferred approach? Even if you're not going to respond to the explanation above about why the current approach is used, a suggestion that you find "so and so's explanation from this paper or book" easier to understand would be received quite differently from "I like my explanation better". -- Rick Block (talk) 23:33, 16 August 2008 (UTC)

With all due respect I am not convinced that you (any of you) fully understand the rules of the Monty Hall Game.

1) First the allocation of goats and the car is taking place (remains fixed for the rest of the game).

2) Then the contestant choose one door.

Your "fixed pick, varying car location" approach totaly contradict this line of reasoning. The location of the car IS NOT changing. The allocation is stationary, it does NOT change over the period of the game. Again the first thing that happens is the allocation of the car. Again that location remaine FIXED for the ENTIRE game. But still you in insist like some stubborn child that the location is varying. It is NOT ! and it never will be ! The Monty Hall game is a SEQUENTIAL GAME which means that you CAN NOT just switch around the location of the car based upon your preferences in a later stage of the game. This means that the ONLY valid way of approaching this is the way I have put forward which means that you keep the allocation fixed and you evaluate each pick individually (the pick, the game show respons, and the outcome).

Also the argument that "majority of the references" do it one way isn't valid either. This is not an excercise in burping up some solution from some jerk off text book. Fine! you should have references to other articles but in the end it is about evaluating which approach is the most correct and not the least which approach is the easiest to understand. I hate to burst you bubble but the current approach dosent fulfill neither of these criterias irregardles if you have won a nobel price for the article.

Further, it is not about Bayesian statistics ! To allow Bayesian statistics to dictate how the original problem and its solution is presented is WRONG. Especially when such a solution contradict(is incorrect)the original game and the sequential steps such a game is based upon. If you want to have a section of Bayesian statistics that is fine! But you need to very carefully point out the different assumption such an analysis is based on! This is not taking place at the moment! The way I see it is that you have all been so blinded by the complexity of the Bayesian analysis that you have completely surrendered to its preachings! --82.39.51.194 (talk) 10:37, 17 August 2008 (UTC)

- Perhaps it is not clear to you what is the meaning of a clause like "Assume, without loss of generality, X.". To put it simply, it means: "I could repeat the same argument for cases W,Y,Z,etc., But since these are obviously equivalent to X, as they differ only by a change of names, I'll just write down the case for X and be done with it". For example, consider the proof of the Pythagorean theorem: the logic of the proof would be unchanged if you rotated the names of the triangle's vertexes so that A becomes B, B becomes C, and C becomes A. That is, the particular labeling of the vertexes is irrelevant to the proof. Similarly, in the analysis of the Monty Hall problem, the naming of the doors is unimportant, so long as it is kept consistent within the reasoning. Because of this, for example, the Bayesian analysis of the problem is written concisely using the "Assume, without loss of generality" clause.The Glopk (talk) 16:48, 17 August 2008 (UTC)

- (to 82.39.51.194) First, please read Wikipedia:No original research. Taken to its extreme what this policy says is that even if the preponderance of references are provably incorrect (which, just to be clear, is not at all the case here), the Wikipedia article must summarize what they say rather than presenting something we make up ourselves. Second, although you're perfectly correct about the sequencing of the problem we're talking about the probability of winning by switching, either over all iterations of the game or (in the Morgan et al interpretation) given a specific player's initial pick and the host's specific response. Also note that the Parade description of the problem specifically includes the words:

- You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?"

- If the goal is to determine the overall chance of winning by switching, over all possible scenarios, in a strict sense we should enumerate all possible car locations, player picks, and host responses (per the fully expanded decision tree as presented in Grinstead and Snell). On the other hand, from the player's point of view, the player (who doesn't know where the car is) picks a door and then the host opens a door, so following through what happens when the player picks a specific door (say #1) over all possible car locations (the approach currently in the article and in most references) is entirely sufficient. This is not varying the location of the car after the player has picked, but examining all possibilities of where the car might be to determine the probability of winning. Indeed, given the Parade version of the problem your preferred approach makes almost no sense at all (why are we considering what happens if the player picks door 2 when it's stated the player has picked door 1?). Morgan et al take this one step further, and consider only the scenario where the player has picked door 1 and the host has opened door 3 (eliminating the possibility that the car is behind door 3! - and, even in only this one case, the probability of winning by switching is still 2/3 [if the host chooses which of two goat doors to open with equal probability]).

- I suspect you're thinking the problem is asking about the probability of winning over all possible car locations, player picks, and host responses. What would your analysis be if the problem is about the chances of winning for a player who's literally initially picked door #1 followed by the host opening door #3? -- Rick Block (talk) 17:38, 17 August 2008 (UTC)

You dont seem to understand! The most critical question we should answer is NOT what happens if the contestant chooses one specific door and the the host opens another door! The problem is more general than that ! The whole point with the Monty Hall exercise is to answer the question whether or not the contestant should switch doors in GENERAL. This is also indicated in your quote

"You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?"

The word "say" that appear before the door numbers indicate to me that this is just an example. The individual case of door 1 and door 3 is not that important! It could have been any configuration! Again the important question is whether or not the contestant should switch doors in GENERAL. Also note the sequential nature of your quote. 1)first the allocation has taken place (which remain fixed for the rest of the game 2)Then the contestant choose one door. When you start to shuffle around the location of the car it CONTRADICT the sequential nature of the game. It also obscure the whole purpose of the Monty Hall exercise which is to prove that the contestant will benefit from switching doors in ANY situation not just "for a player who's literally initially picked door #1 followed by the host opening door #3? "--82.39.51.194 (talk) 08:39, 18 August 2008 (UTC)

- My points are:

- If the goal is to answer the general question then all goat/car configurations, all initial picks, and all host responses should be considered. Your approach is considering only one configuration using an assumption that the same logic pertains to all other configurations. The approach currently in the article considers only one initial pick and uses an assumption that the same logic applies to all other picks. Your assertion seems to be that the latter approach is wrong. Either one of these is valid (they are like looking at two sides of the same coin), although most references use the approach currently in the article. If you're not seeing that these approaches are fundamentally equivalent, I think it is you who is not understanding the problem. In addition the current approach is (IMO) more consistent with the form of the Parade problem statement which uses the "say No. 1" terminology (which encourages thinking through scenarios involving a given initial pick).

- Some references (e.g. Morgan et al) explicitly consider the situation at the point the player has picked a door and after the host has opened a door. Your approach makes this analysis difficult, however the current approach makes this a relatively simple extension of the analysis.

- The approach currently in the article is used because most references use it and this approach easily extends to cover the "conditional" (Morgan et al) interpretation of the problem. Even though you think the critical question is the general question, the conditional interpretation exists in the literature (the Morgan et al and Gillman references) so it is considered in the article. I'll ask again - how would you address this interpretation? -- Rick Block (talk) 19:15, 18 August 2008 (UTC)

First of all the current solution is NOT more consistent with the form of the Parade problem statement. Actually my proposed solution is MORE consistent with the Parade problem! The reason for that is that it is more logically consistent (sequential game nature which means that the location of the car remain fixed), more general (consider a larger amount of cases) and easier to understand (iteration nerver suns out of styl).

Secondly, How I would deal with the conditional interpretation? For me that is an interpretation that is not critical for the Monty Hall problem nor its solution. You can and should understand the Monty Hall problem and its solution only with the basic frequency statistics approach (without Bayesian statistics). Note that my proposed solution uses frequency which is the most consistent with the original formulation of the Mony Hall game since again

1) It DOES NOT contradict the logic and sequential nature of the original Monty Hall game. The location of the car (and the goats for that matter) remain fixed for the entire game.

The logic is intact

2) Is not based upon any prior assumtions about the door selection. what you see it what you get.

3) Does not start in the middle of the game (door selecton), again sequential nature

3) The formulation is much more general (consider a larger amount of cases)

4) Much easier to extend to alternative configurations for example D1=C,D2=G,D3=G or D1=G,D2=C,D3=C or D1=G,D2=G,D3=C

As I said previously if you want to include a section on conditional probabilities as an extra bonus you have to very carefully point out the different assumption such an analysis is based on. If you dont correctly point out such differences the Bayesian section will actualy contradict the original sequential reasong of the Monty Hall game.

1) Firstly you you need to explain that in order for a conditional probability approach to work we have to take the steep from

frequency statistics to Bayesian statistics. This means that we have to depart form the sequential nature of the problem where we

first have the allocation of the car and goats and then we we have the door selection. Now instead we are going to assume that the player already has done his door selection. In order to evaluate such a decision in the middle of the game we have to vary the location of the car. So basically we are inverting the origial order of the game. 1) door selection 2) allocation

2)Secondly you need to explain the reason for that). You need point out that Bayesian statistics in the form of conditional probabilities are based upon the assumtion of serial correlation (normal distribution with fat tails) which means that the observations are not independent. For example

- WHOA THERE!!! The above paragraph is pure nonsense. The Bayesian formulation of probability theory, based on Cox's axioms, is completely general and has been shown to be equivalent to any other standard formulation (e.g. Kolmogorov's). See the references ited in that section, e.g., E.T. Jaynes's "Probability Theory as Logic". Please do not make absurd statements to (try to) make a point. Also, please stop talking about "Bayesian statistics". There is not statistics involved in the Monty Hall problem: rather, it is purely a problem of probability theory.The Glopk (talk) 01:25, 21 August 2008 (UTC)

P(A∩B) is the probability of A and B happening

P(B) is the probability of B happening

P(A|B) is the probability of A happening given that event B has happened

Bayesian expression: P(A∩B)=P(B)*P(A|B)

When we have serial independence ( A and B are independent) then the P(A|B) expression is reduced to P(A)

Which means that our Bayesian expression is reduced to the frequency expression

P(A∩B)=P(B)*P(A)

These two explanations are important because it helps the reader to understand the some what contradicting and confussing set up! Here I am open for suggestions! Any solid and easy to understand explanations that can simplify the transition is most welcomed !

I now feel that I have put forward a solid argument why the current solution is not optimal. If you still fail to take my points into consideration I suggest that we seek outside help on the matter since otherwise we will continue this discussion for all eternity. To tell you the truth I have more productive things to do that arguing with you about these things!

--82.39.51.194 (talk) 10:50, 19 August 2008 (UTC)

- I will not go into the details of what you wrote here; others can do that much better than I can.

- First, I want to applaud your change of attitude instead of changing the article time and time again, you are now discussing the matter.

- However, you should note that you seem to be the only one arguing this point. That doesn't in itself mean you are wrong, of course; but you should appreciate the fact that many editors, some of them very well versed in this theory, have already been over this article in great detail. That in turn means you should consider the possibility that you are in fact mistaken. In your first posts here you seemed to take the stance that you were inquestionably correct, but as I said before, you have changed your attitude a bit, instead putting forward arguments to support your opinion. Kudos.

- One point that you haven't responded to yet is the tenet of no original research. The references cited in the article support the problem statement we currently use, and so far you have proposed no references to support your version. Oliphaunt (talk) 11:57, 19 August 2008 (UTC)

You are right I have to considered the possibility that I might be wrong! I have done that and the answer was that I am not!

It is not that much to wrong about! Further, the best references is the original Monty Hall game and its corresponding rules! I can probably dig up a reference on the frequency statistics approach (which I assume is my suggested approach) but I am not sure it is necessary. It is like asking for a reference for why 2+2=4. It is a simple exercise on calculating probabilities! If you find that difficult then you should probably not take on the conditional probability approach which dominates the current article ! --82.39.51.194 (talk) 13:31, 19 August 2008 (UTC)

- What you're not right about is your assertion that the current approach contradicts the sequence of the game. It absolutely follows the sequence, from the player's perspective. First two goats and a car are placed behind 3 closed doors, but the player doesn't know what is behind each door. In your solution, the configuration is given. Why doesn't the player just pick door 3 and stick with their initial choice? The reason of course is that the player does not know the configuration. In the version currently in the article, the configuration is left unknown (matching the situation from the player's point of view). The configuration is certainly fixed before the player picks a door, but the player doesn't know the configuration. What the player does know is the door he or she initially picks. The current solution, most sources, and the Parade problem description implicitly say (and the Bayesian analysis section explicitly says) "let's call the door the player picks door 1 (renumbering the doors if necessary)". The analysis proceeds given the unknown, but fixed, configuration of goats and car with the (now fixed) initial player choice. We examine all possible configurations of the goats and car not because we're moving them around after the player has picked (which would indeed violate the sequence of the game) but to enumerate all possible scenarios using the same frequency based approach your solution uses. This approach

- 1) exactly matches the player's view of the game. The location of the car is fixed, but unknown (in your solution, the car location is known but the player's pick is treated as variable - this is distinctly not the player's view and, literally shows only that switching wins with 2/3 probability if the car is behind door 3)

- 2) is not based on a specific arrangement of goats and car, which (again) matches the player's view of the game.

- 3) does not start in the middle of the game (if the current section is at all confusing in this regard, we could certainly work on clarifying it)

- 4) easily extends to the conditional analysis, without needing to switch to Bayesian logic (indeed, the current solution section includes the conditional analysis, without mentioning anything about Bayesian analysis)

- 5) considers all initial configurations (and, through renumbering of the doors, all initial picks and host responses)

- 6) is consistent with the view of the problem throughout the article (all the images and all the text consistently call the player's initial choice "door 1" and the door the host opens "door 3")

- You're quite welcome to seek outside help, although I would suggest the best help would be sources. The existing references are (as far as I know) the best, most authoritative sources on the topic of the Monty Hall problem. The existing approach follows the solution typically presented in these sources. I've said this about 3 times already, but your solution and the solution currently in the article are essentially equivalent (both rely on a "without loss of generality" assumption). Given two essentially equivalent approaches, using the one that more closely matches the references, more closely matches the player's view of the game, and more easily extends to cover the conditional analysis seems like the obvious choice. -- Rick Block (talk) 16:20, 19 August 2008 (UTC)

yeahh yeahh what ever !--82.39.51.194 (talk) 17:29, 19 August 2008 (UTC)

- I've clarified the sequencing in the Solution section. I hope this helps to address your concerns. -- Rick Block (talk) 02:54, 21 August 2008 (UTC)

I actually agree with 82.39.51.194 I also find the current article difficult to understand. I think a frequency statistic approach is easier to understand and more consistent with the original game.--92.41.172.75 (talk) 08:50, 21 August 2008 (UTC)

Suggestion to replace existing solution section

It appears 92.41.17.172 is suggesting that the current solution section be replaced with the contents from #Summary and Solution (above). My understanding was that per #Discussion (also above) we basically came to an agreement, albeit not very enthusiastic on the part of 82.39.51.194, about this. I won't repeat the discussion from above, but does anyone have anything more to say about this? -- Rick Block (talk) 18:30, 28 August 2008 (UTC)

- The proposed change (diff) replaces the existing solution with text which is less detailed, has no supporting references, and which includes less appealing figures. The existing section should remain. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 18:56, 28 August 2008 (UTC)

- I tend to agree with Rick, too, that the existing solution should remain. In my 35 years of teaching mathematics at a major university, including many, many probability courses, I've dealt with the Monty Hall problem many times in classes. What intrigues me most, though, is not so much the fact that the direct solution given seems to bother so many (perhaps because of the supposed veridical nature of the statement of the problem), but the fact that if one merely steps back and looks at the entire problem, there is a remarkably simple solution. The key to this solution is not to focus on switching but instead to focus on not switching. Choosing the strategy of not switching is tantamount to ignoring any and all extra information with the problem, and it is thus manifestly clear that:

- P(not switching) = 1/3

- and thus we have

- P(switching) = 1 - P(not switching) = 2/3.

- It uses nothing more than P(A) + P(not A) = 1. This is no more (and perhaps a lot less) counterintuitive than all the rest of the considerations which focus directly on choosing the switching option. I have always given perfect marks for this elegant solution and wonder why it is not mentioned in the article. Focussing on the switching strategy directly involves something like a probability tree or other construct (entailing conditional probability), fraught with potholes that can trap or fool the not-so-careful reader.

- Some of the most elegant solutions to problems in mathematics arise by looking at such problems from a different perspective. This is just one such example. -- Chuck (talk) 19:29, 28 August 2008 (UTC)

- Wait a minute. The expression P(A) + P(not A) = 1 refers to set complementation in a universal set - which has probability 1. And the not-switch strategy is not the complement of the set consisting of the switch strategy in the universe consisting of all possible strategies. For one thing, if there a two strategies there an infinite number of mixed strategies in that universe. While it is true that the probability of winning by switching plus the probability of winning by not switching is 1, it is something that you have to demonstrate by analyzing the problem. Its not hard but it sure doesn't follow from the tautology given. Just think, changing the name of the not-switch strategy to 'sticking strategy' sends the argument down the tubes.

- In this particular game, the contestant always has the opportunity to switch so the switch strategy and the not-switch strategy always end up selecting two different doors and since the the other door is open and showing a goat, the car must be behind one of those two doors. Thus probability of winning by switching plus the probability of winning by not switching is 1. However in a variant of the game where the host did not always present an opportunity to switch then some of the time the switch strategy and the not switch strategy pick the same door, hence the sum of their probabilities of winning would be less than 1. Is that an example that shows P(A) + P(not A) = 1 is not true?Millbast5 (talk) 07:43, 18 September 2008 (UTC)

Chuck, my hat is off for you! I like your way of thinking.

"P(not switching) = 1/3 and P(switching) = 1 - P(not switching) = 2/3. It uses nothing more than P(A) + P(not A) = 1"

So simple but still so powerful! Only that well crafted sentence says more than the complete article in my opinion.

I think that reasoning in combination with the new suggested "frequency" solution would greatly improve the article--92.41.17.172 (talk) 20:53, 28 August 2008 (UTC)

- I don't mean to be rude, but have you read the article? The solution section says Players who choose to switch win if the car is behind either of the two unchosen doors rather than the one that was originally picked. In two cases with 1/3 probability switching wins, so the overall probability of winning by switching is 2/3 as shown in the diagram below. The diagram then shows (visually) what happens if you switch (Chuck's point is simply the inverse of this). The killer argument against this simplistic analysis (and Chuck's) is that it completely ignores the fact that the host opens a door. Why should this same argument apply both before and after the host opens a door? The initial pick is 1/3 (surely), but then the host opens a door. Why is this any different from Howie opening a case on Deal or No Deal (or would you say never take the deal because the chances of your case being the grand prize go up every time a case is opened)? I don't teach math at a major university, but this solution simply fails to address the problem (per Morgan et al.) and doesn't seem worth more than a B- (correct answer, completely inadequate reasoning). Consider three different hosts - host 1 who opens a randomly selected "goat door" if the player initially picks the car, host 2 who always opens the rightmost "goat door" if the player initially picks the car and host 3 who opens one of the unpicked doors randomly. With host 1 the correct answer is 1/3 chance of winning if you don't switch. With host 2, assuming the player stays with the initial pick (and it's door 1), the correct answer is 0 chance of winning if the host opens door 2 but 50% chance of winning if the host opens door 3. With host 3 the correct answer is 1/2 chance of winning (assuming the host didn't reveal the car). What this means is that the argument that the initial pick results in a 1/3 chance of winning is, um, not quite correct. If you don't also consider how the host selects what door to open the answer may (coincidentally) end up with the right answer (if it's host 1) but this is fundamentally a coincidence. Given any possible host behavior the average chance of winning if you don't switch is 1/3, but if you pay attention to which door the host opens (and how the host chooses to open doors) the chances of winning by staying are anywhere from 0 to 50% depending on which door the host opens. The point is the real solution has to include a consideration of how the host chooses which door to open. If it doesn't, then the answer applies regardless of which host we're talking about (host 1, host 2, or host 3) - i.e. you arrived at the right numerical answer but your reasoning is faulty. -- Rick Block (talk) 04:45, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- Sorry, Rick, but you are being rude (which is out of place here) and it seems you have been very much caught up in the veridical nature of the posed problem. Yes, I have indeed read the article, and it beats around the bush with various possible host actions (which is another matter that I'm not addressing) ... but of course I am observing the generally agreed on rule that says the host always opens a goat door different from the door chosen by the contestant. What you don't see is that there are two and only two options which under the host assumption exhaust all possibilities: (A) be obstinate (not switching no matter what is shown) or (not A) always switch when a door (different from the one selected by the contestant) showing a goat is opened. While (not A) has all the folderal about choosing to switch), option (A) does not (if you just think about it for a moment). Moreover, (A) union (not A) is the entire event space, so P(A) + P(not A) = 1. And since P(A) is manifestly eequal to 1/3, P(not A) = 2/3.

- You complain that my solution ignores the fact that the host opens a door showing a goat. Note that it makes no difference in the outcome if the host opens either of the doors not initially selected. In the obstinate case (never switch no matter what is opened) the probability of winning the car is 1/3. If the contestant has initially chosen a goat door and her strategy is always to switch, then no matter which of the other two doors is opened, she will always with the car by switching to the opened door if it reveals a car or to the other closed door if it reveals a goat.

- In either of these two scenarios, the problem you and many have is in realizaing that (always switching) and (never switching) exhaust all possibilities. That is precisely where the problem seems like a (veridical) paradox ... and that is why the solution I give is so elegant and, at first glance, seems that it must be wrong - even though it is completely correct.

- I am reminded how, in teaching how to find areas of regions to students, we tell them that one way is to decompose the region into simpler regions and add up the areas of the pieces. Then we watch the solutions come in for a problem such as: find the area of the shaded region shown - which is nothing more than a large rectangle with a smaller rectangle removed - and students slavishly decompose the region into four rectangles, compute the area of each, and add them up, correctly of course - but completely missing the obvious solution to subtract the area of the smaller rectangle from that of the enclosing rectangle! Too bad people can't think outside the box or (in this case) inside the box.

- People's dogged insistence that the result for never switching has something to do with opening a different door from the one selected is a bit like this, the only point to the problem is to see that since the host opens a different door from that chosen by the contestant, then the obstinate and always switch options are discjoint and do indeed exhaust all possibliities.

- Oh well, some people look at a sphere and see perfection - others look at one and see a snowball and duck for cover. -- Chuck (talk) 14:11, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- Sorry for the rudeness. However, see below as well. -- Rick Block (talk) 15:26, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

ha, ha. I and many with me prefer Chuck's simple solution plus 82.39.51.194 "frequency" solution anyday over that lengthy and confused outburst by Rick Block!

There are no such thing as host-1,host-2 and host-3. The only host that exist is host-1 = Random selection of "goat door". Why would I consider an example that does not apply?

With all due respect there might be a reason for why you are not teaching math at a major university.

--92.41.46.220 (talk) 09:06, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- Respect acknowledged, however your reasoning is still inadequate. Yes host 1 is our host, but there's nothing in the simple solution that makes use of this fact. Assume for the moment we're talking about host 3 (makes it more like Deal or No Deal), not host 1. The same simple argument can be used, but in this case this argument results in an incorrect solution. The flaw is the implied claim that because P(not switching) = 1/3 when the player initially selects a door it remains so after the host opens a door, i.e. that how the host chooses to open a door is "extra information" that can be ignored. Not so.

- You have to at least explicitly say that P(not switching) doesn't change when the host (our host, host 1) opens a door because of the constraints on the host's behavior, but then the question becomes how do you know this? Asserting it to be true with no reasoning doesn't seem sufficient.

- If you have access to it, please read the Morgan et al. paper. This paper distinguishes host 1 from host 2 which is a much more subtle distinction than the difference between host 1 and host 3. With host 2, the average chance of winning by not switching (ignoring which door the host opens) is 1/3 - just like host 1. However, with host 2 there are two distinct probabilities depending on whether the host opens the rightmost or leftmost door. If the host opens the rightmost door (which he does unless the car is behind it) the chance is 1/2. If the host opens the leftmost door (which he does only when the car is behind the rightmost door) the chance is 0 (of winning by not switching). You can in some sense say the probability of winning by not switching in this case is 1/3, however the probability for any given player (with knowledge of which door the host opens) is either 0 or 1/2.

- So, back to the article. I believe the solution as stated is as simple as possible without being too simple. -- Rick Block (talk) 15:26, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

I also agree with 82.39.51.194 and 92.41.46.220. I think we have consensus now to change the solution section!

--Pello-500 (talk) 13:51, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- It appears that Chuck actually doesn't agree with your change;

- It's incredibly obvious that Pello-500 is just a new account created by 92.41.

- If you're not interested in engaging in serious discussion here, please stop editing the article. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 14:00, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- In addition to edit warring over the article, Pello/92.41/82.39 also erased my comment calling him on it. I've restored it above. Note that he had originally (and erroneously) claimed that Chuck had agreed with his position. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 21:43, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

I also agree with 82.39.51.194 and 92.41.46.220. The frequency solution is most optimal.--84.92.246.30 (talk) 17:26, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

RfC: New or old solution section?

The new suggested "frequency" + Chuck's solution is easier to understand. Current editors refuse to accept this due to ownership. They won't let anyone edit the article !

- Initial thought - if I understand correctly the question is not about what the actual solution is, that is agreed, but it is about the best way to explain it. From my experience different people have different way of looking at things. When I am trying to get to grips with a probability problem I usually find that one particular way of looking at it helps me to get it. The may not be the way that helps other people. My suggestion, therefore, is to have both solutions. Maybe the second could be added under the heading 'Another way to understand the solution'. Martin Hogbin (talk) 17:56, 29 August 2008 (UTC)

- Disagree, please leave the old solution. The new proposed "frequency" solution is poorly written and referenced. Chuck's solution is just the "naive Bayes" one (uniform prior on the host behavior). As remarked by Rich Block, the "old" solution section, i.e. the one that passed the F.A. review, offers a more comprehensive treatment that is supported by the refrences and does cover more sophisticated host behaviors.The Glopk (talk) 00:29, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- My suggestion as to what should be done depends on what people believe that the purpose of this article is. For example, is the purpose purely to consider the problem academically and with some degree of rigor or is there a secondary function of explaining to as many readers as possible what the solution is and why in a way that makes sense to them. Martin Hogbin (talk) 08:53, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- I don't know if it's necessary to repeat it, but in case someone doesn't read the section above, I'll note that the proposed replacement section is formatted poorly, lacks references, and contains less explanatory text (both quality and quantity) than the proposed replacement. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 17:48, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

Can I make sure that I now understand what the current debate is about? Some editors want to keep the page as it is but recognise that there is a rather subtle problem with it. Others wish to replace it with a more rigorous approach which some feel has been badly presented and is not necessary. Martin Hogbin (talk) 09:39, 31 August 2008 (UTC) On a second look at things I can see that I got that wrong, I was confusing the current dispute with and earlier discussion that Rick pointed me to.Martin Hogbin (talk) 15:01, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

Now that I have some idea of what is going on here, I can give my views on the current dispute. I do not think that the current solution should be replaced with the proposed one. However, I do think that it is more natural to have a fixed car position and vary the pick, but I also understand the reasons that the solution is the way that it is. I do have some criticisms of the article as it is and hopefully I will have some suggestions for improvements, but scrapping what has been done and replacing it with the proposed replacements not the way to improve in my opinion. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:08, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

I'm in favour of including both solutions. Because one method, to quote, "is formatted poorly, lacks references, and contains less explanatory text" is not grounds to remove it altogether, but to bring it up to standards. If we removed everything that was poorly written rather than improved them, Wikipedia would have about 20 articles. Besides, other topics like Zeno's paradoxes have entire articles dedicated to the various proposed solutions, so the "we already have a solution" argument doesn't seem valid here. Android 93 (talk) 06:14, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- As you will see I have made a similar suggestion here but any proposals for change get a very frosty reception. Have a look at the history of this page and you will see that an IP editor recently added an extra explanatory section only to have it immediately deleted, with no explanation and with the deletion being marked as a minor edit!

- Another person tried to start a separate article only to find it set upon with a voracity I have never seen before in WP and deleted with days.

- I have been trying hard to work with the existing/historical editors to find way to improve the page without compromising the integrity of the current article. So far my advice has been that I can make minor edits but if they are reverted I must immediately discuss them.

- I Strongly believe that the current article fails to be convincing in respect of the basic paradox and that this must be improved. My view is supported by the fact that since the RFC there have been two people on the talk page who did not believe the article. One was eventually convinced by discussions here. As you say, there are other articles which make a better job of explaining their central paradoxes.Martin Hogbin (talk) 10:09, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- In an effort to allow this RFC to proceed unimpeded by "current editors" I have refrained from commenting, however I feel compelled to respond to this. I can see how editors new to this page might interpret responses to suggested changes as frosty, but in defense of the current editors this article is a featured article that has been through two featured article reviews [1] [2]. This certainly doesn't mean it's perfect, but it does mean there's been a significant amount of effort by multiple people spent on making the article not only mathematically correct with all major claims referenced to reliable sources but also comply with all other featured article criteria which include adherence to the WP:manual of style and a "professional standard" of writing. The recent addition by user:Technicalmayhem (a new, but not an IP, editor) was first deleted (by me) with this edit summary: revert - many WP:MOS issues with this addition. Technicalmayhem re-added it and this repeat addition was reverted by another editor also apparently watching the page. The re-addition was done with no explanation and marked as a minor edit (!), as well as the re-deletion. The separate article, "Introduction to the Monty Hall Problem", was created by user:Pello-500 (arguably the same user as 82.39.51.194 and 92.41.46.220) for the apparent purpose of including this user's preferred "solution" without gaining consensus to include it here. This is not how content disputes should be handled per Wikipedia:Dispute resolution, and since this user previously initiated this RFC he or she is clearly aware of the proper steps for handling content disputes but for whatever reason chose to ignore them. It's hard to interpret creating this article as anything other than bad faith tendentious editing.

- Rick, I was not referring to your reversion but this one: 4 September 2008 Jonobennett m (48,223 bytes) (Reverted 1 edit by 68.2.55.158.)Martin Hogbin (talk) 20:24, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- From my point of view, the discussion below of Martin Hogbin's suggestions for improvement has been proceeding pretty much exactly how such discussions should go. I'm not, and I don't think anyone else is, saying no changes can be made. The caution about making a change once and if it's reverted then discussing it was not intended to inhibit changes but to encourage them (per WP:BOLD). I partially agree with the point that the article fails to be convincing (not just one, but both "doubters" have apparently been convinced) however I'm highly skeptical that ANY explanation or even combination of explanations would convince all readers. To be clear, I'm not saying it can't be made more convincing but like it says in the lead - even when given a completely unambiguous statement of the Monty Hall problem, explanations, simulations, and formal mathematical proofs, many people still meet the correct answer with disbelief. -- Rick Block (talk) 18:09, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- I agree it will not be easy but surely it is worth a go. As with similar problems, explanations from many different angles could be a good place to start. What is the best way to proceed? I do not want to start editing the current article by adding a new section, which will start off badly written, formatted, and referenced and may well get removed. Do you agree that a development version of the article might be a good place to start, with the intention of a merger when agreed, or perhaps leave it as a separate article with a link from this one? Martin Hogbin (talk) 20:24, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- Creating a new article to be merged later is definitely not the way to proceed. Proposing the text for a change, or even a new section, here (well, probably not here but in a section below) on the talk page would be perfectly reasonable. If you're talking about major structural changes, you could create a sandbox version, perhaps on a page in your user space like user:Martin Hogbin/Monty Hall problem (draft). -- Rick Block (talk) 20:54, 6 September 2008 (UTC)

- I have set up a user page as described - see section below.Martin Hogbin (talk) 10:14, 7 September 2008 (UTC)

- keep original. If I understand correctly the two solutions that are being offered (no one has bothered to supply diffs), then I think the current (original) version is better. having taught this problem in the past, however, I think it needs some revisions. does anyone object if I do some editing? --Ludwigs2 03:07, 7 September 2008 (UTC)

Bayes was right, but I think the logic of the existing solution is flawed

The Bayesian analysis is correct to the extent that it demonstrates that the probability of the car being behind Door 1 remains 1/3 after the decisions are made by the player and the host. That is the "decisions" by the player and the host do not affect the probability of the car being behind Door 1.

However, I believe the interpretation of the Bayesian analysis is flawed.

In particular, although the Bayesian analysis correctly accounts for the fact that the host knows the location of the car it does not reflect knowledge gained by the player when it is revealed that the car is not behind Door 3.

Bayes's Theorem can be used to take account of the fact that the player learns the car is not behind door 3 by calculating the probability of the car being behind Door 1 given that it is not behind Door 3.

Let's do it in English.

The probability that the car is not behind Door 1 given that the car is not behind Door 3

= [(The probability that the car is not behind Door 3 given it is behind Door 1) x (The probability that the car is behind Door 1)] / (The probability that the car is not behind Door 3)

= [1 x 1/3] / 2/3

= 1/2

This result is consistent with many people's intuition that if there are two doors and a car is behind one of them then there is a 50:50 chance of the car being behind either door.

That is, I think conclusions shown on the website are wrong.

Given the debate that has already taken place I guess there will be some opposition to my view. --Paul Gerrard at APT (talk) 11:51, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

Paul, I would be happy to try and persuade you that you are wrong but this is not the place. You can email me at martin003@hogbin.org. Martin Hogbin (talk) 14:02, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- The basic issue is that "the probability that the car is not behind Door 1 given that it is not behind Door 3" (which is indeed 1/2) is NOT the question posed by the Monty Hall problem. In English, what we're looking for (flipping "is not behind Door 1" to "is behind Door 1" - seems a little clearer this way) is "the probability that the car is behind Door 1 given that the host opens Door 3". With the standard rules, this probability ("host opens Door 3") is 1/2 given the car is behind Door 1 (from the problem statement: If both remaining doors have goats behind them, he chooses one randomly). This probability is also 1/2 given the car is not behind Door 1, since if the car is not behind Door 1 it's equally likely to be behind Door 2 or Door 3. Combined, what this means is the probability the host opens Door 3 is 1/2 whether or not we're also given the car is behind Door 1. This makes the Bayes expansion be (1/2) x (1/3) / (1/2), i.e. 1/3. -- Rick Block (talk) 16:28, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- Looks like it is OK to answer here. Here is a very simple way to see that the probability of getting the car if you switch is 2/3. If you switch, you always get the opposite of what you started with. You have a 2/3 probability of starting with a goat. Martin Hogbin (talk) 16:51, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- This is simple, but it relies on an assumption that when the host opens a door nothing changes (or changes the question from "what is the probability of winning after the host opens a door given the Monty Hall rules" to "what is the probability of picking a car from among 3 doors"). Under the standard rules it turns out that the host opening a door doesn't affect the player's initial chances of having selected the car (this is reflected in the Bayes expansion above with the two 1/2's that cancel each other out), but this simple explanation does not use those rules so it is fundamentally incomplete (there is much more discussion of this in the #Suggestion to replace existing solution section thread just above). Why does this explanation not apply to Deal or No Deal? -- Rick Block (talk) 17:25, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- Yes Rick, you are quite right. However if I add to my explanation the observation that, with the standard rules, no information about the location of the car is given when the host opens a door and thus the original probability of getting a goat holds after the door has been opened, then my explanation is a good one for the standard rules case. However it is then not such a simple explanation and cannot be directly applied to other cases. At least I understand what the RFC is all about now. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:01, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- Here is rather extreme example to show what Rick means and why my original answer was incomplete. Suppose we work to the standard rules, so you would expect my explanation to apply, but, after he as opened a door, the host tells the contestant whether he has initially chosen a car or a goat (rather spoils the game) then the probability of getting a car if the contestant swaps is clearly not 2/3 but either 1 or 0 depending on what the host tells the contestant. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:12, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- The question still remains how we know given the standard rules that "no information about the location of the car is given when the host opens a door". This is an assertion, not reasoning, and (as it turns out) showing this with reasoning is not overly simple. Again, I think the best reference for this is the Morgan et al. paper (in the references), or the current version of this article. This topic was discussed at length several months ago, shortly before the latest featured article review - starting with Talk:Monty Hall problem/Archive 6#Rigorous solution. In my opinion the ensuing discussion (that continues in the archives into Talk:Monty Hall problem/Archive 7), somewhat contentiously spearheaded by an anonymous user (using multiple IP addresses in the range of user:70.137.168.95) who originally pointed us to the Morgan et al. paper, in conjunction with scrupulous referencing improvements to satisfy concerns raised during the last FARC have led to significant improvements in this article (as well as to my personal understanding of the subtleties involved in this problem). One of the key points this user brought to the discussion (backed up by the Morgan et al. paper) was that most solutions presented to the problem are overly simplified and include but don't justify the assertion that the host opening a door doesn't change the initial 1/3 probability. Another very good reference about this is the Falk paper (also in the references). According to Falk the answer that most people present (after the host opens a door, it's a 50/50 chance) is rooted in a deeply intuitive "equal probability" assumption; however many "correct" answers commonly presented simply replace this intuition with an appeal to another one, i.e. the "belief that exposing information that is already known does not affect probabilities". Neither of these is based on particularly sound reasoning and problems can be constructed where either one leads to an incorrect answer. This problem is contentious at least in part because it's not simple. -- Rick Block (talk) 21:21, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- This is simple, but it relies on an assumption that when the host opens a door nothing changes (or changes the question from "what is the probability of winning after the host opens a door given the Monty Hall rules" to "what is the probability of picking a car from among 3 doors"). Under the standard rules it turns out that the host opening a door doesn't affect the player's initial chances of having selected the car (this is reflected in the Bayes expansion above with the two 1/2's that cancel each other out), but this simple explanation does not use those rules so it is fundamentally incomplete (there is much more discussion of this in the #Suggestion to replace existing solution section thread just above). Why does this explanation not apply to Deal or No Deal? -- Rick Block (talk) 17:25, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- There certainly is more to this than meets the eye. Might a way forward be as follows? Formulate a version of the problem where a simple analysis, such as I gave, is correct. We are at this stage picking a problem to suit our desired answer. In other words construct a problem where what has been called the most attractive false solution is actually a good solution. Now clearly state our reformulated problem as an idealised version of the Monty Hall problem and give the, now correct, simple solution. My guess is that this will be what 90% of readers will want and expect. It is just a continuation of the process started by Krauss and Wang.

- The discussion about the hosts behaviour and the contestants understanding of this then can become a secondary, much more complicated, and perhaps contentious, discussion for those interested in the fine details.Martin Hogbin (talk) 22:25, 30 August 2008 (UTC)

- This has been suggested before - the problem is that if we do this we drift into WP:OR unless the version of the problem we present clearly meets WP:RS. I think this boils down to whether the solution currently presented is accessible to a lay person. I think the answer is yes (but I am sufficiently "into" this problem that I realize my opinion on this is basically worthless). -- Rick Block (talk) 04:14, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

- Maybe we should consider the occasional exception (WP:IGNORE) here. The dividing line between OR and verifiable is rather vague anyway; not all third party references should carry equal weight and the process of assessing how authoritative any given reference is is a form of OR. With this particular problem we could probably find more references, from normally authoritative sources, that give the completely wrong answer than we could good ones. On the other hand experience with the problem has shown that our intuition is not to be trusted either. Regarding the RFC, I have continued above.Martin Hogbin (talk) 09:35, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

Hi Martin, thanks for the information.

I agree with much of what you say, but I disagree with the assertion that:

- "no information about the location of the car is given when the host opens a door".

It seems to me that when the host opens a door the player is given information about the location of the car. In particular, the host's action informs the player that the car is not behind Door 3 and that the car must therefore be behind either Door 1 or Door 2.

- Yes, you are right, I put it badly.Martin Hogbin (talk) 12:59, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

This information does not alter the fact that at the outset of the game there was a 1/3 chance that the car could have been behind any particular door.

- That is right but also the chance a car is behind the door that I initially chose remains at 1/3 if the host must open a goat door and, if given a choice, must chose randomly, and I know all this. This is generally agreed to be true in the above circumstances but my mistake was to take this as being self evident. If the host acts differently, then the above statement is often not true. If you agree that, after a door is opened, the chances of the car being behind your initial door is still 1/3 then my argument still holds. Martin Hogbin (talk) 12:59, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

- I can't see the logic of the probability remaining 1/3. If it were 1/3 and it is known that there was a goat behind Door 3 this would mean that the probability of the car being behind Door 2 had risen to 2/3. I know that is what the website says, but in my response to Glopk below I explain why I believe that probabilities can't be transferred as suggested on the website. Can you point me to any of the previous discussion about transferring probabilities? --Paul Gerrard at APT (talk) 12:23, 1 September 2008 (UTC)

- Let me try a slightly different version of the problem. The contestant picks a door. We agree that he has a 2/3 chance of picking a goat. We also know that if he switches he will get the opposite of his original choice. Suppose, therefore, that this person decides, before a door is opened, that he will switch. Do you agree that he then must have a 2/3 chance of getting a car? Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:08, 1 September 2008 (UTC)

- Hi Martin - I agree that at the outset there is a 2/3 chance of picking a goat, but I am not sure what you mean when you say that "if he switches he will get the opposite of his original choice". Also, if the player decides to switch why would the probability of picking a car increase to 2/3. If you extend the logic to switching a second time would you say that the probability of picking the car was 1 (i.e. a certainty). What would be the reason for suggesting that deciding to switch would increase the probability of picking the car? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Paul Gerrard at APT (talk • contribs) 00:11, 2 September 2008 (UTC)

- By "if he switches he will get the opposite of his original choice" I refer to the simple fact that , if the player initially chooses a goat and the switches he must get a car(because his original choice is one of the goats and the host has removed the other one from play leaving the car as the only other door) and if the player initially chooses a car and switches he must get a goat (because there is only one car and he has it). The above always applies, without exception, regardless of the strategy of the player or the host (we are here assuming that the game rules require the host to always open a goat door and offer a swap).

- Regarding a second swap, no of course, the probability does not rise to 1. The whole point of this problem is that after a door has been opened, the player has more information as to the whereabouts of the car, making the unchosen door more likely to have it. I have to say, and indeed am saying, that the current explanation is not as convincing as it should be. I am currently trying to improve it. Martin Hogbin (talk) 08:46, 2 September 2008 (UTC)

However, while the original probabilities remain unchanged the information that the car was not placed behind Door 3 effectively changes the game from a "3 door game" to a "2 door game".

The effect of knowing that the car is not behind Door 3 on the probability that the car is behind Door 1 can be demonstrated as I have done above using Bayes' Theorem.

Bayes Theorem can also be used to calculate the probability that the car is behind Door 2 given that it is not behind Door 3. (The answer is 1/2.)

Our different perspectives are as intriguing as the puzzle itself.

What am I missing? (I have tried to make sense of the references with the exception of Morgan et al which costs $14)--Paul Gerrard at APT (talk) 11:29, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

- No, because the opening of a door does give you extra information about the chances of the car being behind the other door. Martin Hogbin (talk) 12:59, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

- Paul, please re-read the "Bayesian Analysis" section. As others have already pointed out, the proposition of interest for the MHP is not "The car is behind door i, given that it is not behind door 3", for . Rather, the player is interested in the truth of "The car is behind door i, given that the host opens door 3 after the the player initially chooses door j", for , and where represents everything the player knows prior to making the first choice, including the host's behavior. The two propositions are obviously different, and therefore it is to be expected that they evaluate to different numbers. But only the latter one matters. Further, the evaluation of using the Bayes theorem shows the need to make explicit the assumptions concerning the host's behavior through the value of , the probability of the proposition "The host opens door 3 after the player chooses door j, given that the car is behind door k". All possible host's behaviors are specified by assigning values to this function of j and k. The Bayesian Analysis section in the article shows only one particular such function, the one consistent with the "standard" interpretation of the MHP, i.e. "The host shows a goat behind one of the two doors not chosen by the player. If two such doors are available, they are equally likely to be opened".The Glopk (talk) 16:46, 31 August 2008 (UTC)

Thanks The Glopk, it is good to be reminded that is not the same as . This a very important distinction and I agree that these expressions are very different and that there is no reason to believe they should be equal.

It is therefore important to reconsider the problem to make sure we are trying to answer the same question. My understanding of the problem is that we are trying to determine whether it is to the advantage of the player to switch after the host opens a door.

We also need to review how the expressions relate to the issue of whether it is to the advantage of the player to switch after the host opens a door.

The differences between the expressions are subtle.

My understanding is that = 1/3 shows that the rules the host follows to select a door do not alter the probabilities - they are still 1/3.

However, does not take into the fact that the host has revealed that there is a goat behind Door 3 even though the rules of the game require the host to choose a goat door.

It is really hard to find words which explain why this is a problem, but please consider . If you evaluate this expression in the same way that website evaluates you will find that:

= = 1/3

Similarly, you will find = 1/3 unless you change the probabilities to reflect the fact that it is known that a goat is behind Door 3.

However, if you change the probability of a goat being behind Door 3 to zero then you must also change the probabilities of the car being behind the other 2 doors such that their sum is 1. This raises the question of what would the new probabilities become. I see no alternative other than 50% chance for both Door 1 and Door 2.

Also, I know the existing website suggests that the host's showing of the goat behind Door 3 has the effect of "transferring" the 1/3 of probability to Door 2. The following example helps demonstrate why I believe such transfers do not occur. Imagine a similar game with 3 doors, two goats, and a car. The probabilities for each door are 1/3. Also the probability of the car being behind any pair of doors is 2/3 (e.g. the probability that the car is behind either Door 1 or Door 2 is 2/3). Now imagine that any goat door is opened - what then happens to the probability that the car is behind either of the other doors? If we assume that probabilities are transfered as per the website then for each of the remaining two doors the probability that the car is behind that door becomes 2/3 and the sum of these 2 probabilities is 4/3 whereas the sum of the probabilities must be 1. Thus, there is a problem in transferring probabilities.

Now let's consider . It reflects everything that is known by the player. The process by which the host chose Door 3 has given no more information to the player than that a goat was behind Door 3. Thus, = 1/2 seems to me to indicate that it is the true probability of the car being behind Door 1 and there is no advantage in switching.

Finally, lets consider what happens to if we adjust the probabilities to reflect the fact that we know the car is not behind door 3 as suggested above.

That is and .

If you do this you will find that:

That is, the Bayesian Theorem actually gives the same result as providing the probabilities used in the formula are adjusted to take account of the fact that a goat is behind Door 3.

Thus, it seems to me that there is no advantage in switching. --Paul Gerrard at APT (talk) 11:47, 1 September 2008 (UTC)

- is the probability that the car is behind door i given the host opens door 3 after the player initially selected door j (under the rules of the game). This is exactly the question we're interested in. The rules of the game ensure the host opens a goat door. You say this "does not take into the fact that the host has revealed that there is a goat behind Door 3" and admit that it "is really hard to find words which explain why this is a problem". That's good, because it is not a problem.

- evaluates to 2/3, not 1/3, since

- (if the car is behind Door 2 and the player picks Door 1 the host is forced to open Door 3)

- Similarly, is 0, not 1/3, since

- (if the car is behind Door 3 and the player picks Door 1 the host never opens Door 3)

- No "changing of probabilities" is required to get these to sum to 1. Before the host opens Door 3 the probabilities are 1/3, 1/3, 1/3. After the host opens Door 3 (under the rules of the game) the probabilities are 1/3, 2/3, 0. The effect (in this case, under these rules) is that Door 3's probability has been "transferred" to Door 2. This doesn't say anything like you can group any two arbitrary doors and probabilities transfer between them.

- Our differences of opinion seem to hinge around what probabilities we feed into the Bayesian formula.

- If it is correct to say that all probabilities are 1/3 then I agree with your calculations.

- If it is correct to adjust probabilities to 1/2, 1/2, 0 for Doors 1, 2, 3 respectively then I believe my calculations are correct.

- If it is correct to say that all probabilities are 1/3 then I agree with your calculations.

- I believe you are right if we are talking about probabilities prior to the door being opened and I am right if we are talking about probabilies after the host opens a door. As we are trying to take account the information available to the player at the time the player must decide to switch or not not to switch, we must use the information available to the player and at this time the player knows only that there is a goat behind Door 3. The rules of the game provide no more information than this. Thus I believe the probabilities must be 1/2, 1/2, 0 for Doors 1, 2, 3 respectively rather than 1/3 for each door.

- With respect to the grouping of doors I agree that one cannot group doors and probabilities transfer between them. My example was to prove that one cannot do it. However, it seems to me that your solution does exactly this. Isn't your solution efectively saying that:

- The probability of the car being behind Door 1, 2, or, 3 is 1/3 for each door.

- You then group the 2 doors that are not chosen by the player and say there is a 2/3 chance the care is behind one or other of those doors.