Shofar: Difference between revisions

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

See Arthur l. Finkle, [http://www.geocities.com/afinkle221 Shofar Sounders Reference Manual], LA: Torah Aura, 1993 |

See Arthur l. Finkle, [http://www.geocities.com/afinkle221 Shofar Sounders Reference Manual], LA: Torah Aura, 1993 |

||

Mitzvah: Hearing the Sounds |

|||

The Sages indicated that the mitzvah was to hear the sounds of the shofar. They go so far as to establish whether a person hears the actual sound or just the echo at the outside of the pit or cave; the bottom; and midway. The Shulchan Aruch sums up that if the hearer hears the reverberation, the mitzvah is not valid. However, if the hearer perceives the direct sounds, he fulfils the mitzvah. See Mishnah Berurah 587:1-3. You can extrapolate this ruling to hearing the shofar on the radio, the Internet, etc. as being invalid. |

|||

In addition, if one hears the blast but with no intention of fulfilling the mitzvah, then there is no mitzvah. However, there is a minority decision on this point. |

|||

If one blows with the intention that all who hear will perform the mitzvah, the mitzvah is valid. If someone passes by and does intend to hear the Shofar, he can perform he mitzvah because the community blower blows for everybody. If he stands still, it is presumed he intends to hear. MB 590:9 |

|||

What Are the Qualifications for Sounding the Shofar? |

|||

The Shulchan Aruch begins its exploration of fitness by citing excluding classes of people: |

|||

1.Whoever is not obligated to fulfill the mitzvah of sounding the shofar should not substitute his efforts for another whose duty it is to perform a mitzvah. For example, the Baal Tekiah sounds a shofar for a synagogue in Chelm cannot perform he same mitzvah when another in the town of Lodz can fulfill the mitzvah. |

|||

2.The mitzvah is not valid for a deaf mute (cannot hear), moron (lacks the capacity) and a child (lacks the adult status) |

|||

3.Women are exempt because the mitzvah is time bound |

|||

4.A hermaphrodite may make his shofar sounding serve for other hermaphrodites |

|||

5.Women should not be Baal Tekia’s because they would be substituting her efforts for another whose duty it is to perform a mitzvah. However, if a female Baal Tekiya has already intoned the shofar for other women, it is valid. However, women should not make a blessing. |

|||

6.Only a freeman (not even a slave who will become free in the next month) can be a Baal Tekiya. MB 590:1-5 |

|||

Being a Baal Tekiya (Shofar Sounder) is an honor. |

|||

"The one who blows the shofar on Rosh Hashanah . . . should likewise be learned in the Torah and shall be God-fearing; the best man available. Nevertheless, every Jew is eligible for any sacred office, providing he is acceptable to the congregation. If, however, he sees that his choice will cause disruption, he should withdraw his candidacy, even if the improper person will be chosen” See Shulchan Aruch 3:72. |

|||

Moreover, the Baal Tekiya shall abstain from anything that may cause ritual contamination for three days prior to Rosh Hashanah. See Shulchan Aruch 3:73 |

|||

A Baal Tekiya can sound the shofar for shut-ins and home-bound women who have had baby. |

|||

If a blind blower was dismissed, but the community did not find a blower as proficient, he should be appointed as community blower. The touchstone is proficiency not disability. See Radbaz |

|||

==Choice of animal== |

==Choice of animal== |

||

Revision as of 19:15, 26 July 2009

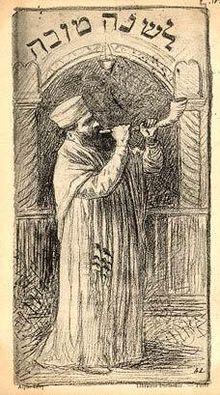

A shofar (Hebrew: שופר) is a horn used for Jewish religious purposes. Shofar-blowing is incorporated in synagogue services on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

In the Bible and rabbinic literature

The shofar is mentioned frequently in the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud and rabbinic literature. The blast of a shofar emanating from the thick cloud on Mount Sinai made the Israelites tremble in awe (Exodus 19, 20).

The shofar was used in to announce holidays (Ps. lxxxi. 4), and the Jubilee year (Lev. 25. 9). The first day of the seventh month (Tishri) is termed "a memorial of blowing" (Lev. 23. 24), or "a day of blowing" (Num. xxix. 1), the shofar. It was also employed in processions (II Sam. 6. 15; I Chron. 15. 28), as a musical accompaniment (Ps. 98. 6; comp. ib. xlvii. 5) and to signify the start of a war (Josh. 6. 4; Judges 3. 27; 7. 16, 20; I Sam. 8. 3). Note that the 'trumpets' described in Numbers 10 are a different instrument, described by the Hebrew word 'trumpet' not the word for shofar.

The Torah describes the first day of the seventh month (1st of Tishri = Rosh ha-Shanah) as a zikron teruah (memorial of blowing; Lev. xxiii) and as a yom teru'ah (day of blowing; Num. 29). This was interpreted by the Jewish sages as referring to the sounding the shofar.

In the Temple in Jerusalem, the shofar was sometimes used together with the trumpet. On New-Year's Day the principal ceremony was conducted with the shofar, which instrument was placed in the center with a trumpet on either side; it was the horn of a wild goat and straight in shape, being ornamented with gold at the mouthpiece. On fast-days the principal ceremony was conducted with the trumpets in the center and with a shofar on either side. On those occasions the shofarot were rams' horns curved in shape and ornamented with silver at the mouthpieces. On Yom Kippur of the jubilee year the ceremony was performed with the shofar as on New-Year's Day. Rosh Hoshana is the Jewish New Year. A ceremonial horn, called a “shofar” is blown, reminding Jews that God is king. A feast with symbolic food is eaten on Rosh Hashana, and the next ten days are spent in repentance. Rosh Hashana ends on Yom Kippur. Yom Kippur is a day of judgment, during which prayers are made asking for forgiveness.

The shofar was blown in the times of Joshua to help him capture Jericho. As they surrounded the walls, the shofar was blown and the Jews were able to capture the city. The shofar was commonly taken out to war so the troops would know when a battle would begin. The person who would blow the shofar would call out to the troops from atop a hill. All of the troops were able to hear the call of the shofar from their position because of its distinct noise.

Post-Biblical times

In post-Biblical times, the shofar was enhanced in its religious use because of the ban on playing musical instruments as a sign of mourning for the destruction of the temple. (It is noted that a full orchestra played in the temple, including, perhaps, a primitive organ.) The shofar continues to announce the New Year and the new moon, to introduce Shabbat, to carry out the commandment to sound it on Rosh Hashanah, and to mark the end of the day of fasting on Yom Kippur once the services have completed in the evening. The secular uses have been discarded (although the shofar was sounded to commemorate the reunification of Jerusalem in 1967) (Judith Kaplan Eisendrath, Heritage of Music, New York: UAHC, 1972, pp. 44-45).

The shofar is primarily associated with Rosh ha-Shanah. Indeed, Rosh Hashanah is called "Yom T’ruah" (the day of the shofar blast). In the Mishnah (book of early rabbinic laws derived from the Torah), a discussion centers on the centrality of the shofar in the time before the destruction of the second temple (70 AD). Indeed, the shofar was the center of the ceremony, with two silver trumpets playing a lesser role. On other solemn holidays, fasts, and new moon celebrations, two silver trumpets were featured, with one shofar playing a lesser role. The shofar is also associated with the jubilee year in which, every fifty years, Jewish law provided for the release of all slaves, land, and debts. The sound of the shofar on Rosh ha-Shanah announced the jubilee year, and the sound of the shofar on Yom Kippur proclaimed the actual release of financial encumbrances.

The halakha (Jewish law) rules that the shofar may not be sounded on Shabbat due to the potential that the ba’al tekiyah (shofar sounder) may inadvertently carry it which is in a class of forbidden Shabbat work (RH 29b) the historical explanation is that in ancient Israel, the shofar was sounded on Shabbat in the temple located in Jerusalem. After the temple’s destruction, the sounding of the shofar on Shabbat was restricted to the place where the great Sanhedrin (Jewish legislature and court from 400 BCE to 100 C.E.) was located. However, when the Sanhedrin ceased to exist, the sounding of the shofar on Shabbat was discontinued (Kieval, The High Holy Days, p. 114).

The shofar says, "Wake up from your (moral) sleep. You are asleep. Get up from your slumber. You are in a deep sleep. Search for your behavior. Become the best person you can. Remember God, the One Who created you." Mishneh Torah, Laws of Repentance 3:4.[1]

See Arthur l. Finkle, Shofar Sounders Reference Manual, LA: Torah Aura, 1993

Mitzvah: Hearing the Sounds

The Sages indicated that the mitzvah was to hear the sounds of the shofar. They go so far as to establish whether a person hears the actual sound or just the echo at the outside of the pit or cave; the bottom; and midway. The Shulchan Aruch sums up that if the hearer hears the reverberation, the mitzvah is not valid. However, if the hearer perceives the direct sounds, he fulfils the mitzvah. See Mishnah Berurah 587:1-3. You can extrapolate this ruling to hearing the shofar on the radio, the Internet, etc. as being invalid.

In addition, if one hears the blast but with no intention of fulfilling the mitzvah, then there is no mitzvah. However, there is a minority decision on this point.

If one blows with the intention that all who hear will perform the mitzvah, the mitzvah is valid. If someone passes by and does intend to hear the Shofar, he can perform he mitzvah because the community blower blows for everybody. If he stands still, it is presumed he intends to hear. MB 590:9

What Are the Qualifications for Sounding the Shofar?

The Shulchan Aruch begins its exploration of fitness by citing excluding classes of people:

1.Whoever is not obligated to fulfill the mitzvah of sounding the shofar should not substitute his efforts for another whose duty it is to perform a mitzvah. For example, the Baal Tekiah sounds a shofar for a synagogue in Chelm cannot perform he same mitzvah when another in the town of Lodz can fulfill the mitzvah. 2.The mitzvah is not valid for a deaf mute (cannot hear), moron (lacks the capacity) and a child (lacks the adult status) 3.Women are exempt because the mitzvah is time bound 4.A hermaphrodite may make his shofar sounding serve for other hermaphrodites 5.Women should not be Baal Tekia’s because they would be substituting her efforts for another whose duty it is to perform a mitzvah. However, if a female Baal Tekiya has already intoned the shofar for other women, it is valid. However, women should not make a blessing. 6.Only a freeman (not even a slave who will become free in the next month) can be a Baal Tekiya. MB 590:1-5 Being a Baal Tekiya (Shofar Sounder) is an honor.

"The one who blows the shofar on Rosh Hashanah . . . should likewise be learned in the Torah and shall be God-fearing; the best man available. Nevertheless, every Jew is eligible for any sacred office, providing he is acceptable to the congregation. If, however, he sees that his choice will cause disruption, he should withdraw his candidacy, even if the improper person will be chosen” See Shulchan Aruch 3:72.

Moreover, the Baal Tekiya shall abstain from anything that may cause ritual contamination for three days prior to Rosh Hashanah. See Shulchan Aruch 3:73

A Baal Tekiya can sound the shofar for shut-ins and home-bound women who have had baby.

If a blind blower was dismissed, but the community did not find a blower as proficient, he should be appointed as community blower. The touchstone is proficiency not disability. See Radbaz

Choice of animal

According to the Talmud, a shofar may be made from the horn of any animal except that of a cow or calf (Rosh Hashanah, 26a), although a ram is preferable. (Mishnah Berurah 586:1). There is no requirement for ritual slaughter (shechitah), and theoretically, the horn can come from a non-kosher animal based on the principle of mutar beficha (the material is acceptable for putting in the mouth). Moreover, since the mitzvah is hearing the shofar, not eating it, using the horn of a neveylah or a non-kosher animal falls into the category of tashmishe mitzvah (MB 586:16 (8) Since unkosher substances unfit for human consumption are not food (Avot 67b), it is permissible to use animal hair, anointing oil and incense produced from animal secretions and dyes of crimson, which are made from mollusks (Megillah 26b).

To cap this issue, a recent article appeared in the Journal of Halacha, Number LIII, and Contemporary Society, Rabbi Ari Z, Zivotofsky, Yemenite Shofar: Ideal for the Mitzvah?, Cleveland, OH: Rabbi Jacob Joseph School R. Ari Z, Zivotofsky, 2007

The Elef Hamagan (586:5) delineates the order of preference: 1) curved ram; 2) curved other sheep; 3) curved other animal; 4) straight - ram or otherwise; 5) non-kosher animal; 6) cow. The first four categories are used with a bracha, the fifth without a bracha, and the last, not at all. [2]

Shape and material

A shofar may be created from the horn of any kosher male animal from the Bovidae family except for cattle, which is specifically excluded. In practice two species are generally used: the Ashkenazi shofar is a domestic ram (see sheep), while the Sefardi shofar is a kudu.

Bovidae horns are made of keratin (the same material as human toenails and fingernails). An antler, on the other hand, is not a horn but solid bone. Antlers cannot be used as a shofar because they cannot be hollowed out.

A crack or hole in the shofar affecting the sound renders it unfit for ceremonial use. A shofar may not be painted in colors, but it may be carved with artistic designs (Shulkhan Arukh, Orach Chayim, 586, 17). Shofars (especially the Sephardi shofars) are often plated with silver across part of their length for display purposes, although this invalidates them for use in religious practices. According to Jewish law women and minors are exempt from the commandment of hearing the shofar blown (as is the case with any positive, time-bound commandment), but they are encouraged to attend the ceremony.

The horn is flattened and shaped by the application of heat, which softens it. A hole is made from the tip of the horn to the natural hollow inside. It is played much like a European brass instrument, with the player blowing through the hole, causing the air column inside to vibrate. Sephardi shofars usually have a carved mouthpiece resembling that of a European trumpet or French horn, but smaller. Ashkenazi shofars do not.

Because the hollow of the shofar is irregular in shape, the harmonics obtained when playing the instrument can vary: rather than a pure perfect fifth, intervals as narrow as a fourth, or as wide as a sixth may be produced.

The sounds

The tekiah and teruah sounds mentioned in the Bible were respectively bass and treble. The tekiah was a plain deep sound ending abruptly; the teruah, a trill between two tekiahs. These three sounds, constituting a bar of music, were rendered three times: first in honor of God's Kingship; next to recall the near sacrifice of Isaac, in order to cause the congregation to be remembered before God; and a third time to comply with the precept regarding the shofar.

Ten appropriate verses from the Bible are recited at each repetition, which ends with a benediction. Over time doubts arose as to the correct sound of the teruah. The Talmud is uncertain whether it means a moaning/groaning or a staccato beat sound. Shevarim was supposed to be composed of three connected short sounds; the teruah of nine very short notes divided into three disconnected or broken sequences of three notes each. The duration of the teruah is equal to that of the shevarim; and the tekiah is half the length of either. This doubt as to the nature of the real teruah, whether it was simply a moan, a staccato or both, necessitated two near-repetitions to make sure of securing the correct sound.

The sequence of the shofar blowing is thus tekiah, shevarim-teruah, tekiah; tekiah, shevarim, tekiah; tekiah, teruah, and then a final blast of "tekiah gadola" which means "big tekiah," held as long as possible. This formula makes thirty sounds for the series, with tekiah being one note, shevarium three, and teruah nine. This series of thirty sounds is repeated twice more, making ninety sounds in all. The trebling of the series is based on the mention of teruah three times in connection with the seventh month (Lev. xxiii, xxv; Num. xxix), and also on the above-mentioned division of the service into malchiyot, zichronot, and shofarot. In addition to these three repetitions, a single formula of ten sounds is rendered at the close of the service, making a total of 100 sounds. According to the Sephardic tradition, a full 101 blasts are sounded, corresponding to the 100 cries of the mother of Sisera, the captain of Jabin's army who did not make it home after being assassinated by the biblical Yael (Judges 5:28). One cry is left to symbolize the legitimate love of a mother mourning her son.

The performer

The expert who blows (or "blasts" or "sounds") the shofar is termed the Tokea (lit. "Blaster") or Ba'al Tekia (lit. "Master of the Blast"). Every Jew is eligible for this sacred office, providing he is acceptable to the congregation. If a potential choice will cause dissension, he should withdraw his candidacy, even if the improper person is chosen. See Shulkhan Arukh 3:72; The Ba'al Tekia shall abstain from anything that may cause ritual contamination for three days prior to Rosh ha-Shanah. See Shulkhan Arukh 3:73.

Shofar in National Liberation

During the Ottoman and the British occupation of Jerusalem, Jews were not allowed to sound the shofar at the Western Wall. After the Six Day War, Rabbi Shlomo Goren famously approached the Wall and sounded the shofar. An additional stanza was added to Naomi Shemer's song Yerushalayim Shel Zahav (Jerusalem of Gold) in which she sings, "שופר קורא בהר הבית בעיר העתיקה", "a shofar calls out from the Temple Mount in The Old City".

Shofar in Non-Rabbinic Judaism?

The Torah does not speak of a Rosh Hashanah, and if it had it would be the first day of the month of Nissan. The Torah specifies the first day of the Seventh month as Yom Teruah (Day of the Sounding), or Zichron Teruah (Remembering the Sounding). But the meaning of this term is unclear, because the word Teruah could mean a kind of trumpet (or Shofar) blast, but it could also mean a shout of rejoicing, not necessarily the blowing of a particular instrument. The only description of a celebration of the first day of the seventh month in the Bible is the one in Nehemiah 8:1-12 and there the blowing the Shofar is not mentioned. From the Book of Numbers and the Psalms we learn that the trumpet or Shofar were blown on Rosh-Chodesh, on the first showing of the new moon, which was the beginning of the Jewish month, In Rabbinic literature, the Mishnah discusses blowing the Shofar in the Herodean Temple and in peripheral synagogues on Rosh Hashanah. We do not know when this custom began, but it certainly became more significant as time went on and it acquired many symbols. (Best description of these appears in Isaac Arameh's treatise Akedat Yitzhak). The non-Rabbinic forms of Judaism accepted neither the idea of Rosh Hashanah nor the blowing of the Shofar. Samaritans

The Samaritans modeled themselves after the Jewish People. However, the Jewish People kept its distance from this polyglot ethnic group. Indeed, when Ezra, the Prophet returned to Jerusalem from his post a court advisor to the Persians (423 BCE), he forbade the Samaritans from building the Temple because they were not legitimately Jewish. The Talmud records that, after the Assyrians in 722 BCE conquered Northern Israel, the Assyrian authorities transplanted populations from their other conquered territories to Northern Israel and vice-versa. Accordingly, although many of these immigrants intermarried with the few Jews that were left, the religion became syncretized with several other pagan religions, always a nemesis of the Jewish faith community. The Samaritans, however, do not recognize Rabbinic Judaism, like the Karaites of the 8th century, In principle, the idea that the first day of the Seventh [biblical) month is Rosh Hashanah is an innovation of Rabbinic Judaism as well as the custom of blowing the Shofar on that day. The Samaritans celebrate the day by prayers and reading from the Torah. There is no Shofar blowing. For them it is also the beginning of preparation for Yom Kippur.

Karaites

The Karaites rejected the Rabbinic obligation of Shofar blowing. The most important authority on this is the great Karaite Hacham, Eliyahu Basheitzy of the fifteenth century. In his book Aderet Eliyahu (which is still considered the most important source of Karaite Halacha) he specifically denounced the Rabbinic ruling about Shofar blowing. According to Basheitzy, Teruah means noise of rejoicing which is executed by the human voice and not by any instrument.

Ethiopian Beita-Israel Tradition

It was not until 1844, when a missionary found a people observing Jewish ceremonies, going back to biblical injunctions that Ethiopian Jews were known to the Jewish world. Although there is many disputes about how this sect arose, the most common belief is that some Ethiopian people converted to Judaism when the Temple stood. However, after the destruction of the Temple, this sect was cut off form subsequent mainstream Jewry. Thus, Rabbinical Judaism was unknown to these Jews, most of whom lived in the poverty-stricken Gondar region in Northern Ethiopia. Most scholarship points to the conversion of these African people sometime before the destruction of the Second Temple. After the Romans sacked the Temple and dispersed the Jewish People form Jerusalem, communications apparently broke off from the Ethiopian Jewish community. Much of the religious tradition derives from the Hebrew Scripture, but not in Rabbinical sources. For example, during Passover, they sacrificed a sheep and the family feasted on it on the 14th day of Nissan. There is another school of thought that believes that the Beita -Israel tradition received much of its liturgy from Ethiopian Christian sources. When the first large group of Beita-Israel arrived in Israel, the Jewish Rabbinical courts insisted that all males be re-circumcised evidence that they were Jews, under the Rabbinical tradition. To this injunction, the Ethiopians objected. Nevertheless, they subsequently became involved in the Sephardic ritual community. As to the Ethiopian Beita-Israel tradition. The first day of the seventh month is called "berhan sharaqa" which means "the light appeared" (which is a commemoration of the birth of the world) and "tazkara Abraham", the commemoration of Abraham, relating to the binding of Isaac. About two generations ago they started calling it "re-esha awda amat," the head of the year. We do not know when they started to relate this day to the birth of the world or to the binding of Isaac. Their old customs do not testify to either. Thus for example their reading from the Orit ( the Ge'ez Bible) on this day does not include Genesis 1 or the story of the Akedah. It seems that the associations came from the influence of Jewish Rabbinic sources with which Beita-Israel came in contact from the late 19th century on. From some testimonies, we know that at one point they adopted the custom of blowing the ram's horn in commemoration of the binding of Isaac. But this custom fell soon into disuse and no Ethiopian community practiced it until it was re-introduced in Israel by the Rabbinic authorities of the State (See Kay Kaufman Shelemay, "Music, Ritual and Falasha History," (Michigan State University, 1986). [4]

Use in modern times

Religious Usage

The shofar is used mainly on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It is blown in synagogues to mark the end of the fast at Yom Kippur, and blown at four particular occasions in the prayers on Rosh Hashanah. Because of its inherent ties to the Days of Repentance and the inspiration that comes along with hearing its piercing blasts, the shofar is also blown after morning services for the entire month of Elul, the last month of the Jewish civil year and the sixth of the Jewish ecclesiastical year. It is not blown on the last day of month, however, to mark the difference between the voluntary blasts of the month and the mandatory blasts of the holiday. Shofar blasts are also used during penitential rituals such as Yom Kippur Katan and optional prayer services called during times of communal distress. The exact modes of sounding can vary from location to location.

Non-Religious Musical Usage

The shofar is sometimes used in Western classical music. Edward Elgar's oratorio The Apostles includes the sound of a shofar blowing, although other instruments, such as the flugelhorn, are usually used instead.

In pop music, the shofar is used by the Israeli Oriental metal band Salem in their adaptation of "Al Taster" psalm. The late trumpeter Lester Bowie played a shofar with the Art Ensemble of Chicago. In Joey Arkenstat's album Bane, the former bassist for Phish is credited for playing the shofar. In the musical "Godspell", the first act opens with cast member David Haskell blowing the shofar, in preparation for singing "Prepare Ye the Way of the Lord." In his performances, Israeli composer and singer Shlomo Gronich uses the shofar to produce a very wide range of notes. [5]

See also

References

- ^ http://www.divreinavon.com/pdf/Anticipation_Consummation.pdf The Shofar: Impetus to Anticipation & Consummation

- ^ Elef Hamagen, Rabbi Shemarya Hakreti, edited by Aharon Erand, Jerusalem: Mekitzei Nirdamim, 2003

- ^ JERUSALEM OF GOLD. accessed 9 Dec. 2008

- ^ http://www.geocities.com/afinkle221

- ^ The Abraham Fund Initiatives::Press Clips - Crossing the Middle Eastern Tightrope

Arthur L. Finkle, Easy Guide to Shofar Sounding, LA: Torah Aura, 2003

External links

- Hearing Shofar: The Still Small Voice of the Ram's Horn by Michael T. Chusid, a scholarly study of the shofar from a variety of perspectives.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)