Juan Manuel de Rosas: Difference between revisions

Cambalachero (talk | contribs) |

Cambalachero (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

During his years out of office (1832-1835), Rosas waged a military campaign against the indigenous population in southern Argentina. As [[Charles Darwin]] related in ''[[The Voyage of the Beagle]]'', he met Rosas in the early 1830s, who was then engaged in exterminating tribes of wandering horse-mounted [[Indigenous Peoples of the Americas|Indians]], describing him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and ''"obtained an unbounded popularity in the countryside, and in consequence a despotic power"''. Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. In his Palermo house, which in fact was Argentina's government house, in the evenings balls, he used buffoons to tell foreign Ambassadors harsh things which had to be taken as coming from buffoons; in fact he was sending them. |

During his years out of office (1832-1835), Rosas waged a military campaign against the indigenous population in southern Argentina. As [[Charles Darwin]] related in ''[[The Voyage of the Beagle]]'', he met Rosas in the early 1830s, who was then engaged in exterminating tribes of wandering horse-mounted [[Indigenous Peoples of the Americas|Indians]], describing him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and ''"obtained an unbounded popularity in the countryside, and in consequence a despotic power"''. Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. In his Palermo house, which in fact was Argentina's government house, in the evenings balls, he used buffoons to tell foreign Ambassadors harsh things which had to be taken as coming from buffoons; in fact he was sending them. |

||

In 1835, Rosas was offered "la suma del poder" which gave him total power with no oversight and his |

In 1835, Rosas was offered "la suma del poder" which gave him total power with no oversight and his absolutist regime began. |

||

To enforce |

To enforce his will there arose a secret organization known as the [[Mazorcas]], a militia that beat up or even murdered Rosas' opponents. |

||

As a leader, Rosas portrayed himself as a man of the people, who could relate to the working class of [[gaucho]]s and [[Afro-Argentines]]. Rosas used his ''man of the people'' ideal to unify [[Argentina]] during his era. Rosas also invited the [[Jesuits]] back into the country and because of this move they supported him whole-heartedly. Rosas supporters called themselves ''Rosistas''. Rosas also had his portrait be displayed in all churches and public places as a symbol of complete control. Rosas claimed to be a [[Federales (Argentina)|Federalist]] but really was a centralist and established unity through tyranny.<ref>Britannica</ref> Rosas' rule was filled with violence — he killed his opponents and anyone else who would not support him. |

As a leader, Rosas portrayed himself as a man of the people, who could relate to the working class of [[gaucho]]s and [[Afro-Argentines]]. Rosas used his ''man of the people'' ideal to unify [[Argentina]] during his era. Rosas also invited the [[Jesuits]] back into the country and because of this move they supported him whole-heartedly. Rosas supporters called themselves ''Rosistas''. Rosas also had his portrait be displayed in all churches and public places as a symbol of complete control. Rosas claimed to be a [[Federales (Argentina)|Federalist]] but really was a centralist and established unity through tyranny.<ref>Britannica</ref> Rosas' rule was filled with violence — he killed his opponents and anyone else who would not support him. |

||

Revision as of 02:13, 25 February 2010

Juan Manuel de Rosas | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17 Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office March 7 1835 – February 3 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Vicente Maza |

| Succeeded by | Vicente López y Planes |

| 13 Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office December 8 1829 – December 17 1832 | |

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio March 30 1793 Buenos Aires |

| Died | March 14 1877 Southampton |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Federal Party |

| Spouse | Encarnación Ezcurra |

Juan Manuel de Rosas (born Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio in Buenos Aires, March 30, 1793 – Southampton, Hampshire, March 14, 1877), was a conservative Argentine politician who governed the Buenos Aires Province from 1829 to 1832 and again, from 1835 to 1852. Rosas was one of the first famous caudillos in Ibero-America and through his rule united Argentina, provided an efficient government and strengthened the economy. The change in family name from Rozas to Rosas came because his mother told him he was stealing her cattle. Furious, he changed his family name. After that, he worked as an "arriero", carrying cattle through the immensities of the pampas.

He was the son of León Ortiz de Rosas y de la Cuadra and wife Agustina Teresa López de Osornio. Born to one of the wealthiest families in the River Plate region, Rosas ran away from home at a young age and began working in the fields while relatives offered him food and shelter. He married right before age 20 on March 16, 1813 to the almost 18-year-old María de la Encarnación de Ezcurra y Arguibel and they had one child, a daughter Manuela Robustiana de Rosas y Ezcurra, born in Buenos Aires on May 24, 1817. Rosas established a meat-salting plant when he was twenty-two and the business immediately flourished. It became so successful that ranchers were afraid Rosas' business would become more popular than their own and laws were passed to end his plant. [1]

Rosas bought a large amount of land and began living the typical rancher's life. Instead of fighting with the gauchos, he became one of them and earned their respect and trust. When civil war broke out in 1820, Rosas organized a regiment of gauchos and soon became a national figure through his efforts to restore peace and order.

After Lavalle's army murdered Manuel Dorrego, who was head of government in Buenos Aires, the position was open and in 1829 Rosas was elected as governor of Buenos Aires. He had a successful and popular first term but refused to run for a second term even though public support was strong.[1] In subsequent years, Rosas went in and out of power, but remained a strong leader.

During his years out of office (1832-1835), Rosas waged a military campaign against the indigenous population in southern Argentina. As Charles Darwin related in The Voyage of the Beagle, he met Rosas in the early 1830s, who was then engaged in exterminating tribes of wandering horse-mounted Indians, describing him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and "obtained an unbounded popularity in the countryside, and in consequence a despotic power". Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. In his Palermo house, which in fact was Argentina's government house, in the evenings balls, he used buffoons to tell foreign Ambassadors harsh things which had to be taken as coming from buffoons; in fact he was sending them.

In 1835, Rosas was offered "la suma del poder" which gave him total power with no oversight and his absolutist regime began.

To enforce his will there arose a secret organization known as the Mazorcas, a militia that beat up or even murdered Rosas' opponents.

As a leader, Rosas portrayed himself as a man of the people, who could relate to the working class of gauchos and Afro-Argentines. Rosas used his man of the people ideal to unify Argentina during his era. Rosas also invited the Jesuits back into the country and because of this move they supported him whole-heartedly. Rosas supporters called themselves Rosistas. Rosas also had his portrait be displayed in all churches and public places as a symbol of complete control. Rosas claimed to be a Federalist but really was a centralist and established unity through tyranny.[2] Rosas' rule was filled with violence — he killed his opponents and anyone else who would not support him.

His wife Encarnación died in Buenos Aires on October 20, 1838.

The people who opposed Rosas formed a group called Asociacion de Mayo-May Brotherhood. It was a literary group that became politically active and aimed at exposing Rosas' actions. Some of the literature against him includes The Slaughter House, Socialist Dogma, Amalia and Facundo. Meetings which had high attendance at first soon had few members attending out of fear of prosecution. Rosas' opponents during his rule were dissidents, such as José María Paz, Salvador M. del Carril, Juan Bautista Alberdi, Esteban Echeverria, Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.[1] Rosas political opponents were exiled to other countries, such as Uruguay and Chile.

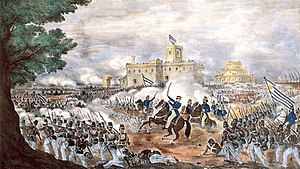

By the end of his reign, many of his supporters turned on him. General Urquiza, who was governor of the Entre Ríos Province and once backed Rosas, organized an army against him. Other provinces as well as Brazil and Uruguay joined the fight to take down the dictator.[1] On February 3, 1852, Rosas was overthrown when his army was defeated at the Battle of Caseros. After Caseros battle Rosas spent the rest of his life in exile, in the United Kingdom, as a farmer in Southampton. He was initially buried in the Southampton Old Cemetery in Southampton Common until his body was exhumed in 1989 and transferred to the La Recoleta Cemetery in Argentina.

Rosas received the 'combat sable' from General San Martin, 'maximum hero' of Argentina, who judged that Rosas was the only man capable of defending Argentina against the European powers, especially the British.

Critisism and historical perspective

The figure of Juan Manuel de Rosas and his government generated strong conflicting viewpoints, both in his own time and afterwards.

In the context of the Argentine Civil War, Rosas was the main leader of the Federalist party, and as such the most part of the controversies around him were motivated by the preexistent antagonism of Federalism with the Unitarian Party. During the government of Rosas most unitarians fled to neighbour countries, mostly to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil; among them we can find Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who wrote Facundo while living in Chile. Facundo is a critic biography of Facundo Quiroga, another federalist caudillo, but Sarmiento used it to pass many indirect or direct critics to Rosas himself. Some members of the 1837 generation, such as Esteban Echeverría or Juan Bautista Alberdi, tried to generate an alternative to the unitarians-federalists antagonism, but had to flee to other countries as well.

After the defeat of Rosas in Caseros and the return of his political adversaries, it was decided to portrait him under a negative light. The legislature of Buenos Aires declared him charged him with High treason in 1857, Nicolás Arbarellos supported his vote with the following speech:

We can't leave to History the trial of the tyrant Rosas. What will History say when they see that England has returned to that tyrant the cannons taken in war action and saluted his bloody flag and stained with a 21-gun salute? The France that has made common cause with the enemies of Rosas, who began the crusade where General Lavalle also appears, in time abandoned him and treated with Rosas, and also had to salute his flag with 21 guns. I ask, Lord, if these events wouldn't erase in history all we the enemies of Rosas can say, if not sanctioned by a legislative act as this law [...] What will be told in history, and this is sad to say, when it is known that the brave Admiral Brown, the hero of the Navy of the Independence, was the admiral who defended the tyranny of Rosas? That the General San Martin, the conqueror of the Andes, the father of the Argentine glories, made him the greatest tribute that can be given to a soldier by handing him his sword? Will this man, Rosas, be seen in 20 or 50 years, as we see him in 5 years after his fall, if we don't forego to vote a law that punishes him definitely with the taunt of being a traitor? No sir, we can not leave the trial of Rosas to history, because if we do not say from now he was a traitor, and taught in school to hate him, Rosas will not be considered by history as a tyrant, perhaps he would as the greatest and most glorious of Argentines.[3]

The first historians of Argentina, such as Bartolomé Mitre, were vocal critics of Rosas, and for many years there was a clear consensus in condemning him. Adolfo Saldías was the first in not condemning him entirely, and in the book "Historia de la Confederación Argentina" he supported his international policy, while keeping the usual rejection on the treatment given by Rosas to detractors. Authors like Levene, Molinari or Ravignani, in the 1930 decade, would develop a neutral approach to Rosas, that Ravignani defined as "Nor with Rosas, nor against Rosas".[4] Their work would be more oriented towards the positive things of the early years of Rosas, and less into the most polemic ones.[4]

Years later, a new historiographical flow made an active and strong support of Rosas and other caudillos. Because of its great differences with the early historians the local historiography knows them as revisionists, while the early one is named "official" or "academic" instead. However, despite namings, the early historiography of Argentina hasn't always followed standard academic procedures, nor developed hegemonic views at all topics.[5] They would expand the work of Saldías and Ernesto Quesada, and developed instead negative views about Mitre, Sarmiento, Rivadavia and the unitarians.

Modern historians like Felipe Pigna or Félix Luna avoid joining the dispute, describing instead the existence of conflicting viewpoints towards Rosas.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Crow

- ^ Britannica

- ^ O'Donnell, Pacho (2009). Juan Manuel de Rosas, el maldito de la historia oficial. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editorial Norma. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-987-545-555-9.

Spanish: No puede librarse a la Historia el fallo del tirano Rosas. ¿Qué dirá la Historia cuando se vea que la Inglaterra ha devuelto a ese tirano los cañones tomados en acción de guerra y saludado su pabellón sangriento y manchado con una salva de 21 cañonazos? La Francia que hizo causa común con los enemigos de Rosas, que inició la cruzada en la que figura el General Lavalle, a su tiempo le abandonó y trató con Rosas, y también debió saludar su pabellón con 21 cañonazos. Yo pregunto, Señor, si estos hechos no borrarán en la Historia todo cuanto podemos decir los enemigos de Rosas, si no lo sancionamos con un acto legislativo como esta ley [...] ¿Qué se dirá en la Historia, y esto es triste decirlo, cuando se sepa que el valiente Almirante Brown, el héroe de la marina de guerra de la Independencia, fue el Almirante que defendió la tiranía de Rosas? ¿Que el general San Martín, el vencedor de los Andes, el padre de las glorias argentinas, le hizo el homenaje más grandioso que pueda hacerse a un militar entregándole su espada? ¿Se verá este hombre, Rosas, dentro de 20 o 50 años, tal como lo vemos nosotros a 5 años de su caída, si no nos adelantamos a votar una ley que lo castigue definitivamente con el dicterio de traidor? No señor, no podemos dejar el juicio de Rosas a la Historia, porque si no decimos desde ahora que era un traidor, y enseñamos en la escuela a odiarlo, Rosas no será considerado por la Historia como un tirano, quizá lo sería como el más grande y glorioso de los argentinos.

- ^ a b Devoto, Fernando (2009). Historia de la Historiografía Argentina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. p. 181. ISBN 978-950-07-3076-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Devoto, Fernando (2009). Historia de la Historiografía Argentina. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. p. 202. ISBN 978-950-07-3076-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Argentine Caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas, by John Lynch (1981, 2001).

- Crow, John A. The Epic of Latin America. New York: University of California P, 1992.

- "Juan Manuel de Rosas." Britannica. 2008. 25 Oct. 2008.