Florence Nightingale: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with 'HI :)' |

m Reverted edits by 194.81.239.15 (talk) to last revision by Auranor (HG) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Medical Person |

|||

HI :) |

|||

|name = Florence Nightingale |

|||

|image = Florence Nightingale CDV by H Lenthall.jpg |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date|1820|5|12|df=y}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Florence]], [[Grand Duchy of Tuscany]] |

|||

|death_date = {{death date and age|1910|8|13|1820|5|12|df=y}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Park Lane (road)|Park Lane]], London, United Kingdom |

|||

|profession = [[Nurse]] and [[Statistician]] |

|||

|specialism = Hospital [[hygiene]] and [[sanitation]] |

|||

|research_field = |

|||

|known_for = Pioneering modern nursing |

|||

|education = |

|||

|work_institutions = [[Selimiye Barracks]], [[Üsküdar|Scutari]] |

|||

|awards = [[Royal Red Cross]] (1883) <br />[[Order of Merit (Commonwealth)|Order of Merit]] (1907) |

|||

|signature = Florence Nightingale Signature.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Florence Nightingale''', [[Order of Merit (Commonwealth)|OM]], [[Royal Red Cross|RRC]] ({{pron-en|ˈflɒrəns ˈnaɪtɨŋɡeɪl}}, historically {{IPA-endia|ˈflɒɾəns|}}; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was a celebrated [[English people|English]] [[nurse]], writer and [[statistician]]. A [[Universal reconciliation|Christian universalist]], Nightingale believed that God had called her to be a nurse. She came to prominence for her pioneering work in [[nursing]] during the [[Crimean War]], where she tended to wounded soldiers. She was dubbed "The Lady with the Lamp" after her habit of making rounds at night. |

|||

Nightingale laid the foundation of professional nursing with the establishment, in 1860, of her nursing school at [[St Thomas' Hospital]] in [[London]], the first secular nursing school in the world. The [[Nightingale Pledge]] taken by new nurses was named in her honour, and the annual [[International Nurses Day]] is celebrated around the world on her birthday. |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

===Early life=== |

|||

[[Image:Embley Park.jpg|thumb|[[Embley Park]], now a school, was one of the family homes of William Nightingale]] |

|||

Florence Nightingale was born into a rich, upper-class, well-connected British family at the [[Villa Colombaia]],<ref>''[http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/house.htm Florence Nightingale's birthplace]'' with photo of commemorative plaque</ref> near the [[Porta Romana]] at Bellosguardo in Florence, Italy, and was named after the city of her birth. Florence's older sister [[Frances Parthenope Verney|Frances Parthenope]] ({{pron-en|pɑrˈθiːnəpɪ}}) had similarly been named after her place of birth, ''Parthenopolis'', a [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] settlement now part of the city of [[Naples]]. |

|||

Her parents were [[William Nightingale|William Edward Nightingale, born William Edward Shore]] (1794–1874) and Frances ("Fanny") Nightingale ''née'' Smith (1789–1880). William's mother Mary ''née'' Evans was the niece of one Peter Nightingale, under the terms of whose will William inherited his estate [[Dethick, Lea and Holloway|Lea Hurst]] in [[Derbyshire]], and assumed the name and arms of Nightingale. Fanny's father (Florence's maternal grandfather) was the abolitionist [[William Smith (abolitionist)|William Smith]]. (For family trees, see <ref>http://www.rotherhamweb.co.uk/genealogy/shore.htm</ref>) |

|||

Inspired by what she took as a call from God in February 1837 while at [[Embley Park]], Florence announced her decision to enter nursing in 1844, despite the intense anger and distress of her mother and sister. In this, she rebelled against the expected role for a woman of her status, which was to become a wife and mother. Nightingale worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in spite of opposition from her family and the restrictive societal code for affluent young English women. |

|||

[[File:Florence Nightingale by Goodman, 1858.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Florence Nightingale, circa 1858]] |

|||

Nightingale was courted by politician and poet [[Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton]], but she rejected him, convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing. |

|||

In Rome in 1847, she met [[Sidney Herbert, 1st Baron Herbert of Lea|Sidney Herbert]], a brilliant politician who had been [[Secretary at War]] (1845–1846), a position he would hold again during the [[Crimean War]]. Herbert was on his honeymoon; he and Nightingale became lifelong close friends. Herbert and his wife were instrumental in facilitating Nightingale's nursing work in the Crimea, and she became a key adviser to him in his political career, though she was accused by some of having hastened Herbert's death from [[Bright's Disease]] in 1861 because of the pressure her programme of reform placed on him. |

|||

Nightingale also much later had strong relations with [[Benjamin Jowett]], who may have wanted to marry her. |

|||

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and Selina Bracebridge) as far as Greece and Egypt. Her writings on Egypt in particular are testimony to her learning, literary skill and philosophy of life. Sailing up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel in January 1850, she wrote<blockquote>"I don't think I ever saw anything which affected me much more than this." And, considering the temple: "Sublime in the highest style of intellectual beauty, intellect without effort, without suffering... not a feature is correct – but the whole effect is more expressive of spiritual grandeur than anything I could have imagined. It makes the impression upon one that thousands of voices do, uniting in one unanimous simultaneous feeling of enthusiasm or emotion, which is said to overcome the strongest man."</blockquote> At Thebes she wrote of being "called to God" while a week later near Cairo she wrote in her diary (as distinct from her far longer letters that her elder sister Parthenope was to print after her return): "God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation."<ref>Edward Chaney, "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution", in: ''Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines'', eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York, 2006), 39-74.</ref> Later in 1850, she visited the Lutheran religious community at [[Düsseldorf-Kaiserswerth|Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein]] where she observed Pastor [[Theodor Fliedner]] and the deaconesses working for the sick and the deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life, and issued her findings anonymously in 1851; ''The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses, etc.'' was her first published work.<ref>Oxford Dictionary of National Biography</ref> |

|||

On 22 August 1853, Nightingale took the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, London, a position she held until October 1854.<ref name=hsguide>''[http://www.harleystreetguide.co.uk/about/history/ History of Harley Street]'' at Harley Street Guide (commercial website)</ref> Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly £25,000/US$50,000 in present terms), which allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career. |

|||

===Crimean War=== |

|||

[[File:Balaklava sick 2.jpg|thumb|A tinted [[lithograph]] by [[William Simpson (artist)|William Simpson]] illustrating conditions of the sick and injured in [[Balaklava]]]] |

|||

[[File:Hospital at Scutari 2a.jpg|thumb|A ward of the hospital at [[Üsküdar|Scutari]] where Nightingale worked, from an 1856 lithograph]] |

|||

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the [[Crimean War]], which became her central focus when reports began to filter back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded. On 21 October 1854, she and a staff of 38 women volunteer nurses, trained by Nightingale and including her aunt Mai Smith,<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Gill |

|||

| first = Christopher J. |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = Gillian C. Gill |

|||

| title =Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined |

|||

| journal =Clinical Infectious Diseases |

|||

| volume =40 |

|||

| issue =12 |

|||

| pages =1799–1805 |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| location = |

|||

|year=2005 |

|||

| url =http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/430380 |

|||

| doi =10.1086/430380 |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate =2007-10-07 |

|||

| pmid = 15909269 |

|||

| month = Jun |

|||

| last1 = Gill |

|||

| first1 = CJ |

|||

| last2 = Gill |

|||

| first2 = GC |

|||

| issn = 1058-4838 |

|||

}}</ref> were sent (under the authorisation of Sidney Herbert) to [[Ottoman Empire]], about {{convert|295|nmi|km mi|lk=in}} across the [[Black Sea]] from [[Balaklava]] in the [[Crimea]], where the main British camp was based. |

|||

Nightingale arrived early in November 1854 at [[Selimiye Barracks]] in Scutari (modern-day [[Üsküdar]] in [[Istanbul]]). She and her nurses found wounded soldiers being badly cared for by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. [[Medicine]]s were in short supply, [[hygiene]] was being neglected, and mass [[infection]]s were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients. |

|||

Until recently it was commonly asserted that Nightingale reduced the death rate from 42% to 2% either by making improvements in hygiene herself or by calling for the Sanitary Commission. For example the 1911 first edition of the Dictionary of National Biography made this claim, but the second edition in 2001 did not. However, death rates did not drop; on the contrary, they began to rise. The death count was the highest of all hospitals in the region. During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as [[typhus]], [[typhoid]], [[cholera]] and [[dysentery]] than from battle wounds. Conditions at the temporary barracks hospital were so fatal to the patients because of overcrowding and the hospital's defective [[sanitary sewer|sewer]]s and lack of ventilation. A Sanitary Commission had to be sent out by the British government to Scutari in March 1855, almost six months after Florence Nightingale had arrived, and effected flushing out the sewers and improvements to ventilation.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=dRpgFsQ7nqkC&pg=PA114&lpg=PA114&dq=sanitary+commissioner+Scutari |title=Florence Nightingale: Measuring Hospital Care Outcomes |publisher=Books.google.com |date= 1999-08|accessdate=2010-03-13|isbn=0866885595|author1=Nightingale, Florence}}</ref> Death rates were sharply reduced. During the war she did not recognise hygiene as the predominant cause of death, and she never claimed credit for helping to reduce the death rate.<ref name="Florence Nightingale 1998">''Florence Nightingale, Avenging Angel'' by Hugh Small (Constable 1998)</ref> |

|||

Nightingale continued believing the death rates were due to poor nutrition and supplies and overworking of the soldiers.<!-- not consistent with her belief in Miasma theory of disease stated earlier ??? check --> It was not until after she returned to Britain and began collecting evidence before the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army that she came to believe that most of the soldiers at the hospital were killed by poor living conditions. This experience influenced her later career, when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. Consequently, she reduced deaths in the army during peacetime and turned attention to the sanitary design of hospitals. |

|||

====The Lady with the Lamp==== |

|||

During the Crimean campaign, Florence Nightingale gained the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp", deriving from a phrase in a report in ''The Times'': |

|||

<blockquote>She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.<ref>Cited in Cook, E. T. ''The Life of Florence Nightingale.'' (1913) Vol 1, p 237.</ref> </blockquote> |

|||

[[File:Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari by Jerry Barrett.jpg|thumb|"Nightingale receiving the Wounded at Scutari", a portrait by [[Jerry Barrett]]]] |

|||

The phrase was further popularised by [[Henry Wadsworth Longfellow]]'s 1857 poem "Santa Filomena":<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theatlantic.com/unbound/poetry/nov1857/filomena.htm |title=''The Atlantic Monthly''; November 1857; "Santa Filomena," by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow ; Volume 1, No. 1; pages 22-23 |publisher=Theatlantic.com |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>Lo! in that house of misery<br /> |

|||

A lady with a lamp I see<br /> |

|||

Pass through the glimmering gloom,<br /> |

|||

And flit from room to room.</blockquote> |

|||

===Later career=== |

|||

While she was in the Crimea, on 29 November 1855, a public meeting to give recognition to Florence Nightingale for her work in the war led to the establishment of the Nightingale Fund for the training of nurses. There was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as honorary secretary of the fund, and the [[Prince George, Duke of Cambridge|Duke of Cambridge]] was chairman. Nightingale was considered a pioneer in the concept of ''[[medical tourism]]'' as well, on the basis of her letters from 1856 in which she wrote of spas in Ottoman Empire, detailing the health conditions, physical descriptions, dietary information, and other vitally important details of patients whom she directed there (where treatment was significantly less expensive than in Switzerland). It may be assumed {{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} she was directing patients of meagre means to affordable treatment. |

|||

By 1859 Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the Nightingale Training School at [[St. Thomas' Hospital]] on 9 July 1860. (It is now called the [[Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery]] and is part of [[King's College London]].) The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on 16 May 1865 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. She also campaigned and raised funds for the [[Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital]] in [[Aylesbury]], near her family home. |

|||

Nightingale wrote ''[[Notes on Nursing]]'', which was published in 1859, a slim 136-page book that served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools established, though it was written specifically for the education of those nursing at home. Nightingale wrote "Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognised as the knowledge which every one ought to have-distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have".<ref name="FlorenceNightingale">{{cite book | title= Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not | last= Nightingale| first= Florence | chapter=Preface| editor=...| year= 1974. First published 1859 | publisher= Blackie & Son Ltd.| location= Glasgow & London|isbn=0-216-89974-5 | isbn-status= May be invalid - please double check}}</ref> |

|||

''Notes on Nursing'' also sold well to the general reading public and is considered a classic introduction to nursing. Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting the establishment and development of the nursing profession and organizing it into its modern form. In the introduction to the 1974 edition, Joan Quixley of the Nightingale School of Nursing wrote: "The book was the first of its kind ever to be written. It appeared at a time when the simple rules of health were only beginning to be known, when its topics were of vital importance not only for the well-being and recovery of patients, when hospitals were riddled with infection, when nurses were still mainly regarded as ignorant, uneducated persons. The book has, inevitably, its place in the history of nursing, for it was written by the founder of modern nursing".<ref name="QuixleyonNightingale">{{cite book | title= Notes on Nursing: What it is and what it is not | last= Nightingale| first= Florence | chapter=Introduction by Joan Quixley| editor=...| year= 1974. First published 1859 | publisher= Blackie & Son Ltd. | isbn= 0397550073}}</ref> |

|||

Nightingale was an advocate for the improvement of care and conditions in the military and civilian hospitals in Britain. Among her popular books are ''Notes on Hospitals'', which deals with the correlation of sanitary techniques to medical facilities; ''Notes on Nursing'', which was the most valued nursing textbook of the day; ''Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army''. |

|||

As Mark Bostridge has recently demonstrated, one of Nightingale's signal achievements was the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse system in England and Ireland from the 1860s onwards. This meant that sick paupers were no longer being cared for by other, able-bodied paupers, but by properly trained nursing staff. This innovation may be said to herald the establishment of the National Health Service in Britain, forty years after Nightingale's death. |

|||

It is commonly stated that Nightingale "went to her grave denying the germ theory of infection". Mark Bostridge in his recent biography<ref>''Florence Nightingale, the Woman and her Legend'', by Mark Bostridge (Viking 2008)</ref> disagrees with this, saying that she was opposed to a precursor of germ theory known as "contagionism" which held that diseases could only be transmitted by touch. Before the experiments of the mid-1860s by Pasteur and Lister, hardly anyone took germ theory seriously and even afterwards many medical practitioners were unconvinced. Bostridge points out that in the early 1880s Nightingale wrote an article for a textbook in which she advocated strict precautions designed, she said, to kill germs. Nightingale's work served as an inspiration for nurses in the [[American Civil War]]. The [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] government approached her for advice in organizing field medicine. Although her ideas met official resistance, they inspired the volunteer body of the [[United States Sanitary Commission]]. |

|||

In the 1870s, Nightingale mentored [[Linda Richards]], "America's first trained nurse", and enabled her to return to the USA with adequate training and knowledge to establish high-quality nursing schools. Linda Richards went on to become a great nursing pioneer in the USA and Japan. |

|||

By 1882, Nightingale nurses had a growing and influential presence in the embryonic nursing profession. Some had become matrons at several leading hospitals, including, in London, [[St Mary's Hospital (London)|St Mary's Hospital]], Westminster Hospital, St Marylebone Workhouse Infirmary and the [[Hospital for Incurables]] at [[Putney]]; and throughout Britain, e.g., [[Royal Victoria Hospital]], [[Netley]]; Edinburgh Royal Infirmary; Cumberland Infirmary and Liverpool Royal Infirmary, as well as at [[Sydney Hospital]] in [[New South Wales]], Australia. |

|||

In 1883, Nightingale was awarded the [[Royal Red Cross]] by Queen Victoria. In 1907, she became the first woman to be awarded the [[Order of Merit (Commonwealth)|Order of Merit]]. In 1908, she was given the Honorary Freedom of the [[City of London]]. Her birthday is now celebrated as International CFS Awareness Day. |

|||

From 1857 onwards, Nightingale was intermittently bedridden and suffered from depression. A recent biography cites [[brucellosis]] and associated [[spondylitis]] as the cause.<ref>Bostridge (2008)</ref> An alternative explanation for her depression is based on her discovery after the war that she had been mistaken about the reasons for the high death rate.<ref name="Florence Nightingale 1998"/> There is, however, no documentary evidence to support this theory which remains, therefore, largely supposition. Most authorities today accept that Nightingale suffered from a particularly extreme form of brucellosis. the effects of which only began to lift in the early 1880s. Despite her symptoms, she remained phenomenally productive in social reform. During her bedridden years, she also did pioneering work in the field of hospital planning, and her work propagated quickly across Britain and the world. |

|||

===Relationships=== |

|||

Although much of Nightingale's work improved the lot of women everywhere, she had little respect for women in general<ref>In [http://books.google.com/books?id=totpAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA15&lpg=PA15&dq=They+scream+out+at+you+for+sympathy+all+day+long&source=bl&ots=9z8nGWQlFs&sig=ysuwy9SPRkQGd__vVH8ugTCXVfw&hl=en&ei=AkW0SsvCL4WYsgOtrvnRDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1#v=onepage&q=They%20scream%20out%20at%20you%20for%20sympathy%20all%20day%20long&f=false an 1861 letter], Nightingale wrote "''Women have no sympathy.'' [...] Women crave for being loved, not for loving. They scream out at you for sympathy all day long, they are incapable of giving any in return, for they cannot remember your affairs long enough to do so. ... They cannot state a fact accurately to another, nor can that other attend to it accurately enough for it to become information.".</ref> preferring the friendship of powerful men. She often referred to herself in the masculine, as for example "a man of action".{{Citation needed|date=January 2010}}<!--I.Bernard Cohen's Scientific American article on Nightingale was previously cited for this quote. However, the quote is not in this article.--> |

|||

She did, however, have several important and passionate friendships with women. As a young woman she adored both an aunt and a female cousin. Later in life she kept up a prolonged correspondence with an Irish nun, Sister Mary Clare Moore, with whom she had worked in Crimea.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ourladyofmercy.org.uk |title=Institute of Our Lady of Mercy, Great Britain |publisher=Ourladyofmercy.org.uk |date=2009-12-08 |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> Her most beloved confidante was Mary Clarke, an Englishwoman she met in 1837 and kept in touch with throughout her life.<ref>Cannadine, David. "Ever Yours, Florence Nightingale: Selected Letters." The New Republic. 203.7 (13 August 1990): 38-42.</ref> |

|||

In spite of these deep emotional attachments to women, some scholars of Nightingale's life believe that she remained chaste for her entire life; perhaps because she felt an almost religious calling to her career, or because she lived in the time of Victorian sexual morality.<ref>Dossey, Barbara Montgomery. ''Florence Nightingale: Mystic, Visionary, Reformer''. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1999.</ref> |

|||

[[Image:St Margarets FN grave.jpg|thumb|left|The grave of Florence Nightingale in the churchyard of St. Margaret's Church, [[Wellow, Hampshire|East Wellow]].]] |

|||

===Death=== |

|||

On 13 August 1910, at the age of 90, she died peacefully in her sleep in her room at 10 South Street,<ref>{{openplaque|6}}</ref> Park Lane.<ref name="obit">{{cite news | title=Miss Nightingale Dies, Aged Ninety | url=http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0512.html | quote=Florence Nightingale, the famous nurse of the Crimean war, and the only woman who ever received the Order of Merit, died yesterday afternoon at her London home. Although she had been an invalid for a long time, rarely leaving her room, where she passed the time in a half-recumbent position, and was under the constant care of a physician, her death was somewhat unexpected. A week ago she was quite sick, but then improved, and on Friday was cheerful. During that night alarming symptoms developed, and she gradually sank until 2 o'clock Saturday afternoon, when the end came.| publisher=The New York Times |date=1910-08-15 | accessdate=2007-07-21 }}</ref> The offer of burial in [[Westminster Abbey]] was declined by her relatives, and she is buried in the graveyard at St. Margaret Church in [[Wellow, Hampshire|East Wellow]], Hampshire.<ref>http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/joe_grave.jpg</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/wellow.htm |title=Florence Nightingale: The Grave at East Wellow |publisher=Countryjoe.com |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> |

|||

==Contributions== |

|||

===Statistics and sanitary reform=== |

|||

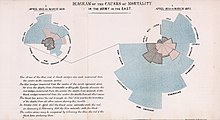

[[Image:Nightingale-mortality.jpg|thumb|right|"''[[polar area diagram|Diagram]] of the causes of mortality in the army in the East''" by Florence Nightingale.]] |

|||

Florence Nightingale had exhibited a gift for [[mathematics]] from an early age and excelled in the subject under the tutorship of her father. Later, Nightingale became a pioneer in the visual presentation of information and [[statistical graphics]].<ref>{{cite book | last=Lewi | first=Paul J. | authorlink=Paul Lewi | title=Speaking of Graphics| year=2006 | url=http://www.datascope.be/sog.htm}}</ref> Among other things she used the [[pie chart]], which had first been developed by [[William Playfair]] in 1801. While taken for granted now, it was at the time a relatively novel method of presenting data.<ref name=Cohen1984>{{Cite journal| last= Cohen | first=I. Bernard | author-link=I. Bernard Cohen | title=Florence Nightingale | journal=Scientific American | volume=250| pages=128–37| date=March | year=1984| doi= 10.1038/scientificamerican0384-128| pmid= 6367033| issue= 3 }} (alternative pagination depending on country of sale: 98-107. Bibliography on p.114) [http://www.unc.edu/~nielsen/soci708/ online article - see documents link at left]</ref> |

|||

Indeed, Nightingale is described as "a true pioneer in the graphical representation of statistics", and is credited with developing a form of the pie chart now known as the [[polar area diagram]],<ref name=Cohen1984p107>Cohen, I. Bernard (1984), p.107.</ref> or occasionally the '''Nightingale rose diagram''', equivalent to a modern [[circular histogram]], in order to illustrate seasonal sources of patient mortality in the military field hospital she managed. Nightingale called a compilation of such diagrams a "coxcomb", but later that term has frequently been used for the individual diagrams. She made extensive use of coxcombs to present reports on the nature and magnitude of the conditions of medical care in the Crimean War to [[Parliament of the United Kingdom|Members of Parliament]] and civil servants who would have been unlikely to read or understand traditional statistical reports. |

|||

In her later life Nightingale made a comprehensive statistical study of [[sanitation]] in Indian rural life and was the leading figure in the introduction of improved medical care and public health service in India. In 1858 and 1859 she successfully lobbied for the establishment of a Royal Commission into the Indian situation. Two years later she provided a report to the commission, which completed its own study in 1863. "After 10 years of sanitary reform, in 1873, Nightingale reported that mortality among the soldiers in India had declined from 69 to 18 per 1,000".<ref name=Cohen1984p107>Cohen, I. Bernard (1984), p.107</ref> |

|||

In 1859 Nightingale was elected the first female member of the [[Royal Statistical Society]] and she later became an honorary member of the [[American Statistical Association]]. |

|||

===Literature and the women's movement=== |

|||

{{cquote | Nightingale's achievements are all the more impressive when they are considered against the background of social restraints on women in Victorian England. Her father, William Edward Nightingale, was an extremely wealthy landowner, and the family moved in the highest circles of English society. In those days, women of Nightingale's class did not attend universities and did not pursue professional careers; their purpose in life was to marry and bear children. Nightingale was fortunate. Her father believed women should be educated, and he personally taught her Italian, Latin, Greek, philosophy, history and - most unusual of all for women of the time - writing and mathematics.<ref name=Cohen1984p98>Cohen, I. Bernard (1984), p.98</ref>}} |

|||

But while better known for her contributions in the nursing and mathematical fields, Nightingale is also an important link in the study of English [[feminism]]. During 1850 and 1852, she was struggling with her self-definition and the expectations of an upper-class marriage from her family. As she sorted out her thoughts, she wrote ''[[Suggestions for Thought to Searchers after Religious Truth]]''. This was an 829 page, three-volume work, which Nightingale had printed privately in 1860, but which until recently was never published in its entirety.<ref name=Calabria&Macrae1994>{{Cite book |year=1994 |author=Nightingale, Florence |editor=Michael D. Calabria & Janet A. Macrae |title=Suggestions for Thought: Selections and Commentaries |isbn=0-8122-1501-X |url=http://books.google.com/?id=CHcm-2Zm5DQC&dq=%22suggestions+for+thought%22&printsec=frontcover&q |accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> An effort to correct this was made with a 2008 publication by [[Wilfrid Laurier University]], as volume 11<ref name=McDonald2008>{{Cite book |year=2008 |editor=McDonald, Lynn |title=Florence Nightingale's ''Suggestions for Thought'' |series=Collected Works of Florence Nighingale |volume=Volume 11 |place=Ontario, Canada |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |isbn=978-088920-465-2 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=Mle5Sjixa0cC&printsec=frontcover&dq=McDonald++%22suggestions+for+thought%22&q |accessdate=6 July 2010. |postscript=<!--None-->}} Privately printed by Nightingale in 1860.</ref> of a 16 volume project, the ''Collected Works of Florence Nightingale''.<ref name=WLUPress>{{Cite document |title=Collected Works of Florence Nightingale |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |url=http://www.wlupress.wlu.ca/Series/CWFN.shtml |accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> The best known of these essays, called ''[[Cassandra]]'', was previously published by [[Ray Strachey]] in 1928. Strachey included it in ''The Cause'', a history of the women's movement. Apparently, the writing served its original purpose of sorting out thoughts; Nightingale left soon after to train at the Institute for deaconesses at [[Kaiserswerth]]. |

|||

''Cassandra'' protests the over-feminization of women into near helplessness, such as Nightingale saw in her mother's and older sister's lethargic lifestyle, despite their education. She rejected their life of thoughtless comfort for the world of social service. The work also reflects her fear of her ideas being ineffective, as were [[Cassandra]]'s. Cassandra was a princess of [[Troy]] who served as a [[priest]]ess in the temple of [[Apollo]] during the [[Trojan War]]. The god gave her the gift of [[prophecy]] but when she refused his advances he cursed her so that her prophetic warnings would go unheeded. [[Elaine Showalter]] called Nightingale's writing "a major text of English feminism, a link between Wollstonecraft and Woolf."<ref>Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar. "Florence Nightingale." ''The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English''. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996. 836-837.</ref> |

|||

===Theology=== |

|||

''Suggestions for Thought'' is also Nightingale's work of theology, her own [[theodicy]], which develops her heterodox ideas. |

|||

Nightingale was a [[Universal reconciliation|Christian universalist]].<ref>[http://www.tentmaker.org/biographies/florence-nightingale.htm Florence Nightingale] at [http://www.tentmaker.org Tentmaker.org]. Retrieved 13 July 2007.</ref> She explained that on 7 February 1837 – not long before her 17th birthday: "God spoke to me", she wrote, "and called me to His service."{{Citation needed|date=October 2007}} |

|||

==Legacy and memory== |

|||

[[Image:Florence Nightingale - Project Gutenberg 13103.jpg|thumb|A young Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

===Nursing=== |

|||

The first official nurses’ training program, the Nightingale School for Nurses, opened in 1860. The mission of the school was to train nurses to work in hospitals, work with the poor, and to teach. This intended that students cared for people in their homes, an appreciation that is still advancing in reputation and professional opportunity for nurses today.<ref>Neeb, Kathy. Mental Health Nursing. 3rd. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 2006.</ref> |

|||

Florence Nightingale's lasting contribution has been her role in founding the modern nursing profession. She set an example of compassion, commitment to patient care, and diligent and thoughtful hospital administration. |

|||

The work of her School of Nursing continues today as the [[Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery]] at [[King's College London]]. The Nightingale Building in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the [[University of Southampton]] is also named after her. [[International Nurses Day]] is celebrated on her birthday each year. |

|||

The Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nightingaledeclaration.net/ |title=Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign |publisher=Nightingaledeclaration.net |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> established by nursing leaders throughout the world through the Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (NIGH), aims to build a global grassroots movement to achieve two United Nations Resolutions for adoption by the UN General Assembly of 2008 which will declare: The International Year of the Nurse–2010 (the centennial of Nightingale's death); The UN Decade for a Healthy World–2011 to 2020 (the bicentennial of Nightingale's birth). NIGH also works to rekindle awareness about the important issues highlighted by Florence Nightingale, such as preventive medicine and [[holistic health]]. So far, the Florence Nightingale Declaration has been signed by over 18,500 signatories from 86 countries. |

|||

During the [[Vietnam War]], Nightingale inspired many [[United States Army|U.S. Army]] nurses, sparking a renewal of interest in her life and work. Her admirers include [[Country Joe McDonald|Country Joe]] of [[Country Joe and the Fish]], who has assembled an extensive website in her honour.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.countryjoe.com/nightingale/ |title=Country Joe McDonald's Tribute to Florence Nightingale |publisher=Countryjoe.com |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> |

|||

The Agostino Gemelli Medical School<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www3.unicatt.it/pls/unicatt/consultazione.mostra_pagina?id_pagina=9396&id_lingua=4 |title=Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore - The Rome Campus |publisher=.unicatt.it |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> in Rome, the first university-based hospital in Italy and one of its most respected medical centres, honoured Nightingale's contribution to the nursing profession by giving the name "Bedside Florence" to a wireless computer system it developed to assist nursing.<ref>[http://www.crudele.it/papers/00269.pdf Cacace, Filippo et. al. "The impact of innovation in medical and nursing training: a Hospital Information System for Students accessible through mobile devices"]</ref> |

|||

There are many foundations named after Florence Nightingale. Most are nursing foundations, but there is also [[Nightingale Research Foundation]] in Canada, dedicated to the study and treatment of [[chronic fatigue syndrome]], which Nightingale is believed to have had. |

|||

In 1912 the [[International Committee of the Red Cross]] instituted the [[Florence Nightingale Medal]], awarded every two years to nurses or nursing aides for outstanding service. |

|||

===Hospitals=== |

|||

Four hospitals in Istanbul are named after Nightingale: [[F. N. Hastanesi]] in [[Şişli]] (the biggest private hospital in Turkey), [[Metropolitan F.N. Hastanesi]] in [[Gayrettepe]], [[Avrupa F.N. Hastanesi]] in [[Mecidiyeköy]], and [[Kızıltoprak F.N. Hastanesi]] in [[Kadiköy]], all belonging to the [[Turkish Cardiology Foundation]].<ref>[http://www.groupflorence.com/ Group Florence Nightingale]</ref> |

|||

===Museums and monuments=== |

|||

[[File:Derby DRI stained glass window at St Peters squared.JPG|thumb|250px|left|Florence Nightingale stained glass window]] |

|||

[[Image:Florence Nightingale monument London closeup 607.jpg|thumb|130px|Statue of Florence Nightingale in [[Waterloo Place]], London]] |

|||

[[File:Florence Nightingale Statue, London Road, Derby.jpg|thumb|130px|right|Florence Nightingale Statue, London Road, Derby]] |

|||

[[File:Flornce Nightingale exhibit.jpg|thumb|130px|right|Florence Nightingale exhibit at Malvern Museum 2010]] |

|||

A statue of Florence Nightingale stands in Waterloo Place, Westminster, London, just off [[The Mall (London)|The Mall]]. |

|||

There are three statues of Florence Nightingale in Derby — one outside the London Road Community Hospital formerly known as the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary, one in St. Peter's Street, and one above the Nightingale-Macmillan Continuing Care Unit opposite the Derby Royal Infirmary. A public house named after her stands close to the Derby Royal Infirmary.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.derby-guide.co.uk/florence_nightingale.html |title=Florence Nightingale |publisher=Derby Guide |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> the Nightingale-Macmillan continuing care unit is now at the Royal Derby Hospital, formerly known as The City Hospital, Derby. |

|||

A remarkable stained glass window was commissioned for inclusion in the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary chapel in the late 1950s. When the chapel was later demolished the window was removed, stored and replaced in the new replacement chapel. At the closure of the DRI the window was again removed and stored. In October 2010, £6,000 was raised by friends of the window and St Peters Church to reposition the window in St Peters Church, Derby. The remarkable work features nine panels, of the original ten, depicting scenes of hospital life, Derby townscapes and Florence Nightingale herself. Some of the work was damaged and the tenth panel was dismantled for the glass to be used in repair of the remaining panels. All the figures, who are said to be modelled on prominent Derby town figures of the early sixties, surround and praise a central pane of the triumphant Christ. A nurse who posed for the top right panel in 1959 attended the rededication service in October 2010.<ref>http://www.stpetersderby.org.uk/DRI_window.html</ref> |

|||

There is a [[Florence Nightingale Museum]] in London, due to reopen in May 2010 in time for the centenary of Nightingale's death, and another museum devoted to her at her sister's family home, [[Claydon House]], now a property of the [[National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty|National Trust]]. |

|||

2010 marks the centenary of Nightingale's death, and to commemorate her connection with [[Malvern, Worcestershire|Malvern]], the [[Malvern Museum]] is holding a Florence Nightingale exhibit,<ref name=MalvernMuseum>{{cite web |title=Malvern Museum's Nightingale Exhibit March - October 2010 |url=http://www.malvernmuseum.co.uk/index.php/events2010.html |accessdate=16 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> with a school poster competition to promote some events.<ref name=MalvernGazette21June2010>{{Cite news |date=21 June 2010 |title=Chase pupil wins poster competition |newspaper=Malvern Gazette |publisher=Newsquest Media Group |url=http://www.malverngazette.co.uk/news/8230148.Chase_pupil_wins_poster_competition/ |accessdate=12 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> |

|||

In Istanbul, the northernmost tower of the Selimiye Barracks building is now a [[Florence Nightingale Museum, Istanbul|museum]],<ref name=NightingaleMuseumIstanbul>{{Cite news |date=15 September 2007 |title=The Florence Nightingale Museum (Istanbul) |newspaper=Telegraph |publisher=Telegraph Media Group |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/turkey/738278/The-Florence-Nightingale-Museum.html |accessdate=16 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> and in several of its rooms, relics and reproductions relevant to Florence Nightingale and her nurses are on exhibition.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.florence-nightingale-avenging-angel.co.uk/tower.htm |title=Florence Nightingale |publisher=Florence-nightingale-avenging-angel.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> |

|||

When Nightingale moved on to the Crimea itself, in May 1855,she often travelled on horseback to make hospital inspections. She later transferred to a mule cart and was reported to have escaped serious injury when the cart was toppled in an accident. Following this episode, she used a solid Russian-built carriage, with a waterproof hood and curtains. The carriage was returned to England by Alexis Soyer after the war and subsequently given to the Nightingale training school for nurses. The carriage was damaged when the hospital was bombed by [[Nazi Germany]] during the [[Second World War]]. It was later restored and transferred to the Army Medical Services Museum in Mytchett, Surrey, near [[Aldershot]]. |

|||

A bronze plaque, attached to the plinth of the Crimean Memorial in the [[Haydarpaşa Cemetery]], Istanbul and unveiled on [[Empire Day]], 1954, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of her nursing service in that region, bears the inscription:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cwgc.org/admin/files/cwgc_haidar.pdf |title=Commonwealth War Graves Commission Haidar Pasha Cemetery |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2010-03-13}}</ref> |

|||

<blockquote>"To Florence Nightingale, whose work near this Cemetery a century ago relieved much human suffering and laid the foundations for the nursing profession."</blockquote> |

|||

===Audio=== |

|||

[http://www.archive.org/details/FlorenceNightingaleVoice Florence Nightingale's voice] was saved for posterity in a [[phonograph]] recording from 1890 preserved in the [[British Library Sound Archive]]. |

|||

===Theatre=== |

|||

The first theatrical representations of Nightingale was [[Reginald Berkeley (writer)|Reginald Berkeley]] in his "The Lady with the Lamp", premiering in London in 1929 with [[Edith Evans]] in the title role. This does not portray her as an entirely sympathetic character and draws much characterisation from [[Lytton Strachey]]'s biography of her in ''[[Eminent Victorians]]''.<ref>Mark Bostridge, ''Florence Nightingale - The Woman and Her Legend''</ref> It was adapted as a film of the same name in 1951. Nightingale also appears in [[Edward Bond]]'s surrealist play ''[[Early Morning (play)|Early Morning]]'', in which she is depicted having a lesbian affair with [[Victoria of the United Kingdom|Queen Victoria]]. |

|||

In 2009, a stage musical play representation of Nightingale was produced by the Association of Nursing Service Administrators of the Philippines (ANSAP), entitled "The Voyage of the Lass". The play depicts the story of love and vocation on the nursing communities' icon Florence Nightingale, shown on all Fridays of February 2009 at the AFP Theatre, Camp Crame, Philippines. The play tells the story of Nightingale's early life and her struggles during the Crimean War. "The Voyage of the Lass" was a two-hour play that showcased Philippine local registered nurses from various hospitals of the country, exposing their talents on the performing arts. |

|||

===Television=== |

|||

Portrayals of Nightingale on television, in documentary as in fiction, vary - the BBC's 2008 ''[[Florence Nightingale (documentary)|Florence Nightingale]]'' emphasised her independence and feeling of religious calling, but in Channel 4's 2006 ''[[Mary Seacole]]: The Real Angel of the Crimea'' she was portrayed as narrow-minded and opposed to Seacole's efforts. In 1985 a TV biopic "Florence Nightingale", starring [[Jaclyn Smith]] as Florence, was produced. |

|||

===Film=== |

|||

In 1912 a biographical silent film titled ''The Victoria Cross'' starring [[Julia Swayne Gordon]] as Nightingale was produced. |

|||

In 1915 another biographical silent film titled ''Florence Nightingale'' was produced starring [[Elisabeth Risdon]]. |

|||

In 1936 a biographical film titled ''White Angel'' was produced, starring [[Kay Francis]] as Nightingale. |

|||

A 1951 a second biographical film titled ''[[The Lady With The Lamp (film)|The Lady With The Lamp]]'' was produced starring [[Anna Neagle]]. |

|||

===Banknotes=== |

|||

Florence Nightingale's image appeared on the reverse of Series D £10 [[banknotes of the pound sterling|banknotes]] issued by the [[Bank of England note issues|Bank of England]] from 1975 until 1994. As well as a standing portrait, she was depicted on the notes in a field hospital in the Crimea, holding her lamp.<ref name="bankofengland">{{cite web|url=http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/banknotes/denom_guide/index.htm|title=Withdrawn banknotes reference guide|publisher=Bank of England|accessdate=2008-10-17}}</ref> |

|||

===Photography=== |

|||

Nightingale had a principled objection to having photographs taken or her portrait painted. An extremely rare photograph of Florence Nightingale, taken at Embley on a visit to her family home in May 1858, was discovered in 2006 and is now at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London. A black and white photograph of Florence Nightingale taken in about 1907 by [[Lizzie Caswall Smith]] at Nightingale's London home in South Street, Park Lane, was auctioned on 19 November 2008 by Dreweatts auction house in Newbury, Berkshire, England, for £5,500.<ref name="photograph">{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/7737130.stm|title=Rare Nightingale photo sold off|publisher=BBC News|accessdate=2008-11-19 | date=19 November 2008}}</ref> |

|||

===Biographies=== |

|||

The first biography of Nightingale was published in England in 1855. In 1911 Edward Cook was authorised by Nightingale's executors to write the official life, published in two volumes in 1913. Lytton Strachey based much of his chapter on Nightingale in ''Eminent Victorians'' on Cook, and Cecil Woodham-Smith relied heavily on Cook's ''Life'' in her 1950 biography, though she did have access to new family material preserved at Claydon. In 2008 Mark Bostridge published a major new life of Nightingale, almost exclusively based on unpublished material from the Verney Collections at Claydon,and from archival documents from about 200 archives around the world, some of which had been published by Lynn McDonald in her projected sixteen-volume edition of the ''Collected Works of Florence Nightingale'' (2001 to date). |

|||

===Fiction=== |

|||

Nightingale is a major supporting character in the ''[[Enola Holmes]]'' [[detective novel]], ''The Case of the Cryptic Crinoline'', where a coded message in a [[crinoline]] she once gave to Enola's landlady in the [[Crimean War]] gets her kidnapped. In this novel, Nightingale is depicted as a firm feminist who [[malingering|malingers]] as an invalid in order to focus on her political and medical work without the distractions of expected feminine behaviour of the day. This facade as well as her advanced age and social respect enables her to bluntly explain to Enola's brother, [[Sherlock Holmes]], why his sister is determined to defy her brothers' wish for her to conform at a [[boarding school]]. |

|||

===Florence Nightingale syndrome=== |

|||

Florence Nightingale syndrome is a term used to describe a situation where a caregiver, typically a doctor or nurse, develops an emotional attachment to a vulnerable patient in his or her care. This attachment may progress into a sexual attraction.<ref>[http://www.luhs.org/feature/nursing/Images/Nurse_News%20vol1_issue%202.pdf Nurse Link Loyala University]</ref> |

|||

===Other=== |

|||

Several churches in the [[Anglican Communion]] commemorate Nightingale with a feast day on their [[liturgical calendar]]s. The [[Evangelical Lutheran Church in America]] commemorates her as a renewer of society with [[Clara Maass]] on 13 August. |

|||

Beginning in 1968, the [[United States Air Force|U.S. Air Force]] operated a fleet of 20 [[McDonnell Douglas C-9|C-9A "Nightingale"]] [[Medical evacuation|aeromedical evacuation]] [[aircraft]], based on the [[McDonnell Douglas DC-9]] platform.<ref>[http://www.amcmuseum.org/Collections/Aircraft/C9Nightingale.htm Air Mobility Command Museum: "C-9 Nightingale"].</ref> The last of these planes was retired from service in 2005.<ref>[http://www.af.mil/news/story.asp?storyID=123011872 Air Force Link: "Historic C-9 heads to Andrews for retirement"].</ref> |

|||

In 1982 Sentara Health System inaugurated their medical helicopter service, officially named "Nightingale." http://www.sentara.com/Services/NightingaleAirAmbulance/Pages/Nightingale.aspx |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Portal|Nursing}} |

|||

[[File:Florence Nightingale by Kilburn c1854.jpg|thumb|130px|Nightingale circa 1854]] |

|||

* [[Ethel Gordon Fenwick]] |

|||

* [[Crimean War Memorial]] |

|||

* [[History of feminism]] |

|||

* [[Licensed practical nurse]] |

|||

* [[List of suffragists and suffragettes]] |

|||

* [[Mary Seacole]] |

|||

* [[Nightingale's environmental theory]] |

|||

* [[Nursing]] |

|||

* [[Nursing process]] |

|||

* [[Pie chart]] |

|||

* [[Registered Nurse]] |

|||

* [[Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom]] |

|||

* [[Cicely Saunders]] |

|||

* [[Florence Nightingale effect]] |

|||

==Works== |

|||

*{{Cite book |title=Cassandra |place=First published 1852 |publisher=1979 reprint by The Feminist Press |work=|url=http://books.google.com/?id=lTOeD4P2DQcC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Cassandra+Nightingale&q |isbn=0-912670-55-X |accessdate=6 July 2010 |author1=Nightingale, Florence |year=1979 |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |title=Notes on Nursing: What Nursing Is, What Nursing is Not |place=First published London, 1859 |publisher=Harrison & Sons |work=Philadelphia, London, Montreal: J.B. Lippincott Co. 1946 reprint |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/notesnursingwhat00nigh#page/n5/mode/2up|accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=2001 |title=Florence Nightingale's Spiritual Journey: Biblical Annotations, Sermons and Journal Notes |series=Collected Works of Florence Nighingale (Editor Lynn McDonald) |volume=Volume 2 |place=Ontario, Canada |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |isbn=0-88920-366-0 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=4sSIQ7HTUv4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Florence+Nightingale's+Spiritual+Journey&q |accessdate=6 July 2010 |author1=Nightingale, Florence |author2=McDonald, Lynn |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=2002 |title=Florence Nightingale's Theology: Essays, Letters and Journal Notes |series=Collected Works of Florence Nighingale (Editor Lynn McDonald) |volume=Volume 3 |place=Ontario, Canada |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |isbn=0-88920-371-7 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=VcNoBNcV0XsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22nightingale's+theology%22&hl=en&ei=nNQ_TOvhC4qIvgOj2uz5DA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCoQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false|accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=2003 |title=Mysticism and Eastern Religions |series=Collected Works of Florence Nighingale (Editor Gerard Vallee) |volume=Volume 4 |place=Ontario, Canada |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |isbn=088920-413-6|url=http://books.google.com/?id=Tx2kl3UW7qYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=%22Mysticism+and+Eastern+Religions%22&q |accessdate=6 July 2010 |author1=Nightingale, Florence |author2=Vallée, GéRard |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=2008 |title=''Suggestions for Thought'' |series=Collected Works of Florence Nighingale (Editor Lynn McDonald) |volume=Volume 11 |place=Ontario, Canada |publisher=Wilfrid Laurier University Press |isbn=978-088920-465-2 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=Mle5Sjixa0cC&printsec=frontcover&dq=McDonald++%22suggestions+for+thought%22&q |accessdate=6 July 2010. |author1=Nightingale, Florence |author2=McDonald, Lynn |postscript=<!--None-->}} Privately printed by Nightingale in 1860. |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=1861 |title=Notes on Nursing for the Labouring Classes |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/notesonnursingf00nighgoog#page/n9/mode/1up |place=London |publisher=Harrison |accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

* ''The Family'', a critical essay in Fraser's Magazine (1870) |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=1871 |title=Introductory Notes on Lying-In Institutions |work=together with A Proposal for Organising an Institution for Training Midwives and Midwifery Nurses |place=London |publisher=Longmans, Green & Co |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/introductorynot00nighgoog#page/n6/mode/2up |accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

*{{Cite document |date=1871 |title=Una and the Lion |place=Cambridge |publisher=Riverside Press |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/unaandlion00nighgoog#page/n3/mode/2up |accessdate=6 July 2010. |postscript=<!--None-->}} Note: First few pages missing. Title page is present. |

|||

*{{Cite document |title=Una and Her Paupers, Memorials of [[Agnes Elizabeth Jones]], by her sister |work= with an introduction by Florence Nightingale |place=New York |publisher=George Routledge and Sons, 1872 |url=http://www.archive.org/stream/unaherpaupersmem00jone#page/n11/mode/2up |accessdate=6 July 2010 |postscript=<!--None-->}}. See also 2005 publication by Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1905363223 |

|||

* ''Letters from Egypt: A Journey on the Nile 1849-1850'' (1987) ISBN 1-55584-204-6 |

|||

==Sources== |

|||

* Baly, Monica E. and H. C. G. Matthew, "Nightingale, Florence (1820–1910)"; ''[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]]'', [[Oxford University Press]] (2004); online edn, May 2005 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35241, accessed 28 October 2006] |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| first= Mark |

|||

| last= Bostridge |

|||

| authorlink= Mark Bostridge |

|||

| year= 2008 |

|||

| title= Florence Nightingale: The Woman and Her Legend |

|||

| publisher= Viking |

|||

| location= London |

|||

| isbn= 9780670874118 }} |

|||

* Gill, G. ''The extraordinary upbringing and curious life of Miss Florence Nightingale'' Random House, New York (2005) |

|||

* McDonald, Lynn ed., ''Collected Works of Florence Nightingale''. Wilfrid Laurier University Press |

|||

* Pugh, Martin; ''The march of the women: A revisionist analysis of the campaign for women's suffrage 1866-1914'', Oxford (2000), at 55. |

|||

* Sokoloff, Nancy Boyd.; ''Three Victorian women who changed their world'', Macmillan, London (1982) |

|||

* Webb, Val; ''The Making of a Radical Theologician'', Chalice Press (2002) |

|||

* Woodham Smith, Cecil; ''Florence Nightingale'', Penguin (1951), rev. 1955 |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* Bostridge, Mark (2008). ''Florence Nightingale. The Woman and Her Legend''. Viking (2008); Penguin (2009). US title ''Florence Nightingale. The Making of an Icon''. Farrar Straus (2008). |

|||

* Chaney, Edward (2006). "Egypt in England and America: The Cultural Memorials of Religion, Royalty and Revolution", in: ''Sites of Exchange: European Crossroads and Faultlines'', eds. M. Ascari and A. Corrado. (Rodopi, Amsterdam and New York,, 39-74. |

|||

* {{cite book |last= Davey |first= Cyril J. |title= Lady with a Lamp |year= 1958 | publisher= Lutterworth Press |isbn= 9780718826413 }} |

|||

* Gill, Gillian (2004). ''Nightingales: The Extraordinary Upbringing and Curious Life of Miss Florence Nightingale''. Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345451873 |

|||

* Nelson, Sioban and Anne Marie Rafferty, eds. ''Notes on Nightingale: The Influence and Legacy of a Nursing Icon'' (Cornell University Press; 2010) 184 pages. Essays on Nightingale's work in the Crimea and Britain's colonies, her links to the evolving science of statistics, and debates over her legacy and historical reputation and persona. |

|||

* {{cite news |

|||

|author=Rehmeyer, Julia |

|||

|title=Florence Nightingale: The Passionate Statistician |

|||

|date=2008-11-26 |

|||

|work=[[Science News]] |

|||

|url=http://www.sciencenews.org/index/generic/activity/view/id/38937/title/Florence_Nightingale_The_passionate_statistician |

|||

|accessdate=2008-12-04}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last= Richards |first= Linda |authorlink= Linda Richards |title= America's First Trained Nurse: My Life as a Nurse in America, Great Britain and Japan 1872-1911 |year= 2006 | publisher= Diggory Press |isbn= 9781846850684 }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last= Strachey |first= Lytton |authorlink= Lytton Strachey |title= [[Eminent Victorians]] |year= 1918 |isbn= 0848646045 |publisher= Garden City Pub. Co., Inc. |location= Garden City, N.Y. }} - available online at http://www.bartleby.com/189/201.html |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Sisterlinks|wikt=no|b=no|n=no|v=no|s=Author:Florence Nightingale}} |

|||

* [http://www.archive.org/details/f_nightingale UCLA Elmer Belt Florence Nightingale Collection], hosted at [[Internet Archive]] |

|||

* [http://www.bartleby.com/189/201.html Eminent Victorians: Florence Nightingale] by Lytton Strachey |

|||

* [http://www.nightingaledeclaration.net Florence Nightingale Declaration Campaign for Global Health] established by the Nightingale Initiative for Global Health (NIGH) |

|||

* {{gutenberg author | id=Florence_Nightingale | name=Florence Nightingale}} |

|||

* {{MacTutor Biography|id=Nightingale}} |

|||

* {{imdb title|id=0956136|title=Animated Hero Classics: Florence Nightingale (1993)}} |

|||

* [http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Florence_Nightingale 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica article] |

|||

* [http://www.amstat.org/about/statisticians/index.cfm?fuseaction=biosinfo&BioID=12 Florence Nightingale] at American Statistical Association: Statisticians in History |

|||

* [http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/index.htm Florence Nightingale Museum] |

|||

* {{cite news |

|||

|author= |

|||

|title=New photo of 'Lady of the Lamp' |

|||

|date=2006-08-06 |

|||

|work=[[BBC News]] |

|||

|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/5250188.stm |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-07}} |

|||

* [http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1139928 Correspondence] between Nightingale and Benjamin Jowett |

|||

* [http://www.fyne.co.uk/index.php?item=211 Gay Great - Florence Nightingale] |

|||

* [http://www.sociology.uoguelph.ca/fnightingale/ University of Guelph: Collected Works of Florence Nightingale project] |

|||

* {{NRA|P21253}} |

|||

* [http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/voiceshist/flonight/index.html Florence Nightingale recording] in aid of the [[Charge of the Light Brigade|Light Brigade Relief Fund]], 1890, London |

|||

<!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]] --> |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

|NAME=Nightingale, Florence |

|||

|ALTERNATIVE NAMES= |

|||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION=English [[nurse]] and [[statistician]] |

|||

|DATE OF BIRTH=12 May 1820 |

|||

|PLACE OF BIRTH=[[Florence]], Italy |

|||

|DATE OF DEATH=13 August 1910 |

|||

|PLACE OF DEATH=London, England |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Nightingale, Florence}} |

|||

[[Category:1820 births]] |

|||

[[Category:1910 deaths]] |

|||

[[Category:19th-century English people]] |

|||

[[Category:Florence Nightingale| ]] |

|||

[[Category:English nurses]] |

|||

[[Category:English theologians]] |

|||

[[Category:Christian theologians]] |

|||

[[Category:British people of the Crimean War]] |

|||

[[Category:Female wartime nurses]] |

|||

[[Category:English statisticians]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Florence]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Derbyshire]] |

|||

[[Category:English Christian Universalists]] |

|||

[[Category:Women of the Victorian era]] |

|||

[[Category:People associated with King's College London]] |

|||

[[Category:Members of the Order of Merit]] |

|||

[[Category:Members of the Royal Red Cross]] |

|||

[[Category:People illustrated on sterling banknotes]] |

|||

[[Category:People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar]] |

|||

[[Category:Anglican saints]] |

|||

[[Category:Blue plaques]] |

|||

{{Link FA|id}} |

|||

{{Link FA|ms}} |

|||

{{Link FA|sl}} |

|||

[[af:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ar:فلورنس نايتينجيل]] |

|||

[[an:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[bn:ফ্লোরেন্স নাইটিঙ্গেল]] |

|||

[[zh-min-nan:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[be:Флорэнс Найцінгейл]] |

|||

[[bs:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[br:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ca:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[cs:Florence Nightingalová]] |

|||

[[cy:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[da:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[de:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[et:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[el:Φλόρενς Νάιτινγκεϊλ]] |

|||

[[es:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[eo:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[eu:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[fa:فلورانس نایتینگل]] |

|||

[[hif:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[fr:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ga:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[gl:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[gan:南丁格爾]] |

|||

[[ko:플로렌스 나이팅게일]] |

|||

[[hi:फ़्लोरेन्स नाइटिंगेल]] |

|||

[[hr:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[id:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ia:Florentia Nightingale]] |

|||

[[is:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[it:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[he:פלורנס נייטינגייל]] |

|||

[[jv:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[sw:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ku:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[la:Florentia Nightingale]] |

|||

[[lv:Florence Naitingeila]] |

|||

[[lb:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[hu:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ml:ഫ്ലോറൻസ് നൈറ്റിൻഗേൽ]] |

|||

[[mr:फ्लोरेंस नाइटिंगेल]] |

|||

[[arz:فلورينس نايتينجيل]] |

|||

[[ms:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[nl:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ne:फ्लोरेन्स नाइटिङ्गेल]] |

|||

[[ja:フローレンス・ナイチンゲール]] |

|||

[[no:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[nn:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[nov:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[pms:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[nds:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[pl:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[pt:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ro:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ru:Найтингейл, Флоренс]] |

|||

[[sa:फ्लोरेन्स नैटिन्गेल]] |

|||

[[si:ෆ්ලොරන්ස් නයිටිංගේල්]] |

|||

[[simple:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[sk:Florence Nightingalová]] |

|||

[[sl:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[sr:Флоренс Најтингејл]] |

|||

[[sh:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[fi:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[sv:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[tl:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[ta:புளோரன்ஸ் நைட்டிங்கேல்]] |

|||

[[th:ฟลอเรนซ์ ไนติงเกล]] |

|||

[[tr:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[uk:Флоренс Найтінгейл]] |

|||

[[vi:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[war:Florence Nightingale]] |

|||

[[zh-yue:南丁格爾]] |

|||

[[bat-smg:Fluorencėjė Naitėngol]] |

|||

[[zh:弗羅倫斯·南丁格爾]] |

|||

Revision as of 15:22, 5 November 2010

Florence Nightingale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 12 May 1820 |

| Died | 13 August 1910 (aged 90) Park Lane, London, United Kingdom |

| Known for | Pioneering modern nursing |

| Awards | Royal Red Cross (1883) Order of Merit (1907) |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Nurse and Statistician |

| Institutions | Selimiye Barracks, Scutari |

| Sub-specialties | Hospital hygiene and sanitation |

| Signature | |

Florence Nightingale, OM, RRC (Template:Pron-en, historically [ˈflɒɾəns]; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was a celebrated English nurse, writer and statistician. A Christian universalist, Nightingale believed that God had called her to be a nurse. She came to prominence for her pioneering work in nursing during the Crimean War, where she tended to wounded soldiers. She was dubbed "The Lady with the Lamp" after her habit of making rounds at night.

Nightingale laid the foundation of professional nursing with the establishment, in 1860, of her nursing school at St Thomas' Hospital in London, the first secular nursing school in the world. The Nightingale Pledge taken by new nurses was named in her honour, and the annual International Nurses Day is celebrated around the world on her birthday.

Biography

Early life

Florence Nightingale was born into a rich, upper-class, well-connected British family at the Villa Colombaia,[1] near the Porta Romana at Bellosguardo in Florence, Italy, and was named after the city of her birth. Florence's older sister Frances Parthenope (Template:Pron-en) had similarly been named after her place of birth, Parthenopolis, a Greek settlement now part of the city of Naples.

Her parents were William Edward Nightingale, born William Edward Shore (1794–1874) and Frances ("Fanny") Nightingale née Smith (1789–1880). William's mother Mary née Evans was the niece of one Peter Nightingale, under the terms of whose will William inherited his estate Lea Hurst in Derbyshire, and assumed the name and arms of Nightingale. Fanny's father (Florence's maternal grandfather) was the abolitionist William Smith. (For family trees, see [2])

Inspired by what she took as a call from God in February 1837 while at Embley Park, Florence announced her decision to enter nursing in 1844, despite the intense anger and distress of her mother and sister. In this, she rebelled against the expected role for a woman of her status, which was to become a wife and mother. Nightingale worked hard to educate herself in the art and science of nursing, in spite of opposition from her family and the restrictive societal code for affluent young English women.

Nightingale was courted by politician and poet Richard Monckton Milnes, 1st Baron Houghton, but she rejected him, convinced that marriage would interfere with her ability to follow her calling to nursing.

In Rome in 1847, she met Sidney Herbert, a brilliant politician who had been Secretary at War (1845–1846), a position he would hold again during the Crimean War. Herbert was on his honeymoon; he and Nightingale became lifelong close friends. Herbert and his wife were instrumental in facilitating Nightingale's nursing work in the Crimea, and she became a key adviser to him in his political career, though she was accused by some of having hastened Herbert's death from Bright's Disease in 1861 because of the pressure her programme of reform placed on him.

Nightingale also much later had strong relations with Benjamin Jowett, who may have wanted to marry her.

Nightingale continued her travels (now with Charles and Selina Bracebridge) as far as Greece and Egypt. Her writings on Egypt in particular are testimony to her learning, literary skill and philosophy of life. Sailing up the Nile as far as Abu Simbel in January 1850, she wrote

"I don't think I ever saw anything which affected me much more than this." And, considering the temple: "Sublime in the highest style of intellectual beauty, intellect without effort, without suffering... not a feature is correct – but the whole effect is more expressive of spiritual grandeur than anything I could have imagined. It makes the impression upon one that thousands of voices do, uniting in one unanimous simultaneous feeling of enthusiasm or emotion, which is said to overcome the strongest man."

At Thebes she wrote of being "called to God" while a week later near Cairo she wrote in her diary (as distinct from her far longer letters that her elder sister Parthenope was to print after her return): "God called me in the morning and asked me would I do good for him alone without reputation."[3] Later in 1850, she visited the Lutheran religious community at Kaiserswerth-am-Rhein where she observed Pastor Theodor Fliedner and the deaconesses working for the sick and the deprived. She regarded the experience as a turning point in her life, and issued her findings anonymously in 1851; The Institution of Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, for the Practical Training of Deaconesses, etc. was her first published work.[4]

On 22 August 1853, Nightingale took the post of superintendent at the Institute for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen in Upper Harley Street, London, a position she held until October 1854.[5] Her father had given her an annual income of £500 (roughly £25,000/US$50,000 in present terms), which allowed her to live comfortably and to pursue her career.

Crimean War

Florence Nightingale's most famous contribution came during the Crimean War, which became her central focus when reports began to filter back to Britain about the horrific conditions for the wounded. On 21 October 1854, she and a staff of 38 women volunteer nurses, trained by Nightingale and including her aunt Mai Smith,[6] were sent (under the authorisation of Sidney Herbert) to Ottoman Empire, about 295 nautical miles (546 km; 339 mi) across the Black Sea from Balaklava in the Crimea, where the main British camp was based.

Nightingale arrived early in November 1854 at Selimiye Barracks in Scutari (modern-day Üsküdar in Istanbul). She and her nurses found wounded soldiers being badly cared for by overworked medical staff in the face of official indifference. Medicines were in short supply, hygiene was being neglected, and mass infections were common, many of them fatal. There was no equipment to process food for the patients.

Until recently it was commonly asserted that Nightingale reduced the death rate from 42% to 2% either by making improvements in hygiene herself or by calling for the Sanitary Commission. For example the 1911 first edition of the Dictionary of National Biography made this claim, but the second edition in 2001 did not. However, death rates did not drop; on the contrary, they began to rise. The death count was the highest of all hospitals in the region. During her first winter at Scutari, 4,077 soldiers died there. Ten times more soldiers died from illnesses such as typhus, typhoid, cholera and dysentery than from battle wounds. Conditions at the temporary barracks hospital were so fatal to the patients because of overcrowding and the hospital's defective sewers and lack of ventilation. A Sanitary Commission had to be sent out by the British government to Scutari in March 1855, almost six months after Florence Nightingale had arrived, and effected flushing out the sewers and improvements to ventilation.[7] Death rates were sharply reduced. During the war she did not recognise hygiene as the predominant cause of death, and she never claimed credit for helping to reduce the death rate.[8]

Nightingale continued believing the death rates were due to poor nutrition and supplies and overworking of the soldiers. It was not until after she returned to Britain and began collecting evidence before the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army that she came to believe that most of the soldiers at the hospital were killed by poor living conditions. This experience influenced her later career, when she advocated sanitary living conditions as of great importance. Consequently, she reduced deaths in the army during peacetime and turned attention to the sanitary design of hospitals.

The Lady with the Lamp

During the Crimean campaign, Florence Nightingale gained the nickname "The Lady with the Lamp", deriving from a phrase in a report in The Times:

She is a ‘ministering angel’ without any exaggeration in these hospitals, and as her slender form glides quietly along each corridor, every poor fellow's face softens with gratitude at the sight of her. When all the medical officers have retired for the night and silence and darkness have settled down upon those miles of prostrate sick, she may be observed alone, with a little lamp in her hand, making her solitary rounds.[9]

The phrase was further popularised by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 1857 poem "Santa Filomena":[10]

Lo! in that house of misery

A lady with a lamp I see

Pass through the glimmering gloom,

And flit from room to room.

Later career

While she was in the Crimea, on 29 November 1855, a public meeting to give recognition to Florence Nightingale for her work in the war led to the establishment of the Nightingale Fund for the training of nurses. There was an outpouring of generous donations. Sidney Herbert served as honorary secretary of the fund, and the Duke of Cambridge was chairman. Nightingale was considered a pioneer in the concept of medical tourism as well, on the basis of her letters from 1856 in which she wrote of spas in Ottoman Empire, detailing the health conditions, physical descriptions, dietary information, and other vitally important details of patients whom she directed there (where treatment was significantly less expensive than in Switzerland). It may be assumed [citation needed] she was directing patients of meagre means to affordable treatment.

By 1859 Nightingale had £45,000 at her disposal from the Nightingale Fund to set up the Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas' Hospital on 9 July 1860. (It is now called the Florence Nightingale School of Nursing and Midwifery and is part of King's College London.) The first trained Nightingale nurses began work on 16 May 1865 at the Liverpool Workhouse Infirmary. She also campaigned and raised funds for the Royal Buckinghamshire Hospital in Aylesbury, near her family home.

Nightingale wrote Notes on Nursing, which was published in 1859, a slim 136-page book that served as the cornerstone of the curriculum at the Nightingale School and other nursing schools established, though it was written specifically for the education of those nursing at home. Nightingale wrote "Every day sanitary knowledge, or the knowledge of nursing, or in other words, of how to put the constitution in such a state as that it will have no disease, or that it can recover from disease, takes a higher place. It is recognised as the knowledge which every one ought to have-distinct from medical knowledge, which only a profession can have".[11]

Notes on Nursing also sold well to the general reading public and is considered a classic introduction to nursing. Nightingale spent the rest of her life promoting the establishment and development of the nursing profession and organizing it into its modern form. In the introduction to the 1974 edition, Joan Quixley of the Nightingale School of Nursing wrote: "The book was the first of its kind ever to be written. It appeared at a time when the simple rules of health were only beginning to be known, when its topics were of vital importance not only for the well-being and recovery of patients, when hospitals were riddled with infection, when nurses were still mainly regarded as ignorant, uneducated persons. The book has, inevitably, its place in the history of nursing, for it was written by the founder of modern nursing".[12]

Nightingale was an advocate for the improvement of care and conditions in the military and civilian hospitals in Britain. Among her popular books are Notes on Hospitals, which deals with the correlation of sanitary techniques to medical facilities; Notes on Nursing, which was the most valued nursing textbook of the day; Notes on Matters Affecting the Health, Efficiency and Hospital Administration of the British Army.

As Mark Bostridge has recently demonstrated, one of Nightingale's signal achievements was the introduction of trained nurses into the workhouse system in England and Ireland from the 1860s onwards. This meant that sick paupers were no longer being cared for by other, able-bodied paupers, but by properly trained nursing staff. This innovation may be said to herald the establishment of the National Health Service in Britain, forty years after Nightingale's death.