Lynching of Laura and L. D. Nelson: Difference between revisions

→Charley Guthrie and Woody Guthrie: - add clarification |

+Coordinates |

||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

{{Lynching in the United States}} |

{{Lynching in the United States}} |

||

{{Coord|35|25|46|N|96|24|28|W|format=dms|display=title|type:event_region:US-OK}} |

|||

{{coord missing|Oklahoma}} |

|||

[[Category:1911 in Oklahoma]] |

[[Category:1911 in Oklahoma]] |

||

Revision as of 01:29, 2 December 2012

| Lynching of Laura and Lawrence Nelson | |

|---|---|

Hundreds gathered on the bridge to look at the bodies. | |

| Date | May 25, 1911 |

| Location | West of Okemah, Oklahoma, on the bridge carrying what is now State Highway 56 across the North Canadian River |

| Photographer | George H. Farnum |

| Charges | None |

Laura and Lawrence Nelson were African Americans who were lynched in Okemah, Oklahoma, on May 25, 1911.[1]

Laura, her husband and their 15-year-old son Lawrence (and their baby, according to some accounts) were taken into custody after Lawrence shot and killed George Loney, Okemah's deputy sheriff. Loney and a posse had arrived at the Nelsons' home to investigate the theft of a cow. Laura's husband pleaded guilty to the theft and was sent to the relative safety of the state prison. In an effort to save her son, Laura said she had fired the fatal shot. Both she and Lawrence were arrested; the son was taken to the local jail and Laura to a cell in the courthouse.[1]

Three weeks later a mob of 40 armed white men arrived to kidnap them, tying up the guard and dragging off the mother and son. Laura was raped, according to some reports, then both were hanged from a bridge over the North Canadian River.[2] Hundreds of sightseers gathered on the bridge the following morning, and photographs of the hanging bodies were sold as postcards. The killers were never identified.[1] The event was later commemorated in a number of songs by the folk singer Woody Guthrie, whose father attended the lynching.

The Nelsons were among at least 4,743 people lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968, around 3,446 of them black, 73 percent of them in the South.[3]

Shooting and arrests

The Nelsons – Austin, Laura, their son Lawrence and a new baby – were an African-American family who lived in a cabin situated seven miles northeast of Paden, Oklahoma. According to a subsequent charge sheet, on May 1, 1911, Austin Nelson stole a cow from Paden resident Claude Littrell.[4] The following day, Deputy Sheriff George Loney and three other police officers visited the Nelsons' property in seach of the missing cow. They found butchered remains in a barn behind the Nelsons' cabin.[5]

When they entered the cabin to question the family, Laura picked up a Winchester rifle. Her son, Lawrence, took the rifle from his mother and fired a single shot. It went through the legs of one officer's pants, then struck Loney in the leg. The officers left the cabin, leaving the severely injured Loney lying in the Nelsons' yard, and began a gun battle with Laura's husband that ended when he ran out of ammunition. By the time the shooting ended, Loney had bled to death, with one report saying that he died begging for water.[5]

The family was arrested and taken to the county jail in Okemah. Austin Nelson was charged and pleaded guilty to cattle rustling. He was sentenced to two years' imprisonment, then sent to the state prison at McAlester, Oklahoma, which probably saved his life. Lawrence remained in Okemah jail, and Laura was placed in a cell in the courthouse, possibly with her nursing baby.[5]

Lynching

Kidnap and killing

During the night of May 25, a mob of 40 armed men arrived at the jail and managed to enter easily through the door, though it was usually locked. They forced the guard, W.D. Payne, to hand over the boy, "about fourteen years old, slender and tall, yellow and ignorant," according to the Okemah Ledger. They also seized Laura, described by the Ledger as "very small of stature, very black, about thirty-five years old, and vicious."[1] According to a black woman who saw the incident, Laura's baby was left behind: "those men just walked off and left that baby lying there. One of my neighbors was there, and she picked the baby up and brought it to town, and we took care of it."[6]

The guard was tied to one of the doors but was able to free himself and call for help an hour later after gnawing through the rope. Sheriff J. A. Dunnegan sent out a search party after the prisoners. By this time, it was too late for the Nelsons.[7] Laura and Lawrence were taken six miles to Yarbrough's Crossing on the North Canadian River to the west of Okemah. There they were gagged with tow sacks and hanged from a bridge on the road to Schoolton.[8]

On its front page The Okemah Ledger called the lynching a masterpiece of planning "executed with silent precision," and in describing the couple wrote: "The woman's arms were swinging by her side, untied, while about 20 feet away swung the boy with his clothes partly torn off and his hands tied with a saddle string ... Gently swaying in the wind, the ghastly spectacle was discovered by a Negro cowboy taking his cow to water. Hundreds of people from Okemah and the western part of the country went to view the scene." It ended the article with: "While the general sentiment is adverse to the method, it is generally thought that the Negroes got what would have been due them under process of law."[9]

According to the Okemah jail guard, W.D. Payne, relatives of the Nelsons refused to claim the bodies. They were buried by the Okfuskee County authorities in a cemetery in Greenleaf, near Okemah.[7]

Photographs and postcards

The scene after the lynching was recorded in a series of photographs by George H. Farnum, the owner of Okemah's only photography studio. He took several pictures from a boat, showing 58 onlookers on the bridge – including six women and 17 children – with the two bodies hanging below. He also took close-ups of the bodies, and as was common practice with lynching photographs, the images were turned into postcards and sold in local stores as souvenirs.[9] J.R. Moehringer writes that they were as common as postcards of Niagara Falls, and when the U.S. Postal Service banned the sending of lynching images in 1908, the cards still sold well door to door.[10] Farnum's photograph of the Nelsons hanging from the bridge was also published in the Ledger, Okemah's local newspaper.[11]

Atlanta antique collector James Allen, who spent years looking for such postcards to publish in his Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America (2000), was offered one of Laura for $75 in a flea market, "caught so pitiful and tattered and beyond retrieving – like a paper kite sagged on a utility wire." As a gay man and the victim of prejudice from other men, Allen identified with the victims. He writes that the photographs engendered in him a "caution of whites, of the majority, of the young, of religion, of the accepted."[10]

Allen argues that the photographers were more than passive spectators; they positioned and lit the corpses as if they were game birds, and the postcards became an important part of the ritual, emphasizing the political nature of the act. Seth Archer writes in the Southwest Review that they were partly intended as a warning, in this case to the neighboring all-black Boley – "look what we did here, Negroes beware" – but the practice of sending the cards to family and friends outside the area underlined the ritualistic nature of the lynchings, death as a community exhibit. Archer compares them to the images from Abu Ghraib prison in 2004, where U.S. service personnel were photographed humiliating their Iraqi prisoners. That lynchings are now viewed with horror in the United States is in part because white Americans came to see black Americans as human, though Archer writes that if the lynchers saw their victims as less human than themselves, "what could members of a lynch mob possibly picture black people to be, if they were less human than the mob that lynched them?"[9]

Reaction

Legal and political

Blacks in Oklahoma and elsewhere expressed outrage at the killings. One black journal lamented:

"Oh! where is that christian spirit we hear so much about

—What will the good citizens do to apprehend these mobs

—Wait, we shall see—Comment is unnecessary. Such a crime is simply

Hell on Earth. No excuse can be set forth to justify the act.[12]

Residents of the black town of Boley were so angry that they talked about organizing a posse to march on Okemah. The rumors sparked a panic among local whites, who sent their women and children away for fear of a retaliatory attack.[13] The lynching was widely reported outside Oklahoma. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) published an exposé of the killings in its magazine The Crisis, in which it highlighted the gruesome photographs taken of the bodies and the egregious circumstances of a mother being killed while protecting her son. The NAACP's chairman, Oswald Garrison Villard, wrote in protest to the governor of Oklahoma, Lee Cruce, about "the horror of the action," and called on the state to bring the killers to justice. In a reply to the NAACP, Cruce assured them he would do everything he could, but defended the laws of Oklahoma as "adequate" and its "juries competent, and except in cases of extreme passion, which no law and no civilization can control."[14] He added:

There is a race prejudice that exists between the white and Negro races wherever the Negroes are found in large numbers. ... Just this week the announcement comes as a shock to the people of Oklahoma that the Secretary of the Interior ... has appointed a Negro from Kansas to come to Oklahoma and take charge of the supervision of the Indian schools of this State. There is no race of people on earth that has more antipathy for the Negro race than the Indian race, and yet these people, numbering many of the best citizens of this State and nation, are to be humbled and their prejudices and passions are to be increased by having this outrage imposed upon them ... If your organization would interest itself to the extent of seeing that such outrages as this are not perpetrated against our people, there would be fewer lynchings in the South than at this time ...[15]

District Judge John Caruthers convened a grand jury in June 1911 to investigate, although no witnesses would identify the 40 men who had taken part. He told the jury:

The people of the state have said by recently adopted constitutional provision that the race to which the unfortunate victims belonged should in large measure be divorced from participation in our political contests, because of their known racial inferiority and their dependent credulity, which very characteristic made them the mere tool of the designing and cunning. It is well known that I heartily concur in this constitutional provision of the people's will. The more then does the duty devolve upon us of a superior race and of greater intelligence to protect this weaker race from unjustifiable and lawless attacks.[1]

No charges were ever brought over the killings. The NAACP argued that nothing had been done to bring the perpetrators to account, and that nothing would change while governors like Cruce sought to excuse lynching as the product of the "uncontrollable passion" of white people to exact what they perceived as justice.[14]

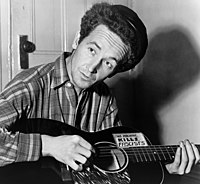

Charley Guthrie and Woody Guthrie

Among those associated with the lynching was Charley Guthrie, a real estate broker and local Democratic politician,[9] and father of the folk singer Woody Guthrie who was born a year later. It remains unclear whether Charley Guthrie was an observer or active participant. According to his son, he became an enthusiastic member of the Ku Klux Klan, which was revived in 1915 after a period of abeyance and became powerful in Oklahoma and the Midwest into the early 1920s.[11]

Woody Guthrie wrote three songs about the lynching: "High Balladree," "Bloody Poll Tax Chain," and "Don't Kill My Baby and My Son" (also called "Old Dark Town" and "Old Rock Jail"). The image of the hanging bodies had a lasting effect on Guthrie, who later recalled seeing as a child "the postcard picture they sold in my home town for several years, a-showing you a negro mother, and her two young sons [sic], a-hanging by the neck from a river bridge, and the wild wind a-whistling down the river bottom, and the ropes stretched tight by the weight of their bodies ... stretched tight like a big fiddle string." In 1946 he alluded to the killings in a sketch, now held by the Ralph Rinzler Archives, depicting a stylized bridge from which dozens of lynched bodies hang, with the crumbling buildings of a decayed city in the background.[11] The folk singer Joel Rafael has composed and recorded his setting of Woody Guthrie lyrics for "Don't Kill My Baby and My Son".

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Davidson 2007, p. 5ff; Allen and Lewis 2000, p. 179.

- ^ Feimster 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 42.

- Amy Louise Wood (2009, p. 4) writes that precise figures are difficult to ascertain, in part because of disagreement about what constitutes a lynching. Several groups have kept records, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Tuskegee Institute, and the Chicago Tribune, but researchers believe that many rural lynchings were not recorded. Wood estimates that 3,200 black men were lynched in the South between 1880 and 1940.

- ^ The State of Oklahoma, Plaintiff, vs Austin Nelson, Defendant. May 1911

- ^ a b c Owens 2000, pp. 132–133. * That he died begging for water, see Klein 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Reese 1997, p. 179.

- For two brief contemporaneous reports of the lynching, see Clinton Mirror, May 27, 1911, and The Dispatch, June 7, 1911.

- ^ a b McMahan 1945.

- ^ The Crisis, July 1911, cited in The National Association of Colored People, 1919; and in Kennedy 1998, p. 44.

- For the gagging, see Allen and Lewis 2000, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Archer, September 22, 2006.

- ^ a b Allen and Lewis 2000, p. 204.

- For an interview with Allen, see Moehringer, August 27, 2000.

- For more about the postcards and their banning by the U.S. Postal Service, see Gonzales 2006.

- ^ a b c Jackson 2008, pp. 136, 156–158.

- ^ Shepard 2009, pp. 166–167.

- ^ Klein 1999, p. 10.

- ^ a b Williams 2012, pp. 193–194.

- ^ The Crisis, August 1911, pp. 153–154.

References

- Allen, James and Lewis, Jon. Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America. Twin Palms Publishers, 2000.

- Archer, Seth. "Reading the Riot Acts", Southwest Review, September 22, 2006.

- Clinton Mirror. "Mother and son lynched", May 27, 1911.

- Davidson, James West. 'They say': Ida B. Wells and the Reconstruction of Race. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Feimster, Crystal. Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Gonzales, Rita. "With non [sic but the omnipresent stars to witness": review of Ken Gonzales-Day's Hang Trees], Pomona College Museum of Art, 2006.

- Jackson, Mark Allan. Prophet Singer: The Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie. University Press of Mississippi, 2008.

- Kennedy, Randall. Race, Crime, and the Law. Vintage Books, 1998.

- Klein, Joe. Woody Guthrie: A Life. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1999.

- McMahan, Hazel Ruby. "Stories of Early Oklahoma", State Historian for Oklahoma Society Daughters of American Revolution, 1945 (copy at Oklahoma Historical Society Library, call number F/699/S7).

- Moehringer, J.R. "An Obsessive Quest to Make People See", The Los Angeles Times, August 27, 2000.

- Owens, Ron. Oklahoma heroes: the Oklahoma Peace Officers Memorial. Turner Publishing Company, 2000.

- Reese, Linda Williams. Women of Oklahoma, 1890-1920. University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

- Shepard, R. Bruce. "Diplomatic Racism: Canadian Government and Black Migration from Oklahoma, 1905-1912," in Glasrud, Bruce A. and Braithwaite, Charles A. (eds.). African Americans on the Great Plains: An Anthology. University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- The Dispatch. "News from everywhere", June 7, 1911.

- The National Association of Colored People. "The Story of One Hundred Lynchings," 1919.

- The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. "The Oklahoma Lynching", The Crisis, Vol. 2, number 4, August 1911.

- Williams, Kidada. They Left Great Marks on Me: African American Testimonies of Racial Violence from Emancipation to World War I. NYU Press, 2012.

- Wood, Amy Louise. Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940. University of North Carolina Press Books, 2009.

Further reading

- James Allen, "Without Sanctuary", a brief film about his collection

- Apel, Dora, and Smith, Shawn Michelle. Lynching Photographs. University of California Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-520-25152-6

- Guthrie, Woody. Don't Kill My Baby and My Son. 1966; also see "Don’t Kill My Baby and My Son", YouTube.