Enlargement of the eurozone: Difference between revisions

Danlaycock (talk | contribs) rewrite criteria on ERM II. This is just a rough outline, so we probably don't need to get into all the caveats here. |

→Sweden: EC has approved that Sweden adopt a "waiting position" until a prior referendum approval can be reached |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

According to the 1994 accession treaty,<ref>{{Cite web| url=http://www.consilium.europa.eu/cms3_Applications/applications/Accords/details.asp?cmsid=297&id=1994028&lang=EN&doclang=EN | title=European Union Agreement Details | publisher=Council of the European Union | accessdate=26 December 2008}}</ref> approved by referendum (52% in favour of the treaty), Sweden is required to join the euro if, at some point, the convergence criteria are fulfilled. However, on 14 September 2003 56% of Swedes voted against adopting the euro in a second [[Referendums in Sweden|referendum]].<ref>{{Cite web| url=http://www.val.se/val/emu2003/resultat/slutresultat/ | title=Folkomröstning 14 september 2003 om införande av euron | language=Swedish | accessdate=2 February 2008 | publisher=[[Swedish Election Authority]]}}</ref> The Swedish government has argued that staying outside the euro is legal since one of the requirements for eurozone membership is a prior two-year membership of the [[ERM II]]; by simply choosing to stay outside the exchange rate mechanism, the Swedish government is provided a formal loophole avoiding the requirement of adopting the euro. Most of Sweden's major parties continue to believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum for the time being and show no interest in raising the issue. |

According to the 1994 accession treaty,<ref>{{Cite web| url=http://www.consilium.europa.eu/cms3_Applications/applications/Accords/details.asp?cmsid=297&id=1994028&lang=EN&doclang=EN | title=European Union Agreement Details | publisher=Council of the European Union | accessdate=26 December 2008}}</ref> approved by referendum (52% in favour of the treaty), Sweden is required to join the euro if, at some point, the convergence criteria are fulfilled. However, on 14 September 2003 56% of Swedes voted against adopting the euro in a second [[Referendums in Sweden|referendum]].<ref>{{Cite web| url=http://www.val.se/val/emu2003/resultat/slutresultat/ | title=Folkomröstning 14 september 2003 om införande av euron | language=Swedish | accessdate=2 February 2008 | publisher=[[Swedish Election Authority]]}}</ref> The Swedish government has argued that staying outside the euro is legal since one of the requirements for eurozone membership is a prior two-year membership of the [[ERM II]]; by simply choosing to stay outside the exchange rate mechanism, the Swedish government is provided a formal loophole avoiding the requirement of adopting the euro. Most of Sweden's major parties continue to believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum for the time being and show no interest in raising the issue. |

||

The parties seem to agree that Sweden would not adopt the euro until after a second referendum. Prime Minister [[Fredrik Reinfeldt]] stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.<ref name=aftonbladetreinfeldt>{{Cite web|url=http://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/article1377536.ab |title= Glöm euron, Reinfeldt| publisher=[[Aftonbladet]] | date=2 December 2007 | accessdate=3 February 2008 | language=Swedish}}</ref> The |

The parties seem to agree that Sweden would not adopt the euro until after a second referendum. Prime Minister [[Fredrik Reinfeldt]] stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.<ref name=aftonbladetreinfeldt>{{Cite web|url=http://www.aftonbladet.se/nyheter/article1377536.ab |title= Glöm euron, Reinfeldt| publisher=[[Aftonbladet]] | date=2 December 2007 | accessdate=3 February 2008 | language=Swedish}}</ref> The European Commission, represented by [[Olli Rehn]], has confirmed they accept Sweden wont adopt the euro before a prior referendum approval.<ref name="EC approved Swedish euro referendum">{{cite web |url = http://www.europarl.europa.eu/hearings//press_service/product.htm?ref=20100108IPR66990&language=EN |title = Summary of hearing of Olli Rehn – Economic and Monetary Affairs (Hearings - Institutions - 12-01-2010 - 09:39) |date = 11 January 2101 |publisher = [[European Parliament]] |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20120118074039/http://www.europarl.europa.eu/hearings/press_service/product.htm?ref=20100108IPR66990&language=EN |archivedate=18 January 2012 |accessdate = 11 May 2013 |quote =Olle Schmidt (ALDE, SE) inquired whether Sweden could still stay out of the Eurozone. Mr Rehn replied that it is up to the Swedish people to decide on the issue. |ref = }}</ref> This position is offered solely to Sweden, while the Commission has prohibited euro adoption referendums to be held in the new member states accessing EU in 2004 and later. |

||

The polls have generally showed stable support for the "no" alternative, except some polls in 2009 showing a support for "yes". From 2010 to 2013 the polls showed strong support for "no" again. |

|||

==States not obliged to join== |

==States not obliged to join== |

||

| Line 177: | Line 179: | ||

!ERM II<br>entry |

!ERM II<br>entry |

||

!Coordinating institution |

!Coordinating institution |

||

!Changeover plan |

!Changeover plan<br><small>(latest version)</small> |

||

!Introduction<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/adoption/scenarios/index_en.htm|publisher=http://ec.europa.eu/|accessdate=7 September 2013|title=Scenarios for adopting the euro}}</ref> |

!Introduction<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/euro/adoption/scenarios/index_en.htm|publisher=http://ec.europa.eu/|accessdate=7 September 2013|title=Scenarios for adopting the euro}}</ref> |

||

!Dual circulation<br> period |

!Dual circulation<br> period |

||

| Line 226: | Line 228: | ||

|----- bgcolor="#ececec" |

|----- bgcolor="#ececec" |

||

|{{DEN}} |

|{{DEN}} |

||

|Opt-out<br><small>(A [[Danish European Union opt-outs referendum|referendum]] is planned for after the [[Next Danish general election|next general election]])</small> |

|<span style="display:none">Opt-out formal, with current abrogation consideration</span>Opt-out<br><small>(A [[Danish European Union opt-outs referendum|referendum]] is planned for after the [[Next Danish general election|next general election]])</small> |

||

|<span style="display:none">1999-01-01</span>'''1 January 1999''' |

|<span style="display:none">1999-01-01</span>'''1 January 1999''' |

||

| – |

| – |

||

| Line 242: | Line 244: | ||

|Not set |

|Not set |

||

|<small>''National Euro Coordination Committee''<br>(established Sep.2007)</small> |

|<small>''National Euro Coordination Committee''<br>(established Sep.2007)</small> |

||

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved Nov.2009)<ref>http://www.mnb.hu/MNBEuro_Index/ |

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved Nov.2009)<ref>http://www.mnb.hu/Root/Dokumentumtar/MNB/MNBEuro_Index/A_jegybank/euro_main_1/nat_2009_hu_vegleges.pdf</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.euo.dk/upload/application/pdf/b8685355/Ungarneurochangeover.pdf%3Fdownload%3D1|title=National Changeover Plan for Hungary|format=PDF|publisher=Magyar Nemzeti Bank|date=12 December 2008}}</ref></small> |

||

|Big-Bang |

|Big-Bang |

||

|less than<br>1 month<br><small>(not decided yet)</small> |

|less than<br>1 month<br><small>(not decided yet)</small> |

||

| Line 255: | Line 257: | ||

|<span style="display:none">2004-06-28</span>'''28 June 2004''' |

|<span style="display:none">2004-06-28</span>'''28 June 2004''' |

||

|<small>''Commission for the Coordination of the Adoption of the euro in Lithuania''<br>(established Feb.2013)</small> |

|<small>''Commission for the Coordination of the Adoption of the euro in Lithuania''<br>(established Feb.2013)</small> |

||

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved Jun.2013)<ref>http://www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter3/dokpaieska.showdoc_l?p_id=453080&p_query=&p_tr2=2</ref><br>'''Changeover law'''<br>(passed |

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved Jun.2013)<ref>http://www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter3/dokpaieska.showdoc_l?p_id=453080&p_query=&p_tr2=2</ref><br>'''Changeover law'''<br>(passed Apr.2014)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.baltictimes.com/news/articles/34786/|title= Lithuania readies for euro adoption|date=1 May 2014|accessdate=2014-05-01|publisher=BalticTimes.com}}</ref></small> |

||

|Big-Bang |

|Big-Bang |

||

|15 days |

|15 days |

||

|<small>'''Banks:'''<br>6 months<br>'''Central bank:'''<br> |

|<small>'''Banks:'''<br>6 months<br>'''Central bank:'''<br>infinity</small> |

||

|<small>Start 30 days after [[Council of the European Union|Council]] approval of euro adoption, equal to 22 Aug.2015, and lasts until 12 months after adoption</small> |

|<small>Start 30 days after [[Council of the European Union|Council]] approval of euro adoption, equal to 22 Aug.2015, and lasts until 12 months after adoption</small> |

||

|[[Lithuanian Mint|Yes]]<ref name="Lithuanian euro coins"/> |

|[[Lithuanian Mint|Yes]]<ref name="Lithuanian euro coins"/> |

||

| Line 268: | Line 270: | ||

|Not set |

|Not set |

||

|<small>''The Government Plenipotentiary for the Euro Adoption in Poland'', and ''National Coordination Committee for Euro Changeover'', and ''Coordinating Council''<br>(all established Nov.2009)</small> |

|<small>''The Government Plenipotentiary for the Euro Adoption in Poland'', and ''National Coordination Committee for Euro Changeover'', and ''Coordinating Council''<br>(all established Nov.2009)</small> |

||

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved in 2011, but an updated plan is under preparation){{Non-euro_currencies_of_the_European_Union/RefTag|1='''Cite from the 2014 Polish convergence report:''' ''Due to the significant reform agenda in the European Union and in the euro area, the current objective is to update the National Euro Changeover Plan with reference to the impact of those changes on Poland’s euro adoption strategy. The date of completion of the document is conditional on the adoption of binding solutions on the EU forum concerning the key institutional changes, in particular, those referring to the banking union. The outcome of these changes determines the area of the necessary institutional and legal adjustments as well as the national balance of costs and benefits arising from introduction of the common currency.''<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/pdf/csr2014/cp2014_poland_en.pdf|title=Convergence programme: 2014 update|publisher=Republic of Poland|format=PDF|date=April 2014}}</ref>|name=Poland|group="nb"}}</small> |

|||

|<small>Changeover plan<br>(approved in 2011, but an updated plan is under preparation)</small> |

|||

| – |

| – |

||

| – |

| – |

||

| Line 289: | Line 291: | ||

|[[Romania and the euro|Not yet<br/>decided]] |

|[[Romania and the euro|Not yet<br/>decided]] |

||

| – |

| – |

||

|----- |

|----- bgcolor="#ececec" |

||

|{{SWE}} |

|{{SWE}} |

||

| |

|<span style="display:none">Opt-out de facto</span>''De facto opt-out''{{Non-euro_currencies_of_the_European_Union/RefTag|name=Sweden|group="nb"}}<br><small>(The Swedish government has made joining the euro subject to approval by a referendum)</small> |

||

|Not under consideration<br><small>(The [[Sveriges Riksbank|Swedish National Bank]]'s monetary policy is to not peg the SEK to the euro as long as there is no referendum approving euro adoption)</small> |

|Not under consideration<br><small>(The [[Sveriges Riksbank|Swedish National Bank]]'s monetary policy is to not peg the SEK to the euro as long as there is no referendum approving euro adoption)</small> |

||

| – |

| – |

||

| Line 304: | Line 306: | ||

|----- bgcolor="#ececec" |

|----- bgcolor="#ececec" |

||

|{{GBR}} |

|{{GBR}} |

||

|<span style="display:none">Opt-out formal</span>Opt-out |

|||

|Opt-out |

|||

|Not under consideration |

|Not under consideration |

||

| – |

| – |

||

Revision as of 19:15, 22 August 2014

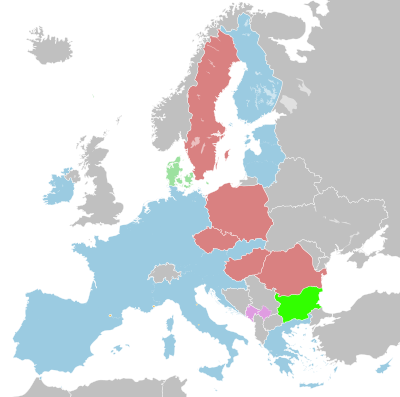

The enlargement of the eurozone is an ongoing process within the European Union (EU). All Member states of the European Union, except for Denmark and the United Kingdom are obliged to adopt the euro as their sole currency once they meet the criteria, including: complying with the debt and deficit criteria outlined by the Stability and Growth Pact, keeping inflation and long-term governmental interest rates below certain reference values, stabilizing their currency's exchange rate versus the euro by participating in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II), and ensuring that their national laws comply with the ECB statute, ESCB statute and articles 130+131 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The obligation to adopt the euro is outlined by the accession treaties, and the European Commission decided in 2004 not to allow for any more separate euro adoption referendums to take place, except for the three countries (UK, Denmark and Sweden) previously having negotiated such a process as a prerequisite for euro adoption.

The eurozone currently comprise 18 EU states, of which the first 11 (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain) introduced the euro 1 January 1999 when it was electronic only. Greece joined 1 January 2001, one year before the physical euro coins and notes replaced the old national currencies in the eurozone. Subsequently, the following six countries also joined the eurozone on 1 January in the mentioned year: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009),[1] Estonia (2011)[2] and Latvia (2014).[3]

Lithuania has been approved for euro adoption on 1 January 2015.[4] Seven remaining states are on the enlargement agenda: Romania, Bulgaria, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Sweden and Croatia. Denmark is not obliged to join, but a referendum on the renunciation of their EU opt-outs is proposed to be held during the next parliamentary term between 2015 and 2019, though this referendum may not include membership of the EMU. Should the country decide to do so, it may join the eurozone rapidly as Denmark is already part of the ERM-II. The United Kingdom has opted to stay outside of the EMU, and currently has no intention of adopting the euro.

Accession criteria

In order for a state to formally join the eurozone, enabling them to mint euro coins and get a seat at the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Eurogroup, a country must be a member of the European Union and comply with five convergence criteria, which were initially defined by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. These criteria include: complying with the debt and deficit criteria outlined by the Stability and Growth Pact, keeping inflation and long-term governmental interest rates below reference values, and stabilizing their currency's exchange rate versus the euro by participating in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). The country must also ensure that their national laws are compliant with the ECB statute, ESCB statute and articles 130+131 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. The obligation for all EU member states to adopt the euro is outlined by their accession treaty, and the European Commission decided in 2004 not to allow for any more euro adoption referendums, with the exception of the three countries (UK, Denmark and Sweden) which had previously negotiated such a process as a prerequisite for their adoption of the euro.

The European microstates of Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican City, which had a monetary agreement with a eurozone state when the euro was introduced, were granted a special permission to continue these agreements and to issue separate euro coins, but they don't get any input or observer status in the economic affairs of the eurozone. Andorra, which has used the euro unofficially since the inception of the currency, negotiated a similar agreement which granted them the right to officially use the euro as of 1 April 2012 and to issue euro coins.[5] Andorra is expected to issue their first coins in early 2014.[6]

In 2009 the authors of a confidential International Monetary Fund (IMF) report suggested that in light of the ongoing global financial crisis, the EU Council should consider granting new EU member states which are having difficulty complying with all five convergence criteria the option to "partially adopt" the euro, along the lines of the monetary agreements signed with the European microstates outside the EU. These states would gain the right to adopt the euro and issue a national variant of euro coins, but would not get a seat in ECB or the Eurogroup until they met all the convergence criteria.[7] However, the EU has not made use of this alternative accession process.

| Country | HICP inflation rate[8][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[9] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[10][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[11] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[12] | ERM II member[13] | Change in rate[14][15][nb 3] | ||||

| Reference values[nb 4] | Max. 3.3%[nb 5] (as of May 2024) |

None open (as of 19 June 2024) | Min. 2 years (as of 19 June 2024) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2023) |

Max. 4.8%[nb 5] (as of May 2024) |

Yes[16][17] (as of 27 March 2024) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2023)[16] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2023)[16] | ||||||

| 5.1% | None | 3 years, 11 months | 0.0% | 4.0% | Yes | ||

| 1.9% | 23.1% | ||||||

| 6.3% | None | No | 2.3% | 4.2% | No | ||

| 3.7% (exempt) | 44.0% | ||||||

| 1.1% | None | 25 years, 5 months | 0.2% | 2.6% | Unknown | ||

| -2.3% (surplus) | 36.7% | ||||||

| 8.4% | None | No | 2.4% | 6.8% | No | ||

| 6.7% | 73.5% | ||||||

| 6.1% | None | No | 3.1% | 5.6% | No | ||

| 5.1% | 49.6% | ||||||

| 7.6% | Open | No | -0.3% | 6.4% | No | ||

| 6.6% | 48.8% | ||||||

| 3.6% | None | No | -8.0% | 2.5% | No | ||

| 0.6% | 31.2% | ||||||

- Notes

- ^ The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- ^ The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not to be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- ^ The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- ^ Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2024.[16]

- ^ a b Belgium, Denmark, and the Netherlands were the reference states.[16]

- ^ The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

Reference values in 2013

The reference values fixing the upper limit for HICP inflation and long term interest rates for acceding states are recalculated at the end of each month using the yearly average for the three EU Member States with the lowest HICP figures (ignoring states classified as "outliers"). Based on the latest Economic Forecast report from the European Commission, the table below lists the three benchmark countries and their forecast HICP, along with the resulting HICP reference value, for the end of all four quarters in 2013.[21] As no official forecast exists for "Long term interest rates", these reference values have not been forecast in advance. The table also lists the final reference values measured by Eurostat at the end of each month.

Template:ECB reference values The national fiscal accounts for the previous full calendar year are released each year in April (next time 30 April 2014).[22] As the compliance check for both the debt and deficit criteria always awaits this release in a new calendar year, the first possible month to request a compliance check will be April, which would result in a data check for the HICP and Interest rates during the reference year from 1 April to 31 March. Any EU Member State may also ask the ECB for a compliance check, at any point of time during the remainder of the year, with HICP and interest rates always checked for the past 12 months – while debt and deficit compliance will be checked for the latest full calendar year.[23]

Historical enlargements

The first enlargement, to Greece, took place on 1 January 2001, before the euro had physically entered into circulation in 2002, but after its formal creation in 1999. The next enlargements were to states which joined the EU in 2004. First Slovenia, replacing the Slovenian tolar on 1 January 2007, then Cyprus and Malta on 1 January 2008. On 1 January 2009 Slovakia exchanged its koruna for the euro, on 1 January 2011 Estonia similarly exchanged its kroon for the euro, and most recently Latvia replaced the lats with the euro on 1 January 2014.

The new EU members which joined the bloc during the fifth enlargement wave (2004–2007) are all obliged to adopt the euro under the terms of their accession treaties, however, in September 2011 Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania said the eurozone they thought they were going to join, a monetary union, may very well end up being a very different union entailing much closer fiscal, economic and political convergence. "All seven countries agree to state that a change in the euro zone's legal status could change the conditions of their adhesion treaties," which "could force them to stage new referenda" on euro take-up, said a diplomatic source close to the talks to AFP.[24]

States obliged to join

- European Union member states (special territories not shown)

- 20 in the eurozone1 in ERM II, with an opt-out (Denmark)5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

Apart from Denmark and the United Kingdom, which have opt-outs under the Maastricht Treaty, all other EU members are legally obliged to join the eurozone.

ERM II members

The following states have acceded to ERM II, in which they must spend two years, before they can adopt the euro.

Lithuania

The Lithuanian litas is part of ERM II and in practice it is pegged to the euro at a rate of 3.45280 litai = €1. Lithuania originally set 1 January 2007 as the target date for joining the euro, but their application was rejected by the European Commission because inflation was slightly higher (0.1%) than the permitted maximum. In December 2006 the government approved a new convergence plan, which put the expected adoption date to post-2010 due to inflation.[25] In 2007, Prime Minister Gediminas Kirkilas hoped for adoption around 2010–11 though inflation was still a problem.[26][27]

By the time of the 2010 European sovereign-debt crisis, the expected date had been put further back to 2014.[28] Lithuania expressed interest in a suggestion from the IMF that countries who aren't able to meet the Maastricht criteria are able to "partially adopt" the euro, using the currency but not getting a seat at the European Central Bank.[29] Interviews with the Foreign Minister and Prime Minister in May and August 2012 respectively highlighted that Lithuania still aimed to, and was able to, join the euro but would not set a date until the state of the eurozone post-crisis was clear.[30][31]

During the 2012 Lithuanian parliamentary election campaign, the Social Democrats were reported to prefer delaying the euro adoption, from the previous 2014 target until 1 January 2015.[32] When the second round of the elections were concluded in October, the Social Democrats and two coalition parties won a majority and formed the new government, and the coalition parties were expected to accept the proposed delay in adoption of the euro.[33] When Prime Minister Algirdas Butkevičius presented his new government in December, eurozone accession as soon as possible was mentioned as one of the key priorities for the government. The Prime Minister said: "January 2015 is a feasible date. But things can also turn out, that we may try to adopt the euro together with Latvia in January 2014. Let the first quarter (of 2013) pass, and we'll give it a thought."[34] However, in January 2013 the PM announced that the government and the Bank of Lithuania had agreed on a 2015 target date.[35] In February 2013, the government approved their plan for euro adoption in 2015.[36]

In January 2014 it was announced that all coins will have "2015" printed on them to display the year of Lithuania's euro adoption. The Lithuanian Mint has been chosen to mint the coins.[37][38] Lithuania's parliament approved a euro changeover law in April 2014,[39] and in their biennial reports released on 4 June the ECB and the European Commission found that the country satisfied the convergence criteria.[40][41][42][43] On 16 July the European Parliament voted in favour of Lithuania adopting the euro.[44][45] On 23 July the EU Council of Ministers approved the decision, clearing the way for Lithuania to adopt the euro on 1 January 2015.[4]

Other states

The following members must first join ERM II before they can adopt the euro:

Bulgaria

The lev is not part of ERM-II, but has been pegged to the euro since its launch (€1 = BGN 1.95583). It was previously pegged on a par to the German Mark. By 2007 Bulgaria already fulfilled the great majority of the EMU membership criteria, and in November 2007 the Finance Minister Plamen Oresharski set a target to join ERM-II early in 2009 so it could comply with all five convergence criteria by April 2011 and adopt the euro on 1 January 2012.[46]

While the currency board which pegs Bulgaria to the euro has been seen as beneficial to the country fulfilling EMU criteria so early,[47] the ECB has been pressuring Bulgaria to drop it as it did not know how to let a country using a currency board join the euro.[clarification needed] The Prime Minister has stated the desire to keep the currency board until the euro was adopted. However, factors such as a high inflation, an unrealistic exchange rate with the euro and the country's low productivity are negatively affected by the system.[48]

Besides not complying with the requirement to be an ERM-II member, Bulgaria also derogated on the price stability criterion in 2007. Bulgaria's inflation in the 12 months from April 2007 to March 2008 reached 9.4%, well above the reference value limit at 3.2%. On the upside, Bulgaria safely met the criteria of only having a deficit at maximum 3% of GDP, as it managed to post a solid surplus in 2007 at 3.4% of GDP. Bulgaria also had no problem to complying with the public debt criteria. During the past decade, the Bulgarian debt declined from 50% of GDP to just 18% in 2007. Finally, the average for the long-term interest rate during the past year was only 4.7% in March 2008, and thus also well within the reference limit at 6.5%.[49]

Bulgaria was expected to enter ERM II in November 2009,[50] but that target date has been moved. On 22 December 2009 Simeon Dyankov, Bulgaria's finance minister, said that the country would apply to join the ERM II in March 2010,[51] but due to a high deficit Bulgaria decided not to apply in 2010.[52] A 2008 analysis said that Bulgaria would not be able to join the Eurozone earlier than 2015, due to the high inflation and the repercussions of the global financial crisis of 2007-2008.[53]

Bulgaria managed in 2011 to comply with four out of five convergence criteria for euro adoption. The only criteria not being met was the requirement to have been a member of ERM-II for a minimum of two years. The Bulgarian Finance Minister Simeon Dyankov explained in July 2011 that the government made the political decision not to apply for ERM-II membership for as long as the European sovereign-debt crisis was still ongoing and unsolved; that would mean that the fifth criteria would be met in 2015 at the earliest, with a subsequent adoption of the euro on 1 January 2016.[54] According to Deutsche Bank, the government had selected a target date for ERM-II entry of the beginning of 2013, which would correspond to euro adoption on 1 January 2016 at the earliest.[55] The government reiterated in September 2012 that they had no intention to join ERM-II or adopt the euro for as long as the eurozone debt crisis remained unsolved. The government still wanted certainty and clarity of all the consequences of adopting the euro before deciding to join.[56]

Croatia

Croatia became a member of the EU on 1 July 2013.[57] Croatia is obliged to eventually adopt the euro. Although in the past Croatia has fulfilled the main euro convergence criteria, it did not in 2013. Prior to Croatian entry to the EU on 1 July 2013, Boris Vujčić, governor of the Croatian National Bank, stated that he would like the kuna to be replaced by the euro as soon as possible after the accession.[58] The European Central Bank expects Croatia to be approved for ERM II membership in 2016 at the earliest, with euro adoption in 2019.[59]

Czech Republic

The Czech Republic is bound by their Treaty of Accession to join the eurozone, but as the Czech koruna is not part of ERM-II, this is not likely to happen soon. Since joining the EU in May 2004, the Czech Republic has adopted fiscal and monetary policies that aims to align its macroeconomic conditions with the rest of the European Union. Originally, the Czech Republic aimed for entry into the ERM II in 2008 or 2009, but due to a mix of economic and political reasons this has been postponed. The European sovereign-debt crisis further decreased the Czech Republic's interest in joining the eurozone,[60] and currently the state has no official target date for euro adoption.[61]

In late 2010 a discussion arose within the Czech government, partially initiated by then President Václav Klaus, a well known Euro-sceptic, over negotiating an opt-out from joining the Eurozone. Czech Prime Minister Petr Nečas later stated that no opt-out was required because the Czech Republic could not be forced to join the ERM II and thus could decide if or when to fulfill one of the necessary criteria to join the Eurozone, an approach similar to that of Sweden. Nečas also stated that his cabinet would not decide upon joining the ERM II during its term, which is due to expire in May 2014.[62][63]

During the European sovereign debt crisis, Nečas said that since the conditions governing the Eurozone had significantly changed since their accession treaty was ratified, he believed that Czechs should be able to decide by a referendum whether to join the Eurozone under the new terms.[64] One of the government's junior coalition parties, TOP09, is opposed to a euro referendum.[65][66] Miloš Zeman, who was elected President of the Czech Republic in early 2013, supports euro adoption by the Czech Republic, though he also advocates for a referendum on the decision.[67][68] Shortly after taking office in March 2013, Zeman suggested that the Czech Republic would not be ready for the switch for at least five years.[69] The leader of the opposition Social Democrats, Bohuslav Sobotka, who in April 2013 held a 30% lead over the current Prime Minister's Civic Democratic Party (ODS) in opinion polls, stated on 25 April 2013 that he was "convinced that the government that will be formed after next year's election should set the euro entry date" and that "1 January 2020 could be a date to look at".[70]

In April 2013, the Czech Ministry of Finance stated in its Convergence Programme delivered to the European Commission that the country had not yet set a target date for euro adoption and would not apply for ERM-II membership in 2013. Their goal was to limit their time as an ERM-II member, prior to acceding to the eurozone, to as brief as possible.[61] In December 2013, the Czech National Bank announced it had agreed with the government not to apply for ERM-II membership in 2014.[71]

Hungary

Hungary originally hoped to adopt the euro by 1 January 2010. Most financial studies, such as those produced by Standard & Poor's and by Fitch Ratings, suggested that Hungary would be unable to adopt the common European currency on schedule, due to the country's high deficit, which in 2006 exceeded 10% of the GDP. The deficit fell below 5% of GDP in 2007, and was expected to be 3.8% at the end of 2008.

In February 2011, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán made clear, that he does not expect the euro to be adopted in Hungary before 1 January 2020. No official target date has been set, but the government has committed itself to comply with all Maastricht criteria in 2018, which would make it possible to adopt the euro on 1 January 2020.[72][73]

Poland

Poland is bound by the Treaty of Accession 2003 to join the euro at some point, but current indications are that this will not be for several years to come as economic criteria must be met. The złoty is not part of ERM II, itself a requirement for euro membership.

The Finance Minister Dominik Radziwill said on 10 July 2009 that Poland could enter the Eurozone in 2014, meeting the fiscal criteria in 2012.[74] In 2010, the eurozone's debt crisis caused Poles' interest to cool, with nearly half of the population opposed to entry.[60] However in December 2011 Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski said that Poland aimed to adopt the euro on 1 January 2016, but only if "the eurozone is reformed by then, and the entrance is beneficial to us."[75] A poll conducted by TNS Polska for the newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza on 10–13 May 2012 showed that support for euro adoption depends on the target date, with 13% in favour of adoption in 2014, 38% which prefer adoption at the earliest in 2015, and 28% that felt that the country should never join the eurozone.[76] According to a recent poll for the German Marshall Fund published in September 2012, 71% of Poles believed that switching to the euro at present time could be bad for the Polish economy.[77]

There is currently no official or binding target date for the Polish euro adoption, and no fixed date for when the country will join ERM-II (the fifth convergence criteria). However, the Polish government plans to be able to comply with all the Euro adoption criteria by 2015.[78] Poland will also need to pass the required domestic laws for the euro adoption, possibly as a constitutional amendment.

In autumn 2012 the Monetary Policy Council of the Polish National Bank published its official monetary guidelines for 2013, confirming earlier political statements that Poland should only join the ERM-II once the existing eurozone countries had overcome the ongoing European sovereign-debt crisis, to maximise the benefits of monetary integration and minimise associated costs.[79]

Romania

Romania is scheduled to replace the current national currency, the Romanian leu, with the euro once Romania fulfills the euro convergence criteria. Originally, the euro was scheduled to be adopted by Romania on 1 January 2015.[80][81] In April 2011, the Romanian government announced it would not be ready to join the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) before 2013–2014, meaning that euro adoption was only likely to happen on 1 January 2016/2017.[82] In April 2012, the Romanian convergence report submitted under the Stability and Growth Pact which still listed 1 January 2015 to be the target date for the aspired euro adoption.[83] The target year in 2015 is however currently no longer possible to achieve, as it would have required Romania to join ERM2 before October 2012. If Romania decides to join ERM2 before October 2013, the country will now instead be headed to comply with the fifth euro-adaption criteria (the demand for minimum 2-years of ERM2-membership) in 2015; meaning that the earliest possible time for Romania to adopt the euro will be on 1 January 2016. Because for statistical reasons any euro-adoption will only happen on the upcoming 1 January, after the exact point of time where the country has been declared "euro ready" by ECB; and for practical reasons minimum 3 months are also needed after approval for Romania+ECB to prepare for the adoption to take place. So that is why 30 September is the ultimately last deadline for compliance, ahead of any targeted 1 January adoption.

The governor of the National Bank of Romania confirmed in November 2012, that Romania would not meet its previous target of joining the eurozone in 2015. He mentioned that it had been a financial benefit for Romania to not be a part of the euro area during the European debt-crisis, but that the country in the years ahead would strive to comply with all the convergence criteria.[84] In April 2013 Romania submitted their annual Convergence Programme to the European Commission, which for the first time did not specify a target date for euro adoption.[85][86] Prime Minister Victor Ponta has stated that "eurozone entry remains a fundamental objective for Romania but we can't enter poorly prepared", and that 2020 was a more realistic target.[86] The following year, Romania's Convergence Report set a target date of 1 January 2019 for euro adoption.[87][88]

Sweden

According to the 1994 accession treaty,[89] approved by referendum (52% in favour of the treaty), Sweden is required to join the euro if, at some point, the convergence criteria are fulfilled. However, on 14 September 2003 56% of Swedes voted against adopting the euro in a second referendum.[90] The Swedish government has argued that staying outside the euro is legal since one of the requirements for eurozone membership is a prior two-year membership of the ERM II; by simply choosing to stay outside the exchange rate mechanism, the Swedish government is provided a formal loophole avoiding the requirement of adopting the euro. Most of Sweden's major parties continue to believe that it would be in the national interest to join, but they have all pledged to abide by the result of the referendum for the time being and show no interest in raising the issue.

The parties seem to agree that Sweden would not adopt the euro until after a second referendum. Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt stated in December 2007 that there will be no referendum until there is stable support in the polls.[91] The European Commission, represented by Olli Rehn, has confirmed they accept Sweden wont adopt the euro before a prior referendum approval.[92] This position is offered solely to Sweden, while the Commission has prohibited euro adoption referendums to be held in the new member states accessing EU in 2004 and later.

The polls have generally showed stable support for the "no" alternative, except some polls in 2009 showing a support for "yes". From 2010 to 2013 the polls showed strong support for "no" again.

States not obliged to join

Denmark

Denmark has pegged its krone to the euro (€1 = DKK 7.46038 ± 2.25%) since 1 January 1999, and the krone remains in the ERM II. In December 1992, Denmark negotiated four opt-out clauses from the Maastricht Treaty via the Edinburgh Agreement, including not adopting the euro as currency. This was done in response to the Maastricht treaty having been rejected by the Danish people in a referendum earlier that year. As a result of the changes, the treaty was finally ratified in a subsequent referendum held in 1993. On 28 September 2000, a euro referendum was held in Denmark resulting in a 53.2% vote against the government's proposal to abrogate the euro opt-out.

On 22 November 2007, the newly re-elected Danish government declared its intention to hold a new referendum on the abolition of all four opt-out clauses, including on the euro, by 2011.[93] Several polls have been done each year; in 2008 and 2009 they generally, but did not always, showed support among Danes for adopting the euro. Due to increased uncertainty, both in terms of the stability of the euro and the establishment of new political structures at the EU level resulting from the ongoing financial crisis, the government decided to temporarily postpone the previously planned opt-out referendums. After a new government came to power in September 2011, they stated that the next euro referendum would not be held during its upcoming four-year term due to this uncertainty. At the same time, opinion polls showed a rapid decline in support for euro adoption.[94]

United Kingdom

The British currency is the pound sterling and the country has an opt-out from eurozone membership. The Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government elected in 2010 has pledged not to join the euro during its term of office,[95] due to expire in 2015.

The United Kingdom redesigned most of its coinage in 2008. The German newspaper Der Spiegel saw this as an indication that the country has no intention of switching to the euro within the foreseeable future.[96] In December 2008, José Barroso, the President of the European Commission, told French radio that some British politicians were considering the move because of the effects of the global credit crisis; the office of the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, denied that there was any such change in official policy.[97] In February 2009, Monetary Policy Affairs Commissioner Joaquín Almunia said "The chance that the British pound sterling will join: high."[98]

The Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia introduced the euro at the same time as Cyprus, on 1 January 2008. Previously, they used the Cypriot Pound. They do not have separate euro coins.

Outside the EU

It is the principle that no area is allowed to join the Eurozone without being member of the European Union. Some dependent territories of a Eurozone member country, have been allowed to use the euro without being part of the EU, for example Saint Pierre and Miquelon.

Iceland

During the 2008–2011 Icelandic financial crisis, instability in the Icelandic króna led to discussion in Iceland about adopting the euro. However, Jürgen Stark, a Member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, has stated that "Iceland would not be able to adopt the EU currency without first becoming a member of the EU".[99] Iceland subsequently applied for EU membership. As of the ECB's May 2012 convergence report, Iceland did not meet any of the convergence criteria.[100] One year later, the country managed to comply with the deficit criteria and had begun to decrease their debt-to-GDP ratio,[21] but still suffered from elevated HICP inflation and long-term governmental interest rates.[8][10]

Dependent territories of EU member states

The euro has also been adopted by four dependent territories of EU member states which are not part of the EU: Akrotiri and Dhekelia, Saint-Barthélemy, Saint Pierre et Miquelon and French Southern and Antarctic Lands.

Faroe Islands

The Danish krone is currently used by both of its dependent territories, Greenland and Faroe Islands, with their monetary policy controlled by the Danish Central Bank.[101] If Denmark does adopt the euro, separate referendums would be required in both territories to decide whether they should follow suit. Both territories have voted not to be a part of the EU in the past, and their populations will not participate in the Danish euro referendum.[102] The Faroe Islands utilise a special version of the Danish krone notes that have been printed with text in the Faroese language.[103] It is regarded as a foreign currency, but can be exchanged 1:1 with the Danish version.[101][103] On 5 November 2009 the Faroese Parliament approved a proposal to investigate the possibility for euro adoption, including an evaluation of the legal and economic impact of adopting the euro ahead of Denmark.[104][105][106][107] The answer seems to have been that it would not be legally possible.

New Caledonia, French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna

The French overseas collectivities French Polynesia and Wallis and Futuna have declared themselves in favour of joining the eurozone, replacing the CFP franc with the euro. However, New Caledonia has not yet made any decision, because an independence referendum may be held in 2014 or later, and opinions differ about whether the euro should be used or not in the future. The French government has required that all three entities will have to decide in favour to join. After such a decision, the government would make the application on their behalf at the European Council, and the switch to euro could be made after a couple of years.[108]

Summary of adoption progress

| Non-eurozone member state | Currency (Code) |

Central rate per €1[109] | EU join date | ERM II join date[109] | Government policy on euro adoption | Convergence criteria compliance[110] (as of June 2024) |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lev (BGN) |

1.95583[nb 1] | 2007-01-01 | 2020-07-10 | Euro by 2025[112] | Compliant with 4 out of 5 criteria (all except inflation) | ||

| Koruna (CZK) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Assessment of joining ERM-II to be completed by October 2024[113] | Compliant with 2 out of 5 criteria | ||

| Krone (DKK) |

7.46038 | 1973-01-01 | 1999-01-01 | Not on government's agenda[114][115] | Not assessed due to opt-out from eurozone membership | Rejected euro adoption by referendum in 2000 | |

| Forint (HUF) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[116] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Złoty (PLN) |

Free floating | 2004-05-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[117] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Leu (RON) |

Free floating | 2007-01-01 | None | ERM-II by 2026 and euro by 1 January 2029[118][119][120] | Not compliant with any of the 5 criteria | ||

| Krona (SEK) |

Free floating | 1995-01-01 | None | Not on government's agenda[121] | Compliant with 2 out of 5 criteria | Rejected euro adoption by referendum in 2003. Still obliged to adopt the euro once compliant with all criteria.[nb 2] |

The 13 new EU member states, who joined the union in 2004, 2007 and 2013, shall adopt the euro as soon as they meet the criteria. For them, the single currency was "part of the package" of European Union membership. Unlike for the UK and Denmark, "opting out" from the third stage of the EMU is not permitted. Currently 6 of the new members have adopted the euro:

- Slovenia (1 January 2007)

- Cyprus (1 January 2008)

- Malta (1 January 2008)

- Slovakia (1 January 2009)

- Estonia (1 January 2011)

- Latvia (1 January 2014)

Article 140 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union requires the European Commission and the ECB to report to the Ecofin Council at least once every two years, or at the request of a Member State with a "euro derogation", on the progress made by states to comply with the euro adoption criteria and their suitability to join the eurozone. The first report to include the 10 new 2004-members was published in October 2004.[122] The most recent report was published 4 June 2014, and covered the 7 remaining non-euro member states without an opt-out: Lithuania, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Sweden.[43] Lithuania's adoption of the euro on 1 January 2015 was given final approval by the Council of the European Union on 23 July 2014.[4]

As reported by the table below, the remaining seven new EU members are expected to take longer to adopt the euro. This is in part due to the challenges caused by the 2008 financial crisis, as well as the necessity for their economies to catch-up to European standards after recently joining the EU's internal market, before being able to comply with all the economic convergence criteria.[123] Each country aspiring to adopt the euro has been requested by the European Commission to develop a "strategy for criteria compliance" and "national euro changeover plan". In the "changeover plan", the country can select from between three scenarios for euro adoption:[124]

- Madrid scenario (with a transition period between euro adoption day and the physical circulation of euros)

- Big-bang scenario (euro adoption day coincides with the first day of circulating euros)

- Big-bang scenario with phaseout (the same as the second scenario, but with a transitional period for legal documents -like contracts- to be denoted in euros)

The second scenario is recommended for candidate countries, while the third is only advised if at a late stage in the preparational process they experience technical difficulties (i.e. with IT-systems), which would make an extended transitional period for the phasing out of the old currency at the legal level a necessity.[124] The European Commission has published a handbook detailing how states should prepare for the changeover. It recommends that a national steering committee plan the following five actions to prepare the country for the changeover several months ahead of euro adoption day:[125]

- Prepare the public with an information campaign and dual price display.

- Prepare the public sectors introduction at the legal level.

- Prepare the private sectors introduction at the legal level.

- Prepare the vending machine industry so that they can deliver adjusted and quality tested vending machines.

- Frontload banks as well as public and private retail sector several months ahead of the euro adoption with their needed supply of euro coins and notes, which is a process usually initiated by prior countries in September (as ECB regulated[126] the first frontload is allowed at the earliest four months ahead of the euro adoption date).

The table below summarizes each candidate country's national plan for euro adoption and currency changeover.[127]

| State | Official target for euro adoption[128] | ERM II entry |

Coordinating institution | Changeover plan (latest version) |

Introduction[129] | Dual circulation period |

Exchange of coins till | Dual price display | National mint | Coin design | Currency needed (in units) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not set | Not set | – | Strategy plan (signed Nov.2004)[130] |

– | – | – | – | Yes | Approved | – | |

| Not set (Not before 1 Jan 2019[59]) |

Not before 2016[59] | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | Competition under consideration |

– | |

| Not set | Not before 2015[71] | National Coordination Group (established Feb.2006) |

Changeover plan (approved Apr.2007)[131] |

Big-Bang | 2 weeks | Banks: 6 months, Central bank: 5 years |

Start 1 month after Council approval of euro adoption, and lasts until 12 months after adoption | Public tender | Competition under consideration |

– | |

| Opt-out (A referendum is planned for after the next general election) |

1 January 1999 | – | The original plan from 2000,[132] is no longer valid. A new plan will be made ahead of the planned referendum. | Madrid scenario (outlined by the 2000 plan) |

2 months | Central bank: 30 years |

4 weeks after euro circulation | Yes | In 2000 a possible coin design was published [133] | 123 million banknotes and 1300 million coins[132] | |

| Not set | Not set | National Euro Coordination Committee (established Sep.2007) |

Changeover plan (approved Nov.2009)[134][135] |

Big-Bang | less than 1 month (not decided yet) |

Central bank: 5 years |

Start 1 day after Council approval of euro adoption, and lasts until 6 months after adoption | – | Not yet decided |

– | |

| 1 January 2015 | 28 June 2004 | Commission for the Coordination of the Adoption of the euro in Lithuania (established Feb.2013) |

Changeover plan (approved Jun.2013)[136] Changeover law (passed Apr.2014)[137] |

Big-Bang | 15 days | Banks: 6 months Central bank: infinity |

Start 30 days after Council approval of euro adoption, equal to 22 Aug.2015, and lasts until 12 months after adoption | Yes[38] | Approved | 132 million banknotes, 370 million coins[138] | |

| Not set | Not set | The Government Plenipotentiary for the Euro Adoption in Poland, and National Coordination Committee for Euro Changeover, and Coordinating Council (all established Nov.2009) |

Changeover plan (approved in 2011, but an updated plan is under preparation)[nb 3] |

– | – | – | – | – | Public survey under consideration |

– | |

| 1 January 2019[87][88] | Not set | Interministerial Committee for changeover to euro (established May 2011) |

– | – | 11 months[140] | – | – | – | Not yet decided |

– | |

| De facto opt-out[nb 2] (The Swedish government has made joining the euro subject to approval by a referendum) |

Not under consideration (The Swedish National Bank's monetary policy is to not peg the SEK to the euro as long as there is no referendum approving euro adoption) |

– | – | – | – | – | – | – | Not yet decided |

– | |

| Opt-out | Not under consideration | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The 2008 financial crisis caused a delay in the schedule for adoption of the euro for most of the new EU members. The convergence progress for the newly accessed EU member states, is supported and evaluated by the yearly submission of the "Convergence programme" under the Stability and Growth Pact. As a general rule, the majority of economic experts recommend for newly accessed EU member states with a forecasted era of catching-up and a past record of "macro-economic imbalance" or "financial instability", that these countries first use some years to address these issues and ensure "stable convergence", before taking the next step to join the ERM-II, and as the final step (when complying with all convergence criteria) ultimately adopt the euro. In practical terms, any non-euro EU member state can become an ERM-II member whenever they want, as this mechanism does not define any criteria to comply with. Economists however consider it to be more desirable for "unstable countries", to maintain their flexibility of having a floating currency, rather than getting an inflexible and partly fixed currency as an ERM-II member. Only at the time of being considered fully "stable", the member states will be encouraged to enter into ERM-II, and then ultimately recommended to apply for the euro membership minimum two years later.[123]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ The Bulgarian National Bank pursues its primary objective of price stability through an exchange rate anchor in the context of a Currency Board Arrangement (CBA), obliging them to exchange monetary liabilities and euro at the official exchange rate 1.95583 BGN/EUR without any limit. The CBA was introduced on 1 July 1997 as a 1:1 peg against German mark, and the peg subsequently changed to euro on 1 January 1999.[111]

- ^ a b Sweden, while obliged to adopt the euro under its Treaty of Accession, has chosen to deliberately fail to meet the convergence criteria for euro adoption by not joining ERM II without prior approval by a referendum.

- ^ Cite from the 2014 Polish convergence report: Due to the significant reform agenda in the European Union and in the euro area, the current objective is to update the National Euro Changeover Plan with reference to the impact of those changes on Poland’s euro adoption strategy. The date of completion of the document is conditional on the adoption of binding solutions on the EU forum concerning the key institutional changes, in particular, those referring to the banking union. The outcome of these changes determines the area of the necessary institutional and legal adjustments as well as the national balance of costs and benefits arising from introduction of the common currency.[139]

References

- ^ Kubosova, Lucia (5 May 2008). "Slovakia confirmed as ready for Euro". euobserver.com. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ "Ministers offer Estonia entry to eurozone January 1". France24.com. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Latvia becomes the 18th Member State to adopt the euro". European Commission. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "Lithuania to adopt the euro on 1 January 2015". Council of the European Union. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ "The euro outside the euro area". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "The government announces a contest for the design of the Andorran euros". Andorra Mint. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Lithuanian PM keen on fast-track euro idea". London South East. 7 April 2007.

- ^ a b "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2024. Cite error: The named reference "12-months average of Annual HICP rates reported by Eurostat on a monthly basis" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012. Cite error: The named reference "Long-term interest rate (monthly EMU data for the past year)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Convergence Report June 2024" (PDF). European Central Bank. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Convergence Report 2024" (PDF). European Commission. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- ^ a b "European economic forecast – Winter 2013" (PDF). European Commission. 22 February 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Release Calendar for Euro Indicators". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Convergence Report (May 2012)" (PDF). ECB. May 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- ^ "New EU members to break free from euro duty". http://www.euractiv.com. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Adoption of the euro in Lithuania". Bank of Lithuania. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- ^ "Lithuanian PM says aiming for euro by 2010–2011". Forbes. 12 April 2007. Retrieved 3 January 20083.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ Pavilenene, Danuta (8 December 2008). "SEB: no euro for Lithuania before 2013". The Baltic Course. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "FEATURE – Crisis, not Greece, makes euro hopefuls cautious". Reuters. 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Lithuanian PM keen on fast-track euro idea". The Baltic Course. 8 April 2009.

- ^ "Lithuania to Adopt Euro When Europe Is Ready, Kubilius Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "Foreign Minister: 'Lithuania could adopt the euro after some time'". EurActiv. 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Lithuanian voters to give harsh verdict on austerity". reuters. 14 October 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "lithuania pm candidate targets 2015 euro adoption". yahoo.

- ^ "Lithuania's next prime minister still hopes to adopt euro in 2014". 15min.lt. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ Bradley, Bryan (25 January 2013). "Lithuania Commits to Seek Euro Adoption in 2015". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ "Lithuanian government endorses euro introduction plan". 15 min. 25 February 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Euro Banknotes and Coins". Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Projects for Lithuanian euro coins already bear the year 2015". Bank of Lithuania. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Lithuania readies for euro adoption". BalticTimes.com. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "Commission assesses eight EU countries' readiness to join the euro area; proposes that Lithuania join in 2015". European Commission. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "ECB publishes its Convergence Report 2014". European Central Bank. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Commission. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Convergence Report 2014" (PDF). European Central Bank. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ "European Parliament gives go-ahead for Lithuania to join the euro". European Parliament. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- ^ European Parliament greenlights Lithuania's euro adoption

- ^ "Bulgaria's budget of reform". The Sofia Echo. 30 November 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- ^ "Bulgaria could join euro zone ahead of other eu countries".

- ^ "said to pressure Bulgaria into discontinuing currency board".

- ^ "The Sofia Echo". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ byDnevnik.bg (17 September 2009). "Bulgaria to seek eurozone entry within GERB's term – Finance Minister". Sofia Echo. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ M3 Web – http://m3web.bg (22 December 2009). "Bulgaria: Bulgaria to Apply for ERM 2 in March". Sofia. Novinite. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

{{cite news}}: External link in|author= - ^ "Bulgaria delays eurozone application as deficit soars". Eubusiness.com. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "Bulgaria's Eurozone accession drifts away". Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- ^ "Bulgaria puts off Eurozone membership for 2015". Radio Bulgaria. 26 July 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ "Bulgaria: Frontier country report" (PDF). Deutche Bank Research. 23 May 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ "Bulgaria shelves euro membership plans". EUobserver.com. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- ^ Pawlak, Justyna (10 June 2011). "Croatia ready to join EU in 2013 – official". reuters.com.

- ^ THOMSON, AINSLEY. "Croatia Aims for Speedy Adoption of Euro". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Konferencija HNB-a u Dubrovniku: Hrvatska može uvesti euro najranije 2019" (in Croatian). HNB. 14 June 2013.

- ^ a b "Czechs, Poles cooler to euro as they watch debt crisis". Reuters. 16 June 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ a b "Convergence Programme of the Czech Republic (April 2013)" (PDF). Ministry of Finance (Czech Republic). 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ "Czech crown to stay long with no euro opt-out needed: PM". Reuters. 5 December 2010.

- ^ Laca, Peter (5 December 2010). "Czech Republic Still Able to Opt Out of Adopting Euro, Prime Minister Says". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (28 October 2011). "Czech PM mulls euro referendum". EUObserver. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

"The conditions under which the Czech citizens decided in a referendum in 2003 on the country's accession to the EU and on its commitment to adopt the single currency, euro, have changed. That is why the ODS will demand that a possible accession to the single currency and the entry into the European stabilisation mechanism be decided on by Czech citizens," the ODS resolution says.

- ^ "Czechs deeply divided on EU's fiscal union". Radio Praha. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "ForMin: Euro referendum casts doubt on Czech pledges to EU". Prague Daily Monitor. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ "Týden: Future to clear up diplomatic myths about new president". Prague Daily Monitor. 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2013-023-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bilefsky, Dan (1 March 2013). "Czechs Split Deeply Over Joining the Euro". The New York Times.

- ^ "New Czech president will approve ESM". 11 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Skeptical Czechs may be pushed to change tone on euro". Reuters. 26 April 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ a b "CNB and MoF recommend not to set euro adoption date yet". Czech National Bank. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "Orbán: We won't have euro until 2020.(In Hungarian.)". Index. 5 February 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Matolcsy: Hungarian euro is possible in 2020.(In Hungarian.)". Világgazdaság. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- ^ "Poland may adopt euro before 2014-Deputy FinMin". Forbes. 10 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ "Official: Poland to be ready for euro in 4 years". Bloomberg Businessweek. 2 December 2011.

- ^ "As much as 58% of Poles are against the euro" (in Polish). Forbes.pl. 5 June 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ "Wg raportu GMF Polacy coraz bardziej nie lubią USA, NATO, Obamy i Rosji". Wiadomości. 12 September 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ Sobczyk, Marcin (5 June 2012). "Euro's Popularity Hits Record Low in Poland". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Monetary policy guidelines for 2013 (print nr.764)" (PDF). The Monetary Policy Council of the Polish National Bank (page 9) (in Polish). Sejm. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ^ "Raport privind situația macroeconomică" (PDF). Government of Romania. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ "Romania to join the euro zone in 2015". Business Review. 1 November 2011.

- ^ "Update: New Euro adoption target to be set by the end of the month, PM". http://business-review.eu. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Government of Romania: 2012–15 Convergence Programme" (PDF). European Commission. 30 April 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Bilefsky, Dan (3 November 2012). "Resilient Romania Finds a Currency Advantage in a Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ "Government of Romania - Convergence Programme - 2013-2016" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2013.

- ^ a b Trotman, Andrew (18 April 2013). "Romania abandons target date for joining euro". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ a b "Government of Romania - Convergence programme - 2014-2017" (PDF). Government of Romania. April 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Romania Sets 2019 as Target Date to Join Euro Area, Voinea Says". Bloomberg. 6 May 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "European Union Agreement Details". Council of the European Union. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Folkomröstning 14 september 2003 om införande av euron" (in Swedish). Swedish Election Authority. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- ^ "Glöm euron, Reinfeldt" (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 2 December 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ "Summary of hearing of Olli Rehn – Economic and Monetary Affairs (Hearings - Institutions - 12-01-2010 - 09:39)". European Parliament. 11 January 2101. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

Olle Schmidt (ALDE, SE) inquired whether Sweden could still stay out of the Eurozone. Mr Rehn replied that it is up to the Swedish people to decide on the issue.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stratton, Allegra (22 November 2007). "Danes to hold referendum on relationship with EU". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ "Debt Crisis Pushes Danish Euro Opposition to Record, Poll Shows". Bloomberg. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "At-a-glance: Cameron coalition's policy plans". BBC News. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ "Make Way for Britain's New Coin Designs". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ "No 10 denies shift in euro policy". BBC. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-EU's Almunia: high chance UK to join euro in future". in.reuters.com. 2 February 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ^ "Iceland cannot adopt the Euro without joining EU, says Stark". IceNews. 23 February 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Document A: Presentation by Bodil Nyboe Andersen "Økonomien i rigsfællesskabet"" (PDF) (in Danish). Føroyskt Løgting. 25 May 2004. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Use of Euro in Affiliated Countries and Territories Outside the EU". Danmarks Nationalbank. June 2000. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ a b "The Faroese banknote series". Danmarks Nationalbank. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ "Løgtingsmál nr. 11/2009: Uppskot til samtyktar um at taka upp samráðingar um treytir fyri evru sum føroyskt gjaldoyra" (PDF) (in Faroese). 4 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Rich Faroe Islands may adopt euro". Fishupdate.com. 12 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Euro wanted as currency in Faroe Islands". Icenews.is. 8 August 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "11/2009: Uppskot consenting to undertake conversations of trust for introducing euro as a Faroese currency (second reading)" (in Faroese). Føroyskt Løgting. 5 November 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ "Nouvelle-Calédonie : Entre Émancipation, Passage A L'Euro Et Recherche De Ressources Nouvelles" (PDF). Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Foreign exchange operations". European Central Bank. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Convergence Report June 2024" (PDF). European Central Bank. 26 June 2024. Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ "EUROPEAN ECONOMY 4/2014: Convergence Report 2014" (PDF). European Commission. 4 June 2014.

- ^ "Bulgaria meets all criteria, only inflation remains for eurozone membership, according to the regular convergence reports for 2024 of the European Commission and the European Central Bank". Unity Is Strength (in Bulgarian). Ministry of Finance (Bulgaria). 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Czech Government to Evaluate Merits of Joining 'Euro Waiting Room'". Reuters. 7 February 2024. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ "Denmark's Zeitenwende". European Council on Foreign Relations. 7 June 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2024.

- ^ "Regeringsgrundlag December 2022: Ansvar for Danmark (Government manifest December 2022: Responsibility for Denmark)" (PDF) (in Danish). Danish Ministry of Finance. 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Orbán: Hungary will not adopt the euro for many decades to come". Hungarian Free Press. 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Poland is still not ready to adopt the euro, its finance minister says". Ekathimerini.com. 30 April 2024.

- ^ Smarandache, Maria (20 March 2023). "Romania wants to push euro adoption by 2026". Euractiv.com. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Smarandache, Maria (24 March 2023). "Iohannis: No 'realistic' deadline for Romania to join eurozone". Euractiv.com. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Balázs Márton (20 March 2023). "Románia előrébb hozná az euró bevezetését" [Romania would advance the introduction of the euro]. Telex.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "DN Debatt Repliker. 'Folkligt stöd saknas för att byta ut kronan mot euron'" [DN Debate Replicas. "There is no popular support for exchanging the krona for the euro"]. Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). 3 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Convergence Report". European Central Bank. 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2006.

- ^ a b "The acceding countries' strategies towards ERM II and the adoption of the euro: an analytical review" (PDF). ECB. February 2004. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Adopting the euro: Scenarios for adopting the euro". 20 March 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Preparing the introduction of the euro – a short handbook" (PDF). European Commission. 15 April 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Unofficial consolidated text: Guideline of the ECB of 19 June 2008 amending Guideline ECB/2006/9 on certain preparations for the euro cash changeover and on frontloading and sub-frontloading of euro banknotes and coins outside the euro area (ECB/2008/4)(OJ L 176)" (PDF). ECB. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ^ "Thirteenth Report on the practical preparations for the future enlargement of the euro area" (PDF). European Commission. 3 December 2013.

- ^ "Adopting the euro: Who can join and when". 17 July 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Scenarios for adopting the euro". http://ec.europa.eu/. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Agreement between the Council of Ministers and the Bulgarian National Bank on the introduction of the Euro in the Republic of Bulgaria" (PDF). Bulgarian National Bank. 26 November 2004.

- ^ http://www.zavedenieura.cz/cps/rde/xbcr/euro/NP_EN_06-08-07.pdf

- ^ a b "Overgang til euro ved dansk deltagelse" (PDF). Økonomiministeriet. 14 June 2000. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ "Illustration af danske euromønter" (in Danish). http://www.eu-oplysningen.dk. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ http://www.mnb.hu/Root/Dokumentumtar/MNB/MNBEuro_Index/A_jegybank/euro_main_1/nat_2009_hu_vegleges.pdf

- ^ "National Changeover Plan for Hungary" (PDF). Magyar Nemzeti Bank. 12 December 2008.

- ^ http://www3.lrs.lt/pls/inter3/dokpaieska.showdoc_l?p_id=453080&p_query=&p_tr2=2

- ^ "Lithuania readies for euro adoption". BalticTimes.com. 1 May 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ "The first Lithuanian euro coins are being minted by order of the Bank of Lithuania". Lietuvos Bankas. 16 June 2014.

- ^ "Convergence programme: 2014 update" (PDF). Republic of Poland. April 2014.

- ^ "Guvernanţi: România poate adopta euro în 2015" (in Romanian). Evenimentul Zilei. 29 April 2011.