Lernaean Hydra: Difference between revisions

→The Second Labour ("άθλος") of Heracles: added content Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

The Hydra was one of the offspring of [[Typhon]] and [[Echidna (mythology)|Echidna]] (''[[Theogony]]'', 313), both of whom were noisome offspring of the earth goddess [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]].<ref>For other [[chthonic]] monsters said in various sources to be ancient offspring of Hera, the [[Nemean Lion]], the [[Stymphalian birds]], the [[Chimera (mythology)|Chimaera]], and [[Cerberus]].</ref> |

The Hydra was one of the offspring of [[Typhon]] and [[Echidna (mythology)|Echidna]] (''[[Theogony]]'', 313), both of whom were noisome offspring of the earth goddess [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]].<ref>For other [[chthonic]] monsters said in various sources to be ancient offspring of Hera, the [[Nemean Lion]], the [[Stymphalian birds]], the [[Chimera (mythology)|Chimaera]], and [[Cerberus]].</ref> |

||

==The Second Labour |

==The Second Labour of Heracles== |

||

[[Eurystheus]] sent Heracles to slay the Hydra, which [[Hera]] had raised just to slay Heracles. Upon reaching the swamp near [[Lerna|Lake Lerna]], where the Hydra dwelt, [[Heracles]] covered his mouth and nose with a cloth to protect himself from the poisonous fumes. He fired flaming arrows into the Hydra's lair, the spring of [[Amymone]], a deep cave that it only came out of to terrorize neighboring villages.<ref>Kerenyi, ''The Heroes of the Greeks'', 1959:144.</ref> He then confronted the Hydra, wielding a harvesting [[sickle]] (according to some early vase-paintings), a sword or his famed club. Ruck and Staples (1994: 170) have pointed out that the [[chthonic]] creature's reaction was botanical: upon cutting off each of its heads he found that two grew back, an expression of the hopelessness of such a struggle for any but the [[hero]]. The weakness of the Hydra was that it was invulnerable only if it retained at least one head. |

[[Eurystheus]] sent Heracles to slay the Hydra, which [[Hera]] had raised just to slay Heracles. Upon reaching the swamp near [[Lerna|Lake Lerna]], where the Hydra dwelt, [[Heracles]] covered his mouth and nose with a cloth to protect himself from the poisonous fumes. He fired flaming arrows into the Hydra's lair, the spring of [[Amymone]], a deep cave that it only came out of to terrorize neighboring villages.<ref>Kerenyi, ''The Heroes of the Greeks'', 1959:144.</ref> He then confronted the Hydra, wielding a harvesting [[sickle]] (according to some early vase-paintings), a sword or his famed club. Ruck and Staples (1994: 170) have pointed out that the [[chthonic]] creature's reaction was botanical: upon cutting off each of its heads he found that two grew back, an expression of the hopelessness of such a struggle for any but the [[hero]]. The weakness of the Hydra was that it was invulnerable only if it retained at least one head. |

||

Revision as of 09:17, 18 December 2014

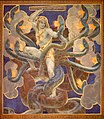

The 19th-century French artist Gustave Moreau was influenced by the Beast of Revelation in his depiction of the Hydra. | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Serpent-like water spirit |

| Other name(s) | Greek Hydra |

| Country | Greece |

In Greek mythology, the Lernaean Hydra (Greek: Λερναῖα Ὕδρα) was an ancient serpent-like water monster with reptilian traits. It possessed many heads – the poets mention more heads than the vase-painters could paint – and for each head cut off it grew two more. It had poisonous breath and blood so virulent that even its tracks were deadly.[1] The Hydra of Lerna was killed by Heracles as the second of his Twelve Labours. Its lair was the lake of Lerna in the Argolid, though archaeology has borne out the myth that the sacred site was older even than the Mycenaean city of Argos since Lerna was the site of the myth of the Danaids. Beneath the waters was an entrance to the Underworld, and the Hydra was its guardian.[2]

The Hydra was one of the offspring of Typhon and Echidna (Theogony, 313), both of whom were noisome offspring of the earth goddess Gaia.[3]

The Second Labour of Heracles

Eurystheus sent Heracles to slay the Hydra, which Hera had raised just to slay Heracles. Upon reaching the swamp near Lake Lerna, where the Hydra dwelt, Heracles covered his mouth and nose with a cloth to protect himself from the poisonous fumes. He fired flaming arrows into the Hydra's lair, the spring of Amymone, a deep cave that it only came out of to terrorize neighboring villages.[4] He then confronted the Hydra, wielding a harvesting sickle (according to some early vase-paintings), a sword or his famed club. Ruck and Staples (1994: 170) have pointed out that the chthonic creature's reaction was botanical: upon cutting off each of its heads he found that two grew back, an expression of the hopelessness of such a struggle for any but the hero. The weakness of the Hydra was that it was invulnerable only if it retained at least one head.

The details of the struggle are explicit in the Bibliotheca (2.5.2): realizing that he could not defeat the Hydra in this way, Heracles called on his nephew Iolaus for help. His nephew then came upon the idea (possibly inspired by Athena) of using a firebrand to scorch the neck stumps after each decapitation. Heracles cut off each head and Iolaus cauterized the open stumps. Seeing that Heracles was winning the struggle, Hera sent a large crab to distract him. He crushed it under his mighty foot. The Hydra's one immortal head was cut off with a golden sword given to him by Athena. Heracles placed the head – still alive and writhing – under a great rock on the sacred way between Lerna and Elaius (Kerenyi 1959:144), and dipped his arrows in the Hydra's poisonous blood, and so his second task was complete. The alternative version of this myth is that after cutting off one head he then dipped his sword in it and used its venom to burn each head so it couldn't grow back. Hera, upset that Heracles had slain the beast she raised to kill him, placed it in the dark blue vault of the sky as the constellation Hydra. She then turned the crab into the Constellation Cancer.

Heracles would later use arrows dipped in the Hydra's poisonous blood to kill other foes during his remaining Labours, such as Stymphalian Birds and the giant Geryon. He later used one to kill the centaur Nessus; and Nessus' tainted blood was applied to the Tunic of Nessus, by which the centaur had his posthumous revenge. Both Strabo and Pausanias report that the stench of the river Anigrus in Elis, making all the fish of the river inedible, was reputed to be due to the Hydra's poison, washed from the arrows Heracles used on the centaur.[5]

When Eurystheus, the agent of ancient Hera who was assigning The Twelve Labors to Heracles, found out that it was Heracles' nephew Iolaus who had handed him the firebrand, he declared that the labor had not been completed alone and as a result did not count towards the 10 Labours set for him. The mythic element is an equivocating attempt to resolve the submerged conflict between an ancient ten Labours and a more recent twelve.

Heracles and the hydra in art

-

Mosaic from Roman Spain (26 AD)

-

Silver sculpture (1530s)

-

Engraving (1) by Hans Sebald Beham

-

Gustave Moreau (1861)

-

John Singer Sargent (1921)

Constellation

Mythographers relate that the Lernaean Hydra and the crab were put into the sky after Heracles slew them. In an alternative version, Hera's crab was at the site to bite his feet and bother him, hoping to cause his death. Hera set it in the Zodiac to follow the Lion (Eratosthenes, Catasterismi). When the sun is in the sign of Cancer, the crab, the constellation Hydra has its head nearby.

In popular culture

- The Beast mentioned in the Book of Revelation has all the features of a Hydra, and it is generally understood as an allegory of the Roman Empire, especially during the years of Nero and the Great Fire of Rome.

- Jason and the Argonauts featured a battle between Jason and a Hydra.

- The Disney animated film Hercules features the Hydra, which Hercules fights and defeats by causing an avalanche that crushes it.

- Hydra was a 2009 low-budget monster movie.

- HYDRA is a global terrorist organization in the Marvel universe.

Notes

- ^ "This monster was so poisonous that she killed men with her breath and excretion. If anyone passed by when she was sleeping, he breathed her tracks and died in the greatest torment." (Hyginus, 30).

- ^ Kerenyi (1959), 143.

- ^ For other chthonic monsters said in various sources to be ancient offspring of Hera, the Nemean Lion, the Stymphalian birds, the Chimaera, and Cerberus.

- ^ Kerenyi, The Heroes of the Greeks, 1959:144.

- ^ Strabo, viii.3.19, Pausanias, v.5.9; Grimal 1987:219.

References

- Primary sources

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca ii.5.2

- Secondary sources

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1903). Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

- Graves, Robert (1955). The Greek Myths.

- Kerenyi, Carl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks.

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Harvard University Press.

- Ruck, Carl and Staples, Danny (1994). The World of Classical Myth.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Grimal, Pierre (1986). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc.

- Piccardi, Luigi (2005). The head of the Hydra of Lerna (Greece). Archaeopress, British Archaeological Reports, International Series N° 1337/2005, 179-186.