Minkowski space: Difference between revisions

→The Minkowski inner product: Replacing explanation so that it ties in directly with the definition of subadditivity; also making it into a footnote |

→Standard basis: there is no basis for talking about absolute values here; the absolute value of this has no physical meaning or significance. |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

In terms of components, the inner product between two vectors ''v'' and ''w'' is given by |

In terms of components, the inner product between two vectors ''v'' and ''w'' is given by |

||

:<math>\langle v, w \rangle = \eta_{\mu \nu} v^\mu w^\nu = - v^0 w^0 + v^1 w^1 + v^2 w^2 + v^3 w^3 </math> |

:<math>\langle v, w \rangle = \eta_{\mu \nu} v^\mu w^\nu = - v^0 w^0 + v^1 w^1 + v^2 w^2 + v^3 w^3 </math> |

||

and the norm-squared of a vector ''v'' is |

and the norm-squared of a vector ''v'' is |

||

:<math>v^2 = \eta_{\mu \nu} v^\mu v^\nu = - (v^0)^2 + (v^1)^2 + (v^2)^2 + (v^3)^2</math> |

:<math>v^2 = \eta_{\mu \nu} v^\mu v^\nu = - (v^0)^2 + (v^1)^2 + (v^2)^2 + (v^3)^2</math> |

||

Revision as of 19:31, 26 February 2015

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Special relativity |

|---|

|

In mathematical physics, Minkowski space or Minkowski spacetime (named after the mathematician Hermann Minkowski) is the mathematical space setting in which Einstein's theory of special relativity is most conveniently formulated. In this setting the three ordinary dimensions of space are combined with a single dimension of time to form a four-dimensional manifold for representing a spacetime.

In theoretical physics, Minkowski space is often contrasted with Euclidean space. While a Euclidean space has only spacelike dimensions, a Minkowski space also has one timelike dimension. The isometry group of a Euclidean space is the Euclidean group and for a Minkowski space it is the Poincaré group.

The spacetime interval between two events in Minkowski space is either space-like, light-like ('null') or time-like.

History

In 1905, with the publication in 1906, it was noted by Henri Poincaré that, by taking time to be the imaginary part of the fourth spacetime coordinate √−1 ct, a Lorentz transformation can be regarded as a rotation of coordinates in a four-dimensional Euclidean space with three real coordinates representing space, and one imaginary coordinate, representing time, as the fourth dimension. Since the space is then a pseudo-Euclidean space, the rotation is a representation of a hyperbolic rotation, although Poincaré did not give this interpretation, his purpose being only to explain the Lorentz transformation in terms of the familiar Euclidean rotation.[1] This idea was elaborated by Hermann Minkowski,[2] who used it to restate the Maxwell equations in four dimensions, showing directly their invariance under the Lorentz transformation. He further reformulated in four dimensions the then-recent theory of special relativity of Einstein. From this he concluded that time and space should be treated equally, and so arose his concept of events taking place in a unified four-dimensional space-time continuum. In a further development,[3] he gave an alternative formulation of this idea that did not use the imaginary time coordinate, but represented the four variables (x, y, z, t) of space and time in coordinate form in a four dimensional affine space. Points in this space correspond to events in space-time. In this space, there is a defined light-cone associated with each point (see diagram above), and events not on the light-cone are classified by their relation to the apex as space-like or time-like. It is principally this view of space-time that is current nowadays, although the older view involving imaginary time has also influenced special relativity. Minkowski, aware of the fundamental restatement of the theory which he had made, said:

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality. – Hermann Minkowski, 1908

For further historical information see references Galison (1979), Corry (1997), Walter (1999).

Structure

Formally, Minkowski space is a four-dimensional real vector space equipped with a nondegenerate, symmetric bilinear form with signature (−,+,+,+) (Some may also prefer the alternative signature (+,−,−,−); in general, mathematicians and general relativists prefer the former while particle physicists tend to use the latter.) In other words, Minkowski space is a pseudo-Euclidean space with n = 4 and n − k = 1 (in a broader definition any n > 1 is allowed). Elements of Minkowski space are called events or four-vectors. Minkowski space is often denoted R1,3 to emphasize the signature, although it is also denoted M4 or simply M. It is perhaps the simplest example of a pseudo-Riemannian manifold.

The Minkowski inner product

This inner product is similar to the usual Euclidean inner product, but is used to describe a different geometry; the geometry is usually associated with relativity. Let M be a 4-dimensional real vector space. The Minkowski inner product is a map η: M × M → R (i.e. given any two vectors v, w in M we define η(v,w) as a real number) which satisfies properties (1), (2), and (3) listed here, as well as property (4) given below:

1. bilinear η(au+v, w) = aη(u,w) + η(v,w) for all a ∈ R and u, v, w in M.

2. symmetric η(v,w) = η(w,v) for all v, w ∈ M.

3. nondegenerate if η(v,w) = 0 for all w ∈ M then v = 0.

Note that this is not an inner product in the usual sense, since it is not positive-definite, i.e. the quadratic form η(v,v) need not be positive for nonzero v. The positive-definite condition has been replaced by the weaker condition of nondegeneracy (every positive-definite form is nondegenerate but not vice versa). The inner product is said to be indefinite. These misnomers, "Minkowski inner product" and "Minkowski metric," conflict with the standard meanings of inner product and metric in pure mathematics; as with many other misnomers, the usage of these terms is due to similarity to the mathematical structure.

Just as in Euclidean space, two vectors v and w are said to be orthogonal if η(v,w) = 0. Minkowski space differs by including hyperbolic-orthogonal events in case v and w span a plane where η takes negative values. This difference is clarified by comparing the Euclidean structure of the ordinary complex number plane to the structure of the plane of split-complex numbers. The Minkowski norm of a vector v is defined by

This is not a norm (and not even a seminorm) in the usual sense because it fails to be subadditive,[4] but it does define a useful generalization of the notion of length to Minkowski space. In particular, a vector v is called a unit vector if ||v|| = 1 (i.e., η(v,v) = ±1). A basis for M consisting of mutually orthogonal unit vectors is called an orthonormal basis.

By the Gram–Schmidt process, any inner product space satisfying conditions (1), (2), and (3) above always has an orthonormal basis. Furthermore, the number of positive and negative unit vectors in any such basis is a fixed pair of numbers, equal to the signature of the inner product. This is Sylvester's law of inertia.

Then the fourth condition on η can be stated:

4. signature The bilinear form η has signature (−,+,+,+) or (+,−,−,−).

Which signature is used is a matter of convention. Both are fairly common. See sign convention.

Standard basis

A standard basis for Minkowski space is a set of four mutually orthogonal vectors {e0,e1,e2,e3} such that

- −(e0)2 = (e1)2 = (e2)2 = (e3)2 = 1

These conditions can be written compactly in the following form:

where μ and ν run over the values (0, 1, 2, 3) and the matrix η is given by

- .

(As was previously noted, sometimes the opposite sign convention is preferred.)

This tensor is frequently called the "Minkowski tensor". Relative to a standard basis, the components of a vector v are written (v0,v1,v2,v3) and we use the Einstein notation to write v = vμeμ. The component v0 is called the timelike component of v while the other three components are called the spatial components.

In terms of components, the inner product between two vectors v and w is given by

and the norm-squared of a vector v is

Alternative definition

The section above defines Minkowski space as a vector space. There is an alternative definition of Minkowski space as an affine space which views Minkowski space as a homogeneous space of the Poincaré group with the Lorentz group as the stabilizer. See Erlangen program.

Note also that the term "Minkowski space" is also used for analogues in any dimension: if n≥2, n-dimensional Minkowski space is a vector space or affine space of real dimension n on which there is an inner product or pseudo-Riemannian metric of signature (n−1,1), i.e., in the above terminology, n−1 "pluses" and one "minus".

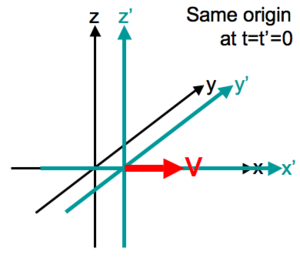

Lorentz transformations and symmetry

The Poincaré group is the group of all isometries of Minkowski spacetime including boosts, rotations, and translations. The Lorentz group is the subgroup of isometries which leave the origin fixed and includes the boosts and rotations; members of this subgroup are called Lorentz transformations. Among the simplest Lorentz transformations is a Lorentz boost. The archetypal Lorentz boost is

where

is the Lorentz factor, and

All four-vectors in Minkowski space transform according to the same formula under Lorentz transformations. Minkowski diagrams illustrate Lorentz transformations.

Causal structure

Vectors are classified according to the sign of η(v,v). When the standard signature (−,+,+,+) is used, a vector v is:

Timelike if η(v,v) < 0 Spacelike if η(v,v) > 0 Null (or lightlike) if η(v,v) = 0

This terminology comes from the use of Minkowski space in the theory of relativity. The set of all null vectors at an event of Minkowski space constitutes the light cone of that event. Note that all these notions are independent of the frame of reference. Given a timelike vector v, there is a worldline of constant velocity associated with it. The set {w : η(w,v) = 0 } corresponds to the simultaneous hyperplane at the origin of this worldline. Minkowski space exhibits relativity of simultaneity since this hyperplane depends on v. In the plane spanned by v and such a w in the hyperplane, the relation of w to v is hyperbolic-orthogonal.

Once a direction of time is chosen, timelike and null vectors can be further decomposed into various classes. For timelike vectors we have

- future directed timelike vectors whose first component is positive, and

- past directed timelike vectors whose first component is negative.

Null vectors fall into three classes:

- the zero vector, whose components in any basis are (0,0,0,0),

- future directed null vectors whose first component is positive, and

- past directed null vectors whose first component is negative.

Together with spacelike vectors there are 6 classes in all.

An orthonormal basis for Minkowski space necessarily consists of one timelike and three spacelike unit vectors. If one wishes to work with non-orthonormal bases it is possible to have other combinations of vectors. For example, one can easily construct a (non-orthonormal) basis consisting entirely of null vectors, called a null basis. Over the reals, if two null vectors are orthogonal (zero inner product), then they must be proportional. However, allowing complex numbers, one can obtain a null tetrad which is a basis consisting of null vectors, some of which are orthogonal to each other.

Vector fields are called timelike, spacelike or null if the associated vectors are timelike, spacelike or null at each point where the field is defined.

Causality relations

Let x, y ∈ M. We say that

- x chronologically precedes y if y − x is future directed timelike.

- x causally precedes y if y − x is future directed null or future directed timelike

Reversed triangle inequality

If v and w are both future-directed timelike four-vectors, then

where, from the definitions above,

Locally flat spacetime

Strictly speaking, the use of the Minkowski space to describe physical systems over finite distances applies only in systems without significant gravitation. In the case of significant gravitation, spacetime becomes curved and one must abandon special relativity in favor of the full theory of general relativity.

Nevertheless, even in such cases, Minkowski space is still a good description in an infinitesimal region surrounding any point (barring gravitational singularities). More abstractly, we say that in the presence of gravity spacetime is described by a curved 4-dimensional manifold for which the tangent space to any point is a 4-dimensional Minkowski space. Thus, the structure of Minkowski space is still essential in the description of general relativity.

In the realm of weak gravity, spacetime becomes flat and looks globally, not just locally, like Minkowski space. For this reason Minkowski space is often referred to as flat spacetime.

See also

|

References

- ^ *Poincaré, Henri (1905/6), , Rendiconti del Circolo matematico di Palermo, 21: 129–176, doi:10.1007/BF03013466

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)- Wikisource translation: On the Dynamics of the Electron

- ^ Minkowski, Hermann (1907/8), , Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse: 53–111

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)- Wikisource translation: The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies.

- ^ Minkowski, Hermann (1908/9), , Physikalische Zeitschrift, 10: 75–88

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link)- Various English translations on Wikisource: Space and Time

- ^ Failure of subadditivity may be seen in the sum of two nonparallel future-oriented light-like four-vectors having a Minkowski norm greater than the sum of that of each vector.

- Galison P L: Minkowski's Space-Time: from visual thinking to the absolute world, Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences (R McCormach et al. eds) Johns Hopkins Univ.Press, vol.10 1979 85-121

- Corry L: Hermann Minkowski and the postulate of relativity, Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 51 1997 273-314

- Francesco Catoni, Dino Boccaletti, & Roberto Cannata (2008) Mathematics of Minkowski Space, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel.

- Naber, Gregory L. (1992). The Geometry of Minkowski Spacetime. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97848-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Roger Penrose (2005) Road to Reality : A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe, chapter 18 "Minkowskian geometry", Alfred A. Knopf ISBN 9780679454434 .

- Shaw, Ronald (1982) Linear Algebra and Group Representations, § 6.6 "Minkowski space", § 6.7,8 "Canonical forms", pp 221–42, Academic Press ISBN 0-12-639201-3 .

- Walter, Scott (1999). "Minkowski, Mathematicians, and the Mathematical Theory of Relativity". In Goenner, Hubert et al. (ed.) (ed.). The Expanding Worlds of General Relativity. Boston: Birkhäuser. pp. 45–86. ISBN 0-8176-4060-6.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

External links

![]() Media related to Minkowski diagrams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Minkowski diagrams at Wikimedia Commons

- Animation clip on YouTube visualizing Minkowski space in the context of special relativity.