Whistling: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

已添加链接 Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Image:Duveneck Whistling Boy.jpg|thumb|''The Whistling Boy'', [[Frank Duveneck]] (1872)]] |

[[Image:Duveneck Whistling Boy.jpg|thumb|''The Whistling Boy'', [[Frank Duveneck]] (1872)]] |

||

'''Whistling''' without the use of an artificial [[whistle]] is achieved by creating a small opening with one's lips and then blowing or sucking air through the hole. The air is moderated by the lips, curled tongue, teeth or fingers (placed over the mouth) to create [[turbulence]], and the mouth acts as a [[resonance|resonant]] chamber to enhance the resulting sound by acting as a type of [[Helmholtz resonance|Helmholtz resonator]]. |

'''Whistling''' without the use of an artificial [[whistle]] is achieved by creating a small opening with one's lips and then blowing or sucking air through the hole. The air is moderated by the lips, curled tongue<ref>{{cite web|title=How to Whistle With Your Fingers|url=http://www.artofmanliness.com/2012/04/08/how-to-whistle-with-your-fingers/|publisher=[[The Art of Manliness]]|date=April 8, 2012|accessdate=March 7, 2017}}</ref>, teeth or fingers (placed over the mouth) to create [[turbulence]], and the mouth acts as a [[resonance|resonant]] chamber to enhance the resulting sound by acting as a type of [[Helmholtz resonance|Helmholtz resonator]]. |

||

==Techniques== |

==Techniques== |

||

Revision as of 17:23, 7 March 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2012) |

Whistling without the use of an artificial whistle is achieved by creating a small opening with one's lips and then blowing or sucking air through the hole. The air is moderated by the lips, curled tongue[1], teeth or fingers (placed over the mouth) to create turbulence, and the mouth acts as a resonant chamber to enhance the resulting sound by acting as a type of Helmholtz resonator.

Techniques

Pucker whistling is the most common form in much Western music. Typically, the tongue tip is lowered, often placed behind the lower teeth, and pitch altered by varying the position of the tongue. In particular, the point at which the tongue body approximates the palate varies from near the uvula (for low notes) to near the alveolar ridge (for high notes). Although varying the degree of pucker will change the pitch of a pucker whistle, expert pucker whistlers will generally only make small variations to the degree of pucker, due to its tendency to affect purity of tone. Pucker whistling can be done by either only blowing out or blowing in and out alternately. In the 'only blow out' method, a consistent tone is achieved, but a negligible pause has to be taken to breathe in. In the alternating method there is no problem of breathlessness or interruption as breath is taken when one whistles breathing in, but a disadvantage is that many times, the consistency of tone is not maintained, and it fluctuates.

Many expert musical palatal whistlers will substantially alter the position of the lips to ensure a good quality tone. Venetian gondoliers are famous for moving the lips while they whistle in a way that can look like singing. A good example of a palatal whistler is Luke Janssen, winner of the 2009 world whistling competition.[2]

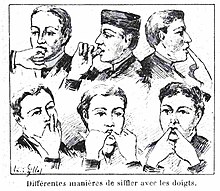

Finger whistling or wolf-whistling is harder to control but achieves a piercing volume. In Boito's opera Mefistofele the title character uses it to expess his defiance of the Almighty.

Whistling can also be produced by blowing air through enclosed, cupped hands or through an external instrument, such as a whistle or even a blade of grass or leaf.

Competitions

One of the most well known whistling competitions is the International Whistlers Convention (IWC). Since 1973, this annual event takes place in Louisburg, North Carolina. The awards go to whistlers ranging from international male and female, teenage male and female, and even grandchildren. It has been customary for the Governor of the State of North Carolina to sign a declaration declaring the week of the IWC as "Happy Whistlers Week," for citizens and visitors to honor the art of whistling and to participate in the scheduled events.[3]

According to Guinness World Records, the highest pitch human whistle ever recorded was measured at 4,186 Hz, which corresponds to a C8 musical note. This was done by Michael Stuart in Richmond, Virginia, USA on January 11, 2016.[4] The lowest pitch whistle ever recorded was measured at 174.6 Hz, which corresponds to a F3 musical note. This was accomplished by Jennifer Davies of Dachau, Germany on November 6, 2005.[5] The most people whistling simultaneously was 853, which was organized at the Spring Harvest event at Minehead, UK on April 11, 2014.[6]

As communication

On La Gomera, one of Spain's Canary Islands, a traditional whistled language named Silbo Gomero is still used. Six separate whistling sounds are used to produce two vowels and four consonants, allowing this language to convey more than 4000 words. This language allowed people (e.g. shepherds) to communicate over long distances in the island, when other communication means were not available. It is now taught in school so that it is not lost among the younger generation. Another group of whistlers were the Mazateco Indians of Oaxaca, Mexico. Their whistling aided in conveying messages over far distances, but was also used in close quarters as a unique form of communication with a variety of tones.[7]

Whistling can be used to control trained animals such as dogs. A Shepherd's whistle is often used instead.

Whistling has long been used as a specialized communication between laborers. For example, whistling in theatre, particularly on-stage, is used by flymen (i.e. members of a fly crew) to cue the lowering or raising of a batten pipe or flat. This method of communication became popular before the invention of electronic means of communication, and is still in use, primarily in older "hemp" houses during the set and strike of a show.[8][9]

In music

The range of pucker whistlers varies from about one to three octaves. Agnes Woodward [10] classifies by analogy to voice types: soprano (c"-c""), mezzo (a-g'") and alto (e or d-g")[11]

Many performers on the music hall and Vaudeville circuits were professional whistlers, the most famous of which were Ronnie Ronalde and Fred Lowery. The term puccalo or puccolo was coined by Ron McCroby to refer to highly skilled jazz whistling.[12]

Whistling is featured in a number of television themes, such as Lassie, The Andy Griffith Show and Mark Snow's title theme for The X-Files.[13] It also prominently features in the score of the movie Twisted Nerve, composed by Bernard Herrmann, which was later used in Quentin Tarantino's Kill Bill.

Prominent in classic songs such as Bobby McFerrin's "Don't Worry, Be Happy" and Scorpions' "Wind of Change", whistling has also been integrated in many contemporary pop hits such as Flo Rida's "Whistle", Selena Gomez's "Kill Em With Kindness", Florida Georgia Line's "Sun Daze", Foster the People's "Pumped Up Kicks", Maroon 5's "Moves Like Jagger", Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeros' "Home", OneRepublic's "Good Life", Adam Lambert's "Ghost Town", Kanye West's "All Day", and Peter Bjorn and John's "Young Folks".

By spectators

Whistling is often used by spectators at sporting events to expess either enthusiasm or disapprobation. In the United States and Canada, whistling is used much like applause, to express approval or appreciation for the efforts of a team or a player, such as a starting pitcher in baseball who is taken out of the game after having pitched well. In much of the rest of the world, especially Europe and South America, whistling is used to express displeasure with the action or disagreement with an official's decision, like booing. This whistling is often loud and cacophonous, using finger whistling.

Superstitions

In many cultures, whistling or making whistling noises at night is thought to attract bad luck, bad things, or evil spirits.[14][15][16][17]

In the UK there is a superstitious belief in the "Seven Whistlers" which are seven mysterious birds or spirits who call out to foretell death or a great calamity. In the 19th century, large groups of coal miners were known to have refused to enter the mines for one day after hearing this spectral whistling. The Seven Whistlers have been mentioned in literature such as The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser, as bearing an omen of death. William Wordsworth included fear of the Seven Whistlers in his poem, "Though Narrow Be That Old Man's Cares". The superstition has been reported in the Midland Counties of England but also in Lancashire, Essex, Kent, and even in other places such as North Wales and Portugal.[18][19][20][21]

In Russian and other Slavic cultures (also in Romania and the Baltic states), whistling indoors is superstitiously believed to bring poverty ("whistling money away"), whereas whistling outdoors is considered normal. In Estonia it is also widely believed that whistling indoors may bring bad luck and therefore set the house on fire.[22]

Whistling on board a sailing ship is thought to encourage the wind strength to increase.[23] This is regularly alluded to in the Aubrey-Maturin books by Patrick O'Brian.

Theater practice has plenty of superstitions: one of them is against whistling. A popular explanation is that traditionally sailors, skilled in rigging and accustomed to the boatswain's pipe, were often used as stage technicians, working with the complicated rope systems associated with flying. An errant whistle might cause a cue to come early or a "sailor's ghost" to drop a set-piece on top of an actor. An offstage whistle audible to the audience in the middle of a performance might also be considered bad luck.

Transcendental whistling (changxiao 長嘯) was an ancient Chinese Daoist technique of resounding breath yoga, and skillful whistlers supposedly could summon supernatural beings, wild animals, and weather phenomena.

Children's television cartoon shows

See also

References

- ^ "How to Whistle With Your Fingers". The Art of Manliness. April 8, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ Jessica Satherly (April 28, 2009). "King of whistles challenges Boyle for top talent". Metro (British newspaper).

- ^ "IWC Main Website".

- ^ "Guinness World Records, Highest note whistled".

- ^ "Guinness World Records, Lowest note whistled".

- ^ "Guinness World Records, Most people whistling".

- ^ Busnel & Classe 1976

- ^ Hughes, Maureen. A History of Pantomime, p. 31 (2013).

- ^ Asbury, Nick. Exit Pursued by a Badger: An Actor's Journey Through History with Shakespeare, p. 134 (Oberon Books 2009).

- ^ Woodward, Agnes: Whistling as an Art (Carl Fischer, New York 1923)

- ^ Page x. These are written pitches, presumably sounding an octave higher and corresponding to C5-C7 &c

- ^ Sheff, David. "They Laughed When Ron McCroby Puckered Up, but Now He's Whistlin' Jazz, Not Dixie", People (August 8, 1983).

- ^ Snow called it the "signature whistle" that gave the music part of its "scariness". Greiving, Tim (January 22, 2016). "As 'X-Files' Returns, Meet The Man Behind The Theme Song". NPR. Retrieved January 23, 2016.

- ^ Tate (June 30, 2009). "Things Fall Apart – Ch 2". Washington State School for the Blind. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Daily Traditions". Fantastic Asia Ltd. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ "Belide Tribe 22.000". Indonesia Traveling. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ GaboudAchk (January 24, 2009). "Evil Eye...... Growing Up". Experience Project. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ^ Wright, Elizabeth Mary (1913). Rustic speech and folk-lore. H. Milford. p. 197.

- ^ William Knight, ed. (1883). The poetical works of William Wordsworth. Vol. 4. Edinburgh: William Paterson. pp. 73–76.

- ^ "Notes and Queries, Fifth series". 2. London: Oxford Journals, Oxford University. October 3, 1874: 264.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Taylor, Archer (April 1917). "Three Birds of Ill Omen in British Folklore – III. The Seven Whistlers". Washington University Studies. IV (2). St Louis, Missouri: Washington University: 167–173.

- ^ Passport magazine article

- ^ Gonzalez, N. V. M. "Whistling Up the Wind: Myth and Creativity." Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 31.2 (1983): 216–226.

External links

- Stekelenburg, A.V. van. "Whistling in Antiquity", Akroterion, vol. 45, pp. 65–74 (2000).

- Kahn, Ric. "Finally, whistling is cool again", Boston Globe, August 27, 2007

- Alexandra Petri. "Not just anyone can whistle, at the 2013 International Whistling Convention", Washington Post (April 29, 2013).

- Casey, Liam. "Toronto whistler blows past the competition at international contest", Toronto Star (May 3, 2013).

- International Whistlers Museum in Louisburg, North Carolina

- Indian Whistlers Association (IWA)

- Professional whistler Dave Santucci provides whistling performance videos and whistling tutorial videos (YouTube)

- "History of Musical Whistling" given by Linda Parker Hamilton at the 2012 International Whistlers Convention (YouTube)

- Northern Nightingale site with whistling lessons and links to other whistlers' sites

- Biography page of whistling performer Robert Stemmons with links to other whistlers' sites