Madam C. J. Walker: Difference between revisions

× Close Ad People Nostalgia Celebrity History & Culture Famous Lookalikes Crime & Scandal Video About Contact Us Advertise Privacy Terms of Use Copyright Policy Ad Choices People Nostalgia Celebrity History & Culture Black History Crime & Scand |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 73.172.46.75 to version by Boomer Vial. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (3266179) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox person |

|||

| name = Madam C. J. Walker |

|||

| birth_name = Sarah Breedlove |

|||

| image = Madam CJ Walker face circa 1914.jpg |

|||

| caption = Walker in 1903 |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1867|12|23|mf=y}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Delta, Louisiana]], United States |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1919|5|25|1867|12|23|mf=y}} |

|||

| death_place = {{Nowrap|[[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]], United States}} |

|||

| resting_place =[[Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)]] |

|||

| resting_place_coordinates = <!-- {{Coord|LAT|LONG|type:landmark|display=inline}} --> |

|||

| monuments = |

|||

| residence=[[Villa Lewaro]], Irvington-on-Hudson, New York |

|||

| nationality = American |

|||

| other_names = |

|||

| education = |

|||

| occupation= [[businessperson|Businesswoman]], [[hair care|hair-care]] entrepreneur,<br/>[[Philanthropy|Philanthropist]], and<br />[[Activism|Activist]] |

|||

| known_for = |

|||

| home_town = |

|||

| net_worth = <!-- Net worth should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

|||

| height = <!-- {{height|m=}} --> |

|||

| weight = <!-- {{convert|weight in kg|kg|lb}} --> |

|||

| party = |

|||

| boards = |

|||

| religion = <!-- Religion should be supported with a citation from a reliable source --> |

|||

| spouse=Moses McWilliams (married 1882–1887)<br/>John Davis (married 1894 – c. 1903)<br/>Charles Joseph Walker (married 1906–1912) |

|||

| children = [[A'Lelia Walker]] |

|||

| relatives = |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| signature = |

|||

| signature_alt = |

|||

| signature_size = |

|||

| website ={{URL|www.madamcjwalker.com}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:MadameCJWalkerdrivingautomoblie.png|thumb|right|Madam Walker and several friends in her automobile]] |

|||

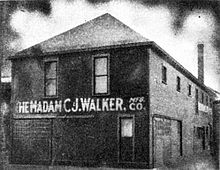

[[File:Madam CJ Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, Indiana (1911).jpg|thumb|right|C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company, Indianapolis, 1911]] |

|||

'''Sarah Breedlove''' (December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919), known as '''Madam C. J. Walker''', was an African American [[entrepreneur]], [[philanthropist]], and a political and social [[Activism|activist]]. Eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America,<ref name="Philanthropy"/> she became one of the wealthiest African American women in the country, "the world's most successful female entrepreneur of her time," and one of the most successful [[African-American businesses|African-American business]] owners ever.<ref>{{cite triumph|page=75}}</ref> |

|||

× Close Ad |

|||

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women through [[Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company]], the successful business she founded. Walker was also known for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. [[Villa Lewaro]], Walker’s lavish estate in [[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]], served as a social gathering place for the African American community. |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near [[Delta, Louisiana]], to Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove.<ref name=BWA1209>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1209.</ref><ref name=Bundles-website>{{cite web|last1=Bundles|first1=A’Lelia|title=Madam C.J. Walker |url = http://www.madamcjwalker.com/bios/madam-c-j-walker/ |website=Madame C.J. Walker|accessdate=25 February 2015}}</ref> Sarah was one of six children, which included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Breedlove's parents and her older siblings were enslaved on Robert W. Burney's Madison Parish plantation, but Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the [[Emancipation Proclamation]] was signed. Her mother died, possibly from [[cholera]], in 1872; her father remarried, but he died within a few years.{{citation needed|date=February 2016}} Orphaned at the age of seven, Sarah moved to [[Vicksburg, Mississippi]], at the age of ten and worked as a domestic. Prior to her first marriage, she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.<ref name=BWA1209/><ref name=indiana-history>{{cite web|title=Madam C. J. Walker |url = http://www.indianahistory.org/our-collections/reference/notable-hoosiers/madam-c.j.-walker#.VPIQUlPF_0p |publisher=[[Indiana Historical Society]]|accessdate=2015-02-28 }}</ref> |

|||

==Marriage and family== |

|||

In 1882, at the age of fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, possibly to escape mistreatment from her brother-in-law.<ref name=BWA1209/> Sarah and Moses had one daughter, [[A'Lelia Walker|Lelia McWilliams]], born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty; Lelia was two years old.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=NC100Bio>{{cite web | author=A'lelia Bundles| title =Biography of Madam C. J. Walker | work = | publisher =National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter | date =2014 |url= http://www.onehundredblackwomen.com/madame-c-j-walker/ | format = | accessdate =2016-02-05}}</ref> Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903 and moved to [[Denver]], [[Colorado]], in 1905.<ref name=GS360>{{cite book | author= Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. | title = Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State | publisher =Indiana Historical Society Press| year =2015 | location =Indianapolis | page =360 | url = | isbn =978-0-87195-387-2}}</ref><ref name="PhilanthropyX">{{cite web|title=The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Madam C. J. Walker |url= |

|||

http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/hall_of_fame/madam_c._j._walker |publisher=Philanthropy Roundtable|accessdate=2015-03-01}}</ref> |

|||

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in [[Missouri]]. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather's surname and became known as [[A'Lelia Walker]].<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=BWA1210-11>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, pp. 1210–11.</ref><ref name=Riquier>{{cite web| author =Andrea Riquier | title =Madam Walker Went from Laundress to Success | publisher=Investor's Business Daily | date =2015-02-24| url = http://news.investors.com/management-leaders-and-success/022415-740635-madam-walker-built-hair-care-empire-rose-from-washerwoman.htm|accessdate =2016-02-08}}</ref> |

|||

==Career== |

|||

People |

|||

In 1888 Sarah and her daughter moved to [[St. Louis|Saint Louis]], Missouri, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, barely earning more than a dollar a day, but she was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with a formal education.<ref name=bundles /><ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.biography.com/people/madam-cj-walker-9522174#early-entrepreneurship|title = Madam C.J. Walker Biography|date = |accessdate =2016-02-15 |website =Biography.com |publisher = A&E Television Networks|author= Editors}}</ref> During the 1880s, Breedlove lived in a community where [[Ragtime|ragtime music]] was developed—she sang at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church.<ref name="Philanthropy" /> As was common among black women of her era, Sarah experienced severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products such as [[lye]] that were included in soaps to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating and electricity.<ref name=Riquier/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001">{{cite book | author=A'Lelia Bundles| title=On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C. J. Walker| publisher=Scribner |location=New York |

|||

Nostalgia |

|||

|year=2001| pages = | url = | isbn =0-7434-3172-3}}</ref><ref name=ingham>{{cite web | author=John N. Ingham|title =Madame C. J. Walker |publisher=American National Biography Online| date=February 2000 |url = | accessdate=}} (subscription required)</ref> |

|||

Celebrity |

|||

History & Culture |

|||

Famous Lookalikes |

|||

Crime & Scandal |

|||

Video |

|||

About |

|||

Contact Us |

|||

Advertise |

|||

Privacy |

|||

Terms of Use |

|||

Copyright Policy |

|||

Ad Choices |

|||

[[File:The Childrens Museum of Indianapolis - Madame C.J. Walkers Wonderful Hair Grower.jpg|thumb|right|alt=A container of Madame C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower is held in the permanent collection of [[The Children's Museum of Indianapolis]].|Madame C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower in the permanent collection of [[The Children's Museum of Indianapolis]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Madam C.J. Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower product container|url=http://digitallibrary.imcpl.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tcm/id/168|publisher=The Indianapolis Public Library|accessdate=2 March 2015}}</ref>]] |

|||

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in Saint Louis.<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> Around the time of the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]] (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for [[Annie Malone|Annie Turnbo Malone]], an African American hair-care entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company.<ref name=BWA1209/> While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry,<ref name="Philanthropy" /> Sarah began to adapt her knowledge of hair and hair products to develop her own product line.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> |

|||

In July 1905, when she was thirty-seven years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to [[Denver]], [[Colorado]], where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker and marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.<ref name=Success />) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=BWA1210-11/> |

|||

In 1906 Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.<ref name=bundles>{{cite journal|author=A'Lelia Bundles |title=Madam C.J. Walker: Business Savvy to Philanthropy|journal=eJournal USA|date=February 2012|volume=16|issue=6|pages=3–5|url=https://photos.state.gov/libraries/amgov/30145/publications-english/Black_Women_Leaders_eJ.pdf|accessdate=2015-03-01|publisher=U.S. Department of State}}</ref><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/><ref name=ingham/><ref>{{cite book |author1=Harold Evans |author2=Gail Buckland |author3=David Lefer |last-author-amp=yes | title=They Made America: From the Steam Engine to the Search Engine: Two Centuries of Innovators| location =New York| publisher=Little, Brown| year=2004| page = | url = | isbn =9780316277662 }}</ref> In 1908 Walker and her husband relocated to [[Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania]], where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train "hair culturists." After closing the business in Denver in 1907, A'lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh, while Walker established a new base in [[Indianapolis]] in 1910.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Nancy F. Koehn |author2=Anne E. Dwojeski |author3=William Grundy |author4=Erica Helms |author5=Katherine Miller | title = Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur, Leader, and Philanthropist | publisher =Harvard Business School Publishing | series = | volume =9-807-145 | edition = | year =2007 | location =Boston | page =12 | url = | OCLC=154317207}}</ref> A'lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in [[New York City]]'s [[Harlem]] neighborhood in 1913.<ref name=Success>{{cite web |author= A'Lelia Bundles|title=Madam C. J. Walker’s Secrets to Success |publisher=Biography.com| date= |url =http://www.biography.com/news/madam-cj-walker-biography-facts |accessdate=2016-02-09}}</ref> |

|||

In 1910 Walker relocated her business to [[Indianapolis]], where she established the headquarters for the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street.<ref name=GS361>Gugin and Saint Clair, p. 361.</ref> Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research.<ref name=ingham/> She also assembled a competent staff that included [[Freeman Ransom]], [[Robert Lee Brokenburr]], [[Alice Kelly]], and [[Marjorie Joyner|Marjorie Stewart Joyner]], among others, to assist in managing the growing company.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> Many of her company's employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.<ref name=Success/> |

|||

To increase her company's sales force, Walker trained other women to become "beauty culturists" using "The Walker System", her method of grooming that was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products.<ref name=BWA1210-11/> Walker's system included a [[shampoo]], a [[pomade]] stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxurious.<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> Walker's product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone's Poro System and later, Sarah Spencer Washington's Apex System.<ref name=Science/> |

|||

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products.<ref name=indiana-history/> By 1917 the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women.<ref name=GS361/> Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the [[Caribbean]] offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker's frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States. Walker's name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company's business market expanded beyond the United States to [[Cuba]], [[Jamaica]], [[Haiti]], [[Panama]], and [[Costa Rica]].<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/><ref name=Success/><ref name=Science>{{cite web| title=Madame C. J. Walker (Sarah Breedlove McWilliams Walker): Inventor, Businesswoman|work=The Faces of Science: African Americans in the Sciences|publisher=| date= |url = https://webfiles.uci.edu/mcbrown/display/walker.html |accessdate=2015-05-22}}</ref> |

|||

People |

|||

Nostalgia |

|||

Celebrity |

|||

History & Culture |

|||

Black History |

|||

Crime & Scandal |

|||

Video |

|||

Hip Hop |

|||

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the [[National Association of Colored Women]], Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America).<ref name=indiana-history/> Its first annual conference convened in [[Philadelphia]] during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce.<ref name=Riquier/><ref name=bundles /> During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.<ref name=bundles/> |

|||

==Activism and philanthropy== |

|||

[[File:Madam CJ Walker home 67 Broadway Irvington NY jeh.jpg|thumb|House in Irvington]] |

|||

As Walker's wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912 Walker addressed an annual gathering of the [[National Negro Business League]] (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.<ref name=GS361/>" The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.<ref name=bundles/><ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the [[YMCA|Young Men’s Christian Association]] (YMCA) in Indianapolis's black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for the Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the [[Tuskegee University|Tuskegee Institute]]. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and [[Bethel A.M.E. Church (Indianapolis, Indiana)|Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church]]; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became [[Bethune-Cookman University]]) in [[Daytona Beach, Florida]]; the [[Palmer Memorial Institute]] in [[North Carolina]]; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]]. Walker was also a patron of the arts.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=bundles/> |

|||

About 1913 Walker's daughter, A'Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916 Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis.<ref name=Bundles-website/><ref name=GS361/> In 1917 Walker commissioned [[Vertner Tandy]], the first licensed black architect in [[New York City]] and a founding member of [[Alpha Phi Alpha]] fraternity, to design her house in [[Irvington-on-Hudson, New York]]. Walker intended for [[Villa Lewaro]], which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams.<ref name=Science/><ref>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1213.</ref><ref name=TimesObit>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1223.html |title =Wealthiest Negress Dead |work=[[New York Times]] |date=May 26, 1919 |accessdate=2015-03-01}}</ref> She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor [[Emmett Jay Scott]], at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the [[United States War Department|U.S. Department of War]].<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included [[Booker T. Washington]], [[Mary McLeod Bethune]], and [[W. E. B. Du Bois]].<ref name=indiana-history/> During [[World War I]] Walker was a leader in the [[Circle For Negro War Relief]] and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers.<ref name=GS361/> In 1917 she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP), which organized the [[Silent Parade|Silent Protest Parade]] on New York City's Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed thirty-nine African Americans.<ref name=bundles/> |

|||

Subscribe to NewsletterAbout |

|||

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker's contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918 the [[National Association of Colored Women's Clubs]] (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve [[Frederick Douglass]]’s [[Anacostia]] house.<ref>Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in ''Black Women in America'', v. II, p. 1212.</ref> Prior to her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012) to the NAACP's anti-[[lynching]] fund. At the time it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity.<ref name=Philanthropy>{{cite web|title=Madam C. J. Walker |url =http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/hall_of_fame/madam_c._j._walker|website=The Philanthropy Hall of Fame|publisher=Philanthropy Roundtable|accessdate=1 March 2015}}</ref><ref name=bundles/><ref name=Success/> |

|||

[[File:Madam C. J. Walker Grave 2009.JPG|thumb|right|The grave of Madam C. J. Walker]] |

|||

==Death and legacy== |

|||

Biography |

|||

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of [[hypertension]] at the age of fifty-one.<ref name=indiana-history/><ref name=GS361/><ref name=TimesObit/> Walker's remains are interred in [[Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)|Woodlawn Cemetery]] in [[The Bronx]], New York City.<ref>{{cite web| title =Woodlawn Cemetery–Madam Walker’s Burial Place–Named National Historic Landmark |url=https://madamcjwalker.wordpress.com/tag/woodlawn-cemetery/ | work = | publisher = | date = | accessdate =2016-02-02}}</ref> |

|||

Gandhi: A Legacy of Peace |

|||

At the time of her death Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in America. She was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, but Walker's estate was only worth an estimated $600,000 (approximately $8 million in present-day dollars) upon her death.<ref name="Philanthropy"/> According to Walker's ''New York Times'' obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time."<ref name=TimesObit /> At the time of Walker's death, the average American's annual salary was $750.<ref>https://bizfluent.com/info-7769323-history-american-income.html</ref> Her daughter, [[A'Lelia Walker]], became the president of the [[Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company]].<ref name="Her Own Ground 2001"/> |

|||

HAPPY BIRTHDAY |

|||

Christian Bale |

|||

Walker's personal papers are preserved at the [[Indiana Historical Society]] in Indianapolis.<ref name=Riquier/> Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]]: [[Villa Lewaro]] in [[Irvington, New York]], and the [[Madame Walker Theatre Center]] in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A'Lelia Walker's death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the [[National Register of Historic Places]] in 1979. The [[National Trust for Historic Preservation]] has designated the privately owned property a National Treasure.<ref>{{cite web| author=Jessica Pumphrey | title =Sign the Pledge to Protect Villa Lewaro – And Learn How You Can Tour It | work = | publisher =National Trust for Historic Preservation | date =2014-10-24 | url = https://savingplaces.org/stories/pledge-protect-villa-lewaro-get-tour#.VrT4TWBEg2w | format = | accessdate =2016-02-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite web| author=Brent Leggs| |

|||

url=http://www.preservationnation.org/assets/pdfs/saving-places/Preserving-Villa-Lewaro-National-Treasure-Madam-C-J-Walker-Estate.pdf| title =Envisioning Villa Lewaro's Future| publisher=[[National Trust for Historic Preservation]]| date=2014|accessdate =2016-02-19}}</ref> Indianapolis's Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theatre Center, opened in December 1927; it included the company's offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.<ref name=Success/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://focus.nps.gov/AssetDetail/NRIS/80000062 |title=National Register Digital Assets: Madame C. J. Walker Building |date= |publisher=National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior}}</ref> |

|||

In 2006, playwright and director [[Regina Taylor]] wrote The ''Dreams of Sarah Breedlove,'' recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success.<ref name=":0">"Regina Taylor Brings the Story of Madam C.J. Walker to the Stage." Jet Jul 10 2006: 62-3. ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .</ref> The play premiered at the [[Goodman Theatre|Goodman Theater]] in Chicago.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.goodmantheatre.org/season/0506/the-dreams-of-sarah-breedlove/|title=The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove {{!}} Goodman Theater {{!}} Chicago|website=www.goodmantheatre.org|access-date=2016-03-06}}</ref> Actress [[L. Scott Caldwell]] played the role of Walker.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

People |

|||

Nostalgia |

|||

Celebrity |

|||

History & Culture |

|||

Black History |

|||

Crime & Scandal |

|||

Video |

|||

Hip Hop |

|||

On March 4, 2016, skincare and haircare company Sundial Brands launched a collaboration with [[Sephora]] in honor of Walker’s legacy. The launch, titled “Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture”, comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.<ref>"Sundial Brands Enters Prestige Hair Category with Historic Launch of Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture Exclusively at Sephora." PR Newswire Feb 23 2016ProQuest. 6 Mar. 2016 .</ref> As of 2017, actress [[Octavia Spencer]] has committed to portray Walker in a TV series based on the biography of Walker by A’Lelia Bundles, Walker's great-great-granddaughter.<ref name=nypost>Lanert, Raquel (February 18, 2017) [https://nypost.com/2017/02/18/manse-built-by-americas-first-self-made-millionairess-in-jeopardy/ "Manse built by America’s first self-made millionairess in jeopardy"] ''[[New York Post]]''</ref> |

|||

==Tributes== |

|||

Home |

|||

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker's honour: |

|||

* The Madam C. J Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the [[National Coalition of 100 Black Women]], Oakland/Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honours Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.<ref>{{cite web|title=17th Annual Madam C. J. Walker 2015 Luncheon |url= |

|||

http://www.onehundredblackwomen.com/madame-c-j-walker/17th-annual-mcjw-2015-luncheon/|publisher=National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter|accessdate=2016-02-05}}</ref> |

|||

* Spirit Awards have sponsored the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual awards have honoured national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.<ref name=awards>{{cite web | title=About the Spirit Awards | url=http://www.thewalkertheatre.org/spirit-awards/nomination-form | publisher=Madame Walker Theatre Center | year=2016 | accessdate=2016-02-04}}</ref> |

|||

Walker was inducted into the [[National Women's Hall of Fame]] in [[Seneca, New York]], in 1993.<ref>{{cite web| title =Madam C. J. Walker | work = | publisher =National Women’s Hall of Fame | date = | url = https://www.womenofthehall.org/inductee/madam-c-j-walker/| format = | accessdate =2016-02-10}}</ref> In 1998 the [[United States Postal Service|U.S. Postal Service]] issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.<ref name=GS361/><ref>[http://www.usstampgallery.com/view.php?id=76b046e9928ba079d703ec17fae2813be2625b64&Madam_CJ_Walker&st=madame%20walker&ss=&t=&s=4&syear=&eyear= US Stamp Gallery]</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

'''Nonfiction biographies''' (based on primary source documents) |

|||

*{{cite book| author=[[A'Lelia Bundles|Bundles, A'Lelia Perry]]| title =Madam Walker Theatre Center: An Indianapolis Treasure |publisher =Arcadia Publishing| series =Images of America | volume = | edition = |year=2013 |location =Charleston, SC |isbn=1-4671-1087-6}} |

|||

*{{cite book| author=Bundles, A'Lelia Perry|title=Madam C. J. Walker: Entrepreneur |publisher=Chelsea House| series =Black Americans of Achievement | volume = | edition =Legacy |year=2008| location =New York | isbn=978-1-60413-072-0}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=[[Penny Colman|Colman, Penny]] | title =Madam C. J. Walker: Building a Business Empire |publisher=The Millbrook Press | series =Gateway Biography | volume = | edition = | year =1994 |location =Brookfield, CT | pages = | url = | isbn =9781562943387}} |

|||

*{{cite book|editor1-last=Sullivan|editor1-first=Otha Richard|editor2-last=Haskins|editor2-first=James| editor2link =James Haskins|title=African American Women Scientists and Inventors|date=2002|publisher=Jossey-Bass|location=San Francisco|isbn=9780471387077|pages=25-30|chapter=Madam C.J. Walker (1867–1919)}} |

|||

'''Fiction/novels''' |

|||

*{{cite book| author=[[Tananarive Due|Due, Tananarive]] |title=The Black Rose: The Dramatic Story of Madam C. J. Walker, America's First Black Female Millionaire |publisher=Ballantine Books |year=2000|isbn=0-345-44156-7}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

Quick Facts |

|||

*{{Findagrave|18239}} |

|||

Name |

|||

*{{YouTube|AuYjx7zDBas|Madam C J Walker-Successful Business Woman}} |

|||

Michael Jackson |

|||

*{{YouTube|Kk-17lfCeGs|Stanley Nelson Interviews Madam C. J. Walker's Great Grand Daughter}} (Walker's political activism and philanthropy) |

|||

Occupation |

|||

*{{cite video| people = | title =On Her Own Ground: Madame C. J. Walker | medium = | publisher =C-Span| location = | date =2001-01-27 | url=http://www.c-spanvideo.org/program/CJ}} (Book discussion) |

|||

Dancer, Songwriter, Singer, Music Producer |

|||

*{{YouTube|p3qjlLYszEI|Madam Walker Research in the National Archives}} |

|||

Birth Date |

|||

*{{YouTube|-O4BGrMcD4o|The Legacy of Madam Walker}} (Part 1) |

|||

August 29, 1958 |

|||

*{{YouTube|2lXl8XKfZ-8|Madam C J Walker}} (Indiana Bicentennial Minute, 2016) |

|||

Death Date |

|||

*{{YouTube|n4knvT_-IO8|Madam C J Walker Estate}} (Part 1 of 5) Villa Lewaro, Irvington-on-Hudson, New York |

|||

June 25, 2009 |

|||

Did You Know? |

|||

Michael Jackson was one of nine children. |

|||

Did You Know? |

|||

Jackson joined the Jackson 5 when he was only five years old. |

|||

Did You Know? |

|||

'Thriller' is the best-selling music album of all time. |

|||

Did You Know? |

|||

The 'This Is It' movie became the highest grossing concert film of all time. |

|||

Place of Birth |

|||

Gary, Indiana |

|||

Place of Death |

|||

Los Angeles, California |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

Who Was Michael Jackson? |

|||

Michael Jackson Solo Albums |

|||

Videos |

|||

Related Videos |

|||

Cite This Page |

|||

IN THESE GROUPS |

|||

The Jackson Family |

|||

Famous People Who Died on June 25 |

|||

Famous Dancers |

|||

Famous People Who Overdosed |

|||

Show All Groups |

|||

1 of 11« » |

|||

quotes |

|||

“Being onstage is magic. There's nothing like it. You feel the energy of everybody who's out there. You feel it all over your body.” |

|||

—Michael Jackson |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Walker, Madam C. J.}} |

|||

Michael Jackson Biography |

|||

[[Category:Madam C. J. Walker| ]] |

|||

Dancer, Songwriter, Singer, Music Producer(1958–2009) |

|||

[[Category:1867 births]] |

|||

54.8K |

|||

[[Category:1919 deaths]] |

|||

SHARES |

|||

[[Category:American philanthropists]] |

|||

[[Category:American millionaires]] |

|||

[[Category:American women in business]] |

|||

[[Category:Businesspeople from Louisiana]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American company founders]] |

|||

[[Category:American company founders]] |

|||

Michael Jackson enjoyed a chart-topping career both with the Jackson 5 and as a solo artist. He released the best-selling album in history, 'Thriller,' in 1982. |

|||

[[Category:Deaths from hypertension]] |

|||

Who Was Michael Jackson? |

|||

[[Category:People from Madison Parish, Louisiana]] |

|||

Known as the "King of Pop," Michael Joseph Jackson (August 29, 1958 to June 25, 2009) was a best-selling American singer, songwriter and dancer. As a child, Jackson became the lead singer of his family's popular Motown group, the Jackson 5. He went on to a solo career of astonishing worldwide success, delivering No. 1 hits from the albums Off the Wall, Thriller and Bad. In his later years, Jackson was dogged by allegations of child molestation. He died of a drug overdose just before launching a comeback tour in 2009. |

|||

[[Category:People from St. Louis]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Denver]] |

|||

25 |

|||

[[Category:People from Indianapolis]] |

|||

Gallery |

|||

[[Category:People from Irvington, New York]] |

|||

25 Images |

|||

[[Category:Beauticians]] |

|||

Michael Jackson Solo Albums |

|||

'Got to Be There' (1971) |

|||

At the age of 13, Jackson launched a solo career in addition to his work with the Jackson 5, making the charts in 1971 with "Got to Be There," from the album of the same name. |

|||

'Ben' (1972) |

|||

Jackson’s 1972 album, Ben, featured the eponymous ballad about a rat. The song became Jackson's first solo No. 1 single. |

|||

'Music and Me' (1973) |

|||

Michael's third solo album, Music and Me was his least successful. |

|||

'Forever, Michael' (1975) |

|||

This fourth solo album for Michael was his last with Motown records. |

|||

'Off the Wall' (1979) |

|||

An infectious blend of pop and funk, Michael wowed the music world with 1979’s Off the Wall, which featured the Grammy Award-winning single "Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough," along with such hits as "Rock with You," "She's Out of My Life" and the title track. |

|||

'Thriller' (1982) |

|||

Released in 1982, Michael Jackson’s sixth solo album Thriller is the best-selling album in history, generating seven Top 10 hits. The album stayed on the charts for 80 weeks, holding the No. 1 spot for 37 weeks. In addition to its unparalleled commercial achievements, Thriller garnered 12 Grammy Award nominations and notched eight wins, both records. Jackson's victories showcased the diverse nature of his work. For his songwriting talents, he earned a Grammy (best rhythm and blues song) for "Billie Jean." He also was honored for the singles "Thriller" (best pop vocal performance, male) and "Beat It" (best rock vocal performance, male). With co-producer Quincy Jones, Jackson shared the award for album of the year. |

|||

For this album, Jackson teamed up with rock legend Paul McCartney for their 1982 duet, "The Girl Is Mine," which nearly reached the top of the pop charts. His most elaborate music video was for the album's title track. John Landis directed the horror-tinged video, which featured complex dance scenes, special effects and a voice-over by actor Vincent Price. The "Thriller" video was an immense success, boosting sales for the already successful record. |

|||

'We Are the World' (single, 1985) |

|||

In 1985, Jackson showed his altruistic side by co-writing "We Are the World," a charity single for USA for Africa. A veritable who's who of music stars participated in the project, including Lionel Richie, Ray Charles, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Bruce Springsteen and Tina Turner. |

|||

'Bad' (1987) |

|||

Michael Jackson’s album Bad (1987), released as a follow-up to Thriller, reached the top of the charts, with a record five No. 1 hits, including "Man in the Mirror," "The Way You Make Me Feel" and the title track, which was supported by a video directed by Martin Scorsese. Jackson spent more than a year on the road, playing concerts to promote the album. While highly successful, Bad was unable to duplicate the phenomenal sales of Thriller. |

|||

'Dangerous' (1991) |

|||

In 1991, Jackson released Dangerous, featuring the hit "Black or White." The video for this song, directed by Landis, included an appearance by child star Macaulay Culkin. In the video's final minutes, Jackson caused some controversy with his sexual gesturing and violent actions. Many were surprised to see the Peter Pan-like Jackson act in this manner. Jackson's music continued to enjoy widespread popularity in the following years. In 1993, he performed at several important events, including the halftime show of Superbowl XXVII. |

|||

'HIStory: Past, Present, and Future, Book I' |

|||

Jackson's musical career began to decline with the lukewarm reception to 1995's HIStory: Past, Present, and Future, Book I, which featured some of his earlier hits as well as new material. The record spawned two hits, "You Are Not Alone" and his duet with sister Janet Jackson, "Scream." The spaceship-themed video for "Scream," which cost a record-setting $7 million to produce, earned a Grammy Award for its slick effects. However, another track from the album, "They Don't Care About Us," brought Jackson intense criticism for using an anti-Semitic term. |

|||

'Invincible' (2001) |

|||

Jackson returned to the studio to put together Invincible (2001), his first full album of new material in a decade. |

|||

'Michael' (2010) |

|||

In December 2010, the posthumous album Michael was released amid controversy about whether the singer actually performed some of the tracks. Brother Randy was among those who questioned the authenticity of the recordings, but the Jackson estate later refuted the claims, according to The New York Times. |

|||

'Xscape' (2014) |

|||

Another posthumous album, Xscape, was released in May 2014. R&B star and Jackson protege Usher performed its first single, "Love Never Felt So Good," that month at the iHeartRadio Music Awards. The album, which includes eight songs recorded by Jackson between 1983 and 1999, debuted at No. 2 on Billboard's Top 200 Album chart. |

|||

Michael Jackson's Wives |

|||

In August 1994, Jackson announced that he had married Lisa Marie Presley, daughter of rock icon Elvis Presley. The couple gave a joint television interview with Diane Sawyer, but the union proved to be short-lived. They divorced in 1996. Some thought that the marriage was a publicity ploy to restore Jackson's image after the molestation allegations. Later that same year, Jackson wed nurse Debbie Rowe. The couple divorced in 1999. |

|||

Michael Jackson’s Children |

|||

Michael Jackson and wife Debbie Rowe had two children through artificial insemination: Son Michael Joseph "Prince" Jackson Jr., born in 1997, and daughter Paris Michael Katherine Jackson, born in 1998. When Rowe and Jackson divorced, Michael received full custody of their two children. Jackson would go on to have a third child, Prince Michael "Blanket" Jackson II, with an unknown surrogate. |

|||

After Jackson's death in June 2009, his children were placed in the care of their grandmother, Katherine Jackson, as dictated in his will. In respect to their father's wishes, Prince, Paris and Blanket were largely kept out of the limelight. They stepped up to the mic in 2009 to speak to fans at their father's funeral, and again in January 2010 to accept a posthumous Lifetime Achievement Award for their father at the Grammys. |

|||

In July 2012, a judge temporarily suspended Katherine Jackson's guardianship of Prince, Paris and Blanket after she was erroneously reported missing by a relative. During this time, T.J. Jackson, son of Tito, received temporary custody of the children. Katherine's "disappearance" came shortly after a dispute between her and several members of the Jackson clan, who raised questions about the validity of Michael Jackson's will, pointed fingers at the Jackson matriarch and called for the executors of his estate to resign. |

|||

It was soon discovered that the elderly woman wasn't missing, but had simply taken a trip to Arizona. On August 2, 2012, a judge restored Katherine Jackson as the primary guardian of Prince, Paris and Blanket, also approving a plan granting T.J. Jackson co-guardianship of the children. |

|||

When Did Michael Jackson Die? |

|||

Michael Jackson died on June 25, 2009 at the age of 50. Jackson suffered cardiac arrest in his Los Angeles home and was rushed to the hospital after his heart stopped and CPR attempts failed. He died later that morning. |

|||

How Did Michael Jackson Die? |

|||

In February 2010, an official coroner's report revealed Michael Jackson's cause of death was acute propofol intoxication, or a lethal overdose on a prescription drug cocktail including the sedatives midazolam, diazepam and lidocaine. Aided by his personal physician, Dr. Conrad Murray, Jackson took the drugs to help him sleep at night. Murray told police that he believed Jackson had developed a particular addiction to propofol, which Jackson referred to as his "milk." Murray reportedly administered propofol by IV in the evenings, in 50-milligram dosages, and was attempting to wean the pop star off the drug around the time of his death. |

|||

A police investigation revealed that Murray was not licensed to prescribe most controlled drugs in the state of California. The steps he had taken to save Jackson also came under scrutiny, as evidence showed that the standard of care for administering propofol had not been met, and the recommended equipment for patient monitoring, precision dosing and resuscitation had not been present. As a result, Jackson's death was ruled a homicide, and Murray was convicted of involuntary manslaughter on November 7, 2011, earning a maximum prison sentence of four years. |

|||

When and Where Was Michael Jackson Born? |

|||

Michael Jackson was born on August 29, 1958, in Gary, Indiana. |

|||

Parents |

|||

Michael Jackson was one of nine children. His mother, Katherine Jackson, was a homemaker and a devout Jehovah's Witness. His father, Joseph Jackson, had been a guitarist who put aside his musical aspirations to provide for his family as a crane operator. Behind the scenes, Joseph pushed his sons to succeed. He was also reportedly known to become violent with them. |

|||

The Jackson 5 |

|||

Joseph Jackson believed his sons had talent and molded them into a musical group in the early 1960s that would later become known as the Jackson 5. At first, the Jackson Family performers consisted of Michael's older brothers, Tito, Jermaine and Jackie. Michael joined his siblings when he was five years old, and emerged as the group's lead vocalist. He showed remarkable range and depth for such a young performer, impressing audiences with his ability to convey complex emotions. Older brother Marlon also became a member of the group, which evolved into the Jackson 5. |

|||

Michael and his brothers spent endless hours rehearsing and polishing up their act. At first, the Jackson 5 played local gigs and built a strong following. They recorded one single on their own, "Big Boy," with the B-side "You've Changed," but the record failed to generate much interest. |

|||

The Jackson 5 moved on to working as the opening act for such R&B artists as Gladys Knight and the Pips, James Brown, and Sam and Dave. Many of these performers were signed to the legendary Motown record label, and the Jackson 5 eventually caught the attention of Motown founder Berry Gordy. Impressed by the group, Gordy signed them to his label in early 1969. |

|||

Michael and his brothers moved to Los Angeles, where they lived with Gordy and with Diana Ross of the Supremes as they got settled. The Jackson 5 was introduced to the music industry at a special event in August 1969, and the group later opened for the Supremes. Their first album, Diana Ross Presents the Jackson 5, hit the charts in December 1969, with its single, "I Want You Back," reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart shortly afterward. More chart-topping singles quickly followed, such as "ABC," "The Love You Save" and "I'll Be There." |

|||

For several years, Michael Jackson and the Jackson 5 maintained a busy tour and recording schedule, under the supervision of Berry Gordy and his Motown staff. The group became so popular that they even had their own self-titled cartoon show, which ran from 1971 to 1972. |

|||

Despite the group's great success, there was trouble brewing behind the scenes. Tensions mounted between Gordy and Joseph Jackson over the management of his children's careers, with the Jacksons wanting more creative control over their material. The group officially severed ties with Motown in 1976, though Jermaine Jackson remained with the label to pursue his solo career. |

|||

Now calling themselves the Jacksons, the group signed a new recording deal with Epic Records. By the release of their third album for the label, 1978's Destiny, the brothers had emerged as talented songwriters. |

|||

The overwhelmingly positive response to Michael Jackson’s 1979 solo album Off the Wall helped the Jacksons as a group. Triumph (1980) sold more than 1 million copies, and the brothers went on an extensive tour to support the recording. At the same time, Michael continued exploring more ways to branch out on his own. |

|||

In 1983, Jackson embarked on his final tour with his brothers to support the album Victory. The one major hit from the recording was Jackson's duet with Mick Jagger, "State of Shock." |

|||

The Moonwalk |

|||

On a 1983 television special honoring Motown, Jackson performed his No. 1 hit "Billie Jean" and debuted his soon-to-be-famous dance move, the Moonwalk. Jackson, a veteran performer by this time, created this step himself and choreographed the dance sequences for the video of the album's other No. 1 hit, "Beat It." |

|||

Michael Jackson's Plastic Surgery |

|||

Michael Jackson was badly injured while filming a commercial for PepsiCo in 1984, suffering burns to his face and scalp. At the top of his game creatively and commercially, Michael Jackson had signed a $5 million endorsement deal with the soda giant the previous year. Jackson had surgery to repair his injuries and is believed to have begun experimenting with plastic surgery around this time. His face, especially his nose, would become dramatically altered in the coming years. |

|||

Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch |

|||

A shy and quiet person off-stage, Jackson never was truly comfortable with the media attention he received and rarely gave interviews. By the late 1980s, he had created his own fantasy retreat — a California ranch called Neverland. There the singer kept exotic pets, such as a chimpanzee named Bubbles. He also installed amusement park-type rides, and sometimes opened up the ranch for children's events. Around the same time, rumors began swirling that Jackson was lightening the color of his skin to appear more white and sleeping in a special chamber to increase his lifespan. |

|||

Child Molestation Allegations and Career Decline |

|||

In 1993, allegations of child molestation against Jackson emerged. A 13-year-old boy claimed that the music star had fondled him. Jackson was known to have sleepovers with boys at his Neverland Ranch, but this was the first public charge of wrongdoing. The police searched the ranch, but they found no evidence to support the claim. The following year, Jackson settled the case out of court with the boy's family. Other allegations emerged, but Jackson maintained his innocence. That year, Jackson agreed to a rare television interview with Oprah Winfrey. Seeking to quell some of the rumors about his behavior, he explained that the change in his skin tone was the result of a disease known as vitiligo, and opened up about the abuse he suffered from his father. |

|||

By the turn of the century, Jackson was increasingly becoming known for his eccentricities, which included wearing a surgical mask in public. In 2002, Jackson made headlines when he seemed confused and disoriented on stage at the MTV Video Music Awards. Soon after, he received enormous criticism for dangling his baby son, Blanket, over a balcony while greeting fans in Berlin, Germany. In a later interview, Jackson explained that "We were waiting for thousands of fans down below, and they were chanting they wanted to see my child, so I was kind enough to let them see. I was doing something out of innocence." |

|||

In the 2003 television documentary, Living with Michael Jackson, British journalist Martin Bashir spent several months with the singer, even getting him to discuss his relationships with children. Jackson admitted that he continued to have children sleep over at his ranch, even after the 1993 allegations, and that sometimes he slept with the children in his bed. "Why can't you share your bed? That's the most loving thing to do, to share your bed with someone," Jackson told Bashir. |

|||

In 2003, Jackson encountered more legal woes when he was arrested on charges related to incidents with a 13-year-old boy. Facing 10 counts in all, he was charged with lewd conduct with a minor, attempted lewd conduct, administering alcohol to facilitate molestation, and conspiracy to commit child abduction, false imprisonment and extortion. The resulting 2005 trial was a media circus, with fans, detractors and camera crews surrounding the courthouse. More than 130 people testified, including Macaulay Culkin. The actor told the court that he had been friends with Jackson as a young teen, and never had any problems while staying over at the Neverland Ranch. |

|||

Jackson's accuser also appeared via videotape and described how he had been given wine and molested. However, the jury found problems with his testimony, as well as that of his mother, and Jackson was found not guilty of all charges on June 14, 2005. |

|||

Final Years |

|||

In the aftermath of his trial, Jackson's reputation was effectively destroyed and his finances were in shambles. He soon found refuge in his friendship with Bahrain's Prince Salman Bin Hamad Bin Isa Al-Khalifa, who helped the pop star pay his legal and utility bills, and invited him to his country as a personal guest. |

|||

In Bahrain, the prince took care of the singer's expenses and built a recording studio for him. In return, Jackson allegedly promised to collaborate on a new album for Al-Khalifa's record label, write an autobiography and create a stage play. The completed work never materialized, however, and Jackson soon faced a $7 million lawsuit from his friend for reneging on his promises. |

|||

In even greater financial straits, Jackson defaulted on the $24.5 million loan owed on his Neverland Ranch in 2008. Unable to part with cherished keepsakes, including the crystal gloves he used in performances, Jackson sued to block the auction of some of his personal items from the home the following year. |

|||

Around this same time, the largely reclusive Jackson announced that he would be performing a series of concerts as his "final curtain call." Despite all of the allegations and stories of odd behavior, Jackson remained a figure of great interest, as demonstrated by the strong response to his concert plans. Set to appear at the O2 Arena in London, England, beginning July 8, 2009, Jackson saw all of the tickets to his "This Is It" tour sell out in only four hours. Sadly, Michael Jackson would never get to experience the anticipated success of his comeback tour, as he died in June of that same year. |

|||

Michael Jackson’s Funeral and Memorial |

|||

On July 7, 2009, a televised memorial was held for fans of the "King of Pop" at the Staples Center in downtown Los Angeles. While 17,500 free tickets were issued to fans via lottery, an estimated 1 billion viewers watched the memorial on TV or online. Michael Jackson's death resulted in an outpouring of public grief and sympathy. Memorials were erected around the world, including one at the arena where he was set to perform and another at his childhood home in Gary, Indiana. |

|||

The Jackson family held a private funeral on September 3, 2009, at the Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California, for immediate family members and 200 guests. Celebrity mourners included Jackson's ex-wife, Lisa Marie Presley, and actress Elizabeth Taylor. |

|||

'This Is It' |

|||

A documentary of Jackson's preparations for his final tour, entitled This Is It, was released in October 2009. The film, which features a compilation of interviews, rehearsals and backstage footage of its star, made $23 million in its opening weekend and skyrocketed to No. 1 at the box office. This Is It would go on to make $261 million worldwide, becoming the highest grossing concert film of all time. |

|||

Wrongful Death Lawsuit |

|||

In 2013, the Jackson family launched a wrongful death lawsuit against AEG Live, the entertainment company that promoted Michael Jackson's planned comeback series in 2009. They believed that the company had failed to effectively protect the singer while he was under Conrad Murray's care. One of their lawyers, Brian Panish, discussed AEG's alleged wrongdoing in the trial's opening statements on April 29, 2013: "They wanted to be No. 1 at all costs," he said. "We're not looking for any sympathy ... we're looking for truth and justice." |

|||

Jackson family lawyers sought up to $1.5 billion — an estimation of what Michael Jackson could have earned to that point — but in October 2013, a jury determined that AEG wasn't responsible for the singer's death. "Although Michael Jackson's death was a terrible tragedy, it was not a tragedy of AEG Live's making," said company lawyer Marvin S. Putnam. |

|||

Post-Death Legacy |

|||

Since his death, Michael Jackson has been profiled in multiple biographies and inspired the creation of two Cirque du Soleil shows. His debts have also been settled thanks to his earlier investment in the Sony/ATV Music catalog, which includes the publishing rights for songs of such industry heavyweights as the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Taylor Swift. |

|||

Additionally, the King of Pop proved to have earning power that lasted well past his final days. In October 2017, Forbes announced that Jackson had topped the publication's list of top-earning dead celebrities for the fifth straight year, racking in a whopping $75 million. |

|||

Videos |

|||

The Jackson 5 - On Tour |

|||

(TV-14; 1:39) |

|||

The Jackson 5 - Michael's Talent |

|||

(TV-14; 1:21) |

|||

The Jackson 5 - Discovery |

|||

(TV-14; 1:31) |

|||

Michael Jackson - Mini Biography |

|||

(TV-14; 4:19) |

|||

Related Videos |

|||

Marvin Gaye - Mini Biography |

|||

(TV-14; 2:45) |

|||

Janet Jackson - Mini Biography |

|||

(TV-14; 5:20) |

|||

The Supremes - Mini Bio |

|||

(TV-14; 5:29) |

|||

Fact Check |

|||

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us! |

|||

Citation Information |

|||

Article Title |

|||

Michael Jackson Biography |

|||

Author |

|||

Website Name |

|||

The Biography.com website |

|||

URL |

|||

https://www.biography.com/people/michael-jackson-38211 |

|||

Access Date |

|||

January 30, 2018 |

|||

Publisher |

|||

A&E Television Networks |

|||

Last Updated |

|||

January 18, 2018 |

|||

Original Published Date |

|||

n/a |

|||

54.8K |

|||

SHARES |

|||

Ads by Revcontent |

|||

Around The Web |

|||

Born Before 1985? Maryland Will Pay off Your Mortgage - Only if You Claim It! |

|||

Money News Tips |

|||

Have You Seen These New 2017 Crossover SUV's? |

|||

Crossover SUV Sponsored Ads |

|||

Speak A New Language In 3 Weeks With This App Made by 100+ Experts |

|||

The Babbel Magazine |

|||

15 Rock & Roll Goddesses You Probably Forgot About |

|||

Idolator |

|||

New Device Instantly Tells You if There is a Problem with Your Car |

|||

DailyTech |

|||

You Already Pay for Amazon Prime - Here's How You Can Make It Even Better |

|||

Honey |

|||

Bitcoin Expert Reveals 3-Step Secret To Retirement Fortune |

|||

The Altucher Report |

|||

Donnie Wahlberg Leaves $2,000 Tip At Waffle House |

|||

loanpride |

|||

BIO NEWSLETTER |

|||

Sign up to receive updates from BIO and A+E Networks. |

|||

MORE STORIES FROM BIO |

|||

Biography |

|||

Janet Jackson |

|||

Singer, Dancer, Actress, Producer(1966–) |

|||

Biography |

|||

Jackie Jackson |

|||

Guitarist, Singer(1951–) |

|||

Biography |

|||

Jermaine Jackson |

|||

Singer(1954–) |

|||

See More |

|||

About |

|||

Contact Us |

|||

Advertise |

|||

Privacy |

|||

Terms of Use |

|||

Copyright Policy |

|||

Ad Choices |

|||

© 2018 Bio and the Bio logo are registered trademarks of A&E Television Networks, LLC. |

|||

Revision as of 16:41, 30 January 2018

Madam C. J. Walker | |

|---|---|

Walker in 1903 | |

| Born | Sarah Breedlove December 23, 1867 Delta, Louisiana, United States |

| Died | May 25, 1919 (aged 51) Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, United States |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Businesswoman, hair-care entrepreneur, Philanthropist, and Activist |

| Spouse(s) | Moses McWilliams (married 1882–1887) John Davis (married 1894 – c. 1903) Charles Joseph Walker (married 1906–1912) |

| Children | A'Lelia Walker |

| Website | www |

Sarah Breedlove (December 23, 1867 – May 25, 1919), known as Madam C. J. Walker, was an African American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and a political and social activist. Eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America,[1] she became one of the wealthiest African American women in the country, "the world's most successful female entrepreneur of her time," and one of the most successful African-American business owners ever.[2]

Walker made her fortune by developing and marketing a line of beauty and hair products for black women through Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company, the successful business she founded. Walker was also known for her philanthropy and activism. She made financial donations to numerous organizations and became a patron of the arts. Villa Lewaro, Walker’s lavish estate in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York, served as a social gathering place for the African American community.

Early life

Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, near Delta, Louisiana, to Owen and Minerva (Anderson) Breedlove.[3][4] Sarah was one of six children, which included an older sister, Louvenia, and four brothers: Alexander, James, Solomon, and Owen Jr. Breedlove's parents and her older siblings were enslaved on Robert W. Burney's Madison Parish plantation, but Sarah was the first child in her family born into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Her mother died, possibly from cholera, in 1872; her father remarried, but he died within a few years.[citation needed] Orphaned at the age of seven, Sarah moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, at the age of ten and worked as a domestic. Prior to her first marriage, she lived with her older sister, Louvenia, and brother-in-law, Jesse Powell.[3][5]

Marriage and family

In 1882, at the age of fourteen, Sarah married Moses McWilliams, possibly to escape mistreatment from her brother-in-law.[3] Sarah and Moses had one daughter, Lelia McWilliams, born on June 6, 1885. When Moses died in 1887, Sarah was twenty; Lelia was two years old.[5][6] Sarah remarried in 1894, but left her second husband, John Davis, around 1903 and moved to Denver, Colorado, in 1905.[7][8]

In January 1906, Sarah married Charles Joseph Walker, a newspaper advertising salesman she had known in Missouri. Through this marriage, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker. The couple divorced in 1912; Charles died in 1926. Lelia McWilliams adopted her stepfather's surname and became known as A'Lelia Walker.[5][9][10]

Career

In 1888 Sarah and her daughter moved to Saint Louis, Missouri, where three of her brothers lived. Sarah found work as a laundress, barely earning more than a dollar a day, but she was determined to make enough money to provide her daughter with a formal education.[11][12] During the 1880s, Breedlove lived in a community where ragtime music was developed—she sang at the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church and started to yearn for an educated life as she watched the community of women at her church.[1] As was common among black women of her era, Sarah experienced severe dandruff and other scalp ailments, including baldness, due to skin disorders and the application of harsh products such as lye that were included in soaps to cleanse hair and wash clothes. Other contributing factors to her hair loss included poor diet, illnesses, and infrequent bathing and hair washing during a time when most Americans lacked indoor plumbing, central heating and electricity.[10][13][14]

Initially, Sarah learned about hair care from her brothers, who were barbers in Saint Louis.[13] Around the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (World's Fair at St. Louis in 1904), she became a commission agent selling products for Annie Turnbo Malone, an African American hair-care entrepreneur and owner of the Poro Company.[3] While working for Malone, who would later become Walker’s largest rival in the hair-care industry,[1] Sarah began to adapt her knowledge of hair and hair products to develop her own product line.[9]

In July 1905, when she was thirty-seven years old, Sarah and her daughter moved to Denver, Colorado, where she continued to sell products for Malone and develop her own hair-care business. Following her marriage to Charles Walker in 1906, she became known as Madam C. J. Walker and marketed herself as an independent hairdresser and retailer of cosmetic creams. (“Madam” was adopted from women pioneers of the French beauty industry.[16]) Her husband, who was also her business partner, provided advice on advertising and promotion; Sarah sold her products door to door, teaching other black women how to groom and style their hair.[5][9]

In 1906 Walker put her daughter in charge of the mail order operation in Denver while she and her husband traveled throughout the southern and eastern United States to expand the business.[11][13][14][17] In 1908 Walker and her husband relocated to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where they opened a beauty parlor and established Lelia College to train "hair culturists." After closing the business in Denver in 1907, A'lelia ran the day-to-day operations from Pittsburgh, while Walker established a new base in Indianapolis in 1910.[18] A'lelia also persuaded her mother to establish an office and beauty salon in New York City's Harlem neighborhood in 1913.[16]

In 1910 Walker relocated her business to Indianapolis, where she established the headquarters for the Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company. She initially purchased a house and factory at 640 North West Street.[19] Walker later built a factory, hair salon, and beauty school to train her sales agents, and added a laboratory to help with research.[14] She also assembled a competent staff that included Freeman Ransom, Robert Lee Brokenburr, Alice Kelly, and Marjorie Stewart Joyner, among others, to assist in managing the growing company.[9] Many of her company's employees, including those in key management and staff positions, were women.[16]

To increase her company's sales force, Walker trained other women to become "beauty culturists" using "The Walker System", her method of grooming that was designed to promote hair growth and to condition the scalp through the use of her products.[9] Walker's system included a shampoo, a pomade stated to help hair grow, strenuous brushing, and applying iron combs to hair. This method claimed to make lackluster and brittle hair become soft and luxurious.[11][13] Walker's product line had several competitors. Similar products were produced in Europe and manufactured by other companies in the United States, which included her major rivals, Annie Turnbo Malone's Poro System and later, Sarah Spencer Washington's Apex System.[20]

Between 1911 and 1919, during the height of her career, Walker and her company employed several thousand women as sales agents for its products.[5] By 1917 the company claimed to have trained nearly 20,000 women.[19] Dressed in a characteristic uniform of white shirts and black skirts and carrying black satchels, they visited houses around the United States and in the Caribbean offering Walker's hair pomade and other products packaged in tin containers carrying her image. Walker understood the power of advertising and brand awareness. Heavy advertising, primarily in African American newspapers and magazines, in addition to Walker's frequent travels to promote her products, helped make Walker and her products well known in the United States. Walker's name became even more widely known by the 1920s, after her death, as her company's business market expanded beyond the United States to Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Panama, and Costa Rica.[11][13][16][20]

In addition to training in sales and grooming, Walker showed other black women how to budget, build their own businesses, and encouraged them to become financially independent. In 1917, inspired by the model of the National Association of Colored Women, Walker began organizing her sales agents into state and local clubs. The result was the establishment of the National Beauty Culturists and Benevolent Association of Madam C. J. Walker Agents (predecessor to the Madam C. J. Walker Beauty Culturists Union of America).[5] Its first annual conference convened in Philadelphia during the summer of 1917 with 200 attendees. The conference is believed to have been among the first national gatherings of women entrepreneurs to discuss business and commerce.[10][11] During the convention Walker gave prizes to women who had sold the most products and brought in the most new sales agents. She also rewarded those who made the largest contributions to charities in their communities.[11]

Activism and philanthropy

As Walker's wealth and notoriety increased, she became more vocal about her views. In 1912 Walker addressed an annual gathering of the National Negro Business League (NNBL) from the convention floor, where she declared: "I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there, I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there, I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations. I have built my own factory on my own ground.[19]" The following year she addressed convention-goers from the podium as a keynote speaker.[11][13]

Walker helped raise funds to establish a branch of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) in Indianapolis's black community, pledging $1,000 to the building fund for the Senate Avenue YMCA. Walker also contributed scholarship funds to the Tuskegee Institute. Other beneficiaries included Indianapolis's Flanner House and Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church; Mary McLeod Bethune's Daytona Education and Industrial School for Negro Girls (which later became Bethune-Cookman University) in Daytona Beach, Florida; the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina; and the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Georgia. Walker was also a patron of the arts.[5][11]

About 1913 Walker's daughter, A'Lelia, moved to a new townhouse in Harlem, and in 1916 Walker joined her in New York, leaving the day-to-day operation of her company to her management team in Indianapolis.[4][19] In 1917 Walker commissioned Vertner Tandy, the first licensed black architect in New York City and a founding member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, to design her house in Irvington-on-Hudson, New York. Walker intended for Villa Lewaro, which cost $250,000 to build, to become a gathering place for community leaders and to inspire other African Americans to pursue their dreams.[20][21][22] She moved into the house in May 1918 and hosted an opening event to honor Emmett Jay Scott, at that time the Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs of the U.S. Department of War.[13]

Walker became more involved in political matters after her move to New York. She delivered lectures on political, economic, and social issues at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions. Her friends and associates included Booker T. Washington, Mary McLeod Bethune, and W. E. B. Du Bois.[5] During World War I Walker was a leader in the Circle For Negro War Relief and advocated for the establishment of a training camp for black army officers.[19] In 1917 she joined the executive committee of New York chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which organized the Silent Protest Parade on New York City's Fifth Avenue. The public demonstration drew more than 8,000 African Americans to protest a riot in East Saint Louis that killed thirty-nine African Americans.[11]

Profits from her business significantly impacted Walker's contributions to her political and philanthropic interests. In 1918 the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC) honored Walker for making the largest individual contribution to help preserve Frederick Douglass’s Anacostia house.[23] Prior to her death in 1919, Walker pledged $5,000 (the equivalent of about $65,000 in 2012) to the NAACP's anti-lynching fund. At the time it was the largest gift from an individual that the NAACP had ever received. Walker bequeathed nearly $100,000 to orphanages, institutions, and individuals; her will directed two-thirds of future net profits of her estate to charity.[1][11][16]

Death and legacy

Walker died on May 25, 1919, from kidney failure and complications of hypertension at the age of fifty-one.[5][19][22] Walker's remains are interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.[24]

At the time of her death Walker was considered to be the wealthiest African American woman in America. She was eulogized as the first female self-made millionaire in America, but Walker's estate was only worth an estimated $600,000 (approximately $8 million in present-day dollars) upon her death.[1] According to Walker's New York Times obituary, "she said herself two years ago [in 1917] that she was not yet a millionaire, but hoped to be some time."[22] At the time of Walker's death, the average American's annual salary was $750.[25] Her daughter, A'Lelia Walker, became the president of the Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company.[13]

Walker's personal papers are preserved at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis.[10] Her legacy also continues through two properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places: Villa Lewaro in Irvington, New York, and the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Villa Lewaro was sold following A'Lelia Walker's death to a fraternal organization called the Companions of the Forest in America in 1932. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has designated the privately owned property a National Treasure.[26][27] Indianapolis's Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters building, renamed the Madame Walker Theatre Center, opened in December 1927; it included the company's offices and factory as well as a theater, beauty school, hair salon and barbershop, restaurant, drugstore, and a ballroom for the community. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[16][28]

In 2006, playwright and director Regina Taylor wrote The Dreams of Sarah Breedlove, recounting the history of Walker’s struggles and success.[29] The play premiered at the Goodman Theater in Chicago.[30] Actress L. Scott Caldwell played the role of Walker.[29]

On March 4, 2016, skincare and haircare company Sundial Brands launched a collaboration with Sephora in honor of Walker’s legacy. The launch, titled “Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture”, comprised four collections and focused on the use of natural ingredients to care for different types of hair.[31] As of 2017, actress Octavia Spencer has committed to portray Walker in a TV series based on the biography of Walker by A’Lelia Bundles, Walker's great-great-granddaughter.[32]

Tributes

Various scholarships and awards have been named in Walker's honour:

- The Madam C. J Walker Business and Community Recognition Awards are sponsored by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Oakland/Bay Area chapter. An annual luncheon honours Walker and awards outstanding women in the community with scholarships.[33]

- Spirit Awards have sponsored the Madame Walker Theatre Center in Indianapolis. Established as a tribute to Walker, the annual awards have honoured national leaders in entrepreneurship, philanthropy, civic engagement, and the arts since 2006. Awards presented to individuals include the Madame C. J Walker Heritage Award as well as young entrepreneur and legacy prizes.[34]

Walker was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca, New York, in 1993.[35] In 1998 the U.S. Postal Service issued a Madam Walker commemorative stamp as part of its Black Heritage Series.[19][36]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Madam C. J. Walker". The Philanthropy Hall of Fame. Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ Glaeser, Edward (2011), Triumph of the City: How Our Best Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier, New York: Penguin Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-1-59420-277-3

- ^ a b c d Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, p. 1209.

- ^ a b Bundles, A’Lelia. "Madam C.J. Walker". Madame C.J. Walker. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Madam C. J. Walker". Indiana Historical Society. Retrieved 2015-02-28.

- ^ A'lelia Bundles (2014). "Biography of Madam C. J. Walker". National Coalition of 100 Black Women, Inc., Oakland/Bay Area Chapter. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

- ^ Linda C. Gugin and James E. St. Clair, eds. (2015). Indiana's 200: The People Who Shaped the Hoosier State. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-87195-387-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "The Philanthropy Hall of Fame: Madam C. J. Walker". Philanthropy Roundtable. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e Bundles, "Madam C J (Sarah Breedlove) Walker, 1867–1919" in Black Women in America, v. II, pp. 1210–11.

- ^ a b c d Andrea Riquier (2015-02-24). "Madam Walker Went from Laundress to Success". Investor's Business Daily. Retrieved 2016-02-08.