Sound reinforcement system: Difference between revisions

uploaded a new image of live mixing consoles |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

In recent years, wireless technology has become increasingly popular in sound reinforcement, typically used for electric guitar, bass, and handheld microphones. This has granted performers the freedom to move about the stage during the show without the worry of tripping over or disconnecting the cable. |

In recent years, wireless technology has become increasingly popular in sound reinforcement, typically used for electric guitar, bass, and handheld microphones. This has granted performers the freedom to move about the stage during the show without the worry of tripping over or disconnecting the cable. |

||

[[ |

[[File:Two Consoles at FOH.jpg|thumb|left|300 px|A Yamaha PM4000 and a Heritage 3000 mixing console at the Front of House position at an outdoor concert.]] |

||

===Mixing consoles=== |

===Mixing consoles=== |

||

[[Mixing console]]s are the heart of a sound reinforcement system. This is where the operator can mix, equalize and add effects to sound sources. Multiple consoles can be used for different applications in a single sound reinforcement system. The Front of House (FOH) mixing console must be located where the operator can see the action on stage and hear the output of the loudspeaker system. Some venues with permanently installed systems such as religious facilities and theaters place the mixing console within an enclosed booth but this approach is more common for broadcast and recording applications. Sound reinforcement mixing from an enclosed booth prevents the operator from hearing the combined effect of the artist, loudspeakers, audience, and the acoustics of the room. {{Fact|date=September 2007}} |

[[Mixing console]]s are the heart of a sound reinforcement system. This is where the operator can mix, equalize and add effects to sound sources. Multiple consoles can be used for different applications in a single sound reinforcement system. The Front of House (FOH) mixing console must be located where the operator can see the action on stage and hear the output of the loudspeaker system. Some venues with permanently installed systems such as religious facilities and theaters place the mixing console within an enclosed booth but this approach is more common for broadcast and recording applications. Sound reinforcement mixing from an enclosed booth prevents the operator from hearing the combined effect of the artist, loudspeakers, audience, and the acoustics of the room. {{Fact|date=September 2007}} |

||

Revision as of 01:04, 25 January 2009

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2009) |

A sound reinforcement system is an arrangement of microphones, electronic signal processors, amplifiers, and loudspeakers that makes live or pre-recorded sounds—usually music or speech— louder, or that distributes the sound to a larger or more distant audience. [1][2] A sound reinforcement system may be very complex, including hundreds of microphones, complex mixing and signal processing systems, tens of thousands of watts of amplification, and multiple loudspeaker arrays, all overseen by a team of audio engineers and technicians. On the other hand, a sound reinforcement system can be as simple as a small PA system in a coffeehouse, consisting of a single microphone connected to a self-powered 100-watt loudspeaker system. In both cases, these systems reinforce sound to make it louder or distribute it to a wider audience.[3]

Audio engineers and other sound industry professionals disagree over whether these audio systems should be called sound reinforcement (SR) systems or public address (PA) systems. Some audio engineers distinguish between the two terms by technology and capability, while others distinguish by intended use (e.g., SR systems are for live music whereas PA systems are usually for reproduction of speech and recorded music in buildings and institutions). In some regions or markets, the distinction between the two terms is important. On the other hand, the terms are considered interchangeable in some areas.[4]

Basic concept

A typical sound reinforcement system consists of three parts: input transducers such as microphones, which convert sound energy into an audio signal; signal processors such as equalizers and amplifiers, which alter the audio signal characteristics; and output transducers such as loudspeakers, which convert the audio signal into sound for an audience.

Sound is taken and converted into electronic signal by an input transducer (such as a microphone or a pickup on an electric guitar or electric bass). A signal processor (such as a mixing console, amplifier, a reverb effect, or other devices) then alters the signal's equalization, balance, effects and amplitude. Finally, an output transducer such as a loudspeaker (or, for audio engineers, a set of headphones) converts the electronic signal back into sound, so that the listener can hear the end product. This basic concept of sound reinforcement systems encompasses anything from a simple system with only one microphone, amplifier and loudspeaker, to the complex systems in professional applications including multiple mixing boards, monitors and a vast selection of effects.

Signal path

Sound reinforcement in a large format system typically uses a signal path which starts with the directly-connected instrument or a microphone (transducer) which is plugged into the multicore cable (often called a "snake"). The snake routes the signals of all of the inputs to the Front of the House (FOH) mixer and to the monitor consoles. Once the signal is in a channel on the console, this signal can be equalized, panned and routed to various mix buses. The signal may also be patched or routed into an external effect processor (e.g. gate, compressor, reverb).

The signal can be routed internally to a summation bus (also known as a "bus", mix group, subgroup or simply 'group'), to allow the engineer to control the levels of several related signals at once. For example, all of the different microphones for a drum set might be grouped together so that the volume of the entire drum set sound can be controlled with a single fader.[5] From here each signal is routed through the stereo masters on a console (left and right, or balance, pan, etc.). Each signal can be sent to additional outputs referred to as auxiliary sends, or "auxes."

The next step in the signal path generally depends on the size of the system in place. In smaller systems, the main outputs would be sent to an additional equalizer, or directly to a power amplifier, with one or more loudspeakers (typically two) then connected to that amplifier. In large-format systems, the signal is first routed through an additional equalizer then to a crossover. A crossover splits the signal into multiple frequency bands with each band being sent to separate amplifiers and speaker enclosures for low-, middle-, and high-frequency sounds. Low-frequency sounds are usually sent to subwoofers, and middle- and high-frequency sounds are usually sent to full-range speaker cabinets.

System components

Input transducers

Many types of input transducers can be found in a sound reinforcement system, with microphones being the most commonly used input device. They can be classified according to their method of transduction, pickup (or polar) pattern or their functional application. Most microphones used in sound reinforcement are either dynamic or condenser microphones.

Microphones used for sound reinforcement are positioned and mounted in many ways, including base-weighted upright stands, podium mounts, tie-clips, instrument mounts, and headset mounts. Headset mounted and tie-clip mounted microphones are often used with wireless transmission to allow performers or speakers to move freely. Early adopters of headset mounted microphones technology included country singer Garth Brooks[6], Kate Bush, and Madonna. [7]

There are many other types of input transducers which may be used occasionally, including magnetic pickups used in electric guitars and electric basses, contact microphones used on stringed instruments, and piano and phonograph pickups (cartridges) used in record players [8].

In recent years, wireless technology has become increasingly popular in sound reinforcement, typically used for electric guitar, bass, and handheld microphones. This has granted performers the freedom to move about the stage during the show without the worry of tripping over or disconnecting the cable.

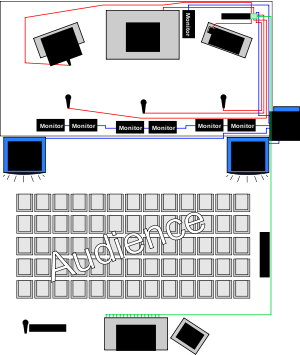

Mixing consoles

Mixing consoles are the heart of a sound reinforcement system. This is where the operator can mix, equalize and add effects to sound sources. Multiple consoles can be used for different applications in a single sound reinforcement system. The Front of House (FOH) mixing console must be located where the operator can see the action on stage and hear the output of the loudspeaker system. Some venues with permanently installed systems such as religious facilities and theaters place the mixing console within an enclosed booth but this approach is more common for broadcast and recording applications. Sound reinforcement mixing from an enclosed booth prevents the operator from hearing the combined effect of the artist, loudspeakers, audience, and the acoustics of the room. [citation needed]

Large music productions often use a separate stage monitor mixing console which is dedicated to creating mixes for the performers' on-stage or in-ear monitors. These consoles are typically placed at the side of the stage so that the operator can communicate with the performers on stage. [9] In cases where performers have to play at a venue that does not have a monitor engineer near the stage, the monitor mixing is done by the FOH engineer from the FOH console, which is located amongst the audience or at the back of the hall. This arrangement can be problematic because the performers end up having to request changes to the monitor mixes with "...hand signals and clever cryptic phrases". The engineer also cannot hear the changes that he is applying to the monitors on stage, often resulting in a reduction of the quality of the mix.[10]

Signal processors

Equalizers

Equalizers exist in sound reinforcement systems in two forms: graphic and parametric. Both of these are used in conjunction with high-pass and low-pass filters. Parametric equalizers are often built into each channel in mixing consoles and are also available as separate units. Parametric equalizers first became popular in the 1970s and have remained the program equalizer of choice for many engineers since then.

Graphic equalizers have faders which resemble a frequency response curve plotted on a graph. Sound reinforcement systems typically use graphic equalizers with one-third octave frequency centers. These are typically used to equalize output signals going to the main loudspeaker system or the monitors on stage.

High-pass (low-cut) and low-pass (high-cut) filters restrict a given channel's bandwidth extremes which can prevent subsonic disturbances and RF or lighting control disturbances from interfering with the audio system. Filter sections are often included with graphic and parametric equalizers to give full control of the frequency range. If their response is steep enough, high-pass filters and low-pass filters function as end-cut filters. A feedback suppressor is a specialized type of band-pass filter which automatically detects and suppresses feedback by greatly attenuating the frequency which is feeding back.

Compressors

Compressors are designed to manage the dynamic range of an audio signal. A compressor accomplishes this by reducing the level of a signal above a defined level (threshold) by a defined amount (ratio). Most compressors available are designed to allow the operator to select a ratio within a range typically between 1:1 and 20:1, with some allowing settings of up to ∞:1. A compressor with an infinite ratio is typically referred to as a limiter. The speed that the compressor adjusts the gain of the signal is typically adjustable as is the final output of the device.

Compressor applications vary widely from objective system design criterion to subjective applications determined by variances in program material and engineer preference. Some system design criteria specify limiters for component protection and gain structure control. Artistic signal manipulation is a subjective technique widely utilized by mix engineers to improve clarity or to creatively alter the signal in relation to the program material. An example of artistic compression is the typical heavy compression used on the various components of a modern rock drum kit. The drums are processed to be perceived as sounding more punchy and full.

Noise gates

A noise gate sets a threshold where if it is quieter it will not let the signal pass and if it is louder it opens the gate. A noise gate's function is in a sense the opposite to that of a compressor. Noise gates are useful for microphones which will pick up noise which is not relevant to the program, such as the hum of a miked electric guitar amplifier or the rustling of papers on a minister's podium.

Noise gates are also used to process the microphones placed near the drums of a drum kit in many hard rock and metal bands. Without a noise gate, the microphone for a specific instrument such as the floor tom will also pick up signal from nearby drums or cymbals. With a noise gate, the threshold of sensitivity for each microphone on the drum kit can be set so that only the direct strike and subsequent decay of the drum will be heard, not the nearby sounds.

Effects

Reverberation and delay effects are widely used in sound reinforcement systems to enhance the mix relative to the desired artistic impact of the program material. Modulation effects such as flanging, phasing, and chorusing are also applied to some instruments. An exciter "livens up" the sound of audio signals by applying dynamic equalization, phase manipulation and harmonic synthesis of typically high frequency signals.

The appropriate type, variation, and level of effects is quite subjective and is often collectively determined by a production's engineer, artist, or musical director. Reverb, for example, can give the effect of signal being present in anything from a small room to a massive stadium, or even in a space that doesn't exist in the physical world. The use of reverb often goes unnoticed by the audience, as it often sounds more natural than if the signal was left dry. [11] The use of effects in the reproduction of modern music is often in an attempt to mimic the sound of the studio version of the artist's music.

Power amplifiers

Power amplifiers boost a signal level and provide current to drive a loudspeaker. All output transducers require amplification of the signal by an amplifier, including loudspeakers, monitor speakers, and headphones. Most professional amplifiers provide protection from overdriven signals, short circuits across the output, and thermal overload. Limiters are often used to protect loudspeakers and amplifiers from signal overload.

Like most sound reinforcement equipment products, professional amplifiers are designed to be mounted within 19-inch racks. Many power amplifiers feature internal fans to draw air across their heat sinks. Since they can generate a significant amount of heat, thermal dissipation is an important factor for operators to consider when mounting amplifiers into equipment racks.[12] Active loudspeakers feature internally mounted amplifiers that have been selected by the manufacturer to be the best amplifier for use with the given loudspeaker.

Many powerful amplifiers have been designed as class AB amplifiers which need bulky transformers made of copper wiring and large metal heat sinks for cooling. However, class D amplifiers, which are much more efficient, weigh less than, and produce an equivalent power output of class AB amplifiers are commonly used as well. The use of class A amplifiers is typically limited to studio applications, where the highly detailed clarity of an amplifier is going to be much more noticeable and the power requirements are much less.

Digital loudspeaker management systems (DLMS) that combine digital crossover functions, compression, limiting, and other features in a single unit have become popular since their introduction. They are used to process the mix from the mixing console and route it to the various amplifiers in use. Systems may include several loudspeakers, each with its own output optimized for a specific range of frequencies (i.e. bass, midrange and treble). Bi, tri, or quad amplifying a sound reinforcement system with the aide of a DLMS results in a more efficient use of amplifier power by sending each amplifier only the frequencies appropriate for its respective loudspeaker. Most DLMS units that are designed for use by non-professionals have calibration and testing functions such as a pink noise generator coupled with a real-time analyzer to allow automated room equalization.

Output transducers

Main loudspeakers

A simple and inexpensive PA loudspeaker may have a single full-range loudspeaker driver, housed in a suitable enclosure. More elaborate, professional-caliber sound reinforcement loudspeakers may incorporate separate drivers to produce low, middle, and high frequency sounds. A crossover network routes the different frequencies to the appropriate drivers. In the 1960s, horn loaded theater loudspeakers and PA speakers were almost always "columns" of multiple drivers mounted in a vertical line within a tall enclosure. The 1970s to early 1980s was a period of innovation in loudspeaker design with many sound reinforcement companies designing their own speakers. The basic designs were based on commonly known designs and the speaker components were commercial speakers made by JBL, Altec Lansing, Electro-Voice, Meyer, and others. The areas of innovation were in cabinet design, durability, ease of packing and transport, and ease of setup. This period also saw the introduction of the hanging or "flying" of main loudspeakers at large concerts. During the 1980s the large speaker manufactures started producing standard products using the innovations of the 1970s. These were mostly smaller two way systems with 12", 15" or double 15" woofers and a high frequency driver attached to a high frequency horn. The 1980s also saw the start of loudspeaker companies focused on the sound reinforcement market such as Meyer Sound and Eastern Acoustic Works. The 1990s saw the introduction of Line arrays where long vertical arrays of loudspeakers with a smaller cabinet are used to increase efficiency and provide even dispersion and frequency coverage. This period also saw the introduction of inexpensive molded plastic speaker enclosures mounted on tripod stands. Many feature built-in power amplifiers which made them practical for non-professionals to set up and operate successfully. The sound quality available from these simple 'powered speakers' varies widely depending on the implementation.

Many sound reinforcement loudspeaker systems incorporate protection circuitry, preventing damage from excessive power or operator error. Positive temperature coefficient resistors, specialized current-limiting light bulbs, and circuit-breakers were used alone or in combination to reduce driver failures. During the same period, the professional sound reinforcement industry made the Neutrik Speakon NL4 and NL8 connectors the standard input connectors, replacing 1/4" jacks, XLR connectors, and Cannon multipin connectors which are all limited to a maximum of 15 amps of current. XLR connectors are still the standard input connector on active loudspeaker cabinets.

The three different types of transducers are subwoofers, compression drivers, and tweeters. They all feature the combination of a voicecoil, magnet, cone or diaphragm, and a frame or structure. Loudspeakers have a power rating (in watts) which indicates their maximum power capacity, to help users avoid overpowering them. Thanks to the efforts of the Audio Engineering Society (AES) and the loudspeaker industry group ALMA, power-handling specifications became more trustworthy, although adoption of the EIA-426-B standard is far from universal. Around the mid 1990s trapezoidal-shaped enclosures became popular as this shape allowed many of them to be easily arrayed together.

Professional sound reinforcement speaker systems often include dedicated hardware for "flying" them above the stage area, to provide more even sound coverage and to maximize sight lines within performance venues.

Monitor loudspeakers

Monitor loudspeakers, also called 'foldback' loudspeakers, are situated towards a performer or a section of the stage. They are generally sent a different mix of vocals or instruments than the mix that is sent to the main loudspeaker system. Monitor loudspeaker cabinets are often a wedge shape, directing their output upwards towards the performer when set on the floor of the stage. Two-way, dual driver designs are common as monitor loudspeakers need to be smaller to save space on the stage. These loudspeakers typically require less power and volume than the main loudspeaker system, as they only need to provide sound for a few people who are in relatively close proximity to the loudspeaker. Some manufacturers have designed loudspeakers for use either as a component of a small PA system or as a monitor loudspeaker.

Using monitor speakers instead of in ear monitors typically results in an increase of stage volume, which can lead to more feedback issues and progressive hearing damage for the performers in front of them.[13] The clarity of the mix for the performer on stage is also typically not as clear as they hear more extraneous noise from around them. The use of monitor loudspeakers, active or passive, requires more cabling and gear on stage, resulting in an even more cluttered stage. These factors, amongst others, have led to the increasing popularity of in ear monitors.

In-Ear Monitors

In-ear monitors are headphones that have been designed for use as monitors by a live performer. They are either of a "universal fit" or "custom fit" design. The universal fit in ear monitors feature rubber or foam tips that can be inserted into virtually anybody's ear. Custom fit in ear monitors are created from an impression of the users ear that has been made by an audiologist. In ear monitors are almost always used in conjunction with a wireless transmitting system, allowing the performer to freely move about the stage whilst maintaining their monitor mix.

In ear monitors offer considerable isolation for the performer using them, meaning that the monitor engineer can craft a much more accurate and clear mix for the performer. A downside of this isolation is that the performer cannot hear the crowd or other performers on stage that do not have microphones. This has been remedied by larger productions by setting up a pair of microphones on each side of the stage facing the audience that are mixed into the in ear monitor sends.[13]

Since their introduction in the mid 1980's, in ear monitors have grown to be the most popular monitoring choice for large touring acts. The reduction or elimination of loudspeakers other than instrument amplifiers on stage has allowed for cleaner and less problematic mixing situations for both the front of house and monitor engineers. Feedback is easier to manage and there is less sound reflecting off the back wall of the stage out into the audience, which effects the clarity of the mix the front of house engineer is attempting to create.

Applications

Sound reinforcement systems are used in a broad range of different settings, each of which poses different challenges.

Church sound

Designing systems in churches and similar religious facilities often poses a challenge, because the speakers have to be unobtrusive to blend in with antique woodwork and stonework. In some cases, audio designers have designed custom-painted speaker cabinets so that the speakers will blend in with the church architecture. Some church facilities, such as sanctuaries or chapels are long rooms with low ceilings, which means that additional fill-in speakers are needed throughout the room to give good coverage. An additional challenge with church SR systems is that, once installed, they are often operated by amateur volunteers from the congregation, which means that they must be easy to run and troubleshoot.

Some mixing consoles designed for houses of worship have automatic mixers, which turn down unused channels to reduce noise, and automatic feedback elimination circuits which detect and notch out frequencies that are feeding back. These features may also be available in multi-function consoles used in convention facilities and multi-purpose venues.

Touring systems

Touring sound systems have to be powerful and versatile enough to cover many different rooms, often being of many different sizes and shapes. They also need to use "field-replaceable" components such as speakers, horns, and fuses, which are easily accessible for repairs during a tour. Tour sound systems are often designed with substantial redundancy features, so that in the event of equipment failure or amplifier overheating, the system will continue to function. Touring systems for acts performing for crowds of a few thousand people and up are typically set up and operated by a team of technicians and engineers that travel with the talent to every show.

It is not uncommon for mainstream acts that are going to perform in mid to large venues during their tour to schedule one to two weeks of tech rehearsal with the entire concert system and production staff at hand. This allows the audio and lighting engineers to become familiar with the show and establish presets on their digital equipment for each part of the show, if needed. Many modern musical groups work with their Front of House and Monitor Mixing Engineers during this time to establish what their general idea is of how the show should sound, both for themselves on stage and for the audience. This often involves programming different effects and signal processing for use on specific songs in an attempt to make the songs sound somewhat similar to the studio versions. To manage a show with a lot of these types of changes, the mixing engineers for the show often choose to use a Digital Mixing Console so that they can recall these many settings in between each song. This time is also used by the system technicians to get familiar with the specific combination of gear that is going to be used on the tour and how it acoustically responds during the show. These technicians remain busy during the show, making sure the SR system is operating properly and that the system is tuned correctly, as the acoustic response of a room will respond differently throughout the day depending on the temperature, humidity, and number of people in the room.

Weekend band PA systems are a niche market for touring SR gear. Weekend bands need systems that are small enough to fit into a minivan or a car trunk, and yet powerful enough to give adequate and even sound dispersion and vocal intelligibility in a noisy club or bar. As well, the systems need to be easy and quick to set up. Sound reinforcement companies have responded to this demand by offering equipment that fulfills multiple roles, such as "amp-mixers" (a mixer with an integrated power amplifier and effects) and powered subwoofers (a subwoofer with an integrated power amplifier and crossover). These products minimize the amount of wiring connections that bands have to make to set up the system. Some subwoofers have speaker mounts built into the top, so that they can double as a base for the stand-mounted full-range PA speaker cabinets.

Sports sound systems

Systems for outdoor sports facilities and ice rinks often have to deal with substantial echo, which can make speech unintelligible. Sports and recreational sound systems often face environmental challenges as well, such as the need for weather-proof outdoor speakers in outdoor stadiums and humidity- and splash-resistant speakers in swimming pools.

Live theater

Sound for live theater, operatic theater, and other dramatic applications may pose problems similar to those of churches, in cases where a theater is an old heritage building where speakers and wiring may have to blend in with woodwork. The need for clear sight lines in some theaters may make the use of regular speaker cabinets unacceptable; instead, slim, low-profile speakers are often used instead.

In live theater and drama, performers move around onstage, which means that wireless microphones may have to be used. Wireless microphones need to be set up and maintained properly, to avoid interference and reception problems.

Some of the higher budget theater shows and musicals are mixed in surround sound live, often with the show's Sound Designer triggering sound effects that are being mixed with music and dialogue by the show's mixing engineer. These systems are usually much more extensive to design, typically involving a separate sets of speakers for different zones in the theater.

Classical music and opera

A subtle type of sound reinforcement called acoustic enhancement is used in some concert halls where classical music such as symphonies and opera is performed. Acoustic enhancement systems help give a more even sound in the hall and prevent "dead spots" in the audience seating area by "...augment[ing] a hall's intrinsic acoustic characteristics." The systems use "...an array of microphones connected to a computer [which is] connected to an array of loudspeakers." However, as concertgoers have become aware of the use of these systems, debates have arisen, because "...purists maintain that the natural acoustic sound of [Classical] voices [or] instruments in a given hall should not be altered."[14]

Kai Harada's article Opera's Dirty Little Secret[15] states that opera houses have begun using electronic acoustic enhancement systems "...to compensate for flaws in a venue's acoustical architecture." Despite the uproar that has arisen amongst operagoers, Harada points out that note of the opera houses using acoustic enhancement systems "...use traditional, Broadway-style sound reinforcement, in which most if not all singers are equipped with radio microphones mixed to a series of unsightly loudspeakers scattered throughout the theatre." Instead, most opera houses use the sound reinforcement system for acoustic enhancement, and for subtle boosting of offstage voices, onstage dialogue, and sound effects (e.g., church bells in Tosca or thunder in Wagnerian operas).

Acoustic enhancement systems include LARES (Lexicon Acoustic Reinforcement and Enhancement System) and SIAP, the System for Improved Acoustic Performance. These systems use microphones, computer processing "with delay, phase, and frequency-response changes", and then send the signal "... to a large number of loudspeakers placed in extremities of the performance venue." Another acoustic enhancement system, VRAS (Variable Room Acoustics System) uses "...different algorithms based on microphones placed around the room." The Deutsche Staatsoper in Berlin and the Hummingbird Centre in Toronto use a LARES system. The Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles, the Royal National Theatre in London, and the Vivian Beaumont Theatre in New York City use the SIAP system. [16]

Lecture halls and conference rooms

Lecture halls and conference rooms pose the challenge of reproducing speech clearly to a large hall, which may have reflective, echo-producing surfaces. In some conferences, sound engineers have to provide microphones for a large number of people, in the case of a panel conference or debate. In some cases, automatic mixers are used to control the levels of the microphones.

Rental systems

Audio visual (AV) rental systems have to be able to withstand heavy use, and even abuse from renters. For this reason, rental companies tend to own speaker cabinets which are heavily braced and protected with steel corners, and electronic equipment such as power amplifiers or effects are often mounted into protective road cases. As well, rental companies tend to select gear which has electronic protection features, such as speaker-protection circuitry and amplifier limiters.

As well, rental systems for non-professionals need to be easy to use and set up, and they must be easy to repair and maintain for the renting company. From this perspective, speaker cabinets need to have easy-to-access horns, speakers, and crossover circuitry, so that repairs or replacements can be made. Some rental companies often rent powered amplifier-mixers, mixers with onboard effects, and powered subwoofers for use by non-professionals, which are easier to set up and use.

Many Touring Acts and Large Venue Corporate events will rent large Sound Reinforcement Systems that typically include an Audio Engineer that is on staff with the renting company. In the case of rental systems for tours, there are typically several Engineers and Technicians from the Rental company that tour with the act to set up and calibrate the equipment for use by the band's production crew. The individual that actually mixes the act is often selected and provided by the band, as they are someone who has become familiar with the various aspects of the show and have worked with the act to establish a general idea of how they want the show to sound. The mixing engineer for an act sometimes also happens to be on staff with the rental company selected to provide the gear for the tour.

Live music clubs

Setting up sound reinforcement for live music clubs often poses unique challenges, because there is such a large variety of venues which are used as clubs, ranging from former warehouses or music theaters to small restaurants or basement pubs with concrete walls. In some cases, clubs are housed in multi-story venues with balconies or in "L"-shaped rooms, which makes it hard to get a consistent sound for all audience members. The solution is to use fill-in speakers to obtain good coverage, using a delay to ensure that the audience does not hear the same sound at different times.

Another problem with designing sound systems for live music clubs is that the sound system may need to be used for both prerecorded music played by DJs and live music. If the sound system is optimized for prerecorded DJ music, then it will not provide the appropriate sound qualities needed for live music, and vice versa. Lastly, live music clubs can be a hostile environment for sound gear, in that the air may be hot, humid, and smoky; in some clubs, keeping amplifiers cool may be a challenge.

Setting up and testing

Large-scale sound reinforcement systems are designed, installed, and operated by audio engineers and audio technicians. During the design phase of a newly constructed venue, audio engineers work with architects and contractors, to ensure that the proposed design will accommodate the speakers and provide an appropriate space for sound technicians and the racks of audio equipment. Sound engineers will also provide advice on which audio components would best suit the space and its intended use, and on the correct placement and installation of these components. During the installation phase, sound engineers ensure that high-power electrical components are safely installed and connected and that ceiling or wall mounted speakers are properly mounted (or "flown") onto rigging. When the sound reinforcement components are installed, the sound engineers test and calibrate the system so that its sound production will be even across the frequency spectrum.

System testing

A sound reinforcement system should be able to accurately reproduce a signal from its input, through any processing, to its output without any coloration or distortion. However, due to inconsistencies in venue sizes, shapes, building materials, and even crowd densities, this is not always possible without prior calibration of the system. This can be done in one of several ways.

The oldest method of system calibration involves a set of healthy ears, test program material (i.e. music or speech), a graphic equalizer, and last but certainly not least, a familiarity with the proper (or desired) frequency response. One must then listen to the program material through the system, take note of any noticeable frequency changes or resonances, and subtly correct them using the equalizer. Experienced engineers typically use a specific playlist of music every time they calibrate a system that they have become very familiar with. This process is still done by many engineers, even when analysis equipment is used, as a final check of how the system sounds with music or speech playing through the system.

A more objective method of manual calibration requires a pair of high-quality headphones patched into the input signal before any processing (such as the pre-fade-listen of the test program input channel of the mixing console, or the headphone output of the CD player or tape deck). One can then use this direct signal as a near-perfect reference with which to find any differences in frequency response. This method may not be perfect, but it can be very helpful with limited resources or time, such as using pre-show music to correct for the changes in response caused by the arrival of a crowd. [17]

Because this is still a very subjective method of calibration, and because the human ear is so dynamic in its own response, the program material used for testing should be as similar as possible to that for which the system is being used.

Since the development of digital signal processing (DSP), there have been many pieces of equipment and computer software designed to shift the bulk of the work of system calibration from human auditory interpretation to software algorithms that run on microprocessors.

One modern tool for calibrating a sound system using either DSP or Analog Signal Processing is a Real Time Analyzer (RTA). This tool is usually used by piping pink noise into the system and measuring the result with a special calibrated microphone connected to the RTA. Using this information, the system can be adjusted to help achieve the desired response. The displayed response from the RTA mic cannot be taken as a perfect representation of the room as the analysis will be different, sometimes drastically, when the mic is placed in different position in front of the system.

Some DSP system processing devices have been designed for use by non-professionals that automatically make adjustments in the system EQ based upon what is being read from the RTA mic. These are practically never used by professionals, as they almost never calibrate the system as well as a professional audio engineer can manually.

See also

- Public Address system (PA system)

References

- ^ Davis, Gary, and Ralph Jones. Sound Reinforcement Handbook. 2nd ed. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1989: 4.

- ^ Eargle, John, and Chris Foreman. Audio Engineering for sound reinforcement. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002. 299

- ^ Eargle, John, and Chris Foreman. Audio Engineering for sound reinforcement. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002. 167

- ^ Borgerson, Bruce. "Is it P.A. or SR?." Sound & Video Contractor. 1 November 2003. Prism Business Media. 18 February 2007 <http://svconline.com/mag/avinstall_pa_sr/index.html>.

- ^ http://psbg.emusician.com/ar/emusic_mixed_signals/index.htm "In addition to the main stereo bus, most mixers designed to work with multitrack recorders have four or more recording, or "group," buses. You can assign signals from one or more channel inputs to a single group bus and route them through that bus's output to a track input on the recorder (or anywhere else for that matter). The more buses you have, the more tracks you can record at the same time."

- ^ Eargle, John, and Chris Foreman. Audio Engineering for sound reinforcement. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002. 62

- ^ Badhorn, Philippe (February 2006). "Interview in Rolling Stone (France)". Rolling Stone.

- ^ What are Transducers?

- ^ The Monitor Engineer's Role in Performance by Philip Manor

- ^ Tech Tips: Advantages of a Dedicated Monitor Mixing Console 2004-02-16, Sweetwater Sound

- ^ Reverberation. Harmony-Central. Retrieved on January 23, 2009.

- ^ Concert Sound and Lighting Systems, Ch. 5, 'Power amplifiers', By John Vasey

- ^ a b "In-Ear Monitors: Tips of the Trade". Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ^ Sound Systems- Why?!

- ^ Entertainment Design, Mar 1, 2001 http://industryclick.com/magazinearticle.asp?releaseid=5643&magazinearticleid=66853&siteid=15&magazineid=138

- ^ Entertainment Design, Mar 1, 2001 http://industryclick.com/magazinearticle.asp?releaseid=5643&magazinearticleid=66853&siteid=15&magazineid=138

- ^ Rat, Dave. "When Hearing Starts To Drift". Retrieved 2007-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help)

- Davis, Gary, and Ralph Jones. Sound Reinforcement Handbook. 2nd ed. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1989.

- Eargle, John, and Chris Foreman. Audio Engineering for sound reinforcement. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002.

Further reading

Books

- AES Sound Reinforcement Anthology, Vols. 1 and 2, Audio Engineering Society, New York (1978 & 1996).

- Ahnert, W. & Steffer, F., Sound Reinforcement Engineering, SPON Press, London, 2000. ISBN 04-1921-810-6

- Alten, Stanley R. Audio in Media (5th ed.), Wadsworth, Belmont, CA (1999). ISBN 05-3454-801-6

- Ballou, Glen. Handbook for Sound Engineers, Third Edition. Oxford: Focal Press, 2005. ISBN 02-4080-758-8

- Benson, K. Audio Engineering Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988. ISBN 00-7004-777-4

- Borwick, J. (ed.), Loudspeaker and Headphone Handbook (3rd ed.), Focal Press, Boston 2001. ISBN 02-4051-578-1

- Brawley, J. (ed.), Audio systems Technology#2 - Handbook for Installers and Engineers, National Systems Contractors Association (NSCA), Cedar Rapids, IA. ISBN 07-9061-163-5

- Buick, Peter. Live Sound: PA for Performing Musicians, PC Publishing, Kent, UK 1996. ISBN 18-7077-544-9

- Colloms, Martin. High Performance Loudspeakers. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2005. ISBN 04-7009-430-3

- Davis, D. & C. Sound System Engineering, second edition, Focal Press, Boston 1997. ISBN 02-4080-305-1

- Dickason, V. The Loudspeaker Cookbook (5th ed.), Audio Amateur Press, Peterborough, NH 1995. ISBN 09-6241-917-6

- Eargle, J. Electroacoustical Reference Data, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston 1994. ISBN 04-4201-397-3

- Eargle J. Loudspeaker Handbook, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston 1997. ISBN 14-0207-584-7

- Eargle, J. The Microphone Book, Focal Press, Boston 2001. ISBN 02-4051-961-2

- Eiche, Jon F. The Yamaha Guide to Sound Systems for Worship, Hal Leonard Corp., Milwaukee, WI 1990. ISBN 07-9350-029-X

- Fry, Duncan. Live Sound Mixing (3rd ed.), Roztralia Productions, Victoria Australia 1996. ISBN 99-9635-270-6

- Giddings, Philip. Audio Systems Design and Installation (2nd ed.), Sams, Carmel, Indiana (1998). ISBN 06-7222-672-3

- JBL Professional, Sound System Design Reference Manual, Northridge, CA 1999. (ebook) [1]

- Langford-Smith, F. (Ed.), Radiotron Designers' Handbook, 4th ed., Amalgamated Wireless Valve Co. Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1952; CD-ROM, Old Colony Sound Labs, Peterborough, NH; reprinted as Radio Designer's Handbook, *Newnes, Butterworth-Heineman Ltd. 1997

- Moscal, Tony. Sound Check: The Basic of Sound and Sound Systems, Milwaukee, WI; Hal Leonard Corp. 1994. ISBN 07-9353-559-X

- Olson, H., Acoustical Engineering, D. Van Nostrand, New York 1947. Reprinted by Professional Audio Journals, Inc., Philadelphia 1991.

- Oson, H.F. Music, Physics and Engineering, Dover, New York 1967. ISBN 04-8621-769-8

- Pohlmann, Ken, Principles of Digital Audio (5th ed.), McGraw-Hill, New York 2005 ISBN 00-7144-156-5

- Stark, Scott H. Live Sound Reinforcement, Bestseller edition. Mix Books, Auburn Hills, MI 2004. ISBN 15-9200-691-4

- Streicher, Ron & F. Alton Everest. The New Stereo Soundbook (2nd ed.), Audio Engineering Associates, Pasadena, CA 1998. ISBN 09-6651-620-6

- Talbot-Smith, Michael (Ed.) Audio Engineer's Reference Book, 2nd ed. Focal Press, Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd. 2001. ISBN 02-4051-685-0

- Trubitt, David. Concert Sound: Tours, Techniques & Technology, Mix Books, Emeryville, CA 1993. ISBN 07-9352-073-8

- Trubitt, Rudy, Live Sound for Musicians, Hal Leonard Corp., Milwaukee, WI 1997. ISBN 07-9356-852-8

- Trynka, P. (Ed.), Rock Hardware, Blafon/Outline Press, London: Miller Freeman Press, San Francisco 1996. ISBN 08-7930-428-6

- Vasey, John. Concert Sound and Lighting Systems (3rd ed.) Focal Press, Boston 1999. ISBN 02-4080-364-7

- Whitaker, Jerry. AC Power Systems Handbook, Third Edition. Boca Raton: CRC, 2006. ISBN 08-4934-034-9

- Whitaker, Jerry and K. Benson. Standard Handbook of Audio and Radio Engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002. ISBN 00-7006-717-1

- White, Glenn and Gary J. Louie. The Audio Dictionary. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005. ISBN 02-9598-498-8

- White Paul, the Sound On Sound book of Live Sound for the Performing Musician, Sanctuary Publishing Ltd, London (2005).ISBN 18-6074-210-6

- Yakabuski, Jim, Professional Sound Reinforcement Techniques: Tips and Tricks of a Concert Sound Engineer, Mix Books, Vallejo, CA 2001. ISBN 08-7288-759-6

Papers

- Benson, J.E. "Theory and Design of Loudspeaker Enclosures", Amalgamated Wireless Australia Technical Review, (1968, 1971, 1972).

- Beranek, L., "Loudspeakers and Microphones", J. Acoustical Society of America, volume 26, number 5 (1954).

- Damaske, P., "Subjective Investigation of Sound Fields", Acustica, Vol. 19, pp. 198-213 (1967-1968).

- Davis, D & Wickersham, R., "Experiments in the Enhancement of the Artist's Ability to Control His Interface with the Acoustic Environment in Large Halls", presented at the 51st AES Convention, 13-16 May 1975; preprint number 1033.

- Eargle J. & Gelow, W., "Performance of Horn Systems: Low-Frequency Cut-off, Pattern Control, and Distortion Trade-offs", presented at the 101st Audio Engineering Society Convention, Los Angeles, 8-11 November 1996. Preprint number 4330.

- Engebretson, M., "Low Frequency Sound Reproduction", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 32, number 5, pp. 340-352 (May 1984)

- French, N. & Steinberg, J., "Factors Governing the Intelligibility of Speech Sounds", J. Acoustical Society of America, volume 19 (1947).

- Gander, M. & Eargle, J., "Measurement and Estimation of Large Loudspeaker Array Performance", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 38, number 4 (1990).

- Henricksen, C. & Ureda, M., "The Manta-Ray Horns", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 26, number, pp. 629-634 (September 1978).

- Hilliard, J., "Historical Review of Horns Used for Audience-Type Sound Reproduction", J. Acoustical Society of America, volume 59, number 1, pp. 1 - 8, (January 1976)

- Houtgast, T. and Steeneken, H., "Envelope Spectrum Intelligibility of Speech in Enclosures", presented at IEEAFCRL Speech Conference, 1972.

- Klipsch, P. "Modulation Distortion in Loudspeakers: Parts 1, 2, and 3" J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 17, number 2 (April 1969), volume 18, number 1 (February 1970), and volume 20, number 10 (December 1972).

- Lochner, P. & Burger, J., "The Influence of Reflections on Auditorium Acoustics", Sound and Vibration, volume 4, pp. 426-54 (196).

- Meyer, D., "Digital Control of Loudspeaker Array Directivity", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 32, number 10 (1984).

- Peutz, V., "Articulation Loss of Consonants as a Criterion for Speech Transmission in a Room", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 19, number 11 (1971).

- Rathe, E., "Note on Two Common Problems of Sound Reproduction", J. Sound and Vibration, volume 10, pp. 472-479 (1969).

- Schroeder, M., "Progress in Architectural Acoustics and Artificial Reverberation", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 32, number 4, p. 194 (1984)

- Smith, D., Keele, D., and Eargle, J., "Improvements in Monitor Loudspeaker Design", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 31, number 6, pp. 408-422 (June 1983).

- Toole, F., "Loudspeaker Measurements and Their Relationship to Listener Preferences, Parts 1 and 2", J. Audio Engineering Society, volume 34, numbers 4 & 5 (1986).

- Veneklasen, P., "Design Considerations from the Viewpoint of the Consultant", Auditorium Acoustics, pp.21-24, Applied Science Publishers, London (1975).

- Wente, E. & Thuras, A., "Auditory Perspective — Loudspeakers and Microphones", Electrical Engineering, volume 53, pp.17-24 (January 1934). Also, BSTJ, volume XIII, number 2, p. 259 (April 1934) and Journal AES, volume 26, number 3 (March 1978).