Collectivization in the Soviet Union: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Trey Stone (talk | contribs) let it be known that i will shoot any vandal in sight. like a kulak. |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

In the [[Soviet Union]], [[collectivization|collectivisation]] was a policy introduced in the late [[1920s]], of consolidation of individual land and labour into co-operatives called '''collective farms''' ([[Russian language|Russian]]: '''колхоз''', '''[[kolkhoz]]''') and '''state farms''' ([[sovkhoz]]es) with the goals to increase the agricultural production, to put it under the control of the state, as well as an important political goal, a step towards [[communism]]: transfer of the land and agricultural property from [[kulak]]s to collectives of peasants. |

In the [[Soviet Union]], [[collectivization|collectivisation]] was a policy introduced in the late [[1920s]], of consolidation of individual land and labour into co-operatives called '''collective farms''' ([[Russian language|Russian]]: '''колхоз''', '''[[kolkhoz]]''') and '''state farms''' ([[sovkhoz]]es) with the goals to increase the agricultural production, to put it under the control of the state, as well as an important political goal, a step towards [[communism]]: transfer of the land and agricultural property from [[kulak]]s to collectives of peasants. |

||

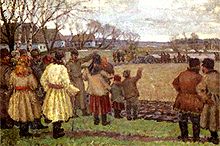

[[Image:Collectivization-get-rid-of-kulak.jpg|300px|right|thumb| |

[[Image:Collectivization-get-rid-of-kulak.jpg|300px|right|thumb|The collectivisation campaign in the USSR, 1930s. The slogan reads: "We kolkhoz farmers are liquidating the kulaks as a class, on the basis of complete collectivisation."]] |

||

==Traditional farming== |

==Traditional farming== |

||

Revision as of 06:18, 15 December 2004

In the Soviet Union, collectivisation was a policy introduced in the late 1920s, of consolidation of individual land and labour into co-operatives called collective farms (Russian: колхоз, kolkhoz) and state farms (sovkhozes) with the goals to increase the agricultural production, to put it under the control of the state, as well as an important political goal, a step towards communism: transfer of the land and agricultural property from kulaks to collectives of peasants.

Traditional farming

In Imperial Russia, the Stolypin Reform was aimed at the development of capitalism in agriculture by giving incentives for creation of large farms. The World War I and the following Russian Revolution stopped this process in Russia. During the revolution, large holdings of agricultural land were seized by the peasants and repartitioned, according to one of the revolutionary slogan "Land — to Peasants". The land seized from landlords and kulaks had before the revolution produced 70% of the grain which entered the market and was available for export. Before the revolution peasants controlled only 210 million hectares in 16 million holding, after, 314 million hectares in 25 million holdings. Before the revolution peasants produced 50% of the food grown in Russia and consumed 60%; after, they produced 85% but consumed 80% of what they grew. Thus the problem of devising some method of getting grain into the market and available for export.

Although conditions varied over the vast expanse of the Soviet Union and among ethnic groups and enclaves, farming on the most territory of the European part of the state and in Siberia was carried on by a host of individual small landowners who lived ether at isolated settlements (khutors) or in villages. Farmland was characteristically laid out in strips divided by boundary ridges and dead furrows, and could be worked by small horse-drawn equipment, but not by modern tractors. Richer peasants might own 2 or 3 horses, 4 or more cows and work 30 or 40 acres (120,000 or 160,000 m²) of land with the help of seasonal employees. The poorest peasants often could not afford a single horse.

The cities' need for food

The World War I, Revolution and subsequent Civil War disrupted farming and food distribution in Russia. Because of the collapse of industrial production and the monetary system, there was little incentive for farmers to sell their products. The money was, in their view, no good, and in any event there was little available to buy. During the Civil War the authorities resorted to the policy of war communism. In agriculture, it amounted to food requisition according to state-defined quotas (продразверстка), with the leaders of a community often held hostage pending delivery of food. The New Economic Policy (NEP) replaced requisitions by a foodstuffs tax (продналог); however, it turned out to favor the capitalistic sector of the peasantry, known as kulaks, an undesirable outcome from the communist point of view.

The crisis of 1928

Later analysts have identified a grain procurement crisis which occured in early 1928 (involving the harvest of 1927) as the source of the perception by the leadership that a crisis existed in agriculture. Stalin put the blame on kulaks who he believed had sabotaged grain collection. There was a failure, by 2 million tons, to purchase sufficient grain at the price set by the state. The grain had been produced but was being stored. Rather than raise the price, the Politburo adopted a emergency measure which required requisition of grain. 2.5 million tons were seized.

The seizures of grain discouraged the peasants and less grain was produced during 1928 and again requsition was resorted to, much of the grain being requisitioned from middle peasants as sufficient quantities were not in the hands of the kulaks. In 1929 resistance became general with some terrorist incidents but also massive hiding (burial was the common method) and illegal transfers of grain by kulaks. What they could not hide or otherwise dispose of they harvested as hay, burned or threw into the rivers.

Faced with the collapse of the agricultural sector, a decision was made at a plenum of the Central Committee in November, 1929 to embark on a nationwide program of collectivisation. Collectivisation had been encouraged since the revolution, but only 2% of households belonged to them by 1928. The situation represented to the plenum was somewhat misrepresented by Stalin and Molotov who greatly exaggerated the willingness of the peasants to reorganize as collectives, a campaign of voluntary collectivisation having succeeded by November, 1929 in involving only 7.6% of households.

Stalin predicted, "Our country will, in some three years time, have become one of the richest grainaries, if not the richest, in the whole world." Later observers, generally critical, have come to the conclusion that the crisis could have been avoided by better pricing, instituting a reliable market mechanism, and increase in productivity of the existing small farms.

Goals of collectivisation

Collectivisation sought to modernise Soviet agriculture, consolidating the land into parcels that could be farmed by modern equipment using the latest scientific methods of agriculture. In fact, an American Fordson tractor (called "Фордзон" in Russian) was the best propaganda in favor of collectivisation.

Social and ideological goals would also be served though mobilisation of the peasants in a co-operative economic enterprise which could serve a secondary purpose of providing social services to the people.

It was hoped that the goals of collectivisation could be achieved voluntarily. When collectivisation failed to attract the number of peasants hoped, the government resorted to forceful implementation of the plan.

Given the goals of the First Five Year Plan, the state sought increased political control of agriculture, hoping to feed the rapidly growing urban areas and to export grain, a source of foreign currency needed to import technologies necessary for heavy industrialisation.

Implementation

Theoretically, landless peasants were to be the biggest beneficiaries from collectivisation, because it promised them an opportunity to take an equal share in labour and its rewards. For those with property, however, collectivisation meant giving it up to the collective farms and selling most of the food that they produced to the state at low prices set by the state itself, so they were opposed to the idea. Furthermore, collectivisation involved significant changes in the traditional village life of Russian peasants within a very short timeframe, despite the long Russian rural tradition of collectivism in obshchinas. The changes were even more dramatic in other places, such as in Ukraine, with its tradition of individual farming, in the Soviet republics of Central Asia, and in the trans-Volga steppes, where for a family to have a herd of livestock was not only a matter of sustenance, but of pride as well.

Due to the aforementioned factors and a number of others, opposition to collectivisation proved to be widespread among the wealthier Soviet rural population. Therefore less radical forms of collective farming were also implemented, such as agricultural cooperatives, as well as agricultural associations, known as "Associations for Joint Tillage of Land" (Товарищество по совместной обработке земли, ТОЗ). Also, various cooperatives for processing of agricultural products were installed.

However in November 1929, the Central Committee decided to implement forced collectivisation. This marked the end of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which had allowed peasants to sell their surpluses on the open market. Grain requisitioning intensified, and wealthy peasants were forced to join the collective farms, giving up their private plots of land. In response to this, many such peasants initiated an armed resistance. As a form of protest, many of the targeted peasants preferred to slaughter their animals for food rather than give them over to collective farms, which produced a major reduction in livestock.

To assist collectivisation, the Party decided to send 25,000 "socially conscious" industry workers to the countryside. This was accomplished during 1929–1933, and these workers have become known as twenty-five-thousanders ("dvadtsatipyatitysyachniki"). Shock brigades were used to force reluctant peasants into joining the collective farms and remove those who were declared kulaks and "kulaks' helpers".

The price of collectivisation was so high that the March 2, 1930, issue of Pravda contained Stalin's article Dizzy with success, in which he discouraged overzealousness:

- "It is a fact that by February 20 of this year 50 per cent of the peasant farms throughout the U.S.S.R. had been collectivised. That means that by February 20, 1930, we had overfulfilled the five-year plan of collectivisation by more than 100 per cent... some of our comrades have become dizzy with success and for the moment have lost clearness of mind and sobriety of vision."

After the publication of the article, the pressure for collectivisation temporarily decreased and peasants started leaving collective farms. According to Martin Kitchen, the number of members of collective farms dropped by 50% in 1930. But soon collectivisation intensified, and by 1936, about 90% of Soviet agriculture was collectivised. Due to high government quotas, farmers often got less for their labor than they did before collectivisation, and some refused to work. In many cases, the immediate effect of collectivisation was to reduce grain output and almost halve livestock.

Despite the initial plans, collectivisation, accompanied by the bad harvest of 1932–1933, did not rise to expectations. The CPSU blamed these problems in food production on kulaks (Russian: fist; prosperous peasants), who were organising resistance to collectivisation. Indeed, some kulaks had been hoarding grain in order to speculate on higher prices. The term "kulak" also came to be used loosely to describe anyone who opposed collectivisation, which included many peasants who were anything but rich.

Many peasants, notably the kulaks, opposed collectivization. Acts of sabotage included burning of crops and slaughtering draught animals. There were also some cases of destruction of property, and attacks on officials and members of the collectives. Isaac Mazepa, leader of the anti-Soviet Ukrainian Nationalist movement, boasted of "[t]he catastrophe of 1932", the result of "passive resistance … which aimed at the systematic frustration of the Bolsheviks' plans for the sowing and gathering of the harvest". In his words, "[w]hole tracts were left unsown, [and as much as] 50 per cent [of the crop] was left in the fields, and was either not collected at all or was ruined in the threshing".

The Soviet government responded to these acts of sabotage and opposition by cutting off food supply to kulaks and areas where there was opposition to collectivization, especially in the Ukrainian region. The sabotage of the kulaks and other factors led to what is refered to by some Ukrainan historians as Holodomor. Some kulak saboteurs and some who opposed collectivization were executed or sent to forced-labour camps. Most expropriated kulaks were resettled in Siberia and Kazakhstan and a significant number died on the way.

On August 7, 1932, the Ukase about the Protection of Socialist Property proclaimed that the punishment for "any sabotage (вредительство) or theft of communal property" ranged from ten years of incarceration up to the death sentence. With what some called the Law of Spikelets ("Закон о колосках"): peasants (including children) who hand-collected grains in the collective fields after the harvest were arrested for damaging the state grain production. Martin Amis writes in Koba the Dread that the number of sentences for this particular offence in the bad harvest period from August 1932 to December 1933 was 125,000.

Ukraine

Most historians agree that the disruption caused by collectivisation and the resistance to it by kulaks and some other peasants worsened conditions during the bad harvest of 1932-1933, especially in Ukraine. Planned harvest quotas for Ukraine were being gradually raised from year to year. Although for the affected years they were lowered by 20% (from around 6.8 mln tonnes to 4.6 mln tonnes), they remained unreachable. A drought and outbreak of typhoid hurt the harvest as well. This, in addition with cutting off supplies to the rich peasants who destroyed their crops and grain as acts of resistance, and cutting off supplies to some areas in general resulted in the 1932-1933 famine reffered to in Ukraine as the 'Holodomor (literally "famine pestilence").

About 40 million people were affected by the food shortages, including areas near Moscow. The center of the bad harvest, however, was in Ukraine and surrounding regions including the Don, the Kuban, the Northern Caucasus and Kazakhstan.

Some Ukrainian scholars characterize the bad harvest as "a genocide of the Ukrainian people". Blame for the underfulfilment of plans of grain acquisition was put by the Soviet government on kulaks and "bourgeois nationalist elements", which was followed by purges of Ukrainian management, communist party cadre, and intelligentsia. Drought and a typhoid epidemic also contributed to the bad harvest.

Beyond Nazi Germany, there was not much coverage of the bad harvest as anything but a bad harvest. The New York Times denied Goebbels assertions that some type of genocide was going on. Media coverage of the 1932-1933 famine in Ukraine has been the subject of some controversy. While the contemporary world press—most famously, the New York Times—did in fact deny reports of famine, critics contend that this was due to a number of political factors: Soviet media censorship, difficulty of travel in the affected regions and Western efforts to appease Stalin. Since the 1980s, however, New York Times management has said that dispatches from their Moscow correspondent at the time, Pulitzer Prize winner Walter Duranty, were based primarily on Soviet propaganda and subsequently seriously flawed.

Robert Conquest, Nicolas Werth and the 1988 United States Congress Commission on the Ukraine Famine report that 6 million people died in the bad harvest. This number is disputed by some communists and anti-anti-communists, who claim much of the evidence is politically-motivated anti-Soviet propaganda tracing back to Joseph Goebbels and Ukranian Nazi collaborators. For example, Robert Conquest cited Black Deeds of the Kremlin, 55 times as a source for estimations on the death toll in Ukraine, and the subsequent estimations by Werth and the congressional committee relied heavily on Conquest's work.

In 1983 Sergei Maksudov, a Russian demographer, having compared results of censuses and taken migration into account, estimated that there were no less than 4.5 million unnatural deaths in Ukraine between 1927 and 1938 (due to collectivization, dekulakization and purges).

Some communists such as Jeff Coplon and Ludo Martens have recently claimed a much more modest figure of between several hundred thousand and two million deaths.

This uncertainty as to the death toll of collectivization is reflected in the words of Nikita Khrushchev: Perhaps we'll never know how many people perished directly as a result of collectivisation, or indirectly as a result of Stalin's eagerness to blame his failure on others.

Glasnost and Ukrainian independence

With the advent of glasnost, the Great Famine became a subject of general discussion in Ukraine after having been long suppressed by Soviet authorities. Rukh and its leader Mikhailo Boichyhyn engaged in a series of actions, including a commemoration of what they termed "the genocide", in the village of Targon. A platform was built over the burial mounds of some of the victims of the famine; consulting with the elderly, a list of 360 victims was compiled and published in the newspaper Literaurnaya Ukraina, and a memorial service held which attracted national attention and significantly strengthened the independence movement.

References and further reading

- Ammende, Ewald, "Human life in Russia", (Cleveland: J.T. Zubal, 1984), Reprint, Originally published: London, England: Allen & Unwin, 1936, ISBN 0939738546

- Robert Conquest The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine, Oxford University Press, October 1986, hardcover, ISBN 0888641109; trade paperback, Oxford University Press, November, 1987, ISBN 0195051807; hardcover, ISBN 0195040546

- R. W. Davies, The Socialist Offensive (Volume 1 of The Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard University Press (1980), hardcover, ISBN 0674814800

- R. W. Davies, The Soviet Collective Farm, 1929-1930 (Volume 2 of the Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard University Press (1980), hardcover, ISBN 0674826000

- R. W. Davies, Soviet Economy in Turmoil, 1929-1930 (volume 3 of The Industrialization of Soviet Russia), Harvard University Press (1989), ISBN 0674826558

- R. W. Davies and Stephen G. Wheatcroft, Years of Hunger: Soviet Agriculture, 1931-1933, (volume 4 of The Industrialisation of Soviet Russia), Palgrave Macmillan (April, 2004), hardcover, ISBN 0333311078

- R. W. Davies and S. G. Wheatcroft, Materials for a Balance of the Soviet National Economy, 1928-1930, Cambridge University Press (1985), hardcover, 467 pages, ISBN 0521261252

- Miron Dolot, Execution by Hunger: The Hidden Holocaust, W. W. Norton (1987), trade paperback, 231 pages, ISBN 0393304167; hardcover (1985), ISBN 0393018865

- Maurice Hindus, Red Bread: Collectivization in a Russian Village, Indiana University Press, 1988, hardcover, ISBN 0253349532; trade paperback, Indiana University Press, 1988, 372 pages, ISBN 0253204852; earlier editions dating from 1931 are available at used book sellers.

- International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine. "Final report", [Jacob W.F. Sundberg, President], 1990. [Proceedings of the International Commission of Inquiry and its Final report are in typescript, contained in 6 vols. Copies available from the World Congress of Free Ukrainians, Toronto].

- Moshe Lewin, Russian Peasants and Soviet Power: A Study of Collectization, W.W. Norton (1975), trade paperback, ISBN 0393007529

- Ludo Martens, Un autre regard sur Staline, Éditions EPO, 1994, 347 pages, ISBN 2872620818. See the section "External links" for an English translation.

- Nancy Nimitz. "Farm Development 1928–62", in Soviet and East European Agricultures, Jerry F. Karcz, ed. Berkeley, California (US): University of California, 1967.

- "Famine in the Soviet Ukraine 1932-1933: a memorial exhibition", Widener Library, Harvard University, prepared by Oksana Procyk, Leonid Heretz, James E. Mace. -- (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard College Library, distributed by Harvard University Press, 1986), ISBN 0674294262

- David Satter, Age of Delirium : The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Union, Yale University Press (1996), hardcover, 424 pages, ISBN 0394529340

- The Russians Hedrick Smith (1976) ISBN 0812905210

- Douglas Tottle. Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian genocide myth from Hitler to Harvard. Toronto: Progress Books, 1987. ISBN 0919396518.

- The Second Socialist Revolution, Tatyana Zaslavskaya, ISBN 0253206146 (a survey by a Soviet sociologist written in the late 1980s which advocated restructuring of the economy)

- Sally J. Taylor, Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty : The New York Times Man in Moscow, Oxford University Press (1990), hardcover, ISBN 0195057007

- United States, "Commission on the Ukraine Famine. Investigation of the Ukrainian Famine, 1932-1933: report to Congress / Commission on the Ukraine Famine", [Daniel E. Mica, Chairman; James E. Mace, Staff Director]. -- (Washington D.C.: U.S. G.P.O.: For sale by the Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1988), (Shipping list: 88-521-P).

- United States, "Commission on the Ukrainian Famine. Oral history project of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine", James E. Mace and Leonid Heretz, eds. (Washington, D.C.: Supt. of Docs, U.S. G.P.O., 1990), ISBN 0160262569

- InfoUkes Famine resource page

Related articles

External links

- Ukrainian Famine: Excerpts from the Original Electronic Text at the web site of Revelations from the Russian Archives

- "Soviet Agriculture: A critique of the myths constructed by Western critics", by Joseph E. Medley, Department of Economics, University of Southern Maine (US).

- "The Ninth Circle", by Olexa Woropay

- Prize-winning essay on FamineGenocide.com

- 1932-34 Great Famine: documented view by Dr. Dana Dalrymple