Silent Sam: Difference between revisions

Add sources for text of speeches from UNC archive project. ce |

Add Carr trustee source |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2018/08/22/scholars-explain-the-racist-history-of-uncs-silent-sam-statue/amp/}}</ref> |

|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinakillgrove/2018/08/22/scholars-explain-the-racist-history-of-uncs-silent-sam-statue/amp/}}</ref> |

||

Establishing a [[American Civil War|Civil War]] monument at a Southern university became a goal of the North Carolina division of the [[United Daughters of the Confederacy]] (UDC) in 1907. UNC approved the group's request in 1908 and thus, with funding from UNC alumni and the UDC, Wilson designed the statue, using a young Boston man as his model. At the unveiling on June 2, 1913, local industrialist [[Julian Carr (industrialist)|Julian Carr]] gave a speech espousing [[white supremacy]].<ref name=Topple/> Other speeches by Governor Locke Craig,<ref>https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/e1994bf342e4786f24b9ba5df3818e0a.pdf</ref> UNC President Francis Venable<ref>https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/225998</ref><ref>https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/226008</ref> and members of the [[United Daughters of the Confederacy|UDC]]<ref>https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/3333889eb89e79aabbeb85298a8960db.pdf</ref> noted the students' sacrifice during the war.<ref>"Monument to University's Soldier Sons Unveiled at Chapel Hill," ''Charlotte Observer'' (Charlotte, NC) June 3, 1913 (GenealogyBank) [https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/newspapers/image/v2:11260DC9BB798E30@GB3NEWS-113ACC1F2FF5E0B8@2419922-113ACC1F427B5C58@0]</ref><ref>https://www.newsobserver.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/past-times/article22788855.html</ref> |

Establishing a [[American Civil War|Civil War]] monument at a Southern university became a goal of the North Carolina division of the [[United Daughters of the Confederacy]] (UDC) in 1907. UNC approved the group's request in 1908 and thus, with funding from UNC alumni and the UDC, Wilson designed the statue, using a young Boston man as his model. At the unveiling on June 2, 1913, local industrialist and UNC Trustee [[Julian Carr (industrialist)|Julian Carr]] gave a speech espousing [[white supremacy]].<ref name=Topple/><ref>https://patch.com/north-carolina/charlotte/silent-sam-confederate-statue-be-reinstalled-unc-official</ref> Other speeches by Governor Locke Craig,<ref>https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/e1994bf342e4786f24b9ba5df3818e0a.pdf</ref> UNC President Francis Venable<ref>https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/225998</ref><ref>https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/226008</ref> and members of the [[United Daughters of the Confederacy|UDC]]<ref>https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/3333889eb89e79aabbeb85298a8960db.pdf</ref> noted the students' sacrifice during the war.<ref>"Monument to University's Soldier Sons Unveiled at Chapel Hill," ''Charlotte Observer'' (Charlotte, NC) June 3, 1913 (GenealogyBank) [https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/newspapers/image/v2:11260DC9BB798E30@GB3NEWS-113ACC1F2FF5E0B8@2419922-113ACC1F427B5C58@0]</ref><ref>https://www.newsobserver.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/past-times/article22788855.html</ref> |

||

Beginning in the 1960s, ''Silent Sam'' (a name that first appeared the previous decade) faced opposition on the grounds of its racial message, and calls to remove the monument reached a higher profile in the late 2010s. In 2017 UNC Chancellor [[Carol Folt|Carol L. Folt]] said that she would remove the statue if this was not prohibited by a 2015 state law; during the 2017–18 year UNC spent $390,000 on security for the statue. |

Beginning in the 1960s, ''Silent Sam'' (a name that first appeared the previous decade) faced opposition on the grounds of its racial message, and calls to remove the monument reached a higher profile in the late 2010s. In 2017 UNC Chancellor [[Carol Folt|Carol L. Folt]] said that she would remove the statue if this was not prohibited by a 2015 state law; during the 2017–18 year UNC spent $390,000 on security for the statue. |

||

Revision as of 16:49, 4 September 2018

| Silent Sam | |

|---|---|

Silent Sam in 2007 | |

| Location | University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States |

| Coordinates | 35°54′50.22″N 79°3′8.55″W / 35.9139500°N 79.0523750°W |

| Dedicated | June 2, 1913 |

| Sculptor | John A. Wilson |

Silent Sam is a bronze statue of a Confederate soldier by sculptor John A. Wilson, which stood from 1913 until 2018 on the historic upper quad of the University of North Carolina (UNC) in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States. Its location on McCorkle Place, at the main entrance to the university, was described as "a place of honor".[1][2]

Establishing a Civil War monument at a Southern university became a goal of the North Carolina division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) in 1907. UNC approved the group's request in 1908 and thus, with funding from UNC alumni and the UDC, Wilson designed the statue, using a young Boston man as his model. At the unveiling on June 2, 1913, local industrialist and UNC Trustee Julian Carr gave a speech espousing white supremacy.[3][4] Other speeches by Governor Locke Craig,[5] UNC President Francis Venable[6][7] and members of the UDC[8] noted the students' sacrifice during the war.[9][10]

Beginning in the 1960s, Silent Sam (a name that first appeared the previous decade) faced opposition on the grounds of its racial message, and calls to remove the monument reached a higher profile in the late 2010s. In 2017 UNC Chancellor Carol L. Folt said that she would remove the statue if this was not prohibited by a 2015 state law; during the 2017–18 year UNC spent $390,000 on security for the statue.

On August 20, 2018, protesters toppled Silent Sam and university authorities hauled it away in a dump truck.[3][11][2] UNC later said its location was being kept hidden for safety reasons.[12] On August 24, Chancellor Folt told reporters that there were no concrete plans for what to do next with the statue.[13] On August 31, she issued a statement saying Silent Sam's original location was "a cause for division and a threat to public safety," and that she wanted to move the Confederate monument to another part of campus. "The university system’s Board of Governors gave approval earlier this week to seek a 'safe, legal and alternative' location for the monument, Dr. Folt said, adding that she is seeking input from students, staff and alumni — as well as state legislators and the governor — to decide where it should go."[14]

Early history, 1909–1913

Campaign

During the American Civil War, over 1,000 students and employees of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) enlisted with either army.[15] Out of all enlisted from the university, 287 lost their lives.[16] University president David Lowry Swain was able to keep the university open throughout the war, educating the few students too young to enlist, exempt because of ill health, or discharged because of war injuries ,[17] though those students and faculty eligible to serve did so.[18]

In 1907, the North Carolina chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) decided that its next major goal was to "be the erection, on the campus at the State University, of a monument to the students and faculty, who went out from its walls in 1861 to fight and die for the South."[19]Later meetings described the belief that UNC students and employees who served in either army "are worthy of a monument" which "should ever be before the eyes of the present-day students".[15] The request for a monument was presented to, and approved by, the UNC board of trustees on June 1, 1908.[20]

The monument was funded by the university, alumni, and the UDC. UNC and the UDC spent until 1913 fundraising the $7,500[a] that Canadian sculptor John Wilson charged for the statue,[22] which he discounted from his asking price of $10,000.[15][23] The Daughters originally were slated to give $1,500 of the cost of the statue,[15] though their success at fundraising lead the university to ask for them to cover $2,500 by 1911.[23] Most of the rest of the cost was covered by alumni donations, with the exception of $500 the university eventually had to give to reach the contracted total of $7,500.[23] The statue was planned to be in place for the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Civil War in 1911,[15] but raising funds to pay for the statue delayed the project by two years.[23]

Design

In a manner similar to his earlier Daniel A. Bean sculpture, John A. Wilson created a "silent" statue by not including a cartridge box on the subject's belt so he cannot fire his gun.[24] Like the earlier sculpture, Wilson used a northerner—Harold Langlois of Boston—as his model.[22] This was part of a tradition of "Silent Sentinels;" statues created in the North, often mass-produced, depicting soldiers without ammo or with their guns at parade rest.[25] As with these other statues, this memorial was positioned to face north, towards the Union.[22]

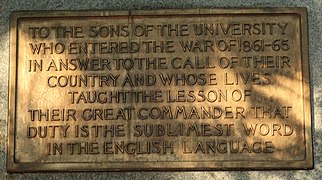

A bronze plaque in bas-relief on the front of the memorial's base depicts a woman, representing the state of North Carolina, convincing a young student to fight for the Southern cause as he drops his books, representing students leaving their studies.[26] A small bronze inscription plaque on the left side of the base says,[b] "Erected under the auspices of the North Carolina division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy aided by the alumni of the university". Another bronze inscription plaque on the right reads,[b] "To the sons of the university who entered the War of 1861–65 in answer to the call of their country and whose lives taught the lesson of their great commander that duty is the sublimest word in the English language".[27][c]

- Pedestal plaques

-

Left side

-

Front

-

Right side

Dedication

The program for the unveiling of the monument started at 3:30 pm, on June 2, 1913. Speeches were given by, among others, Mrs. Marshall Williams, president of the local division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy; and Francis Preston Venable, the university’s president. The program concluded with a rendition of "Tenting on the Old Camp Ground".[29]

"The University mourned in silent desolation. Her children had been slain. But she was splendid in that day of tribulation, for wherever armies had marched and wherever the conclusion of fierce battle had been tried, her sons had fought and fallen at the front. This statue is a memorial to their chivalry and devotion. It is an epic poem in bronze. Its beauty and its grandeur are not limited by the genius of the sculptor. The soul of the beholder will determine the revelation of its meaning. It will remind you, and those who come after you of the boys who left these peaceful classic shades for the hardships of armies at the front, for the fierce carnage of titanic battles, for suffering and for death. We unveil and dedicate this monument today, as a covenant that we, too, will do our task with fidelity and courage." -from the dedication speech of Governor Locke Craig, June 2, 1913 [30]

The Governor of North Carolina, Locke Craig, also spoke. "Ours is the task to build a State worthy of all patriotism and heroic deeds," he said, "a State that demands justice for herself and all her people, a State sounding with the music of victorious industry, a State whose awakened conscience shall lead the State to evolve from the forces of progress a new social order, with finer development for all conditions and classes of our people".[31]

The dedication speech which has attracted the most subsequent notice was given by Julian Carr, a prominent industrialist, UNC alumnus, former Confederate soldier, and the largest single donor towards the construction of the monument.

W. Fitzhugh Brundage, the William B. Umstead Professor of History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, described this speech as one in which Carr "unambiguously urged his audience to devote themselves to the maintenance of white supremacy with the same vigor that their Confederate ancestors had defended slavery."[32] In it, Carr emphatically praised the student-soldiers and soldiers of the Confederate Army for their wartime valor and patriotism,[3] adding that "the present generation ... scarcely takes note of what the Confederate soldier meant to the welfare of the Anglo Saxon race during the four years immediately succeeding the war ... Their courage and steadfastness saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the South."

According to Brundage, Carr's phrase "the four years immediately succeeding the war" is a clear reference to the Reconstruction era, when the Ku Klux Klan, working to restore the dominance of traditional white hierarchy in the South, terrorized blacks and white Republicans.[32] Later in the speech Carr boasted:

One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds because she had maligned and insulted a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison.[32]

In 2009, Carr's speech was rediscovered in the university archives by then-graduate student in history Adam Domby.[3] Domby included the above quotation in a letter to The Daily Tar Heel, the campus newspaper, in 2011.[33] Carr's speech was later publicized by activists campaigning for the statue's removal.[3]

Later reactions

20th century

The statue was originally called "Soldiers Monument" but was also referred to as the "Confederate memorial" from the 1920s through the 1940s.[34] The name "Silent Sam" was first cited in 1954, in the campus newspaper The Daily Tar Heel.[34] A story developed around the statue that "Sam" would fire his gun if a virgin walked by; in 1937, this story was called an "old local wisecrack".[34]

The monument has been a subject of controversy and a site of protest since the 1960s. In March 1965, a discussion about the monument's meaning and history occurred in the letters to the editor of the UNC student newspaper, the Daily Tar Heel.[20] In May 1967, poet John Beecher "debated" Silent Sam, reading to the statue from his book of poetry To Live and Die in Dixie. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr in April 1968, the monument was vandalized.[20][35] In the early 1970s, the monument was the site of several demonstrations by the Black Student Movement.[20] Students gathered by the statue to speak out after Los Angeles police officers were found not guilty in the 1992 Rodney King trial.[36] In 1997, a Martin Luther King Jr. Day march focusing on issues facing UNC housekeepers ended at the monument.[20]

21st century

Several protests in the late 2010s were directed toward the statue with calls for its removal.

In July 2015, the statue was vandalized during a wave of vandalism targeting Confederate monuments.[37] A UNC history professor, Dr. Harry Watson, said that he believed the monument represented an important part of history but that its glorification promoted a false conception of the Civil War.[38] In late July 2015, the North Carolina General Assembly passed SL 2015–170, the "Cultural History Artifact Management and Patriotism Act of 2015", which forbids permanent removal of public objects of remembrance, unless they are threats to public safety or they cannot be preserved at their current location. It also mandates that any alteration or relocation of these objects must be approved by the North Carolina Historical Commission, and puts further restrictions on where these objects may be relocated.[39]

In August 2017, following the Charlottesville incidents, hundreds gathered around the statue to call for its removal.[40] University officials evaluated state law to determine if that was possible, while state lawmakers argued that SL 2015–170 prohibited such action.[41] Later that month, shortly after the Confederate Soldiers Monument in Durham was toppled, hundreds of protesters gathered at the statue calling for its removal, and thousands signed a change.org petition to remove it.[42]

On August 21, 2017, UNC chancellor Carol Folt, UNC president Margaret Spellings, UNC board-of-governors chairman Lou Bissette, and UNC trustee chairman Haywood Cochrane wrote to Governor Roy Cooper,[43] warning of "significant safety and security threats" [44] concerning Silent Sam: "it is only a matter of time before an attempt is made to pull down Silent Sam in much the same manner we saw in Durham ... An attempt may occur at any time."[45] Folt stated that if UNC could remove the statue, it would, but was prohibited by SL 2015–170.[46][42][47] Cooper responded to Spellings, saying UNC could remove the statue if there was "a real risk to public safety."[42] Folt replied that despite the governor's statement, the university had to follow the 2015 law.[44][48]

UNC had begun developing alternate signs and an interactive tour meant to place Silent Sam in context and tell the "true" history of UNC.[46] From July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018, UNC spent $390,000 on security for the monument. Of that, $3,000 was for cleaning the monument. The $387,000 remainder was spent on law enforcement personnel costs.[44]

Toppling, 2018

On the night of August 20, 2018, the day before the 2018–19 school year began, protestors toppled the statue. [11] A protest event with speakers began at 7 p.m., in opposition to white supremacism and to support doctoral student Maya Little who, in April 2018, splashed red paint mixed with her own blood on the statue.[49][50] In a speech at the protest, Little said, "It's time to tear down Silent Sam. It's time to tear down UNC's institutional white supremacy".[49][51] Large signs, saying among other things, "The whole world is watching", "Which side are you on?", and "For a world without white supremacy" were held around the monument to block the view while heavy ropes were tied to it.[49]

Between 9:15 and 9:30 p.m., Silent Sam was felled;[52][53][54] the crowd cheered.[49] "People [were] screaming and jumping in disbelief."[3] Holding signs and chanting "stand up, fight back" and "This is what democracy looks like", some protesters stomped on the statue and tried to cover it with dirt. Police, who cordoned off the area around the pedestal, arrested one person who concealed their face in the public protest.[52][53] Some police are reported to have been smiling.[55] Crowds remained around the base, and the Associated Press reported that students were drawn to see it as the news of the toppling spread.[54] Later that night, campus staff loaded the statue, which did not seem to be seriously damaged,[55] onto a flat-bed dump truck and removed it from the site.[56]

Aftermath

The University stated on August 24 that a rally or demonstration at the monument's site, McCorkle Place, and in the town of Chapel Hill, is expected on Saturday, August 25. The announcement added that "some students and others in our community are receiving threats as a result of Monday's events".[57] On Saturday, about two dozen Silent Sam supporters faced about 200 supporters of the removal. Seven arrests were made, for assault, resisting arrest, and inciting a public disturbance.[58]

Also on Saturday, in nearby Durham, "activists will gather for a daylong conference, 'How to Topple a Statue, How to Tear Down a Wall'...to mark the one-year anniversary of the destruction of a Confederate statue there."[59] The group Defend Durham was planning a separate march against white supremacy in Durham at 6:30 p.m. Saturday.[60]

University response

UNC issued a statement on Twitter which read, "Last night's actions were unlawful and dangerous, and we are very fortunate the no one was injured. The police are investigating the vandalism and assessing the full extent of the damage".[51] The chair of the UNC board of governors, Harry Smith, said on August 22 that the board would "hire an outside firm to look into university and police actions at the protest where Silent Sam was toppled", adding that Chancellor Folt had not herself ordered police to take a "hands-off" approach.[55]

Silent Sam is being kept in an undisclosed location for safety concerns.[12] The chancellor has not revealed whether the statue will be restored in McCorkle Place.[46]

Legal

On August 24, it was reported that the Chapel Hill Police Department has filed warrants against three people for "misdemeanor riot and misdemeanor defacing of a public monument". The names of the three individuals, who have not been arrested, have not been released. The Police stated they are not affiliated with the university.[61]

Reactions

Critics of the toppling

- State Representative Bob Steinburg: "It is absolutely inexcusable and those responsible, including security who stood by and let it happen, need to be prosecuted, no excuses!! ... Whoever was on that security detail that allowed this to take place and are seen in this video and can be identified ... need to lose their jobs."[55]

- State Representative Larry Pittman: "Chaos will be the result if nothing is done.... If we don’t stand up and put a stop to this mob rule, it could lead to an actual civil war". He mentioned punishing the University through funding cuts.[62]

- Former Republican State Senator Thom Goolsby, a member of the Board of Governors: "NC State law is CLEAR. Silent Sam MUST be reinstalled."[55]

- A joint statement from UNC Board of Governors Chairman Harry Smith and UNC President Margaret Spellings: "The actions last evening were unacceptable, dangerous, and incomprehensible. We are a nation of laws — and mob rule and the intentional destruction of public property will not be tolerated."[63]

- Senate leader Phil Berger: "Many of the wounds of racial injustice that still exist in our state and country were created by violent mobs and I can say with certainty that violent mobs won't heal those wounds. Only a civil society that adheres to the rule of law can heal these wounds and politicians – from the Governor down to the local District Attorney – must start that process by ending the deceitful mischaracterization of violent riots as 'rallies' and reestablishing the rule of law in each of our state's cities and counties."[63]

- House Speaker Tim Moore: "There is no place for the destruction of property on our college campuses or in any North Carolina community; the perpetrators should be arrested and prosecuted by public safety officials to make clear that mob rule and acts of violence will not be tolerated in our state."[63]

- Statement from Governor Roy Cooper's office: "Governor Cooper has been in contact with local law enforcement and UNC officials regarding tonight's rally and appreciates their efforts to keep people safe. The Governor understands that many people are frustrated by the pace of change and he shares their frustration, but violent destruction of public property has no place in our communities."[64]

- Former governor Pat McCrory, in an August 21 interview, labeled the Monday night protest as mob rule and questioned whether people will begin to call for the destruction of the Washington Monument or Jefferson Memorial, due to George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owning slaves. "Do you think these left-wing anarchists are going to end with Silent Sam?" McCrory said. At another stage in the interview, he compared the actions of the protesters to that of the Nazis who tore down statues and burned books.[65]

Supporters of the toppling

- The Editorial Board of the Charlotte Observer, North Carolina's largest newspaper, saw the toppling of the statue as an act of civil disobedience, "a tradition that goes back at least to Henry David Thoreau, who famously argued that it is the citizen's duty not to acquiesce and allow the government to perpetrate injustice." The toppling of the statue is compared to Rosa Parks, who broke the law by refusing to give up her bus seat, the Greensboro four, and the Boston Tea Party. The Observer says the action was not "mob rule": "Mob rule was what happened at Little Rock Central High School in 1957 when nine black students, even armed with a U.S. Supreme Court ruling, were turned back by an angry and violent white mob."[63]

- Editorial Board of the Winston-Salem Journal: "Silent Sam had to go.... Their cause was just, if not their methods. And it is easy to understand their mounting frustration and anger.... Blame 'mob rule' if you will. But it was poor leadership in Chapel Hill and Raleigh that ultimately led to Monday night."[66]

- Editorial Board of the Washington Post: "It's not a surprise that citizens would take matters into their own hands when arbitrary curbs had been placed on local democracy."[67]

- The UNC undergraduate student government executive branch posted a letter to all students, saying "the African-American activists had 'courage and resilience' and had 'corrected a moral and historical wrong that needed to be righted if we were ever to move forward as a university.'"[68]

- In an OpEd in the New York Times, scholars of slavery Ethan J. Kytle and Blain Roberts, authors of Denmark Vesey's Garden. Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy (2018),[69] professors of history at California State University, Fresno, with Ph.D.s in history from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill: "We once believed that Confederate statues should be left up but also placed in historical context.... Over time, however, we lost our enthusiasm for this approach.... The white supremacist intent of these monuments, in other words, is not a relic of the past.... The prominence of the memorials shows how white Southerners etched racism into the earth with impunity." Their recommendation: leaving the "empty pedestal — shorn all original images and inscriptions — eliminates the offending tribute while still preserving a record of what these communities did and where they did it.... The most effective way to commemorate the rise and fall of white supremacist monument-building is to preserve unoccupied pedestals as the ruins that they are — broken tributes to a morally bankrupt cause."[70]

- 42 UNC faculty members signed a letter published in The News & Observer on August 23 claiming UNC administration "dodged" the Silent Sam issue, leading to "not the most desirable" situation but one that had to come nonetheless. "The time is now for the university administration to show leadership, not bureaucratic obfuscation," the letter reads. "Show us that you and the university do indeed stand for Lux et Libertas, not sustaining and enforcing the symbols of human cruelty."[71] The letter quoted John F. Kennedy: "Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable."[46][72]

- 29 faculty members in the Department of History: "Civil disobedience, particularly among students, has a long and storied history in the United States, especially in the American South. The hyperbolic characterization of Silent Sam's toppling as 'lawlessness' and 'mob action' by Chancellor Folt and UNC System leaders demonstrates a purposeful, obdurate disregard for historical and social context."[71]

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, Stephenson Distinguished Professor of American Civil War Studies, University of North Carolina: "I understand that many people want to honor the sacrifices and efforts of their ancestors, but Silent Sam represented the worst aspects and deeds of those ancestors.... The University and the state should offer magnanimous terms to those students and allow them to return to school unpunished."[73]

- U.S. Representative David Price: "It should not have taken an act of civil disobedience to remove this monument to hate. We should not condone actions that threaten public health or safety but neither should politicians in Raleigh prevent local communities from taking action through peaceful means."[71]

- Karen Cox, professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the author of Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (2003): "People seem to be at their wit's end. When people feel they're not being heard, when people don't have a place at the table, then this is the result."[3]

- Barbara Rimer, Dean of the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in a public letter, "suggested a monument to a person who promoted peace, equity or prevention, instead of a return to Silent Sam."[74] "An ever-potent symbol of a past we said we aimed to transcend, the statue sent a powerful, contradictory message. In its silence, it spoke loudly. It's no wonder that, as other states sought to move beyond the past by removing statues, our inability to do so caused wounds to fester until the pain became unbearable. It is not surprising that it happened Monday night. It is only surprising that it did not happen sooner."[75]

- The University of North Carolina's Center for the Study of the American South: "UNC's leadership refuses to recognize that their own inaction put our community in danger. We acknowledge the constraints they face but we urge them to stand on the right side of history and join us in rejecting simplistic interpretations of last night's actions as vandalism. Silent Sam was violence. Protestors who removed it sought to reorient our future toward non-violence."[71]

- In a joint statement, State Senator Valerie Foushee, Representative Verla Insko, and Representative Graig Meyer said the removal of UNC's Confederate statue was long overdue. "It was past time for Silent Sam to be moved from a place of honor on the campus of the University of the People. It is unfortunate that state legislators chose not to hear and pass the bill we filed earlier this year to move the monument to an indoor site where it would stand as a reminder of the bitter racial struggle that continues to burden our country.[65]

Notes

- ^ $7,500 in 1913 had roughly the same purchasing power as $193,500 in 2018.[21]

- ^ a b The inscriptions are in all capital letters but are rendered here in sentence case for ease of reading.

- ^ "Duty is the sublimest word in the English language" is a quote from a letter once believed to have been written by Robert E. Lee, but revealed in 1914 to have been a forgery.[28]

References

- ^ "The Civil War Years". A Virtual Museum of University History. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Killgrove, Kristina (August 22, 2018). "Scholars Explain The Racist History Of UNC's Silent Sam Statue". Forbes.

- ^ a b c d e f g Farzan, Antonia Noori (August 21, 2018). "'Silent Sam': A racist Jim Crow-era speech inspired UNC students to topple a Confederate monument on campus". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ https://patch.com/north-carolina/charlotte/silent-sam-confederate-statue-be-reinstalled-unc-official

- ^ https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/e1994bf342e4786f24b9ba5df3818e0a.pdf

- ^ https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/225998

- ^ https://dc.lib.unc.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/04ddd/id/226008

- ^ https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/files/original/3333889eb89e79aabbeb85298a8960db.pdf

- ^ "Monument to University's Soldier Sons Unveiled at Chapel Hill," Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC) June 3, 1913 (GenealogyBank) [1]

- ^ https://www.newsobserver.com/living/liv-columns-blogs/past-times/article22788855.html

- ^ a b "'Silent Sam' torn down during protests at UNC". WNCN. August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Pulliam, Tim (August 23, 2018). "Activist calls Silent Sam protesters thugs". WTVD. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Jacobs, Julia (August 24, 2018). "3 Are Charged in Toppling of 'Silent Sam' Statue". New York Times.

- ^ Jacobs, Julia; Blinder, Alan (August 31, 2018). "University of North Carolina Chancellor Explores New Spot for 'Silent Sam'". New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e United Daughters of the Confederacy, North Carolina Division (1910). Minutes of the 14th annual convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy: North Carolina Division. Minutes of the ... annual convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy: [serial] North Carolina Division. Newton, North Carolina: Capital Printing Co. p. 66 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "In Memorial to Carolina's War Dead". Carolina Alumni Review. UNC General Alumni Association. April 25, 2007.

- ^ "Interactive Tour: Confederate Monument". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Nursery of Patriotism: the University at War, 1861-1945—Civil War". UNC University Library Exhibits. University Archives at UNC Chapel Hill. November 13, 2007.

- ^ United Daughters of the Confederacy, North Carolina Division (1906). Minutes of the 11th annual convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy: North Carolina Division. Minutes of the ... annual convention of the United Daughters of the Confederacy: [serial] North Carolina Division. Newton, North Carolina: Enterprise Print. p. 71 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e "A guide to resources about UNC's Confederate monument: Timeline". UNC University Library Exhibits. University Archives at UNC Chapel Hill. 2016.

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- ^ a b c Gutierrez, Michael Keenan (July 7, 2015). "UNC's Silent Sam and Honoring the Confederacy". We're History. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "A guide to resources about UNC's Confederate monument: Archival Resources". UNC University Library Exhibits. University Archives at UNC Chapel Hill. 2016.

- ^ "Silent Sam (Civil War Monument)". The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Virtual Tour. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Carola, Chris (April 18, 2015). "Civil War 'Silent Sentinels' still on guard in North, South". Associated Press.

- ^ "Confederate Monument (a.k.a. Silent Sam)". The Carolina Story: A Virtual Museum of University History. Archived from the original on February 2, 2016. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Confederate Monument, UNC (Chapel Hill)". Documenting the American South: Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina. University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- ^ Heuston, Sean (November 2014). "The Most Famous Thing Robert E. Lee Never Said: Duty, Forgery and Cultural Amnesia". Journal of American Studies. 14 (4). doi:10.1017/S0021875814001315.

- ^ Program for the dedication of the Confederate monument, 1913, UNC Libraries, retrieved August 23, 2018

- ^ Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC) June 3, 1913, page 2, col. 4 (GenealogyBank) [2] : accessed 28 August 2018

- ^ Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, NC) June 3, 1913, page 2, col. 3 (GenealogyBank) [3] : accessed 28 August 2018

- ^ a b c Brundage, W. Fitzhugh (August 18, 2017). "I've studied the history of Confederate memorials. Here's what to do about them". Vox. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Domby, Adam (January 20, 2011). "Why Silent Sam was built: A historian's perspective". Daily Tar Heel.

- ^ a b c Warren-Hicks, Colin (August 23, 2017). "A Long Look at the Controversial Life of 'Silent Sam'". The News & Observer.

- ^ Jennings, Louise (April 9, 1968). "Silent Sam's Dignity Restored". Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ "Confederate Monument". UNC The Graduate School. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Mazza, Ed (July 6, 2015). "'Silent Sam' Confederate Statue At UNC Vandalized". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Lamm, Stephanie (July 9, 2015). "Narratives about Silent Sam collide". The Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ An act to ensure respectful treatment of the American flag and the North Carolina flag by state agencies and other political subdivisions of the state; to establish the Division of Veterans Affairs as the clearinghouse for the disposal of worn, tattered, and damaged flags; to provide for the protection of monuments and memorials commemorating events, persons, and military service in North Carolina history; and to transfer custody of certain historic documents in the possession of the Office of the Secretary of State to the Department of Cultural Resources and to facilitate public opportunity to view these documents (PDF) (SL 2015-170). 23 July 2015.

- ^ Drew, Jonathan (August 23, 2017). "Hundreds protest on UNC campus against Confederate statue". The Associated Press. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Strong, Ted (August 25, 2017). "Top lawmaker says no plans to change NC law protecting Confederate monuments". WNCN. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Chason, Rachel (August 22, 2017). "After Duke incident, rival UNC considers whether to remove Confederate statue". Washington Post. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Stancill, Jane (August 21, 2017). "Cooper tells UNC leaders they can remove Silent Sam if there's 'imminent threat'". News & Observer.

- ^ a b c Stancill, Jane; Carter, Andrew (July 12, 2018). "UNC details security costs near Silent Sam for the last year". News and Observer.

- ^ Moore, Jeff (August 22, 2017). "Gov. Cooper gives UNC green light to remove 'Silent Sam', UNC holds off, citing 2015 law". North State Journal.

- ^ a b c d Stancill, Jane (August 23, 2018). "UNC will 'do everything in our power' to ensure safety, chancellor says". The News & Observer. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Effron, Seth (August 29, 2017). "AG Stein wants Confederate monuments down or moved; awaits request for advisory opinion on law". WRAL-TV. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ Drew, Jonathan (2017-08-22). "Hundreds protest on UNC campus against Confederate statue". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-24. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Jane Stancill (August 20, 2018). "Protesters topple Silent Sam Confederate statue at UNC". Retrieved August 22, 2018.

- ^ Blinder, Alan (August 21, 2018). "Protesters Down Confederate Monument 'Silent Sam' at University of North Carolina". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ a b "US students topple Confederate monument". BBC News. 2018-08-21. Retrieved 2018-08-21.

- ^ a b "'Silent Sam' is down: Protesters topple Confederate statue on UNC campus". WRAL-TV. August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Chapin, Josh (August 20, 2018). "Protesters knock down Silent Sam statue, which had stood on UNC campus since 1913". WTVD. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ a b Drew, Jonathan (August 20, 2018). "Confederate Statue on UNC Campus Toppled by Protesters". The Associated Press. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b c d e Stancill, Jane; Bonner, Lynn; Specht, Paul A. (August 22, 2018). "Police response to Silent Sam protest will be reviewed, UNC board chairman says". News & Observer.

- ^ "Protesters topple Silent Sam Confederate statue at UNC". 2018-08-20.

- ^ University Communications (August 24, 2018). "Message from Carolina on possible rally". Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Joe; Grubb, Tammy; Stancill, Jane (August 25, 2018). "Protesters clash at UNC-Chapel Hill, less than a week after Silent Sam was toppled". Herald-Sun.

- ^ Toth, Casey (August 25, 2018). "Anniversary conference of Durham statue toppling coincides with protest of Silent Sam toppling". Herald-Sun.

- ^ Schultz, Mark; Molina, Camila (August 24, 2018). "UNC-Chapel Hill planning for Confederate statue rally Saturday, tells public stay away". Durham Herald-Sun.

- ^ "UNC-Chapel Hill police charge 3 people in connection with the Silent Sam toppling". WTVD. August 24, 2018.

- ^ Specht, Paul A. (August 23, 2018). "GOP lawmaker fears 'civil war' after Silent Sam toppled". Herald-Sun.

- ^ a b c d Editorial Board (August 23, 2018). "Mob rule at Silent Sam? No, it was something far different". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ "Governor's Office Statement on Silent Sam". North Carolina Office of the Governor. August 20, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Smoot, Ryan (August 22, 2018). "Local, state leaders react to Silent Sam's removal". Daily Tar Heel.

- ^ Editorial Board (August 21, 2018). "Our view: 'Silent Sam' had to go". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ^ Washington Post Editorial Board (August 24, 2018). "North Carolina refused to act on Confederate statues. So protesters did". Washington Post.

- ^ Stancill, Jane; Bonner, Lynn (August 21, 2018). "UNC system officials and state leaders on Silent Sam: 'Mob rule' won't be tolerated". News & Observer.

- ^ Kytle, Ethan J.; Roberts, Blain (2018). of Denmark Vesey's Garden. Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy. The New Press. ISBN 1620973650.}

- ^ Kytle, Ethan J.; Roberts, Blain (August 22, 2018). "Broken Tributes to a Morally Bankrupt Cause". New York Times.

- ^ a b c d McClennan, Hannah; Weber, Jared; Ward, Myah (August 23, 2018). "Chancellor Folt holds Silent Sam press conference, BOG members speak out". Daily Tar Heel.

- ^ "UNC faculty: Where is leadership on Silent Sam issue?". News & Observer. August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Glatthaar, Joseph T. (August 26, 2018). "Silent Sam from a historian's perspective". Daily Tar Heel.

- ^ Stancill, Jane; Carter, Andrew (August 25, 2018). "The unfinished story of Silent Sam, from 'Soldier Boy' to fallen symbol of a painful past". Charlotte Observer.

- ^ Rimer, Barbara K. (August 22, 2018). "Toppling of the Silent Sam statue". Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

External links

- A guide to resources about UNC's Confederate monument, an online collection of primary documents about Silent Sam hosted by the UNC archives and libraries

- Transcription of Julian Carr's speech at the dedication of Silent Sam

- 1913 establishments in North Carolina

- 1913 sculptures

- Bronze sculptures in North Carolina

- Confederate States of America monuments and memorials in North Carolina

- Removed Confederate States of America monuments and memorials

- Sculptures of men in North Carolina

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill landmarks

- United Daughters of the Confederacy

- Vandalized works of art in North Carolina