Stanley Kubrick filmography: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 1013461271 by Trappist the monk (talk) This was intentional... |

move per talk page discussion |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Stanley Kubrick]] (1928–1999)<ref>{{cite news|last=Holden|first=Stephen|date=March 8, 1999|title=Stanley Kubrick, Film Director With a Bleak Vision, Dies at 70|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/08/movies/stanley-kubrick-film-director-with-a-bleak-vision-dies-at-70.html|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 4, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210104140207/https://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/08/movies/stanley-kubrick-film-director-with-a-bleak-vision-dies-at-70.html|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref> directed thirteen [[feature film]]s and three short [[documentaries]] over the course of his career. His work as a director, spanning diverse genres,<ref name="obsess"/> is [[Influence of Stanley Kubrick|widely regarded as influential]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/a-fifty-year-odyssey-how-stanley-kubrick-changed-cinema|title=A Fifty-Year Odyssey: How Stanley Kubrick Changed Cinema|last=Townend|first=Joe|date=July 20, 2018|website=Sotheby's|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=September 27, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200927205339/https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/a-fifty-year-odyssey-how-stanley-kubrick-changed-cinema|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1704-Fall-2017/Stanley-Kubrick-Influence.aspx|title=Kubrick's Outsized Influence|last=Koehler|first=Robert|date=Fall 2017|work=DGA Quaterly|publisher=Directors Guild Of America|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=January 8, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180108233516/https://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1704-Fall-2017/Stanley-Kubrick-Influence.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Chilton|first=Louis|date=September 29, 2019|title=Stanley Kubrick's 10 best films – ranked: From A Clockwork Orange to The Shining|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/stanley-kubrick-best-films-ranked-clockwork-orange-shining-2001-lolita-a8810811.html|work=The Independent|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=November 20, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201120152438/https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/stanley-kubrick-best-films-ranked-clockwork-orange-shining-2001-lolita-a8810811.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

[[Stanley Kubrick]] (1928–1999)<ref>{{cite news|last=Holden|first=Stephen|date=March 8, 1999|title=Stanley Kubrick, Film Director With a Bleak Vision, Dies at 70|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/08/movies/stanley-kubrick-film-director-with-a-bleak-vision-dies-at-70.html|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 4, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210104140207/https://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/08/movies/stanley-kubrick-film-director-with-a-bleak-vision-dies-at-70.html|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref> directed thirteen [[feature film]]s and three short [[documentaries]] over the course of his career. His work as a director, spanning diverse genres,<ref name="obsess"/> is [[Influence of Stanley Kubrick|widely regarded as influential]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/a-fifty-year-odyssey-how-stanley-kubrick-changed-cinema|title=A Fifty-Year Odyssey: How Stanley Kubrick Changed Cinema|last=Townend|first=Joe|date=July 20, 2018|website=Sotheby's|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=September 27, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200927205339/https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/a-fifty-year-odyssey-how-stanley-kubrick-changed-cinema|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1704-Fall-2017/Stanley-Kubrick-Influence.aspx|title=Kubrick's Outsized Influence|last=Koehler|first=Robert|date=Fall 2017|work=DGA Quaterly|publisher=Directors Guild Of America|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=January 8, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180108233516/https://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/All-Articles/1704-Fall-2017/Stanley-Kubrick-Influence.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Chilton|first=Louis|date=September 29, 2019|title=Stanley Kubrick's 10 best films – ranked: From A Clockwork Orange to The Shining|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/stanley-kubrick-best-films-ranked-clockwork-orange-shining-2001-lolita-a8810811.html|work=The Independent|access-date=January 10, 2021|archive-date=November 20, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201120152438/https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/features/stanley-kubrick-best-films-ranked-clockwork-orange-shining-2001-lolita-a8810811.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Kubrick made his directorial debut in 1951 with the documentary short ''[[Day of the Fight]]'', followed by ''[[Flying Padre]]'' later that year. In 1953, he directed his first feature film, ''[[Fear and Desire]]''.<ref>{{cite news|last=Erickson|first=Steve|date=October 24, 2012|title=Stanley Kubrick's First Film Isn't Nearly as Bad as He Thought It Was|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/10/stanley-kubricks-first-film-isnt-nearly-as-bad-as-he-thought-it-was/264068/|work=The Atlantic|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 31, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180131200813/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/10/stanley-kubricks-first-film-isnt-nearly-as-bad-as-he-thought-it-was/264068/|url-status=live}}</ref> The [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] allegory's themes reappeared in his later films.<ref name="guardian"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Burgess|first1=Jackson|date=Autumn 1964|title=The "Anti-Militarism" of Stanley Kubrick|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1210143?seq=1|journal=Film Quarterly|publisher=University of California Press|volume=18|issue=1|pages=4-11|doi=10.2307/1210143|access-date=January 22, 2021|url-access=subscription}}</ref> His next works were the [[film noir]] pictures ''[[Killer's Kiss]]'' (1955) and ''[[The Killing (film)|The Killing]]'' (1956).<ref name="kebert">{{cite web|url=https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/22832/killers-kiss/#overview|title=Killer's Kiss|publisher=Turner Classic Movies|access-date=January 18, 2021|archive-date=October 28, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028184955/https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/22832/killers-kiss/#overview|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="killing"/> Critic [[Roger Ebert]] praised ''The Killing'' and retrospectively called it Kubrick's "first mature feature".<ref name="kebert"/> Kubrick then directed two [[Hollywood]] films starring [[Kirk Douglas]]: ''[[Paths of Glory]]'' (1957) and ''[[Spartacus (film)|Spartacus]]'' (1960).<ref>{{cite news|last=Truit|first=Brian|date=February 5, 2020|title=Five essential Kirk Douglas movies, from 'Paths of Glory' to (obviously) 'Spartacus'|url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2020/02/05/kirk-douglas-celebrating-spartacus-and-other-essential-movie-roles/4674422002/|work=USA Today|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=February 10, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200210140532/https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2020/02/05/kirk-douglas-celebrating-spartacus-and-other-essential-movie-roles/4674422002/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Alberge|first=Dalya|date=November 9, 2020|title=Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas wanted Doctor Zhivago movie rights|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/nov/09/stanley-kubrick-kirk-douglas-wanted-doctor-zhivago-movie-rights|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 22, 2021|archive-date=January 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210117143422/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/nov/09/stanley-kubrick-kirk-douglas-wanted-doctor-zhivago-movie-rights|url-status=live}}</ref> The latter won the [[Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.goldenglobes.com/film/spartacus|title=Spartacus| |

Kubrick made his directorial debut in 1951 with the documentary short ''[[Day of the Fight]]'', followed by ''[[Flying Padre]]'' later that year. In 1953, he directed his first feature film, ''[[Fear and Desire]]''.<ref>{{cite news|last=Erickson|first=Steve|date=October 24, 2012|title=Stanley Kubrick's First Film Isn't Nearly as Bad as He Thought It Was|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/10/stanley-kubricks-first-film-isnt-nearly-as-bad-as-he-thought-it-was/264068/|work=The Atlantic|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 31, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180131200813/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/10/stanley-kubricks-first-film-isnt-nearly-as-bad-as-he-thought-it-was/264068/|url-status=live}}</ref> The [[Anti-war movement|anti-war]] allegory's themes reappeared in his later films.<ref name="guardian"/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Burgess|first1=Jackson|date=Autumn 1964|title=The "Anti-Militarism" of Stanley Kubrick|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1210143?seq=1|journal=Film Quarterly|publisher=University of California Press|volume=18|issue=1|pages=4-11|doi=10.2307/1210143|access-date=January 22, 2021|url-access=subscription}}</ref> His next works were the [[film noir]] pictures ''[[Killer's Kiss]]'' (1955) and ''[[The Killing (film)|The Killing]]'' (1956).<ref name="kebert">{{cite web|url=https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/22832/killers-kiss/#overview|title=Killer's Kiss|publisher=Turner Classic Movies|access-date=January 18, 2021|archive-date=October 28, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028184955/https://www.tcm.com/tcmdb/title/22832/killers-kiss/#overview|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="killing"/> Critic [[Roger Ebert]] praised ''The Killing'' and retrospectively called it Kubrick's "first mature feature".<ref name="kebert"/> Kubrick then directed two [[Hollywood]] films starring [[Kirk Douglas]]: ''[[Paths of Glory]]'' (1957) and ''[[Spartacus (film)|Spartacus]]'' (1960).<ref>{{cite news|last=Truit|first=Brian|date=February 5, 2020|title=Five essential Kirk Douglas movies, from 'Paths of Glory' to (obviously) 'Spartacus'|url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2020/02/05/kirk-douglas-celebrating-spartacus-and-other-essential-movie-roles/4674422002/|work=USA Today|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=February 10, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200210140532/https://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/movies/2020/02/05/kirk-douglas-celebrating-spartacus-and-other-essential-movie-roles/4674422002/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Alberge|first=Dalya|date=November 9, 2020|title=Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas wanted Doctor Zhivago movie rights|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/nov/09/stanley-kubrick-kirk-douglas-wanted-doctor-zhivago-movie-rights|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 22, 2021|archive-date=January 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210117143422/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/nov/09/stanley-kubrick-kirk-douglas-wanted-doctor-zhivago-movie-rights|url-status=live}}</ref> The latter won the [[Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.goldenglobes.com/film/spartacus|title=Spartacus|publisher=Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=March 23, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190323072331/https://www.goldenglobes.com/film/spartacus|url-status=live}}</ref> His next film was ''[[Lolita (1962 film)|Lolita]]'' (1962), an adaptation of [[Vladimir Nabokov]]'s [[Lolita|novel of the same name]].<ref>{{cite news|last=Colapinto|first=John|date=January 2, 2015|title=Nabokov and the Movies|url=https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/adapting-nabokov|work=The New Yorker|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=November 28, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201128102815/https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/adapting-nabokov|url-status=live|url-access=subscription}}</ref> It was nominated for the [[Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1963|title=The 35th Academy Awards|publisher=Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences|access-date=February 27, 2021}}</ref> His 1964 film, the [[Cold War]] satire ''[[Dr. Strangelove]]'' featuring [[Peter Sellers]] and [[George C. Scott]],<ref>{{cite news|last=Ebert|first=Roger|date=July 11, 1999|title=Dr. Strangelove|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-dr-strangelove-1964|publisher=RogerEbert.com|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=December 7, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201207212925/https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-dr-strangelove-1964|url-status=live}}</ref> received the [[BAFTA Award for Best Film]].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://awards.bafta.org/award/1965/film/film|title=Film in 1965|publisher=BAFTA|access-date=January 6, 2021|archive-date=September 9, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190909174810/http://awards.bafta.org/award/1965/film/film|url-status=live}}</ref> Along with ''The Killing'', it remains the highest rated film directed by Kubrick according to [[Rotten Tomatoes]]. |

||

In 1968, Kubrick directed the space epic ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (film)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]''. Now widely regarded as among the [[List of films considered the best#Science fiction|most influential films ever made]],<ref>{{cite news|last=Overbye|first=Dennis|title='2001: A Space Odyssey' Is Still the 'Ultimate Trip' – The rerelease of Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece encourages us to reflect again on where we're coming from and where we're going. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/science/2001-a-space-odyssey-kubrick.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180511122838/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/science/2001-a-space-odyssey-kubrick.html|date=May 10, 2018|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 22, 2021|archive-date=May 11, 2018|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref> ''2001'' garnered Kubrick his only personal [[Academy Award]] for his work as a director of special effects.<ref name="special">{{cite news|last=Child|first=Ben|date=September 4, 2014|title=Kubrick 'did not deserve' Oscar for 2001 says FX master Douglas Trumbull|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/sep/04/stanley-kubrick-did-not-deserve-oscar-2001-special-effects-douglas-trumbull|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222537/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/sep/04/stanley-kubrick-did-not-deserve-oscar-2001-special-effects-douglas-trumbull|url-status=live}}</ref> His next project, the dystopian ''[[A Clockwork Orange (film)|A Clockwork Orange]]'' (1971), was an initially [[X-rated]] adaptation of [[Anthony Burgess]]' [[A Clockwork Orange (novel)|1962 novella]].<ref>{{cite news|date=August 25, 1972|title='Clockwork Orange' To Get an 'R' Rating|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/25/archives/-clockwork-orange-to-get-an-r-rating.html|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 8, 2021|archive-date=January 9, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210109022009/https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/25/archives/-clockwork-orange-to-get-an-r-rating.html|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name="orange"/><ref>{{cite news|last=McCrum|first=Robert|date=April 13, 2015|title=The 100 best novels: No 82 – A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962)|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/13/100-best-novels-clockwork-orange-anthony-burgess|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 8, 2021|archive-date=August 3, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803094620/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/13/100-best-novels-clockwork-orange-anthony-burgess|url-status=live}}</ref> After reports of crimes inspired by the film's depiction of "ultra-violence", Kubrick had the film withdrawn from distribution in the United Kingdom.<ref name="orange"/> Kubrick then directed the period piece ''[[Barry Lyndon]]'' (1975), in a departure from his two previous futuristic films.<ref>{{cite news|last=Sims|first=David|date=October 26, 2017|title=The Alien Majesty of Kubrick's Barry Lyndon|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/10/the-alien-majesty-of-kubricks-barry-lyndon/543993/|work=The Atlantic|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222549/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/10/the-alien-majesty-of-kubricks-barry-lyndon/543993/|url-status=live}}</ref> It did not perform well commercially and received mixed reviews, but won four Oscars at the [[48th Academy Awards]].<ref>{{cite news|date=April 25, 2019|title=Slow burn: Why the languid Barry Lyndon is Kubrick's masterpiece|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3lWVw91r3xlvZyN10rnhqqj/slow-burn-why-the-languid-barry-lyndon-is-kubrick-s-masterpiece|publisher=BBC|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222509/https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3lWVw91r3xlvZyN10rnhqqj/slow-burn-why-the-languid-barry-lyndon-is-kubrick-s-masterpiece|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1976|title=The 48th Academy Awards|publisher=Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=July 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190701234129/https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1976|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1980, Kubrick adapted a [[The Shining (novel)|Stephen King novel]] into ''[[The Shining (film)|The Shining]]'', starring [[Jack Nicholson]] and [[Shelley Duvall]].<ref name="gq"/> Although Kubrick was nominated for a [[Golden Raspberry Awards]] for Worst Director,<ref>{{cite news|last=Marsh|first=Calum|date=January 13, 2016|title=The man behind the Razzies: 'Brian de Palma had no talent'|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/13/razzies-golden-raspberry-film-awards-brian-de-palma|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=November 8, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108110842/http://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/13/razzies-golden-raspberry-film-awards-brian-de-palma|url-status=live}}</ref> ''The Shining'' is now widely regarded as one of the greatest horror films ever made.<ref name="gq">{{cite news|last=Michel|first=Lincoln|date=October 22, 2018|title=The Shining—Maybe the Scariest Movie of All Time—Is on Netflix|url=https://www.gq.com/story/the-shining-netflix|work=GQ|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=November 9, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109040555/https://www.gq.com/story/the-shining-netflix|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Billson|first=Anne|date=October 22, 2012|title=The Shining: No 5 best horror film of all time|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/oct/22/shining-kubrick-horror|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=June 13, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200613230343/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/oct/22/shining-kubrick-horror|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Greene|first=Andy|date=October 8, 2014|title=Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Horror Movies of All Time|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-lists/readers-poll-the-10-best-horror-movies-of-all-time-155470/the-shining-27714/|work=Rolling Stone|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=June 14, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614032904/https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-lists/readers-poll-the-10-best-horror-movies-of-all-time-155470/the-shining-27714/|url-status=live}}</ref> Seven years later, he released the [[Vietnam War]] film ''[[Full Metal Jacket]]''.<ref name="jacket"/> It remains the highest rated of Kubrick's later films according to Rotten Tomatoes and [[Metacritic]]. In the early 1990s, Kubrick abandoned [[Stanley Kubrick's unrealized projects#Aryan Papers|his plans]] to direct a [[The Holocaust|Holocaust]] film titled ''The Aryan Papers''. He was hesitant to compete with [[Steven Spielberg]]'s ''[[Schindler's List]]'' and had become "profoundly depressed" after working extensively on the project.<ref name="obsess">{{cite news|last=Pulver|first=Andrew|date=April 26, 2019|title=Stanley Kubrick: film's obsessive genius rendered more human|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/apr/26/stanley-kubrick-films-obsessive-genius-rendered-more-human|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 6, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210106203404/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/apr/26/stanley-kubrick-films-obsessive-genius-rendered-more-human|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Brody|first=Richard|date=March 24, 2011|title=Archive Fever: Stanley Kubrick and "The Aryan Papers"|url=https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/archive-fever-stanley-kubrick-and-the-aryan-papers|work=The New Yorker|access-date=January 7, 2021|url-access=subscription}}</ref> His final film, the erotic thriller ''[[Eyes Wide Shut]]'' starring [[Tom Cruise]] and [[Nicole Kidman]], was released posthumously in 1999.<ref>{{cite news|last=Turan|first=Kenneth|date=July 16, 1999|title='Eyes' That See Too Much|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jul-16-ca-56405-story.html|work=The Los Angeles Times|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=April 21, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190421112224/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jul-16-ca-56405-story.html|url-status=live|url-access=subscription}}</ref> An unfinished project that Kubrick referred to as ''Pinocchio'' was completed by Spielberg as ''[[A.I. Artificial Intelligence]]'' (2001).<ref>{{cite news|last=Ebert|first=Roger|date=July 7, 2011|title=He just wanted to become a real boy|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-ai-artificial-intelligence-2001|publisher=RogerEbert.com|access-date=August 14, 2020|archive-date=May 17, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517125658/https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-ai-artificial-intelligence-2001|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|date=March 15, 2000|title=Spielberg will finish Kubrick's artificial intelligence movie|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2000/mar/15/news.stevenspielberg|work=The Guardian|location=London|access-date=August 14, 2020|archive-date=March 23, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190323040944/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2000/mar/15/news.stevenspielberg|url-status=live}}</ref> |

In 1968, Kubrick directed the space epic ''[[2001: A Space Odyssey (film)|2001: A Space Odyssey]]''. Now widely regarded as among the [[List of films considered the best#Science fiction|most influential films ever made]],<ref>{{cite news|last=Overbye|first=Dennis|title='2001: A Space Odyssey' Is Still the 'Ultimate Trip' – The rerelease of Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece encourages us to reflect again on where we're coming from and where we're going. |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/science/2001-a-space-odyssey-kubrick.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180511122838/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/science/2001-a-space-odyssey-kubrick.html|date=May 10, 2018|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 22, 2021|archive-date=May 11, 2018|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref> ''2001'' garnered Kubrick his only personal [[Academy Award]] for his work as a director of special effects.<ref name="special">{{cite news|last=Child|first=Ben|date=September 4, 2014|title=Kubrick 'did not deserve' Oscar for 2001 says FX master Douglas Trumbull|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/sep/04/stanley-kubrick-did-not-deserve-oscar-2001-special-effects-douglas-trumbull|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222537/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/sep/04/stanley-kubrick-did-not-deserve-oscar-2001-special-effects-douglas-trumbull|url-status=live}}</ref> His next project, the dystopian ''[[A Clockwork Orange (film)|A Clockwork Orange]]'' (1971), was an initially [[X-rated]] adaptation of [[Anthony Burgess]]' [[A Clockwork Orange (novel)|1962 novella]].<ref>{{cite news|date=August 25, 1972|title='Clockwork Orange' To Get an 'R' Rating|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/25/archives/-clockwork-orange-to-get-an-r-rating.html|work=The New York Times|access-date=January 8, 2021|archive-date=January 9, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210109022009/https://www.nytimes.com/1972/08/25/archives/-clockwork-orange-to-get-an-r-rating.html|url-status=live|url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name="orange"/><ref>{{cite news|last=McCrum|first=Robert|date=April 13, 2015|title=The 100 best novels: No 82 – A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962)|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/13/100-best-novels-clockwork-orange-anthony-burgess|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 8, 2021|archive-date=August 3, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803094620/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/13/100-best-novels-clockwork-orange-anthony-burgess|url-status=live}}</ref> After reports of crimes inspired by the film's depiction of "ultra-violence", Kubrick had the film withdrawn from distribution in the United Kingdom.<ref name="orange"/> Kubrick then directed the period piece ''[[Barry Lyndon]]'' (1975), in a departure from his two previous futuristic films.<ref>{{cite news|last=Sims|first=David|date=October 26, 2017|title=The Alien Majesty of Kubrick's Barry Lyndon|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/10/the-alien-majesty-of-kubricks-barry-lyndon/543993/|work=The Atlantic|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222549/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/10/the-alien-majesty-of-kubricks-barry-lyndon/543993/|url-status=live}}</ref> It did not perform well commercially and received mixed reviews, but won four Oscars at the [[48th Academy Awards]].<ref>{{cite news|date=April 25, 2019|title=Slow burn: Why the languid Barry Lyndon is Kubrick's masterpiece|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3lWVw91r3xlvZyN10rnhqqj/slow-burn-why-the-languid-barry-lyndon-is-kubrick-s-masterpiece|publisher=BBC|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210107222509/https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3lWVw91r3xlvZyN10rnhqqj/slow-burn-why-the-languid-barry-lyndon-is-kubrick-s-masterpiece|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1976|title=The 48th Academy Awards|publisher=Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=July 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190701234129/https://www.oscars.org/oscars/ceremonies/1976|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1980, Kubrick adapted a [[The Shining (novel)|Stephen King novel]] into ''[[The Shining (film)|The Shining]]'', starring [[Jack Nicholson]] and [[Shelley Duvall]].<ref name="gq"/> Although Kubrick was nominated for a [[Golden Raspberry Awards]] for Worst Director,<ref>{{cite news|last=Marsh|first=Calum|date=January 13, 2016|title=The man behind the Razzies: 'Brian de Palma had no talent'|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/13/razzies-golden-raspberry-film-awards-brian-de-palma|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=November 8, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108110842/http://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jan/13/razzies-golden-raspberry-film-awards-brian-de-palma|url-status=live}}</ref> ''The Shining'' is now widely regarded as one of the greatest horror films ever made.<ref name="gq">{{cite news|last=Michel|first=Lincoln|date=October 22, 2018|title=The Shining—Maybe the Scariest Movie of All Time—Is on Netflix|url=https://www.gq.com/story/the-shining-netflix|work=GQ|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=November 9, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109040555/https://www.gq.com/story/the-shining-netflix|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Billson|first=Anne|date=October 22, 2012|title=The Shining: No 5 best horror film of all time|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/oct/22/shining-kubrick-horror|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=June 13, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200613230343/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2010/oct/22/shining-kubrick-horror|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Greene|first=Andy|date=October 8, 2014|title=Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Horror Movies of All Time|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-lists/readers-poll-the-10-best-horror-movies-of-all-time-155470/the-shining-27714/|work=Rolling Stone|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=June 14, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614032904/https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-lists/readers-poll-the-10-best-horror-movies-of-all-time-155470/the-shining-27714/|url-status=live}}</ref> Seven years later, he released the [[Vietnam War]] film ''[[Full Metal Jacket]]''.<ref name="jacket"/> It remains the highest rated of Kubrick's later films according to Rotten Tomatoes and [[Metacritic]]. In the early 1990s, Kubrick abandoned [[Stanley Kubrick's unrealized projects#Aryan Papers|his plans]] to direct a [[The Holocaust|Holocaust]] film titled ''The Aryan Papers''. He was hesitant to compete with [[Steven Spielberg]]'s ''[[Schindler's List]]'' and had become "profoundly depressed" after working extensively on the project.<ref name="obsess">{{cite news|last=Pulver|first=Andrew|date=April 26, 2019|title=Stanley Kubrick: film's obsessive genius rendered more human|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/apr/26/stanley-kubrick-films-obsessive-genius-rendered-more-human|work=The Guardian|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=January 6, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210106203404/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/apr/26/stanley-kubrick-films-obsessive-genius-rendered-more-human|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last=Brody|first=Richard|date=March 24, 2011|title=Archive Fever: Stanley Kubrick and "The Aryan Papers"|url=https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/archive-fever-stanley-kubrick-and-the-aryan-papers|work=The New Yorker|access-date=January 7, 2021|url-access=subscription}}</ref> His final film, the erotic thriller ''[[Eyes Wide Shut]]'' starring [[Tom Cruise]] and [[Nicole Kidman]], was released posthumously in 1999.<ref>{{cite news|last=Turan|first=Kenneth|date=July 16, 1999|title='Eyes' That See Too Much|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jul-16-ca-56405-story.html|work=The Los Angeles Times|access-date=January 7, 2021|archive-date=April 21, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190421112224/https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-jul-16-ca-56405-story.html|url-status=live|url-access=subscription}}</ref> An unfinished project that Kubrick referred to as ''Pinocchio'' was completed by Spielberg as ''[[A.I. Artificial Intelligence]]'' (2001).<ref>{{cite news|last=Ebert|first=Roger|date=July 7, 2011|title=He just wanted to become a real boy|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-ai-artificial-intelligence-2001|publisher=RogerEbert.com|access-date=August 14, 2020|archive-date=May 17, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517125658/https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-ai-artificial-intelligence-2001|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|date=March 15, 2000|title=Spielberg will finish Kubrick's artificial intelligence movie|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2000/mar/15/news.stevenspielberg|work=The Guardian|location=London|access-date=August 14, 2020|archive-date=March 23, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190323040944/https://www.theguardian.com/film/2000/mar/15/news.stevenspielberg|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 23:17, 21 March 2021

Stanley Kubrick (1928–1999)[1] directed thirteen feature films and three short documentaries over the course of his career. His work as a director, spanning diverse genres,[2] is widely regarded as influential.[3][4][5]

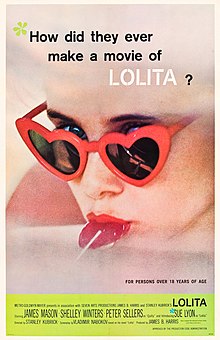

Kubrick made his directorial debut in 1951 with the documentary short Day of the Fight, followed by Flying Padre later that year. In 1953, he directed his first feature film, Fear and Desire.[6] The anti-war allegory's themes reappeared in his later films.[7][8] His next works were the film noir pictures Killer's Kiss (1955) and The Killing (1956).[9][10] Critic Roger Ebert praised The Killing and retrospectively called it Kubrick's "first mature feature".[9] Kubrick then directed two Hollywood films starring Kirk Douglas: Paths of Glory (1957) and Spartacus (1960).[11][12] The latter won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama.[13] His next film was Lolita (1962), an adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov's novel of the same name.[14] It was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[15] His 1964 film, the Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove featuring Peter Sellers and George C. Scott,[16] received the BAFTA Award for Best Film.[17] Along with The Killing, it remains the highest rated film directed by Kubrick according to Rotten Tomatoes.

In 1968, Kubrick directed the space epic 2001: A Space Odyssey. Now widely regarded as among the most influential films ever made,[18] 2001 garnered Kubrick his only personal Academy Award for his work as a director of special effects.[19] His next project, the dystopian A Clockwork Orange (1971), was an initially X-rated adaptation of Anthony Burgess' 1962 novella.[20][21][22] After reports of crimes inspired by the film's depiction of "ultra-violence", Kubrick had the film withdrawn from distribution in the United Kingdom.[21] Kubrick then directed the period piece Barry Lyndon (1975), in a departure from his two previous futuristic films.[23] It did not perform well commercially and received mixed reviews, but won four Oscars at the 48th Academy Awards.[24][25] In 1980, Kubrick adapted a Stephen King novel into The Shining, starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall.[26] Although Kubrick was nominated for a Golden Raspberry Awards for Worst Director,[27] The Shining is now widely regarded as one of the greatest horror films ever made.[26][28][29] Seven years later, he released the Vietnam War film Full Metal Jacket.[30] It remains the highest rated of Kubrick's later films according to Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic. In the early 1990s, Kubrick abandoned his plans to direct a Holocaust film titled The Aryan Papers. He was hesitant to compete with Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List and had become "profoundly depressed" after working extensively on the project.[2][31] His final film, the erotic thriller Eyes Wide Shut starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, was released posthumously in 1999.[32] An unfinished project that Kubrick referred to as Pinocchio was completed by Spielberg as A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001).[33][34]

In 1997, the Venice Film Festival awarded Kubrick the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. That same year, he received a Directors Guild of America Lifetime Achievement Award, then called the D.W. Griffith Award.[35][36] In 1999, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) presented Kubrick with a Britannia Award.[37] After his death, BAFTA renamed the award in his honor: "The Stanley Kubrick Britannia Award for Excellence in Film".[38] He was posthumously awarded a BAFTA Fellowship in 2000.[39]

Films

| Year | Film | Director | Writer | Producer | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Day of the Fight | Yes | Yes | Yes | Documentary short | [40][41] |

| 1951 | Flying Padre | Yes | Yes | Documentary short | [42][43] | |

| 1953 | Fear and Desire | Yes | Yes | [7][44] | ||

| 1953 | The Seafarers | Yes | Yes | Documentary short | [45] | |

| 1955 | Killer's Kiss | Yes | Yes | [46] | ||

| 1956 | The Killing | Yes | Yes | [10] | ||

| 1957 | Paths of Glory | Yes | Yes | [47][48] | ||

| 1960 | Spartacus | Yes | [49] | |||

| 1962 | Lolita | Yes | Uncredited | [50][51] | ||

| 1964 | Dr. Strangelove | Yes | Yes | Yes | [52] | |

| 1968 | 2001: A Space Odyssey | Yes | Yes | Yes | Also editor, director of special effects, and contributed breathing sound-effects | [19][53][54][55] |

| 1971 | A Clockwork Orange | Yes | Yes | Yes | [21][56] | |

| 1975 | Barry Lyndon | Yes | Yes | Yes | [57][58] | |

| 1980 | The Shining | Yes | Yes | Yes | [59] | |

| 1987 | Full Metal Jacket | Yes | Yes | Yes | [30] | |

| 1999 | Eyes Wide Shut | Yes | Yes | Yes | Released posthumously | [60][61] |

Critical response

| Year | Film | Rotten Tomatoes[62] | Metacritic[63] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | Day of the Fight | — | — |

| 1951 | Flying Padre | — | — |

| 1953 | Fear and Desire | 75% (16 reviews) | — |

| 1953 | The Seafarers | — | — |

| 1955 | Killer's Kiss | 86% (21 reviews) | — |

| 1956 | The Killing | 98% (41 reviews) | 91 (15 reviews) |

| 1957 | Paths of Glory | 95% (60 reviews) | 90 (18 reviews) |

| 1960 | Spartacus | 93% (61 reviews) | 87 (17 reviews) |

| 1962 | Lolita | 91% (43 reviews) | 79 (14 reviews) |

| 1964 | Dr. Strangelove | 98% (91 reviews) | 97 (32 reviews) |

| 1968 | 2001: A Space Odyssey | 92% (113 reviews) | 84 (25 reviews) |

| 1971 | A Clockwork Orange | 86% (71 reviews) | 77 (21 reviews) |

| 1975 | Barry Lyndon | 91% (74 reviews) | 89 (21 reviews) |

| 1980 | The Shining | 84% (95 reviews) | 66 (26 reviews) |

| 1987 | Full Metal Jacket | 92% (83 reviews) | 76 (19 reviews) |

| 1999 | Eyes Wide Shut | 75% (158 reviews) | 68 (34 reviews) |

See also

- List of accolades received by Stanley Kubrick

- List of recurring cast members in Stanley Kubrick films

- Stanley Kubrick bibliography

- Stanley Kubrick's unrealized projects

References

- ^ Holden, Stephen (March 8, 1999). "Stanley Kubrick, Film Director With a Bleak Vision, Dies at 70". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Pulver, Andrew (April 26, 2019). "Stanley Kubrick: film's obsessive genius rendered more human". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Townend, Joe (July 20, 2018). "A Fifty-Year Odyssey: How Stanley Kubrick Changed Cinema". Sotheby's. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Koehler, Robert (Fall 2017). "Kubrick's Outsized Influence". DGA Quaterly. Directors Guild Of America. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Chilton, Louis (September 29, 2019). "Stanley Kubrick's 10 best films – ranked: From A Clockwork Orange to The Shining". The Independent. Archived from the original on November 20, 2020. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Erickson, Steve (October 24, 2012). "Stanley Kubrick's First Film Isn't Nearly as Bad as He Thought It Was". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 31, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b French, Phillip (February 2, 2013). "Fear and Desire". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Burgess, Jackson (Autumn 1964). "The "Anti-Militarism" of Stanley Kubrick". Film Quarterly. 18 (1). University of California Press: 4–11. doi:10.2307/1210143. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Killer's Kiss". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (January 9, 2012). "A heist played like a game of chess". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Truit, Brian (February 5, 2020). "Five essential Kirk Douglas movies, from 'Paths of Glory' to (obviously) 'Spartacus'". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (November 9, 2020). "Stanley Kubrick and Kirk Douglas wanted Doctor Zhivago movie rights". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ "Spartacus". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Colapinto, John (January 2, 2015). "Nabokov and the Movies". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "The 35th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved February 27, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 11, 1999). "Dr. Strangelove". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Film in 1965". BAFTA. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (May 10, 2018). "'2001: A Space Odyssey' Is Still the 'Ultimate Trip' – The rerelease of Stanley Kubrick's masterpiece encourages us to reflect again on where we're coming from and where we're going". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Child, Ben (September 4, 2014). "Kubrick 'did not deserve' Oscar for 2001 says FX master Douglas Trumbull". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "'Clockwork Orange' To Get an 'R' Rating". The New York Times. August 25, 1972. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Bradshaw, Peter (April 5, 2019). "A Clockwork Orange review – Kubrick's sensationally scabrous thesis on violence". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (April 13, 2015). "The 100 best novels: No 82 – A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962)". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Sims, David (October 26, 2017). "The Alien Majesty of Kubrick's Barry Lyndon". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Slow burn: Why the languid Barry Lyndon is Kubrick's masterpiece". BBC. April 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "The 48th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Michel, Lincoln (October 22, 2018). "The Shining—Maybe the Scariest Movie of All Time—Is on Netflix". GQ. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Marsh, Calum (January 13, 2016). "The man behind the Razzies: 'Brian de Palma had no talent'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Billson, Anne (October 22, 2012). "The Shining: No 5 best horror film of all time". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Greene, Andy (October 8, 2014). "Readers' Poll: The 10 Best Horror Movies of All Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Wise, Damon (August 1, 2017). "How we made Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Brody, Richard (March 24, 2011). "Archive Fever: Stanley Kubrick and "The Aryan Papers"". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (July 16, 1999). "'Eyes' That See Too Much". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 7, 2011). "He just wanted to become a real boy". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Spielberg will finish Kubrick's artificial intelligence movie". The Guardian. London. March 15, 2000. Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (February 2, 1997). "DGA gives Kubrick D.W. Griffith Award". Variety. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Steven Spielberg to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award, DGA's Highest Honor". Directors Guild of America. Archived from the original on November 28, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Britannia Awards Honorees". BAFTA. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Torres, Vanessa (July 21, 1999). "BAFTA dubs kudo after Kubrick". Variety. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ "Full List of BAFTA Fellows". BAFTA. Archived from the original on August 28, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Far Out Staff (December 28, 2021). "Watch Stanley Kubrick's first-ever short film 'Day of the Fight'". Far Out. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Bernstein, Jeremy (November 5, 1966). "How About a Little Game?". New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Flying Padre". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "The Flying Padre". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 14, 2021.

- ^ "Fear and Desire". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on August 2, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Graser, Mark (August 12, 2013). "Stanley Kubrick's First Color Film, The Seafarers, Streaming on IndieFlix". Variety. Archived from the original on July 3, 2017. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Killer's Kiss". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "Paths of Glory". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Paths of Glory". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (May 3, 1991). "Spartacus". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 14, 1962). "Screen: Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov's Adaptation of His Novel:Sue Lyon and Mason in Leading Roles". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 4, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Trubikhina, Julia (2007). "Struggle for the Narrative: Nabokov and Kubrick's Collaboration on the "Lolita" Screenplay". Ulbandus Review. 10. Columbia University Slavic Department: 149. JSTOR 25748170. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Schlosser, Eric (January 17, 2014). "Almost Everything in "Dr. Strangelove" Was True". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ McKie, Robin (April 15, 2018). "Kubrick's '2001',: the film that haunts our dreams of space". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 27, 1997). "2001: A Space Odyssey". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Whatley, Jack (October 15, 2020). "Stanley Kubrick's secret cameo in 2001: A Space Odyssey". Far Out. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 2, 1972). "A Clockwork Orange". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Gilbey, Ryan (July 14, 2016). "Stanley Kubrick's Barry Lyndon: 'It puts a spell on people'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "Barry Lyndon". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 8, 2006). "Isolated madness". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Nicholson, Amy (July 17, 2014). "Eyes Wide Shut at 15: Inside the Epic, Secretive Film Shoot that Pushed Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to Their Limits". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Eyes Wide Shut". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Stanley Kubrick". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Stanley Kubrick". Metacritic. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

External links

- Stanley Kubrick on IMDb

- Stanley Kubrick at Rotten Tomatoes

- Work and Life of Stanley Kubrick, an educational site