François de La Rocque: Difference between revisions

m Disambiguating links to Major (link changed to Major (rank)) using DisamAssist. |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

== Croix de Feu and February 6, 1934 crisis == |

== Croix de Feu and February 6, 1934 crisis == |

||

La Rocque came from the [[patriotism|patriotic]] and [[social Catholic]] movement created by [[Félicité Robert de Lamennais]] in the late 19th century. He then joined the Croix de Feu in 1929, two years after it had been formed, and took |

La Rocque came from the [[patriotism|patriotic]] and [[social Catholic]] movement created by [[Félicité Robert de Lamennais]] in the late 19th century. He then joined the Croix de Feu in 1929, two years after it had been formed, and took over it in 1930. He quickly transformed the veterans' league; created a paramilitary organisation (''les dispos'', short for ''disponibles'' – availables); and formed a youth organization, the Sons and Daughters of the Croix de Feu (''fils et filles de Croix de Feu''). He also accepted anybody who accepted the league's ideology in the ''Volontaires nationaux'' group (National Volunteers). The [[Great Depression in France|Great Depression]] made La Rocque add to its [[nationalism|nationalist]] ideology a social program of defense of the national economy against foreign competition, protection of the French workforce, lower taxes, fighting speculation and criticisms of the state's influence on the economy. That was overall a vague program, and La Rocque stopped short of giving it the clearly antirepublican and fascist aspect that some National Volunteers demanded of him. |

||

La Rocque concentrated on organizing military parades and was very proud of having taken over the Interior Ministry by two Croix de Feu columns on the eve of the [[February 6, 1934 riots]]. The Croix de Feu took part in the far-right demonstrations in Paris, with two groups, one on the rue de Bourgogne, the other near the ''[[Petit Palais]]''. They were to converge on the [[Palais Bourbon]], the seat of the National Assembly, but La Rocque ordered the disbandment of the demonstration around 8:45 p.m., when the other far-right leagues started rioting on ''[[Place de la Concorde]]'' in front of the Palais Bourbon. Only lieutenant-colonel de Puymaigre, a member of the Croix de Feu and also a Parisian municipal counsellor, attempted to force the police barrage. After the riots, the French far right and sections of the moderate right criticised him for not having attempted to overthrow the [[French Third Republic|Third Republic]]. The journalist [[Alexander Werth]] argued: |

La Rocque concentrated on organizing military parades and was very proud of having taken over the Interior Ministry by two Croix de Feu columns on the eve of the [[February 6, 1934 riots]]. The Croix de Feu took part in the far-right demonstrations in Paris, with two groups, one on the rue de Bourgogne, the other near the ''[[Petit Palais]]''. They were to converge on the [[Palais Bourbon]], the seat of the National Assembly, but La Rocque ordered the disbandment of the demonstration around 8:45 p.m., when the other far-right leagues started rioting on ''[[Place de la Concorde]]'' in front of the Palais Bourbon. Only lieutenant-colonel de Puymaigre, a member of the Croix de Feu and also a Parisian municipal counsellor, attempted to force the police barrage. After the riots, the French far right and sections of the moderate right criticised him for not having attempted to overthrow the [[French Third Republic|Third Republic]]. The journalist [[Alexander Werth]] argued: |

||

Revision as of 14:10, 16 December 2023

François de La Rocque | |

|---|---|

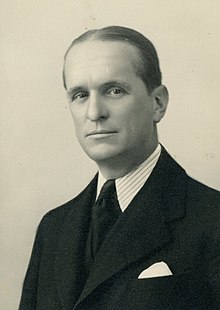

1930s photograph of François de La Rocque | |

| Born | 6 October 1885 |

| Died | 28 April 1946 (aged 60) |

| Alma mater | Saint Cyr Military Academy |

| Occupation(s) | Military man, political activist |

| Title | Colonel |

François de La Rocque (French: [fʁɑ̃swa dəlaʁɔk]; 6 October 1885 – 28 April 1946) was the leader of the French right-wing league the Croix de Feu from 1930 to 1936 before he formed the more moderate nationalist French Social Party (1936–1940), which has been described by several historians, such as René Rémond and Michel Winock, as a precursor of Gaullism.[1][2][3]

Early life

La Roque was born on 6 October 1885 in Lorient, Brittany, the third son of a family from Haute-Auvergne. His parents were General Raymond de La Rocque, commander of the artillery defending the Lorient Naval Base, and Anne Sollier.

He entered Saint Cyr Military Academy in 1905 in a class known as "Promotion la Dernière du Vieux Bahut". He graduated in 1907 and was posted to Algeria and the edge of the Sahara and in 1912 to Lunéville. The next year, he was called to Morocco by General Hubert Lyautey. Despite the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, La Roque remained there until 1916 as officer of native affairs, when he was gravely wounded and repatriated to France. Meanwhile, his older brother Raymond, a major in the army, had been killed in action in 1915. However, La Roque volunteered to fight on the Western Front and was sent to the trenches of the Somme to command a battalion.

After the First World War ended in 1918, he was assigned to the interallied staff of Marshal Ferdinand Foch, but in 1921 he went to Poland with the French Military Mission under General Maxime Weygand. In 1925, he was made chief of the Second Bureau in the Rif War during Marshal Philippe Pétain's campaign against Abd el-Krim in Morocco. La Rocque resigned from the French Army in 1927 with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Croix de Feu and February 6, 1934 crisis

La Rocque came from the patriotic and social Catholic movement created by Félicité Robert de Lamennais in the late 19th century. He then joined the Croix de Feu in 1929, two years after it had been formed, and took over it in 1930. He quickly transformed the veterans' league; created a paramilitary organisation (les dispos, short for disponibles – availables); and formed a youth organization, the Sons and Daughters of the Croix de Feu (fils et filles de Croix de Feu). He also accepted anybody who accepted the league's ideology in the Volontaires nationaux group (National Volunteers). The Great Depression made La Rocque add to its nationalist ideology a social program of defense of the national economy against foreign competition, protection of the French workforce, lower taxes, fighting speculation and criticisms of the state's influence on the economy. That was overall a vague program, and La Rocque stopped short of giving it the clearly antirepublican and fascist aspect that some National Volunteers demanded of him.

La Rocque concentrated on organizing military parades and was very proud of having taken over the Interior Ministry by two Croix de Feu columns on the eve of the February 6, 1934 riots. The Croix de Feu took part in the far-right demonstrations in Paris, with two groups, one on the rue de Bourgogne, the other near the Petit Palais. They were to converge on the Palais Bourbon, the seat of the National Assembly, but La Rocque ordered the disbandment of the demonstration around 8:45 p.m., when the other far-right leagues started rioting on Place de la Concorde in front of the Palais Bourbon. Only lieutenant-colonel de Puymaigre, a member of the Croix de Feu and also a Parisian municipal counsellor, attempted to force the police barrage. After the riots, the French far right and sections of the moderate right criticised him for not having attempted to overthrow the Third Republic. The journalist Alexander Werth argued:

- At that time the Croix de Feu, the Royalists, the Solidarité and the Jeunesses Patriotes had no more than a few thousand active members between them, and that they would have been incapable of a real armed uprising. What they reckoned on was the support of the Paris public as a whole; and the most that they could reasonably have aimed at was the resignation of the Daladier Government. When this happened, on February 7, Colonel de la Rocque announced that 'the first objective had been attained.'[4]

Parti Social Français

In June 1936 the Croix-de-Feu, along with all other French far-right leagues, was dissolved by the Popular Front government, and La Rocque then formed the Parti Social Français or PSF (1936), which lasted until the German invasion of 1940. Until 1940, the PSF took an increasingly-moderate position to become the first French right-wing mass party, with 600,000 to 800,000 members between 1936 and 1940. Its programme was nationalist but not openly fascist. The French historians Pierre Milza and René Rémond consider that the success of the moderate, Christian social and democratic PSF prevented the French middle class from falling into fascism.[5] Milza wrote "Populist and nationalist, the PSF is more anti-parliamentarian than anti-republican". He reserved the term "fascism" for Jacques Doriot's Parti populaire français (PPF), insisting on the latter party's anticommunism as an important trait of the new form of fascism.[6] However, that characterisation of the PSF has been questioned; for example, Robert Soucy has argued that the differences between the PSF and fascist movements in Italy and Germany were more superficial than their similarities and that La Rocque was "a dyed-in-the-wool fascist".[3][2]

Second World War

After the Battle of France of 1940, La Rocque accepted "without restrictions" the terms of the June 1940 Armistice and reorganised the PSF which became the Progrès Social Français (French Social Progress). La Rocque also accepted the "principle of collaboration", upheld by Marshal Philippe Pétain in December 1940. However, at the same time, he was attacked by sectors of the far right, which claimed that he had founded his newspaper with funds from a "Jewish consortium". His attitude remained ambiguous, as he wrote an article in Le Petit Journal of October 5, 1940, concerning "The Jewish Question in Metropolitan France and North Africa" (La question juive en métropole et en Afrique du Nord).[7] H. R. Knickerbocker wrote in 1941 that the Petit Journal with La Rocque as editor "assumed a more courageously anti-German attitude after the armistice than did most other papers published under the control of the Vichy government".[8] On 23 January 1941, La Rocque was made a member of the National Council of Vichy France.[9] La Rocque approved the repeal of the Crémieux decrees, which had given French citizenship to Jews in Algeria, but he did not follow the Vichy regime in its racist radicalization. He also condemned the ultracollaborationist Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism.

La Rocque changed orientation in September 1942 by declaring, "Collaboration was incompatible with Occupation". He entered contact with the Réseau Alibi, which tied to the British Intelligence service. He then formed the Réseau Klan Resistance network with some members of the PSF. La Rocque rejected the laws on the STO, which forced young Frenchmen to work in Germany, and he also threatened to expel any member of the PSF who joined Joseph Darnand's Milice or the LVF.

He was arrested in Clermont-Ferrand on March 9, 1943, by the SIPO-SD German police along with 152 high ranking PSF members in Paris, allegedly because he had been trying to convince Pétain to go to North Africa. He was deported first to Eisenberg Castle, now in the Czech Republic; then to Itter Castle, Austria, where he found former President of the Council Édouard Daladier and Generals Maurice Gamelin and Maxime Weygand. Ill, he was interned in March 1945 in a hospital in Innsbruck and was freed by US soldiers on May 8, 1945. He returned to France on May 9 and was placed under administrative internment, allegedly to keep him away from political negotiations, especially from the Conseil national de la Résistance (CNR), the unified organisation of the resistance. After being released, he was placed under house arrest[by whom?] and died on April 28, 1946.

Political heritage

The Parti Social Français (PSF) of François de La Rocque has been described as the first right-wing mass party in France (1936–1940).[2][10] He advocated:

- a presidential regime to end the instability of the parliamentary regime.

- an economic system founded upon "organised professions" (corporatism).

- social legislation inspired by Social Christianity.

Several historians consider that he paved the way to two leading parties of the post-war "republican Right", the Christian democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP) and the Gaullist Union of Democrats for the Republic.[2][11]

See also

References

- ^ René Rémond, Les Droites en France (first ed. Aubier-Montaigne, 1968)

- ^ a b c d Winock, Michel (April–June 2006). "Revisiting French fascism: La Rocque and the Croix-de-Feu". Vingtième Siècle (90): 3–27. doi:10.3917/ving.090.0003. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Brian (2005). "Introduction: Contextualising the Immunity Thesis" (PDF). In Jenkins, Brian (ed.). France in the Era of Fascism. New York City: Berghahn Books. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1-57181-537-8. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Alexander Werth and D. W. Brogan, The Twilight of France, 1933-1940, (1942) p 16 online

- ^ John Bingham, "Defining French fascism, finding fascists in France" in Canadian Journal of History 29.3 (1994): 525-544.

- ^ Pierre Milza, La France des années 30, Armand Colin, 1988, p.132

- ^ Biography of François de La ROCQUE (in French)

- ^ Knickerbocker, H.R. (1941). Is Tomorrow Hitler's? 200 Questions On the Battle of Mankind. Reynal & Hitchcock. p. 251. ISBN 9781417992775.

- ^ "Journal officiel de la République française. Lois et décrets". Gallica. 1941-01-24. Retrieved 2023-08-13.

- ^ Godet, Antoine (3 March 2014). "Le PSF, un parti de masse à droite" [The PSF, a mass party of the right] (PDF). Histoire@Politique (in French). Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Thomas, Jean=Paul (2012). "Le Parti social français (PSF), obstacle à la radicalisation des droites. Contribution historique à une réflexion sur les droites, la radicalité et les cultures politiques françaises" [The Parti social français (PSF), obstacle to the radicalisation of the right. Historical contribution to a reflection on the right, radicalism and French political cultures]. In Vervaecke, Philippe (ed.). À droite de la droite: Droites radicales en France et en Grande-Bretagne au xxe siècle (in French). Villeneuve-d'Ascq: Presses universitaires du Septentrion. pp. 243–273. doi:10.4000/books.septentrion.16175. ISBN 9782757418536. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

Bibliography

- François de la Rocque, Pour la conférence du désarmement. La Sécurité française, Impr. De Chaix, 1932.

- François de la Rocque, Service public, Grasset, 1934.

- François de la Rocque, Le Mouvement Croix de feu au secours de l'agriculture française, Mouvement Croix de feu, 1935.

- François de la Rocque, Pourquoi j'ai adhéré au Parti social français, Société d'éditions et d'abonnements, Paris, décembre 1936.

- Mouvement social français de Croix-de-Feu, Pourquoi nous sommes devenus Croix de Feu (manifeste), Siège des groupes, Clermont, 1937.

- François de la Rocque, Union, esprit, famille, discours prononcé par La Rocque au Vél'd'hiv, Paris, 28 janvier 1938, Impr. Commerciale, 1938.

- François de la Rocque, Paix ou guerre (discours prononcé au Conseil national du P.S.F., suivi de l'ordre du jour voté au Conseil ; Paris, 22 avril 1939), S.E.D.A., Paris, 1939.

- François de la Rocque, Discours, Parti social français. Ier Congrès national agricole. 17-18 février 1939., SEDA, 1939.

- François de la Rocque, Disciplines d'action, Editions du Petit Journal, Clermont-Ferrand, 1941.

- François de la Rocque, Au service de l'avenir, réflexions en montagne, Société d'édition et d'abonnement, 1949.

- Amis de la Rocque (ALR), Pour mémoire : La Rocque, les Croix de feu et le Parti social français, Association des amis de La Rocque, Paris, 1985.

- Amis de La Rocque (ALR), Bulletin de l'association.

Studies

- Kevin Passmore, From liberalism to fascism : the right in a French province, 1928-1939, Cambridge university press, 1997.

- Jacques Nobécourt, Le Colonel de la Rocque, ou les pièges du nationalisme chrétien, Fayard, Paris, 1996.

- Michel Winock, Le siècle des intellectuels, Seuil, 1999.

External links

Media related to François de La Rocque at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to François de La Rocque at Wikimedia Commons- Biography of François de La ROCQUE (in French)

- Newspaper clippings about François de La Rocque in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1885 births

- 1946 deaths

- Politicians from Lorient

- French Social Party politicians

- Members of the National Council of Vichy France

- Right-wing populism in France

- French Army officers

- École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr alumni

- French people imprisoned abroad

- French military personnel of World War I

- French Resistance members

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- Prisoners and detainees of Germany