Acratocnus: Difference between revisions

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Hemiauchenia (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

== Description == |

== Description == |

||

''Acratocnus ye'' |

''Acratocnus ye'' and ''A. odontrigonus'' have been estimated to weigh approximately {{Convert|15|kg|lb}}, while ''A. antillensis'' is estimated to be somewhat smaller at around {{Convert|10|kg|lb}}.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McDonald |first=H. Gregory |date=2023-06 |title=A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths |url=https://www.mdpi.com/2073-445X/12/6/1192 |journal=Land |language=en |volume=12 |issue=6 |pages=1192 |doi=10.3390/land12061192 |issn=2073-445X}}</ref> All species of ''Acratocnus'' were somewhat larger than living [[tree sloths]], though small in comparison to mainland [[ground sloths]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Gaudin |first=Timothy J. |last2=Scaife |first2=Thomas |date=22 August 2022 |title=Cranial osteology of a juvenile specimen of Acratocnus ye (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Folivora) and its ontogenetic and phylogenetic implications |url=https://anatomypubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ar.25062 |journal=The Anatomical Record |language=en |volume=306 |issue=3 |pages=607–637 |doi=10.1002/ar.25062 |issn=1932-8486}}</ref> The skulls of ''Acratocnus'' are markedly domed along their [[Sagittal crest|sagittal crests]].<ref name="MacPhee20002" /> The skull of ''A. antillensis'' is distinguished from other species within the genus ''Acratocnus'' by its prominent [[Palatine foramen|palatine foramina]] and a short, pointed [[Symphysis|symphyseal]] spout.<ref name="MacPheeEtAl2021">{{cite book |last1=MacPhee |first1=Ross |title=Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives |publisher=CRC Press |year=2021 |isbn=978-1138561733 |display-authors=etal}}</ref><ref name="McAfee2019">{{cite journal |last1=McAfee |first1=Robert K. |last2=Beery |first2=Sophia M. |year=2019 |title=Intraspecific variation of Megalonychid sloths from Hispaniola and the taxonomic implications |journal=Historical Biology |volume=33 |issue=3 |pages=371–386 |doi=10.1080/08912963.2019.1618294}}</ref> The [[skull]] of ''A. simorhynchus'' is distinguish from other species within the genus ''Acratocnus'' by its prominent [[frontal sinuses]], resulting in a foreshortened snout. The species also exhibits a pronounced medio-lateral flare of the rostrum, a short symphyseal spout, and deep mandibular corpus.<ref name="Rega2002">{{cite journal |last1=Rega |first1=Elizabeth |last2=McFarlane |first2=Donald A. |last3=Lundberg |first3=Joyce |last4=Christenson |first4=Keith |year=2002 |title=A new megalonychid sloth from the late Wisconsinan of the Dominican Republic |journal=Caribbean Journal of Science |volume=38 |issue=1–2 |pages=11–19}}</ref><ref name="Gaudin2004">{{cite journal |last1=Gaudin |first1=Timothy |year=2004 |title=Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence |journal=Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society |volume=140 |issue=2 |pages=255–305 |doi=10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x}}</ref> The [[skull]] of ''A. ye'' is distinguished from other species within the genus ''Acractocnus'' by its flattened nose, giving it a "snub nosed" look.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

== Ecology == |

== Ecology == |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

== Extinction == |

== Extinction == |

||

The various species of Carribbean sloth are though to have become extinct following human arrival to the Carribean around 6,000 years ago. |

|||

As with many sloth fossils, these species of sloth have not been radiometrically dated.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://academic.uprm.edu/publications/cjs/Vol35b/35_238-248.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110720101550/http://academic.uprm.edu/publications/cjs/Vol35b/35_238-248.pdf |archive-date=2011-07-20 |journal=Caribbean Journal of Science|volume=35|issue=3–4|pages=238–248|date=1999|title=Late Quaternary Fossil Mammals and Last Occurrence Dates from Caves at Barahona, Puerto Rico|author=Donald A. McFarlane|access-date=29 May 2022}}</ref> It is suggested{{by whom|date=March 2019}} that the Puerto Rican and Hispaniolan ''Acratocnus'' species survived into the late [[Pleistocene]] but disappeared by the mid-[[Holocene]].{{citation needed|date=March 2019}} The related Cuban ground sloth, ''[[Megalocnus]] rodens'', survived until at least c. 6600 [[Before Present|BP]],<ref name="Steadman">{{cite journal | last = Steadman | first = D. W. |author2=Martin, P. S. |author3=MacPhee, R. D. E. |author4=Jull, A. J. T. |author5=McDonald, H. G. |author6=Woods, C. A. |author7=Iturralde-Vinent, M. |author8=Hodgins, G. W. L. | author1link = David Steadman | author2link = Paul Schultz Martin | title = Asynchronous extinction of late Quaternary sloths on continents and islands | journal = [[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA]] | volume = 102 | issue = 33 | pages = 11763–11768 | publisher = [[United States National Academy of Sciences|National Academy of Sciences]] | date = 2005-08-16 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0502777102 | pmid = 16085711 | pmc = 1187974| bibcode = 2005PNAS..10211763S | doi-access = free }}</ref> and the latest survival reported for any of the Antillean sloths is c. 5000 BP, for the [[Hispaniola]]n ''Neocnus comes'',<ref name="Steadman"/> based on [[Accelerator mass spectrometry|AMS]] [[radiocarbon dating]]. The cause(s) of their extinctions may have been climatic changes, or more likely, human hunting by the [[indigenous peoples of the Caribbean]].<ref name="Steadman"/> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 21:00, 9 July 2024

| Acratocnus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Acratocnus ye skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Megalocnidae |

| Genus: | †Acratocnus Anthony 1916 |

| Type species | |

| †Acratocnus odontrigonus Anthony, 1916

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Acratocnus is an extinct genus of Caribbean sloths that were found on Cuba, Hispaniola (today the Dominican Republic and Haiti), and Puerto Rico during the Late Pleistocene and early-mid Holocene.

Taxonomy

The genus was first described by American paleontologist Harold Elmer Anthony in 1916 based on the species A. odontrigonus, which was found in cave deposits in Puerto Rico.[1] Acratocnus antillensis was first described by William Diller Matthew in 1931. The species was identified based on fossil remains found in various locations in Cuba, including the paleontological deposit Las Llanadas, Sancti Spíritus Province.[2][3] Acratocnus ye was first described by Ross D. E. MacPhee, Jennifer L. White, and Charles A. Woods in 2000. The species was identified based on fossil remains found in various locations in Haiti, including the type locality at Trouing Vape`Deron, Plain Formon, Département du Sud.[4] The holotype specimen, UF170533, consists of a skull and mandible.[5] Acratocnus simorhynchus was first described in 2002. The species was identified based on fossil remains found in Cueva del Perezoso, located in Jaragua National Park, Pedernales Province, Dominican Republic.[6] The holotype, catalogued as ALF 7194, includes an unusually well-preserved skull, mandible, and post-cranial elements.[6]

Like all of the Antillean sloths, Acratocnus was formerly thought on the basis of morphological evidence to be a member of the family Megalonychidae, which was also thought to include Choloepus, the two-toed tree sloths. Recent molecular evidence has clarified that Caribbean sloths represent a separate basal branch of the sloth radiation,[7][8] now placed in the family Megalocnidae.[7]

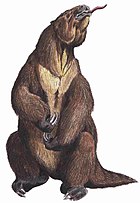

Description

Acratocnus ye and A. odontrigonus have been estimated to weigh approximately 15 kilograms (33 lb), while A. antillensis is estimated to be somewhat smaller at around 10 kilograms (22 lb).[9] All species of Acratocnus were somewhat larger than living tree sloths, though small in comparison to mainland ground sloths.[5] The skulls of Acratocnus are markedly domed along their sagittal crests.[4] The skull of A. antillensis is distinguished from other species within the genus Acratocnus by its prominent palatine foramina and a short, pointed symphyseal spout.[10][11] The skull of A. simorhynchus is distinguish from other species within the genus Acratocnus by its prominent frontal sinuses, resulting in a foreshortened snout. The species also exhibits a pronounced medio-lateral flare of the rostrum, a short symphyseal spout, and deep mandibular corpus.[12][13] The skull of A. ye is distinguished from other species within the genus Acractocnus by its flattened nose, giving it a "snub nosed" look.[5]

Ecology

Species of Acratocnus inhabited forested environments. The various species are though to have been semi-arboreal, having spent some of their time in trees and some on the ground[5], with their hooked claws being used both for climbing and terrestrial foraging.[12]

Extinction

The various species of Carribbean sloth are though to have become extinct following human arrival to the Carribean around 6,000 years ago.

See also

References

- ^ Anthony, H. E. 1918. The indigenous land mammals of Porto Rico, living and extinct. Mem. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. n. ser. 2: 331–435.

- ^ Rodriguez-Silva, Ricardo (2021). "Biogeography of the West Indies: A complex scenario for species radiations". Ecology and Evolution. 11 (14): 9447–9463. doi:10.1002/ece3.7771. PMID 34306640.

- ^ Orihuela, Johanset; Suarez, William; Balseiro, Diego (2020). "Late Holocene land vertebrate fauna from Cueva de los Nesofontes: Stratigraphy, chronology and paleoecology". Historical Biology. 32 (5): 596–607. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1618294.

- ^ a b MacPhee, R. D. E.; White, Jennifer L.; Woods, Charles A. (2000). "New Megalonychid Sloths (Phyllophaga, Xenarthra) from the Quaternary of Hispaniola". American Museum Novitates (3303): 1–32.

- ^ a b c d Gaudin, Timothy J.; Scaife, Thomas (22 August 2022). "Cranial osteology of a juvenile specimen of Acratocnus ye (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Folivora) and its ontogenetic and phylogenetic implications". The Anatomical Record. 306 (3): 607–637. doi:10.1002/ar.25062. ISSN 1932-8486.

- ^ a b Rega, Elizabeth; McFarlane, Donald A.; Lundberg, Joyce; Christenson, Keith (2002). "A new megalonychid sloth from the late Wisconsinan of the Dominican Republic". Caribbean Journal of Science. 38 (1–2): 11–19.

- ^ a b Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3.1121P. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G. C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J. G.; Mead, J. I.; McDonald, H. G.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Billet, G.; Hautier, L.; Poinar, H. N. (2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. Bibcode:2019CBio...29E2031D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. hdl:11336/136908. PMID 31178321.

- ^ McDonald, H. Gregory (2023-06). "A Tale of Two Continents (and a Few Islands): Ecology and Distribution of Late Pleistocene Sloths". Land. 12 (6): 1192. doi:10.3390/land12061192. ISSN 2073-445X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ MacPhee, Ross; et al. (2021). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1138561733.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ McAfee, Robert K.; Beery, Sophia M. (2019). "Intraspecific variation of Megalonychid sloths from Hispaniola and the taxonomic implications". Historical Biology. 33 (3): 371–386. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1618294.

- ^ a b Rega, Elizabeth; McFarlane, Donald A.; Lundberg, Joyce; Christenson, Keith (2002). "A new megalonychid sloth from the late Wisconsinan of the Dominican Republic". Caribbean Journal of Science. 38 (1–2): 11–19.

- ^ Gaudin, Timothy (2004). "Phylogenetic relationships among sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Tardigrada): the craniodental evidence". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 140 (2): 255–305. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00100.x.