Giraffe: Difference between revisions

'Fauna of' -> 'Mammals of' |

m →Necking: Removed link on the word "necking". Just goes to the disambiguation page, and there's no relevant link there. |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

===Necking=== |

===Necking=== |

||

The males often engage in |

The males often engage in necking, which has been described as having various functions. One of these is combat. These battles can be fatal, but are more often less severe. The longer a neck is, and the heavier the head at the end of the neck, the greater force a giraffe will be able to deliver in a blow. It has also been observed that males that are successful in necking have greater access to [[Estrous cycle|estrous]] females, so that the length of the neck may be a product of [[sexual selection]].<ref>Robert E. Simmons and Lue Scheepers: [http://bill.srnr.arizona.edu/classes/182/Giraffe/WinningByANeck.pdf Winning by a neck: Sexual selection in the evolution of giraffe.] ''The American Naturalist'', 148 (1996): pp. 771-786.</ref> |

||

After a necking duel, a giraffe can land a powerful blow with his head occasionally knocking a male opponent to the ground. These fights rarely last more than a few minutes or end in physical harm. |

After a necking duel, a giraffe can land a powerful blow with his head occasionally knocking a male opponent to the ground. These fights rarely last more than a few minutes or end in physical harm. |

||

Revision as of 21:38, 8 August 2007

| Giraffe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Giraffa

|

| Species: | G. camelopardalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Giraffa camelopardalis | |

| |

| Range map | |

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) is an African even-toed ungulate mammal, the tallest of all land-living animal species. Males can be 4.8 to 5.5 metres (16 to 18 feet) tall and weigh up to 1,360 kilograms (3,000 pounds). The record-sized bull was 5.87 m (19.2 feet) tall and weighed approximately 2,000 kg (4,400 lbs.).[2] Females are generally slightly shorter and weigh less than the males do.

The giraffe is related to deer and cattle, but is placed in a separate family, the Giraffidae, consisting only of the giraffe and its closest relative, the okapi. Its range extends from Chad to South Africa.

Taxonomy and naming

The species name camelopardalis (camelopard) is derived from its early Roman name, where it was described as having characteristics of both a camel and a leopard.[3] The English word camelopard first appeared in the 14th century and survived in common usage well into the 19th century. A number of European languages retain it. The Arabic word الزرافة ziraafa or zurapha, meaning "assemblage" (of animals), or just "tall", was used in English from the sixteenth century on, often in the Italianate form giraffa.

Classification

There are nine generally accepted subspecies, differentiated by color and pattern variations and range:

- Reticulated or Somali Giraffe (G.c. reticulata) — large, polygonal liver-colored spots outlined by a network of bright white lines. The blocks may sometimes appear deep red and may also cover the legs. Range: northeastern Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia.

- Angolan or Smoky Giraffe (G.c. angolensis) — large spots and some notches around the edges, extending down the entire lower leg. Range: Angola, Zambia.

- Kordofan Giraffe (G.c. antiquorum) — smaller, more irregular spots that cover the inner legs. Range: western and southwestern Sudan.

- Masai or Kilimanjaro Giraffe (G.c. tippelskirchi) — jagged-edged, vine-leaf shaped spots of dark chocolate on a yellowish background. Range: central and southern Kenya, Tanzania.

- Nubian Giraffe (G.c. camelopardalis) — large, four-sided spots of chestnut brown on an off-white background and no spots on inner sides of the legs or below the hocks. Range: eastern Sudan, northeast Congo.

- Rothschild Giraffe or Baringo Giraffe or Ugandan Giraffe (G.c. rothschildi) — deep brown, blotched or rectangular spots with poorly defined cream lines. Hocks may be spotted. Range: Uganda, north-central Kenya.

- South African Giraffe (G.c. giraffa) — rounded or blotched spots, some with star-like extensions on a light tan background, running down to the hooves. Range: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique.

- Thornicroft or Rhodesian Giraffe (G.c. thornicrofti) — star-shaped or leafy spots extend to the lower leg. Range: eastern Zambia.

- West African or Nigerian Giraffe (G.c. peralta) — numerous pale, yellowish red spots. Range: Niger, Cameroon.

Some scientists regard Kordofan and West African Giraffes as a single subspecies; similarly with Nubian and Rothschild's Giraffes, and with Angolan and South African Giraffes. Further, some scientists regard all populations except the Masai Giraffes as a single subspecies. By contrast, scientists have proposed four other subspecies — Cape Giraffe (G.c. capensis), Lado Giraffe (G.c. cottoni), Congo Giraffe (G.c. congoensis), and Transvaal Giraffe (G.c. wardi) — but none of these is widely accepted.

Description

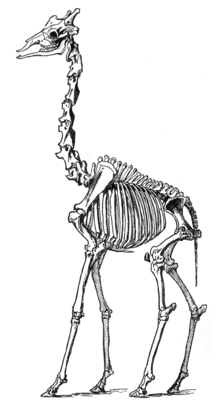

Male giraffes are around 16–18 feet (4.5-5.5 metres) tall at the horn tips, and weigh 1700–4200 lb. (770-1900 kg) Females are one to two feet (30-60 cm) shorter and weigh several hundred pounds less than males. Both sexes have horns, although the horns of a female are smaller. The prominent horns are formed from ossified cartilage and are called ossicones. The appearance of horns is a reliable method of identifying the sex of giraffes, with the females displaying tufts of hair on the top of the horns, whereas males' horns tend to be bald on top - an effect of necking in combat. Males sometimes develop calcium deposits which form bumps on their skull as they age, which can give the appearance of up to three further horns.[4]

Giraffes have spots covering their entire bodies, except their underbellies, with each giraffe having a unique pattern of spots. They have long, prehensile tongues that are impervious to the thorns of the acacia trees that they feed from and are distinctly blue-black to protect from sunburn.[citation needed] Giraffes have long necks, which they use to browse the leaves of trees. They possess seven vertebrae in the neck (the usual number for a mammal). They also have slightly elongated forelegs, about 10% longer than their hind legs.

Modifications to the giraffe's structure have evolved, particularly to the circulatory system. A giraffe's heart, which can weigh up to 10 kg (24 lb) and measure about 2 feet long, has to generate around double the normal blood pressure for an average large mammal in order to maintain blood flow to the brain against gravity. In the upper neck, a complex pressure-regulation system called the rete mirabile prevents excess blood flow to the brain when the giraffe lowers its head to drink. Conversely, the blood vessels in the lower legs are under great pressure (because of the weight of fluid pressing down on them). In other animals such pressure would force the blood out through the capillary walls; giraffes, however, have a very tight sheath of thick skin over their lower limbs which maintains high extravascular pressure in exactly the same way as a pilot's g-suit.

Giraffes have purple or dark blueish tounges. [citation needed]

Some giraffes can lose the bottom part of their tail to cysts resulting from tick bites.[citation needed]

Ecology

Social structure and breeding habits

Female giraffes associate in groups of a dozen or so members, occasionally including a few younger males. Males tend to live in "bachelor" herds, with older males often leading solitary lives. Reproduction is polygamous, with a few older males impregnating all the fertile females in a herd. Male giraffes determine female fertility by tasting the female's urine in order to detect estrus, in a multi-step process known as the flehmen response.

Reproduction

Giraffe gestation lasts between 14 and 15 months, after which a single calf is born. The mother gives birth standing up and the embryonic sack usually bursts when the baby falls to the ground. Newborn giraffes are about 1.8 metres tall. Within a few hours of being born, calves can run around and are indistinguishable from a week-old calf; however, for the first two weeks, they spend most of their time lying down, guarded by the mother. The young can fall prey to lions, leopards, hyenas, and African Wild Dogs. It has been speculated that their characteristic spotted pattern provides a certain degree of camouflage. Only 25 to 50% of giraffe calves reach adulthood; the life expectancy is between 20 and 25 years in the wild and 28 years in captivity.(Encyclopedia of Animals).

Necking

The males often engage in necking, which has been described as having various functions. One of these is combat. These battles can be fatal, but are more often less severe. The longer a neck is, and the heavier the head at the end of the neck, the greater force a giraffe will be able to deliver in a blow. It has also been observed that males that are successful in necking have greater access to estrous females, so that the length of the neck may be a product of sexual selection.[5]

After a necking duel, a giraffe can land a powerful blow with his head occasionally knocking a male opponent to the ground. These fights rarely last more than a few minutes or end in physical harm.

Other behaviour

Food and Feeding

The giraffe browses on the twigs of trees, preferring trees of the genus Mimosa; but it appears that it can live without inconvenience on other vegetable food. A giraffe can eat 63 kg (140 lb) of leaves and twigs daily. As ruminants, they first chew their food, swallow for processing and then visibly regurgitate the semi-digested cud up their necks and back into the mouth, in order to chew again. This process is usually repeated several times for each mouthful.

Pace

The pace of the giraffe is an amble, though when pursued it can run extremely fast. It can not sustain a lengthened chase. Its leg length compels an unusual gait with the left legs moving together followed by right (similar to pacing) at low speed, and the back legs crossing outside the front at high speed. The giraffe defends itself against threats by kicking with great force. A single well-placed kick of an adult giraffe can shatter a lion's skull or break its spine.

Sleep

The giraffe has one of the shortest sleep requirements of any mammal, which is between 10 minutes and two hours in a 24-hour period, averaging 1.9 hours per day.[6] This has led to the myth that giraffes cannot lie down and that if they do so, they will die.

Cleaning

A giraffe will clean off any bugs that appear on its face with its extremely long tongue (about 18 in/45 cm). The tongue is tough on account of the giraffe's diet, which can include thorns from the trees that they eat. In Southern Africa, giraffes are partial to all acacias, especially Acacia erioloba, and possess a specially-adapted tongue and lips that are tough enough to withstand, or even ignore the vicious thorns of this plant.

Sounds

Giraffes are thought to be mute; however, although generally quiet, they have been heard to grunt, snort and bleat. Recent research has shown evidence that the animal communicates at an infrasound level.[7]

In art and culture

Giraffes can be seen in paintings, including the famous painting of a giraffe which was taken from Africa to China by Admiral Zheng He in 1414. The giraffe was placed in a Ming Dynasty zoo.

The Medici giraffe was a giraffe presented to Lorenzo de Medici in 1486. It caused a great stir on its arrival in Florence, being reputedly the first living giraffe to be seen in Italy since the days of Ancient Rome. Another famous giraffe, called Zarafa, was brought from Africa to Paris in the early 1800s and kept in a menagerie for 18 years.

Notable fictional giraffes include:

- Toys "R" Us mascot Geoffrey Giraffe. He was normally portrayed as a cartoon giraffe but in the 2001 commercials he was portrayed as a real-life giraffe who talks; an animatronic version of Geoffrey the Giraffe (created by Stan Winston Studios), was voiced by Jim Hanks in commercials for radio and television.

- Longrack of the Transformers universes

- Girafarig from the Pokémon Franchise

- Melman from Madagascar

Giraffes have also appeared as backgound characters in various other animated works such as Dumbo and The Lion King.

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ San Diego Zoo giraffe fact sheet Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ^ http://www.eaudrey.com/myth/camelopard.htm

- ^ http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-giraffe.html

- ^ Robert E. Simmons and Lue Scheepers: Winning by a neck: Sexual selection in the evolution of giraffe. The American Naturalist, 148 (1996): pp. 771-786.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/science/humanbody/sleep/articles/whatissleep.shtml

- ^ http://www.animalvoice.com/Giraffe.htm

External links

- -Video- Giraffe birth at the San Francisco Zoo

- Giraffes: Wildlife summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- ARKive - images and movies of the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis).

- Introduction to the history of the Giraffe in Middle Ages (French)

- Animal Diversity Web - Giraffa camelopardalis

- Giraffe Central web directory

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species

- PBS Nature: Tall Blondes (Giraffes)

- Giraffe Pictures and Observations

- Matt's World of Wicked Giraffes

- Mating System

- Giraffe Info Sheet

- Long-term suppression of fertility in female giraffe using the GnRH agonist deslorelin as a long-acting implant