To Live and Die in L.A. (film): Difference between revisions

Cleaned-up article in general |

LAX has airport POLICE, not security |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

The backwards car chase on a [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] freeway was William Friedkin's attempt to outdo the car chase from his [[1971 in film|1971]] film, ''[[The French Connection (film)|The French Connection]].''<ref>[http://www.24liesasecond.com/site2/index.php?page=2&task=index_onearticle.php&Column_Id=74 Crowley Michael K]. "Watching Under the Influence: ''To Live and Die in L.A.''," film analysis, [[August 12]], [[2004]].</ref> |

The backwards car chase on a [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] freeway was William Friedkin's attempt to outdo the car chase from his [[1971 in film|1971]] film, ''[[The French Connection (film)|The French Connection]].''<ref>[http://www.24liesasecond.com/site2/index.php?page=2&task=index_onearticle.php&Column_Id=74 Crowley Michael K]. "Watching Under the Influence: ''To Live and Die in L.A.''," film analysis, [[August 12]], [[2004]].</ref> |

||

The shot of William L. Petersen running along the metal railings of a moving sidewalk at the [[Los Angeles International Airport]] (LAX) got the filmmakers into trouble with the airport |

The shot of William L. Petersen running along the metal railings of a moving sidewalk at the [[Los Angeles International Airport]] (LAX) got the filmmakers into trouble with the airport police. The airport had prohibited this action, mainly for Petersen's safety, as they felt that their insurance wouldn't have covered him had he hurt himself. |

||

[[Image:Rickmasters.jpg|right|thumb|200px|[[Willem Dafoe]] as Rick Masters making fake money.]] |

[[Image:Rickmasters.jpg|right|thumb|200px|[[Willem Dafoe]] as Rick Masters making fake money.]] |

||

Though the film's producers utilized the knowledge of a convicted counterfeiter on the shoot, they claimed that they "stretched the law" by doing so, and by creating what some on the set claim to be "actual" counterfeit money, at least some—and perhaps all—[[currency]] used in the film reads "This note is not legal tender for all debts, public and private." This is most noticeable during a [[close-up]] shot when Agent John Vukovich erases a bill on an [[LAX]] ticket counter. |

Though the film's producers utilized the knowledge of a convicted counterfeiter on the shoot, they claimed that they "stretched the law" by doing so, and by creating what some on the set claim to be "actual" counterfeit money, at least some—and perhaps all—[[currency]] used in the film reads "This note is not legal tender for all debts, public and private." This is most noticeable during a [[close-up]] shot when Agent John Vukovich erases a bill on an [[LAX]] ticket counter. |

||

Revision as of 11:24, 19 July 2008

- This article is about the 1985 film. For other uses of the title, see To Live and Die in L.A. (disambiguation).

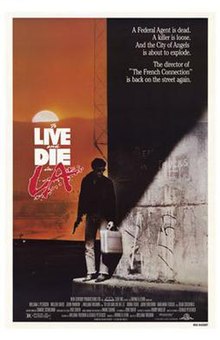

| To Live and Die in L.A. | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Written by | Story: Gerald Petievich Screenplay: William Friedkin Gerald Petievich |

| Produced by | Executive Producer: Samuel Schulman Producer: Irving H. Levin Bud S. Smith |

| Starring | William L. Petersen Willem Dafoe John Pankow Dean Stockwell John Turturro |

| Cinematography | Robby Müller |

| Music by | Wang Chung |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date | November 1 1985 |

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) is a American neo-noir crime film directed by William Friedkin and based on the novel written by former Secret Service agent Gerald Petievich, who co-wrote the screenplay with Friedkin. The drama features William L. Petersen, Willem Dafoe, John Turturro, John Pankow, among others. Wang Chung composed and performed the original music soundtrack. [1]

The film tells the story of the lengths to which two Secret Service agents go to arrest a counterfeiter.

Plot

Richard Chance (Petersen) is a Secret Service agent for the U.S. Treasury with a reputation in the department for reckless behavior.

His partner, Jimmy Hart (Michael Greene) is days away from retirement, but takes on one last mission to investigate counterfeiter Rick Masters (Dafoe). After Hart is killed by Masters' bodyguard, Chance is outraged and seeks revenge. Chance explains his outlook to his new partner, John Vukovich (Pankow) this way:

- Let me tell you something, amigo. I'm gonna bag Masters, and I don't give a shit how I do it.

The two T-men try to track down Masters, to no avail. Chance and Vukovich finally engage Masters by posing as potential counterfeiting clients interested in Masters' services.

Chance and Vukovich eventually break the law in their relentless pursuit of Masters. In order to get enough money to convince Masters that they are "real" clients, they kidnap and steal the money from a man who, unbeknownst to them, is an undercover F.B.I. agent. In a wild chase through the streets and freeways of Los Angeles. The F.B.I. agent is accidentally shot to death by his own men; which is covered-up by the F.B.I. and pinned on Chance and Vukovich.

Later, Chance once again meets with Masters, and pays him the "front money" that Masters has requested. The two agents go through with the transaction, even when Masters implies that he knows they stole the money from the F.B.I. undercover agent. During a set-up transaction, Chance tries to arrest Masters and his bodyguard, but the bodyguard pulls a shotgun from a locker and shoots Chance in the face, at the same time Chance shoots the bodyguard in the chest. They both die.

Masters briefly gets away, but Vukovich gives chase, eventually locating Masters at a warehouse Masters uses to produce his counterfeit money. At the time of Vukovich's arrival, Masters has already set fire to the contents of the warehouse. Vukovich confronts Masters and during a brief struggle, Vukovich is knocked unconscious. Masters covers Vukovich with shredded paper and just before Masters lights Vukovich on fire, Vukovich recovers and shoots Masters, who then drops his lighter and lights himself ablaze in the process. Vukovich survives and Masters perishes in the blaze.

In the event of Masters' death, Grimes (Masters' attorney) gives his estate to his girlfriend, Bianca. Without showing much remorse, she rides away in Masters' black Ferrari with a co-worker named Serena, whom they had a threesome with earlier in the film. In the last scene, Vukovich pays Chance's informant, Ruth, a visit, just as she's packing up to leave L.A., for good. He mentions Chance's death, that she knew the man they stole the advance money from was FBI, and that Chance left her with the leftover front money that his agency now wants back. All this leads to a surprise for Ruth: "You're working for me now". And with that, Chance lives on through Vukovich.

Cast

- William Petersen as Richard Chance

- Willem Dafoe as Eric "Rick" Masters

- John Pankow as John Vukovich

- Debra Feuer as Bianca Torres

- John Turturro as Carl Cody

- Darlanne Fluegel as Ruth Lanier

- Dean Stockwell as Bob Grimes

- Steve James as Jeff Rice

- Robert Downey Sr. as Thomas Bateman

- Michael Greene as Jim Hart

- Christopher Allport as Max Waxman

- Jack Hoar as Jack

- Valentin de Vargas as Judge Filo Cedillo

- Dwier Brown as Doctor

- Michael Chong as Thomas Ling

- Jane Leeves as Serena (credited as Jane Leaves)

Production

The climactic scene in which Chance is killed was not very well-received by MGM executives, according to William Friedkin on the Special Edition DVD. To satisfy the studio heads, he shot a second ending, in which Chance is shot in the stomach and lives, and then a different scene in which Chance and Vukovich, for reasons unexplained, are transferred to Alaska, and watch their boss Thomas Bateman being interviewed on television. Friedkin was disgusted by the new ending, and kept the original.[2]

The backwards car chase on a Los Angeles freeway was William Friedkin's attempt to outdo the car chase from his 1971 film, The French Connection.[3]

The shot of William L. Petersen running along the metal railings of a moving sidewalk at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) got the filmmakers into trouble with the airport police. The airport had prohibited this action, mainly for Petersen's safety, as they felt that their insurance wouldn't have covered him had he hurt himself.

Though the film's producers utilized the knowledge of a convicted counterfeiter on the shoot, they claimed that they "stretched the law" by doing so, and by creating what some on the set claim to be "actual" counterfeit money, at least some—and perhaps all—currency used in the film reads "This note is not legal tender for all debts, public and private." This is most noticeable during a close-up shot when Agent John Vukovich erases a bill on an LAX ticket counter.

Filming locations

Parts of the film were shot in Los Angeles: Nickerson Gardens in Watts, and parts of East Los Angeles. Other locations include: Los Angeles International Airport; Malibu; Union Station, Los Angeles; Vincent Thomas Bridge, San Pedro; and Wilmington, Los Angeles.

Reception

The film premiered in the United States on November 1, 1985. It was screened at various film festivals, including: the Cognac Festival du Film Policier, France; the Noir in Festival, Italy; the Turin Film Festival, Italy; and others.

The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 86% of critics gave the film a "Fresh" rating, based on twenty-two reviews.[4] Roger Ebert, film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, liked the film's screenplay, the action, the acting, and the direction, and wrote, "[T]he movie is also first-rate. The direction is the key. Friedkin has made some good movies...and some bad ones. This is his comeback, showing the depth and skill of the early pictures. The central performance is by William L. Petersen, a Chicago stage actor who comes across as tough, wiry and smart. He has some of the qualities of a Steve McQueen, with more complexity. Another strong performance in the movie is by Willem Dafoe as the counterfeiter, cool and professional as he discusses the realities of his business."[5]

Critic Janet Maslin was dismissive of the film, and wrote, "Today, in the dazzling, superficial style that Mr. Friedkin has so thoroughly mastered, it's the car chases and shootouts and eye-catching settings that are truly the heart of the matter." She also thought the work of Willem Dafoe would be forever typecast by this film when she added, "he's a fine actor with a face that will bring him villain's work forever."[6]

Wesley Morris, critic for The San Francisco Examiner, wrote in 1999 the film was Friedkin's best moment in filmmaking, "Sure, the Reagan-era exoticization of painters and extras salivating over the cash they count are as dated as the Wang Chung synth score, but To Live and Die in L.A. is as urgent and exhilaratingly paced as anything William Friedkin's done ... Some of the best crook-on-crook, cop-on-crook banter there ever was and John Turturro's best cursing in a motion picture . . . the six-lane rush-hour car chase that would make Popeye Doyle crash and burn . . . The only problem is that Friedkin would never get any better than this."[7]

The staff at Variety magazine were not impressed with the film and wrote that it was over the top, "To Live and Die in L.A. looks like a rich man's Miami Vice. William Friedkin's evident attempt to fashion a West Coast equivalent of his 1971 The French Connection is engrossing and diverting enough on a moment-to-moment basis but is overtooled ... Friedkin keeps dialog to a minimum, but what conversation there is proves wildly overloaded with streetwise obscenities, so much so that it becomes something of a joke. [Pic is based on the novel by Gerald Petievich, who co-scripted.]"[8]

Although a number of critics, and a good portion of the audience, remained somehow unimpressed by the movie when it first premiered, it appears to have aged fairly better than most of its contemporary neo-noir fare, and the expectation set upon its DVD release was symptomatic of a well-established cult following. It appears that the lukewarm box-office reception in 1985 owed at least partly to the film's grim, bleak and cynical tone, perhaps out of context during the time in which it premiered -- not because the film's antics were necessarily outdated in the mid-80s, but because the film's tinge of nihilism was far beyond aesthetic and affected the plot itself: there is not a single character nor action apparently driven by altruism, selflessness or an established sense of moral justice.[9][10] All this is confirmed by the film's anticlimactic outbursts of violence and especially by the ending, both hardly in tune with the subtly moralistic undertones of most of the action films of the decade.

An ostensible fact, perhaps indicative of this collective perception, is that most of the recent reviews of the film are punctuated by one-liners such as "A sun-bleached study in corruption and soul-destroying brutality"[11]. This reputation for grittiness, misanthropy and pessimism has accompanied Friedkin throughout his career [12][13].

Awards

Wins

- Cognac Festival du Film Policier: Audience Award; William Friedkin; 1986.

- Stuntman Awards: Stuntman Award; Best Feature Film Vehicular Stunt, Dick Ziker and Eddy Donnol; Most Feature Film Spectacular Sequence, Dick Ziker; 1986.

DVD release

A DVD was released by MGM Entertainment on December 2, 2003. The DVD contains a new restored wide-screen transfer, an audio commentary featuring director Friedkin where he relates stories about the making of the movie, a half-hour documentary featuring the main characters, a deleted scene that involves actor John Pankow, and an alternate ending Friedkin refused to use.[14]

Soundtrack

An original motion picture soundtrack was released on September 30, 1985, by Geffen Records. The album contained eight tracks. The album’s title song, "To Live and Die in L.A.," made it on the Billboard Hot 100 where it peaked at #41 in the United States.

William Friedkin chose Wang Chung to compose the soundtrack because the band "stands out from the rest of contemporary music... What they finally recorded has not only enhanced the film, it has given it a deeper, more powerful dimension." This note was included in the album's back cover.[15]

References

Notes

- ^ To Live and Die in L.A. at IMDb.

- ^ To Live and Die in L.A., Special Edition DVD, 2003.

- ^ Crowley Michael K. "Watching Under the Influence: To Live and Die in L.A.," film analysis, August 12, 2004.

- ^ To Live and Die in L.A. at Rotten Tomatoes. Last accessed: January 22, 2008.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. The Chicago Sun-Times, film review, November 1, 1985.

- ^ Maslin, Janet. The New York Times, film review, "From Friedkin," November 1, 1985.

- ^ Morris, Wesley. The San Francisco Examiner, film review, ""To Live and Die in L.A.': Friedkin's finest hour," April 16, 1999. Last accessed: December 28, 2007.

- ^ Variety. Film review, November 1, 1985. Last accessed: December 28, 2007.

- ^ Editorial review[1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ Reel Film Reviews. DVD review, December 3 2003.

- ^ Wang Chung web site. Last accessed: December 6 2007.

External links

- To Live and Die in L.A. at IMDb

- To Live and Die in L.A.. at AllMovie

- To Live and Die in L.A. film review and analysis at "24 Lies A Second"

- William Petersen image in film (press-kit photograph)