Medicare (United States): Difference between revisions

| Line 136: | Line 136: | ||

In 2002, payment rates were cut by 4.8%. In 2003, payment rates were scheduled to be reduced by 4.4%. However, Congress boosted the cumulative SGR target in the Consolidated Appropriation Resolution of 2003 (P.L. 108-7), allowing payments for physician services to rise 1.6%. In 2004 and 2005, payment rates were again scheduled to be reduced. The Medicare Modernization Act (P.L. 108-173) increased payments 1.5% for those two years. |

In 2002, payment rates were cut by 4.8%. In 2003, payment rates were scheduled to be reduced by 4.4%. However, Congress boosted the cumulative SGR target in the Consolidated Appropriation Resolution of 2003 (P.L. 108-7), allowing payments for physician services to rise 1.6%. In 2004 and 2005, payment rates were again scheduled to be reduced. The Medicare Modernization Act (P.L. 108-173) increased payments 1.5% for those two years. |

||

In 2006, the SGR mechanism was scheduled to decrease physician payments by 4.4%. (This number results from a 7% decrease in physician payments times a 2.8% inflation adjustment increase.) Congress overrode this decrease in the Deficit Reduction Act (P.L. 109-362), and held physician payments in 2006 at their 2005 levels. Without further continuing congressional intervention, the SGR is expected to decrease physician payments from 25% to 35% over the next several years. |

In 2006, the SGR mechanism was scheduled to decrease physician payments by 4.4%. (This number results from a 7% decrease in physician payments times a 2.8% inflation adjustment increase.) Congress overrode this decrease in the Deficit Reduction Act (P.L. 109-362), and held physician payments in 2006 at their 2005 levels. Similary, another congressional act held 2007 payments at their 2006 levels, and HR 6331 held 2008 physician payments to their 2007 levels, and provided for a 1.1% increase in physician payments in 2009. Without further continuing congressional intervention, the SGR is expected to decrease physician payments from 25% to 35% over the next several years. |

||

MFS has been criticized for not paying doctors enough because of the low conversion factor. By adjustments to the MFS conversion factor, it is possible to |

MFS has been criticized for not paying doctors enough because of the low conversion factor. By adjustments to the MFS conversion factor, it is possible to make global adjustments in payments to all doctors.<ref>[http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdoc.cfm?index=7425&type=1 Medicare's Physician Payment Rates and the Sustainable Growth Rate].(PDF) ''CBO TESTIMONY Statement of Donald B. Marron, Acting Director''. [[July 25]], [[2006]].</ref> |

||

==== Office medication reimbursement ==== |

==== Office medication reimbursement ==== |

||

Revision as of 11:35, 22 July 2008

- This article refers to Medicare, a United States health insurance program. For similarly named programs in other countries, see Medicare.

Medicare is a social insurance program administered by the United States government, providing health insurance coverage to people who are aged 65 and over, or who meet other special criteria. It was originally signed into law on July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon B. Johnson as amendments to Social Security legislation. At the bill-signing ceremony President Johnson enrolled former President Harry S. Truman as the first Medicare beneficiary and presented him with the first Medicare card.[1]

Administration

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), a component of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), administers Medicare, Medicaid, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). Along with the Departments of Labor and Treasury, CMS also implements the insurance reform provisions of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). The Social Security Administration is responsible for determining Medicare eligibility and processing premium payments for the Medicare program.

The Chief Actuary of CMS is responsible for providing accounting information and cost-projections to the Medicare Board of Trustees in order to assist them in assessing the financial health of the program. The Board is required by law to issue annual reports on the financial status of the Medicare Trust Funds, and those reports are required to contain a statement of actuarial opinion by the Chief Actuary.[2][3]

Since the beginning of the Medicare program, CMS has contracted with private companies to assist with administration. These contractors are commonly already in the insurance or health care area. Contracted processes include claims and payment processing, call center services, clinician enrollment, and fraud investigation.

Taxes imposed to finance Medicare

Medicare is partially financed by payroll taxes imposed by the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) and the Self-Employment Contributions Act of 1954. In the case of employees, the tax is equal to 2.9% (1.45% withheld from the worker and a matching 1.45% paid by the employer) of the wages, salaries and other compensation in connection with employment. Until December 31, 1993, the law provided a maximum amount of wages, etc., on which the Medicare tax could be imposed each year. Beginning January 1, 1994, the compensation limit was removed. In the case of self-employed individuals, the tax is 2.9% of net earnings from self-employment, and the entire amount is paid by the self-employed individual.

Eligibility

In general, individuals are eligible for Medicare if they are a U.S. citizen or have been a permanent legal resident for 5 continuous years, and they are 65 years or older, or they are under 65, disabled and have been receiving either Social Security or the Railroad Retirement Board disability benefits for at least 24 months, or they get continuing dialysis for permanent kidney failure or need a kidney transplant, or they are eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance and have Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS-Lou Gehrig's disease).

Many beneficiaries are dual-eligible. This means they qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. In some states for those making below a certain income, Medicaid will pay the beneficiaries' Part B premium for them (most beneficiaries have worked long enough and have no Part A premium), and also pay any drugs that are not covered by Part D.

In 2007, Medicare provided health care coverage for 43 million Americans. Enrollment is expected to reach 77 million by 2031, when the baby boom generation is fully enrolled.[4]

Benefits

There are separate lines with for Part A and Part B, each with its own date.

There is no lines for Part C or D, as a separate card is issued for those benefits by the private insurance company.

The original Medicare program has two parts: Part A (Hospital Insurance), and Part B (Medical Insurance). Only a few special cases exist where prescription drugs are covered by original Medicare, but as of January 2006, Medicare Part D provides more comprehensive drug coverage. Medicare Advantage plans are another way for beneficiaries to receive their Part A, B and D benefits. All Medicare benefits are subject to medical necessity.

Part A: Hospital Insurance

Part A covers hospital stays (including stays in a skilled nursing facility) if certain criteria are met:

- The hospital stay must be at least three days, three midnights, not counting the discharge date.

- The nursing home stay must be for something diagnosed during the hospital stay or for the main cause of hospital stay. For instance, a hospital stay for a broken hip and then a nursing home stay for physical therapy would be covered.

- If the patient is not receiving rehabilitation but has some other ailment that requires skilled nursing supervision then the nursing home stay would be covered.

- The care being rendered by the nursing home must be skilled. Medicare part A does not pay for custodial, non-skilled, or long-term care activities, including activities of daily living (ADLs) such as personal hygiene, cooking, cleaning, etc.

The maximum length of stay that Medicare Part A will cover in a skilled nursing facility per ailment is 100 days. The first 20 days would be paid for in full by Medicare with the remaining 80 days requiring a co-payment (as of 2008, $128.00 per day). Many insurance companies have a provision for skilled nursing care in the policies they sell.

If a beneficiary uses some portion of their Part A benefit and then goes at least 60 days without receiving facility-based skilled services, the 100-day clock is reset and the person qualifies for a new 100-day benefit period.

Part B: Medical Insurance

Part B medical insurance helps pay for some services and products not covered by Part A, generally on an outpatient basis. Part B is optional and may be deferred if the beneficiary or their spouse is still actively working. There is a lifetime penalty (10% per year) imposed for not taking Part B if not actively working.

Part B coverage includes physician and nursing services, x-rays, laboratory and diagnostic tests, influenza and pneumonia vaccinations, blood transfusions, renal dialysis, outpatient hospital procedures, limited ambulance transportation, Immunosuppressive drugs for organ transplant recipients, chemotherapy, hormonal treatments such as lupron, and other outpatient medical treatments administered in a doctor's office. Medication administration is covered under Part B only if it is administered by the physician during an office visit.

Part B also helps with durable medical equipment (DME), including canes, walkers, wheelchairs, and mobility scooters for those with mobility impairments. Prosthetic devices such as artificial limbs and breast prosthesis following mastectomy, as well as one pair of eyeglasses following cataract surgery, and oxygen for home use is also covered.[5]

Complex rules are used to manage the benefit, and advisories are periodically issued which describe coverage criteria. On the national level these advisories are issued by CMS, and are known as National Coverage Determinations (NCD). Local Coverage Determinations (LCD) only apply within the multi-state area managed by a specific regional Medicare Part B contractor, and Local Medical Review Policies (LMRP) were superseded by LCDs in 2003. Coverage information is also located in the CMS Internet-Only Manuals (IOM), the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the Social Security Act, and the Federal Register.

Part C: Medicare Advantage plans

With the passage of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Medicare beneficiaries were given the option to receive their Medicare benefits through private health insurance plans, instead of through the original Medicare plan (Parts A and B). These programs were known as "Medicare+Choice" or "Part C" plans. Pursuant to the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, the compensation and business practices changed for insurers that offer these plans, and "Medicare+Choice" plans became known as "Medicare Advantage" (MA) plans.

Medicare has a standard benefit package that covers medically necessary care members can receive from nearly any hospital or doctor in the country. For people who choose to enroll in a Medicare private health plan, Medicare pays the private health plan a set amount every month for each member. Members may have to pay a monthly premium in addition to the Medicare Part B premium and generally pay a fixed amount (a copayment of $20, for example) every time they see a doctor. The copayment can be higher to see a specialist.

The private plans are required to offer a benefit “package” that is at least as good as Medicare’s and cover everything Medicare covers, but they do not have to cover every benefit in the same way. Plans that pay less than Medicare for some benefits, like skilled nursing facility care, can balance their benefits package by offering lower copayments for doctor visits. Private plans use some of the excess payments they receive from the government for each enrollee to offer supplemental benefits. Some plans put a limit on their members’ annual out-of-pocket spending on medical care, providing some insurance against catastrophic costs over $5,000, for example. But many plans use the excess subsidies to offer dental coverage and other services not covered by Medicare and can leave members exposed to high medical bills if they fall seriously ill. Private plan members can end up with unexpectedly high out-of-pocket costs.

In 2006 enrollees in Medicare Advantage Private Fee-for-Service plans were offered a net extra benefit value (the value of the additional benefits minus any additional premium) of $55.92 a month more than the traditional Medicare benefit package; enrollees in other Medicare Advantage plans were offered a net extra benefit value of $71.22 a month more.[6]

Medicare Advantage Plans that also include Part D prescription drug benefits are known as a Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug plan or a MAPD.

Enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans grew from 5.4 million in 2005 to 8.2 million in 2007. Enrollment grew by an additional 800,000 during the first four months of 2008. This represents 19% of Medicare beneficiaries. A third of beneficiaries with Part D coverage are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan. Medicare Advantage enrollment is higher in urban areas; the enrollment rate in urban counties is twice that in rural counties (22% vs. 10%). Almost all Medicare beneficiaries have access to at least two Medicare Advantage plans; most have access to three or more. The number of organizations offering Fee-for-Service plans has increased dramatically, from 11 in 2006 to almost 50 in 2008. Eight out of ten beneficiaries (82%) now have access to six or more Private Fee-for-Service plans.[7]

Part D: Prescription Drug plans

Medicare Part D went into effect on January 1, 2006. Anyone with Part A or B is eligible for Part D. It was made possible by the passage of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act. In order to receive this benefit, a person with Medicare must enroll in a stand-alone Prescription Drug Plan (PDP) or Medicare Advantage plan with prescription drug coverage (MA-PD). These plans are approved and regulated by the Medicare program, but are actually designed and administered by private health insurance companies. Unlike Original Medicare (Part A and B), Part D coverage is not standardized. Plans choose which drugs (or even classes of drugs) they wish to cover, at what level (or tier) they wish to cover it, and are free to choose not to cover some drugs at all. The exception to this is drugs that Medicare specifically excludes from coverage, including but not limited to benzodiazepines, cough suppressant and barbiturates.[8][9] Plans that cover excluded drugs are not allowed to pass those costs on to Medicare, and plans are required to repay CMS if they are found to have billed Medicare in these cases.[10]

It should be noted again for beneficiaries who are dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid eligible) Medicaid will pay for drugs not covered by part D of Medicare, such as benzodiazepines, and other restricted controlled substances.

Out-of-pocket costs

Neither Part A nor Part B pays for all of a covered person's medical costs. The program contains premiums, deductibles and co-pays, which the covered individual must pay out-of-pocket. Some people may qualify to have other governmental programs (such as Medicaid) pay premiums and some or all of the costs associated with Medicare.

Premiums

Most Medicare enrollees do not pay a monthly Part A premium, because they (or a spouse) have had 40 or more quarters in which they paid Federal Insurance Contributions Act taxes. Medicare-eligible persons who do not have 40 or more quarters of Medicare-covered employment may purchase Part A for a monthly premium of:

- $233.00 per month (2008) for those with 30-39 quarters of Medicare-covered employment, or

- $423.00 per month (in 2008) for those with less than 30 quarters of Medicare-covered employment and who are not otherwise eligible for premium-free Part A coverage.

All Medicare Part B enrollees pay an insurance premium for this coverage; the standard Part B premium for 2008 is $96.40 per month. A new income-based premium schema has been in effect for 2007, wherein Part B premiums are higher for beneficiaries with incomes exceeding $80,000 for individuals or $160,000 for married couples. Depending on the extent to which beneficiary earnings exceed the base income, these higher Part B premiums are $122.20, $160.90, $199.70, or $238.40 for 2008, with the highest premium paid by individuals earning more than $205,000, or married couples earning more than $410,000.[11]

Medicare Part B premiums are commonly deducted automatically from beneficiaries' monthly Social Security checks.

Part C and D plans may or may not charge premiums, at the programs' discretion. Part C plans may also choose to rebate a portion of the Part B premium to the member.

Deductible and coinsurance

Part A — For each benefit period, a beneficiary will pay:

- A Part A deductible of $1,024 (in 2008) for a hospital stay of 1-60 days.

- A $256 per day co-pay (in 2008) for days 61-90 of a hospital stay.

- A $512 per day co-pay (in 2008) for days 91-150 of a hospital stay, as part of their limited Lifetime Reserve Days.

- All costs for each day beyond 150 days[11]

- Coinsurance for a Skilled Nursing Facility is $128.00 per day (in 2008) for days 21 through 100 for each benefit period.

- A blood deductible of the first 3 pints of blood needed in a calendar year, unless replaced. There is a 3 pint blood deductible for both Part A and Part B, and these separate deductibles do not overlap.

Part B — After a beneficiary meets the yearly deductible of $135.00 (in 2008), they will be required to pay a co-insurance of 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for all services covered by Part B. They are also required to pay an excess charge of 15% for services rendered by non-participating Medicare providers.

The deductibles and coinsurance charges for Part C and D plans vary from plan to plan.

Medicare supplement (Medigap) policies

Some people elect to purchase a type of supplemental coverage, called a Medigap plan, to help fill in the holes in Original Medicare (Part A and B). These Medigap insurance policies are standardized by CMS, but are sold and administered by private companies. Some Medigap policies sold before 2006 may include coverage for prescription drugs. Medigap policies sold after the introduction of Medicare Part D on January 1, 2006 are prohibited from covering drugs.

Some have suggested that by reducing the cost-sharing requirements in the Medicare program, Medigap policies increase the use of health care by Medicare beneficiaries and thus increase Medicare spending. One recent study suggests that this concern may have been overstated due to methodological problems in prior research.[12]

Payment for services

Medicare contracts with regional insurance companies who process over one billion fee-for-service claims per year. In 2003, Medicare accounted for almost 13% of the entire federal budget. Based on the CMS projections, 33 cents of every dollar spent on health care in the U.S. is paid by Medicare and Medicaid (including State funding). Looked at from three different perspectives, 61 cents of every dollar spent on nursing homes, 47 cents of every dollar received by U.S. hospitals, and 27 cents of every dollar spent on physician services is funded by Medicare or Medicaid.

Reimbursement for Part A services

For institutional care such as hospital and nursing home care, Medicare uses prospective payment systems. A prospective payment system is one in which the health care institution receives a set amount of money for each episode of care provided to a patient, regardless of the actual amount of care used. The actual allotment of funds is based on a list of diagnosis-related groups (DRG). The actual amount depends on the kind of diagnosis made at the hospital. There are some issues surrounding Medicare's use of DRGs because if the patient uses less care, the hospital gets to keep the remainder. This, in theory, should balance the costs for the hospital. However, if the patient uses more care, then the hospital has to cover its own losses. This results in the issue of "upcoding," when a physician makes a more severe diagnosis to hedge against accidental costs.

Reimbursement for Part B services

Payment for physician services under Medicare has evolved since the program was created in 1965. Initially, Medicare compensated physicians based on the physician's charges, and allowed physicians to bill Medicare beneficiaries the amount in excess of Medicare's reimbursement. In 1975, annual increases in physician fees were limited by the Medicare Economic Index (MEI). The MEI was designed to measure changes in costs of physician's time and operating expenses, adjusted for changes in physician productivity. From 1984 to 1991, the yearly change in fees was determined by legislation. This was done because physician fees were rising faster than projected.

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1989 made several changes to physician payments under Medicare. Firstly, it introduced the Medicare Fee Schedule, which took effect in 1992. Secondly, it limited the amount Medicare non-providers could balance bill Medicare beneficiaries. Thirdly, it introduced the Medicare Volume Performance Standards (MVPS) as a way to control costs.[13]

On January 1, 1992, Medicare introduced the Medicare Fee Schedule (MFS). The MFS assigned Relative Value Units (RVUs) for each procedure from the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS). The Medicare reimbursement for a physician was the product of the RVU for the procedure, a Geographic Adjustment Factor (GAF) for geographic variations in payments, and a global Conversion Factor (CF) which converts RBRVS units to dollars.

From 1992 to 1997, adjustments to physician payments were adjusted using the MEI and the MVPS, which essentially tried to compensate for the increasing volume of services provided by physicians by decreasing their reimbursement per service.

In 1998, Congress replaced the VPS with the Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR). This was done because of highly variable payment rates under the MVPS. The SGR attempts to control spending by setting yearly and cumulative spending targets. If actual spending for a given year exceeds the spending target for that year, reimbursement rates are adjusted downward by decreasing the Conversion Factor (CF) for RBRVS RVUs.

Since 2002, actual Medicare Part B expenditures have exceeded projections.

In 2002, payment rates were cut by 4.8%. In 2003, payment rates were scheduled to be reduced by 4.4%. However, Congress boosted the cumulative SGR target in the Consolidated Appropriation Resolution of 2003 (P.L. 108-7), allowing payments for physician services to rise 1.6%. In 2004 and 2005, payment rates were again scheduled to be reduced. The Medicare Modernization Act (P.L. 108-173) increased payments 1.5% for those two years.

In 2006, the SGR mechanism was scheduled to decrease physician payments by 4.4%. (This number results from a 7% decrease in physician payments times a 2.8% inflation adjustment increase.) Congress overrode this decrease in the Deficit Reduction Act (P.L. 109-362), and held physician payments in 2006 at their 2005 levels. Similary, another congressional act held 2007 payments at their 2006 levels, and HR 6331 held 2008 physician payments to their 2007 levels, and provided for a 1.1% increase in physician payments in 2009. Without further continuing congressional intervention, the SGR is expected to decrease physician payments from 25% to 35% over the next several years.

MFS has been criticized for not paying doctors enough because of the low conversion factor. By adjustments to the MFS conversion factor, it is possible to make global adjustments in payments to all doctors.[14]

Office medication reimbursement

Chemotherapy and other medications dispensed in a physician's office are reimbursed according to the Average Sales Price, a number computed by taking the total dollar sales of a drug as the numerator and the number of units sold nationwide as the denominator. The current reimbursement formula is known as "ASP+6" since it reimburses physicians at 106% of the ASP of drugs. Pharmaceutical company discounts and rebates are included in the calculation of ASP, and tend to reduce it. ASP+6 superseded Average Wholesale Price in 2005, after a 2004 front-page New York Times article drew attention to the inaccuracies of Average Wholesale Price calculations. Average Wholesale Price (AWP) reimbursement tended to be more favorable for physicians, since it was an arbitrary number provided by the pharmaceutical company to CMS. Since the change, some outpatient chemotherapy drugs are "underwater," since the wholesale price from drug distributors may be higher than ASP+6 for some drugs.[citation needed] Stakeholders are involved in active discussions with the United States Congress to address this issue.[citation needed]

Costs and funding challenges

According to the 2004 "Green Book" of the House Ways and Means Committee, Medicare expenditures from the American government were $256.8 billion in fiscal year 2002. Beneficiary premiums are highly subsidized, and net outlays for the program, accounting for the premiums paid by subscribers, were $230.9 billion.

Medicare spending is growing steadily in both absolute terms and as a percentage of the federal budget. Total Medicare spending reached $440 billion for fiscal year 2007, or 16 percent of all federal spending. The only larger categories of federal spending are Social Security and defense. Given the current pattern of spending growth, maintaining Medicare's financing over the long-term may well require significant changes.[15]

According to the 2008 report by the board of trustees for Medicare and Social Security, Medicare will spend more than it brings in from taxes this year (2008). The Medicare hospital insurance trust fund will become insolvent by 2019.[16][17][18][15] Shortly after the release of the report, the Chief Actuary testified that the insolvency of the system could be pushed back by 18 months if Medicare Advantage plans were paid at the same rate as the traditional fee-for-service program. He also testified that the 10-year cost of Medicare drug benefit is 37% lower than originally projected in 2003, and 17% percent lower than last year's projections.[19]

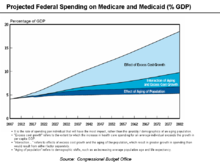

Spending on Medicare and Medicaid is projected to grow dramatically in coming decades. While the same demographic trends that affect Social Security also affect Medicare, rapidly rising medical prices appear a more important cause of projected spending increases. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has indicated that: "Future growth in spending per beneficiary for Medicare and Medicaid—the federal government’s major health care programs—will be the most important determinant of long-term trends in federal spending. Changing those programs in ways that reduce the growth of costs—which will be difficult, in part because of the complexity of health policy choices—is ultimately the nation’s central long-term challenge in setting federal fiscal policy." Further, the CBO also projects that "total federal Medicare and Medicaid outlays will rise from 4 percent of GDP in 2007 to 12 percent in 2050 and 19 percent in 2082—which, as a share of the economy, is roughly equivalent to the total amount that the federal government spends today. The bulk of that projected increase in health care spending reflects higher costs per beneficiary rather than an increase in the number of beneficiaries associated with an aging population."[20]

Financial viability

Richard W. Fisher, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas has remarked that in order to "cover the unfunded liability" for the Medicare program today, "you would be stuck with an $85.6 trillion bill" which is "more than six times the annual output of the entire U.S. economy."[21]

Aging of the population

The fundamental problem is that the ratio of workers paying Medicare taxes to retirees drawing benefits is shrinking at the same time that the price of health care services per person is increasing.[22][23] Currently there are 3.9 workers paying taxes into Medicare for every older American receiving services. By 2030, as the baby boom generation retires, that is projected to drop to 2.4 workers for each beneficiary. Medicare spending is expected to grow by about 7 percent per year for the next 10 years.[24] As a result, the financing of the program is out of actuarial balance, presenting serious challenges in both the short-term and long-term.[18][15]

Fraud and waste

Part of the cost of Medicare is attributable to fraud, which government auditors estimate costs Medicare billions of dollars a year.[25][26] The Government Accountability Office lists Medicare as a "high-risk" government program in need of reform, in part because of its vulnerability to fraud and partly because of its long-term financial problems.[27] A Washington Post story from June of 2008 reported that Medicare fraud is a growing problem. Limited resources mean that fewer than 5% of Medicare claims are audited. The annual cost to taxpayers of Medicare fraud is estimated to be over $60 billion.[28]

Criticism

Medicare faces continuing financial issues. In its 2006 annual report to Congress, the Medicare Board of Trustees reported that the program's hospital insurance trust fund could run out of money by 2018. The trustees have made such projections in the past, but this one was bleaker than the outlook reported in 2005.[29]

Popular opinion surveys show that the public views Medicare’s problems as serious, but not as urgent as other concerns. In January 2006, the Pew Research Center found 62 percent of the public said addressing Medicare’s financial problems should be a high priority for the government, but that still put it behind other priorities.[30] Surveys suggest that there’s no public consensus behind any specific strategy to keep the program solvent.[31]

Quality of beneficiary services

A study by the Government Accountability Office evaluated the quality of responses given by Medicare contractor customer service representatives to provider (physician) questions. The evaluators assembled a list of questions, which they asked during a random sampling of calls to Medicare contractors. The rate of complete, accurate information provided by Medicare customer service representatives was 15%.[32]

Hospital accreditation

In most states the Joint Commission, a private, non-profit organization for accrediting hospitals, possesses a monopoly over whether or not a hospital is able to participate in Medicare, as currently there are no competitor organizations recognized by CMS. An attempt by TÜV Healthcare Specialists to provide a hospital accreditation option was denied in 2006. [33] Rebecca Wise, CEO of TÜVHS, has said "Choice and competition are the hallmarks of a free market.... Can you think of an industry with a more profound impact on our lives than healthcare? Yet there is a much higher chance of you getting the wrong dosage of medicine in a hospital than there is of a manufacturer putting the wrong chip on a circuit board. It’s a failure of the system not the people." [34]

Beyond hospitals and hospital accreditation, there are now a number of alternative American organizations possessing healthcare-related deeming power for Medicare. These include the Community Health Accreditation Program, the Accreditation Commission for Health Care, the Compliance Team and the Healthcare Quality Association on Accreditation.

Physician residency

Medicare funds the vast majority of residency training in the US. This tax-based financing covers resident salaries and benefits through payments called Direct Medical Education payments. Medicare also uses taxes for Indirect Medical Education, a subsidy paid to teaching hospitals in exchange for training resident physicians.[35] Overall funding levels, however, have remained frozen over the last ten years, creating a bottleneck in the training of new physicians in the US.[36] Meanwhile, the US population continues to grow, leading to greater demand for physicians. At the same time the cost of medical services continue rising rapidly and many geographic areas face physician shortages, both trends suggesting the supply of physicians remains too low.[37] Medicare finds itself in the odd position of having assumed control of graduate medical education, currently facing major budget constraints, and as a result, freezing funding for graduate medical education, as well as for physician reimbursement rates.[38] This halt in funding in turn exacerbates the exact problem Medicare sought to solve in the first place: improving the availability of medical care. In response, teaching hospitals have resorted to alternative approaches to funding resident training, leading to the modest 4% total growth in residency slots from 1998-2004, despite Medicare funding having been frozen since 1996.[39]

Legislation and reform

- 1960 — PL 86-778 Social Security Amendments of 1960 (Kerr-Mill aid)

- 1965 — PL 89-97 Social Security Amendments of 1965, Establishing Medicare Benefits

- 1988 — PL 100-360 Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act of 1988

- 1997 — PL 105-33 Balanced Budget Act of 1997

- 2003 — PL 108-173 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act

President Bill Clinton attempted an overhaul of Medicare through his health care reform plan in 1993-1994 but was unable to get the legislation passed by Congress.

In 2003 Congress passed the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act, which President George W. Bush signed into law on December 8, 2003. Part of this legislation included filling gaps in prescription-drug coverage left by the Medicare Secondary Payer Act that was enacted in 1980. The 2003 bill strengthened the Workers' Compensation Medicare Set-Aside Program (WCMSA) that is monitored and administered by CMS.

On August 1, 2007, the U.S. House United States Congress voted to reduce payments to Medicare Advantage providers in order to pay for expanded coverage of children's health under the SCHIPS program. As of 2008, Medicare Advantage plans cost, on average, 13 percent more per person insured than direct payment plans.[40] Many health economists have concluded that payments to Medicare Advantage providers have been excessive. The Senate, after heavy lobbying from the insurance industry, declined to agree to the cuts in Medicare Advantage proposed by the House. President Bush subsequently vetoed the SCHIPS extension. [41]

Legislative oversight

- This table incorporates information available on the CMS Website[42]

See also

|

References

- ^ Social Security Online History Pages

- ^ "What Is the Role of the Federal Medicare Actuary?," American Academy of Actuaries, January 2002

- ^ "Social Insurance," Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 32, Actuarial Standards Board, January 1998

- ^ Overview

- ^ http://www.uihealthcare.com/topics/aging/agin3390.html Medicare: Part A & B

- ^ Mark Merlis, "The Value of Extra Benefits Offered by Medicare Advantage Plans in 2006," The Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2008

- ^ Marsha Gold, "Medicare Advantage in 2008," The Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2008

- ^ Product/Drug/Drug Category

- ^ Relationship between Part B and Part D Coverage

- ^ Report on the Medicare Drug Discount Card Program Sponsor McKesson Health Solutions, A-06-06-00022

- ^ a b 2008 Medicare & You handbook, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

- ^ Jeff Lemieux, Teresa Chovan, and Karen Heath, "Medigap Coverage And Medicare Spending: A Second Look," Health Affairs, Volume 27, Number 2, March/April 2008

- ^ Lauren A. McCormick, Russel T. Burge. Diffusion of Medicare's RBRVS and related physician payment policies - resource-based relative value scale - Medicare Payment Systems: Moving Toward the Future Health Care Financing Review. Winter, 1994.

- ^ Medicare's Physician Payment Rates and the Sustainable Growth Rate.(PDF) CBO TESTIMONY Statement of Donald B. Marron, Acting Director. July 25, 2006.

- ^ a b c Lisa Potetz, "Financing Medicare: an Issue Brief," the Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2008

- ^ Annual Federal Report Forecasts Medicare Funding Gap by 2019 - California Healthline

- ^ "2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARDS OF TRUSTEES OF THE FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE TRUST FUNDS," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, March 25, 2008

- ^ a b "Medicare’s Financial Condition: Beyond Actuarial Balance," American Academy of Actuaries, March 2008

- ^ "Medicare: Paying Medicare Advantage Plans Same Rates as Traditional Medicare Would Delay Program Insolvency by 18 Months, Medicare Actuary Says," Kaiser Daily Health Policy Report, Kaiser Family Foundation, April 02, 2008

- ^ CBO Testimony

- ^ Richard W. Fisher (2008-05-28). "Storms on the Horizon". Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

Medicare was a pay-as-you-go program from the very beginning, despite warnings from some congressional leaders—Wilbur Mills was the most credible of them before he succumbed to the pay-as-you-go wiles of Fanne Foxe, the Argentine Firecracker—who foresaw some of the long-term fiscal issues such a financing system could pose. Unfortunately, they were right.

Please sit tight while I walk you through the math of Medicare. As you may know, the program comes in three parts: Medicare Part A, which covers hospital stays; Medicare B, which covers doctor visits; and Medicare D, the drug benefit that went into effect just 29 months ago. The infinite-horizon present discounted value of the unfunded liability for Medicare A is $34.4 trillion. The unfunded liability of Medicare B is an additional $34 trillion. The shortfall for Medicare D adds another $17.2 trillion. The total? If you wanted to cover the unfunded liability of all three programs today, you would be stuck with an $85.6 trillion bill. That is more than six times as large as the bill for Social Security. It is more than six times the annual output of the entire U.S. economy. - ^ Medicare: Fact File

- ^ Medicare: Fact File

- ^ "2006 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplimentary Medical Insurance Trust Funds, 1 May 2006 (PDF)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ U.S. GAO - Report Abstract

- ^ http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d02546.pdf

- ^ ""High-Risk Series: An Update" U.S. Government Accountability Office, January 2003 (PDF)" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Carrie Johnson, "Medical Fraud a Growing Problem: Medicare Pays Most Claims Without Review," The Washington Post, June 13, 2008

- ^ 2006 MEDICARE TRUSTEES REPORT

- ^ Medicare: People's Chief Concerns

- ^ Medicare: Red Flags

- ^ http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d011141t.pdf

- ^ Quarterly Provider Updates

- ^ MedLaw.com :: New Competitor Takes On JCAHO Accreditation

- ^ Medicare funding for medical education: a waste of money?

- ^ Innovative funding opens new residency slots

- ^ Shortages of Medical Personnel at Community Health Centers - JAMA, March 1, 2006

- ^ Innovative funding opens new residency slots

- ^ Innovative funding opens new residency slots

- ^ Aliza Marcus, "Senate Vote on Doctor Fees Carries Risks for McCain", Bloomberg News, July 9, 2008

- ^ "House Passes Children’s Health Plan 225-204", New York Times, August 2, 2007]

- ^ http://www.cms.hhs.gov/OfficeofLegislation/COI/list.asp CMS Website, accessed 2/15/07

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. |

Governmental links - current

- CMS official web site at cms.hhs.gov

- Medicare at cms.hhs.gov

- Medicare.gov — the official website for people with Medicare

- Official Medicare publications at Medicare.gov — includes official publications about current Medicare benefits

- Medicare & You handbook for 2008 at Medicare.gov — includes information about current Medicare benefits

- Information about the 1-800-MEDICARE helpline from Medicare.gov — a 24X7 toll-free number to call with questions about Medicare

- Medicare Modernization Act at Medicare.gov

- Medicare Plan Choices at Medicare.gov — basic information about plan choices for Medicare beneficiaries, including MA Plans

- Prescription Drug Coverage homepage at Medicare.gov — a central location for Medicare's web-based information about the Part D benefit

- Landscape of plans — state-by-state breakdown of all plans available in an area, both stand-alone PDPs, as well as MA-PD plans

- Official Medicare publications at Medicare.gov — includes official publications about current Medicare benefits

- MyMedicare.gov — Medicare's secure online service where beneficiaries can access their own personal Medicare information

Governmental links - historical

- Medicare Is Signed Into Law page from ssa.gov — material about the bill-signing ceremony

- Historical Background and Development of Social Security from ssa.gov — includes information about Medicare

- Detailed Chronology of SSA from ssa.gov — includes information about Medicare

- Early Medicare poster from ssa.gov

Non-governmental links

- Congressional Research Service (CRS) Reports related to Medicare from the University of Texas Libraries

- Center for Medicare Advocacy — National education & advocacy organization.

- Medicare Rights Center — Education and advocacy organization.

- Medicare.org — Medicare information site including descriptions of Part A through D

- Medicare & Medicaid Resources — Medicare information site

- Kaiser Family Foundation — Wide range of free information, including a drug benefit calculator, about the Medicare program and other U.S. health issues.

- State Health Facts — Data on health care spending and utilization, including Medicare; provided by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

- Medicare - Alliance for Health Reform The nonpartisan, nonprofit Alliance for Health Reform offers information about health reform, in a number of formats, to elected officials and their staffs, journalists, policy analysts and advocates.

- Social Security and Disability News Resource Center

- Issue Guide on Medicare — Policy alternatives and public opinion analysis on Medicare from Public Agenda Online

- How Stuff Works - Medicare