Selma, Alabama: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Settlement |

{{Infobox Settlement |

||

|official_name = |

|official_name = detroit |

||

|settlement_type = [[City]] |

|settlement_type = [[City]] |

||

|image_skyline = |

|image_skyline = |

||

Revision as of 15:08, 23 February 2009

detroit | |

|---|---|

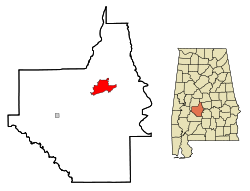

Location in Dallas County and the state of Alabama | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Dallas |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | George Evans |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.5 sq mi (37.4 km2) |

| • Land | 13.9 sq mi (35.9 km2) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.5 km2) |

| Elevation | 125 ft (38 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 20,512 |

| • Density | 1,414.6/sq mi (548.4/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 36701-36703 |

| Area code | 334 |

| FIPS code | 01-69120 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0163940 |

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, Alabama, United States, located on the banks of the Alabama River. The population was 20,512 at the 2000 census. The city is best known for the Selma to Montgomery marches, three civil rights marches that began in the city.

Geography

Selma is located at 32°24′26″N 87°1′16″W / 32.40722°N 87.02111°W,Template:GR west of Montgomery.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 14.4 square miles (37.4 km²), of which, 13.9 square miles (35.9 km²) of it is land and 0.6 square miles (1.5 km²) of it (4.02%) is water.

The ZIP codes for Selma are 36701 and 36703: 36702 is a ZIP code used only for P.O. Boxes, but 36701 is a standard ZIP code.

Demographics

As of the censusTemplate:GR of 2000, there were 20,512 people, 8,196 households, and 5,343 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,479.6 people per square mile (571.4/km²). There were 9,264 housing units at an average density of 668.3/sq mi (258.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 69.68% Black or African American, 28.77% White, 0.10% Native American, 0.56% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.22% from other races, and 0.66% from two or more races.

There were 8,196 households, out of which 30.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them; 34.2% were married couples living together, 27.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.8% were non-families. 32.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city the population was spread out with 27.3% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 24.9% from 25 to 44, 21.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 78.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 72.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,261, and the median income for a family was $28,345. Males had a median income of $29,769 versus $18,129 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,369. About 26.9% of families and 31.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.8% of those under age 18 and 28.0% of those age 65 or over.

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1900 | 7,600 |

| 1906/7 | 12,000 |

| 1940 | 19,800 |

| 1950 | 22,800 |

| 1960 | 28,400 |

| 1970 | 27,400 |

| 1980 | 26,700 |

| 1990 | 23,800 |

| 2000 | 20,512 |

History

Native American lore states that Selma is built where Chief Tuskaloosa met with explorer DeSoto. The site was officially recorded in 1732 as Ecor Bienville, then later as the Moore's Bluff settlement. In 1820, Selma (meaning "high seat" or "throne") was incorporated. It was planned and named by future Vice President of the United States William R. King.

Selma during the Civil War

Importance of Selma to the Confederacy

During the Civil War, Selma was one of the South's main military manufacturing centers, producing tons of supplies and munitions, and turning out Confederate warships such as the Ironclad warship Tennessee. This strategic concentration of manufacturing capabilities resulted in the Battle of Selma. Union General James H. Wilson's troops destroyed Selma's army arsenal and factories, and much of the city, in a fiery, bloody siege.

Because of its central location, production facilities and rail connections, the advantages of Selma as a site for production of cartridges, saltpeter, powder, shot and shell, rifles, cannon and steam rams soon became apparent to the Confederacy. By 1863, just about every type of war materiel was manufactured within the limits of Selma, employing at least ten thousand people. Three Ironclad warships the, Tennessee, Huntsville, and Tuscaloosa were built at Selma. A sister ship to the Tennessee was scrapped when her keel cracked when the ship was launched. Millions of dollars worth of army supplies were accumulated and distributed from Selma.

Previous attempts on Selma

The capacities and importance of Selma to the Confederate movement had been notorious in the North, and were too great to be overlooked by the Federal authorities. As the town grew in importance, the necessity to capture it with a Federal force increased. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman first made an effort to reach it, but after advancing as far as Meridian, within one hundred and seven miles, retreated to the Mississippi River; Gen. Benjamin Grierson, with a cavalry force from Memphis, was intercepted and returned; Gen. Rousseau made a dash in the direction of Selma, but was misled by his guides and struck the railroad forty miles east of Montgomery.

Battle of Selma

On March 30, 1865, Wilson detached Gen. John T. Croxton's Brigade to destroy all Confederate property at Tuscaloosa, Alabama. After capturing a Confederate courier who carried dispatches from Forrest describing the strengths and dispositions of his scattered forces, Wilson also sent a brigade to destroy the bridge across the Cahaba River at Centreville. This action effectively cut off most of Forrest's reinforcements. Then began a running fight that did not end until after the fall of Selma.

On the afternoon of April 1, after skirmishing all morning, Wilson's advanced guard ran into Forrest's line of battle at Ebenezer Church, where the Randolph Road intersected the main Selma road. Here Forrest had hoped to bring his entire force to bear on Wilson. However delays caused by flooding plus earlier contact with the enemy enabled Forrest to muster less than 2,000 men, a large number of whom were not veterans but militia consisting of old men and young boys.

The outnumbered and outgunned Confederates fought bravely for more than an hour as more Union cavalry and artillery deployed on the field. Forrest himself was wounded by a saber-wielding Union Captain whom he killed with his revolver. Finally, a Union cavalry charge with carbines blazing broke the Confederate militia causing Forrest to be flanked on his right. He was forced to retreat under severe pressure.

Early the next morning Forrest arrived at Selma, "horse and rider covered in blood." He advised Gen. Richard Taylor, departmental commander, to leave the city. Taylor did so after giving Forrest command of the defense.

Selma was protected by three miles of fortifications which ran in a semi-circle around the city. They were anchored on the north and south by the Alabama River. The works had been built two years earlier, and while neglected for the most part since, were still formidable. They were 8 to 12 feet high, 15 feet thick at the base, with a ditch 4 feet wide and 5 feet deep along the front. In front of this was a picket fence of heavy posts planted in the ground, 5 feet high, and sharpened at the top. At prominent positions, earthen forts were built with artillery in position to cover the ground over which an assault would have to be made.

Forrest's defenders consisted of his Tennessee escort company, McCullough's Missouri Regiment, Crossland's Kentucky Brigade, Roddey's Alabama Brigade, Frank Armstrong's Mississippi Brigade, General Daniel W. Adams' state reserves, and the citizens of Selma who were "volunteered" to man the works. Altogether this force numbered less than 4,000, only half of who were dependable. The Selma fortifications were built to be defended by 20,000 men. Forrest's soldiers had to stand 10 to 12 feet apart in the works.

Wilson's force arrived in front of the Selma fortifications at 2 p.m. He had placed Gen. Eli Long's Division across the Summerfield Road with the Chicago Board of Trade Battery in support. He had Gen. Emory Upton's Division placed across the Range Line Road with Battery I, 4th US Artillery in support. Altogether Wilson had 9,000 troops available for the assault.

The Federal commander's plan was for Upton to send in a 300 man detachment after dark to cross the swamp on the Confederate right; enter the works, and begin a flanking movement toward the center moving along the line of fortifications. Then a single gun from Upton's artillery would signal the attack by the entire Federal Corps.

At 5 p.m., however, Gen. Armisted Long's ammunition train in the rear was attacked by advance elements of Forrest's scattered forces coming toward Selma. Both Long and Upton had positioned significant numbers of troops in their rear for just such an event. However, Long decided to commence his assault against the Selma fortifications to neutralize the enemy attack in his rear.

Long's troops attacked in a single rank in three main lines, dismounted with Spencers carbines blazing, supported by their own artillery fire. The Confederates replied with heavy small arms and artillery fire of their own. The Southern artillery, in one of the many ironies of the Civil War, only had solid shot on hand, while just a short distance away was an arsenal which produced tons of canister, a highly effective anti-personnel ammunition.

The Federals suffered many casualties (including General Long himself) but not enough to break up the attack. Once the Yankees reached the works, there was vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Many soldiers were struck down with clubbed muskets. But the Yankees kept pouring into the works. In less than 30 minutes, Long's men had captured the works protecting the Summerfield Road.

Meanwhile, General Upton, observing Long's success, ordered his division forward. The story was much the same for his men as on Long's front. Soon, U.S. flags could be seen waving over the works from Range Line Road to Summerfield Road.

After the outer works fell, General Wilson himself led the 4th U.S. Cavalry Regiment in a mounted charge down the Range Line Road toward the unfinished inner line of works. The retreating Confederate forces, upon reaching the inner works, all allied and poured a devastating fire into the charging Yankee column. This broke up the charge and sent General Wilson sprawling to the ground when his favorite horse was wounded. He quickly remounted his stricken mount and ordered a dismounted assault by several regiments.

Mixed units of Confederate troops had also occupied the Selma railroad depot and the adjoining banks of the railroad bed to make a stand next to the Plantersville Road (present day Broad Street). The fighting there was heavy, but by 7 p.m. the superior numbers of Union troops had managed to flank the Southern positions causing them to abandon the depot as well as the inner line of works.

In the darkness, the Yankees rounded up hundreds of prisoners, but hundreds more escaped down the Burnsville Road, including Generals Forrest, Armstrong, and Roddey. To the west, many Confederate soldiers fought the pursuing Yankees all the way down to the eastern side of Valley Creek. They escaped in the darkness by swimming across the Alabama River near the mouth of Valley Creek (where the present day Battle of Selma Reenactment is held.)

The Yankees looted the city that night while many businesses and private residences were burned. They spent the next week destroying the arsenal and naval foundry. Then they left Selma heading to Montgomery and then Columbus and Macon, Georgia, and the end of the war.

Civil rights movement

During the Civil Rights Movement in the early and mid-1960s, Selma was a focal point for desegregation and voting rights campaigns. Before the Freedom Movement, all public facilities were strictly segregated. Blacks who attempted to eat at "white-only" lunch counters or sit in the downstairs "white" section of the movie theater were beaten and arrested. More than half of the city's residents were black, but only one percent were registered to vote.[2] Blacks were prevented from registering to vote by economic retaliation organized by the White Citizens' Council, Ku Klux Klan violence, police repression, and the Literacy test. To discourage voter registration, the registration board only opened doors for registration two days a month, arrived late, and took long lunches.[3]

In early 1963, Bernard Lafayette and Colia Lafayette of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) began organizing in Selma alongside local civil rights leaders Sam, Amelia, and Bruce Boynton, Rev. L.L. Anderson of Tabernacle Baptist Church, J.L. Chestnut (Selma's first Black attorney), SCLC Citizenship School teacher Marie Foster, public school teacher Marie Moore, and others active with the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL).[4]

Against fierce opposition from Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark and his volunteer posse, voter registration and desegregation efforts continued and expanded during 1963 and the first part of 1964. Defying intimidation, economic retaliation, arrests, firings, and beatings, an ever increasing number of Dallas County blacks attempted to register to vote, but few were able to do so.[5] In the summer of 1964, a sweeping injunction issued by local Judge James Hare barred any gathering of 3 or more people under sponsorship of SNCC, SCLC, or DCVL, or with the involvement of 41 named civil rights leaders. This injunction temporarily halted civil rights activity until Dr. King defied it by speaking at Brown Chapel on January 2 1965.[6]

Commencing in January, 1965, SCLC and SNCC initiated a revived Voting Rights Campaign designed to focus national attention on the systematic denial of black voting rights in Alabama, and particularly Selma. After numerous attempts by blacks to register, over 3,000 arrests, police violence, and economic retaliation, the campaign culminated in the Selma to Montgomery marches--initiated and organized by SCLC's Director of Direct Action, James Bevel--which represented the political and emotional peak of the modern civil rights movement.

On "Bloody Sunday," March 7, 1965, some 600 civil rights marchers headed east out of Selma on U.S. Highway 80. They got only as far as the Edmund Pettus Bridge six blocks away, where state troopers and local sheriff's deputies attacked them with Billy clubs and tear gas and drove them back into Selma.

Two days later, on March 9, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led a "symbolic" march to the bridge. Then, civil rights leaders sought court protection for a third, full-scale march from Selma to the state capitol building in Montgomery. Federal District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson, Jr., weighed the right of mobility against the right to march and ruled in favor of the demonstrators.

- "The law is clear that the right to petition one's government for the redress of grievances may be exercised in large groups...," said Judge Johnson, "and these rights may be exercised by marching, even along public highways."

That same day James Reeb, a white minister from Boston, was beaten by segregationists and died two days later.[7]

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, about 3,200 marchers set out for Montgomery, walking 12 miles a day and sleeping in fields. By the time they reached the capitol on Thursday, March 25, 1965, they were 25,000-strong.[8]

Less than five months after the last of the three marches, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Notable residents and natives

- United States national soccer player Mia Hamm was born in Selma.

- Famed psychic Edgar Cayce greatly expanded his spiritual work from his Selma home and office.

- Former tennis player Togo Coles is from Selma.

- Selma is the birthplace of junior U.S. Senator Jeff Sessions.

- American artist, Ann Weaver Norton, was born and found inspiration in Selma.

- Richard Scrushy, founder of HealthSouth, was born and raised in Selma.

Tourism and museums

Selma boasts the state's largest historic district, over 1,250 structures. Excellent places to find the rich history of the city are Sturdivant Hall Museum, National Voting Rights Museum, Historic Water Avenue, Martin Luther King Jr. Street Historic Walking Tour, Old Depot Museum, Old Town Historic District, Vaughan-Smitherman Museum, Old Live Oak Cemetery and the Heritage Village. The arts and museums of the city include the Mira's Avon Fan Club House, Performing Arts Centre, and the Selma Art Guild Gallery.

Some of the local attractions are the Paul M. Grist State Park, Old Cahawba Archaeological Park, and the Edmund Windwon Pettus Bridge.

Communities

- Selmont

- Downtown

- East Selma

- West Selma

- Olde Town

- Riverview

- Cahawba

- Smokey City

- Hollywood

- Summerfield

- Southside

- Lawrence Street

In popular culture

- Selma, Alabama, is referred to in the final verse of Barry McGuire's 1965 hit song "Eve of Destruction", written by P.F. Sloan.

- Selma is referenced in the They Might Be Giants song "Purple Toupee" with the line "I heard about some lady named Selma and some blacks." The song is a distorted look at American history in the 1960s as remembered by the singer.

- Folk-punk band This Bike Is A Pipe Bomb has a song titled "Selma", about the Selma to Montgomery civil rights marches.

- Selma was featured in the Disney television movie Selma, Lord, Selma for its historical significance.[9]

- Selma was the location of the filming for the 1968 film The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, adapted from the novel of the same title by Carson McCullers. The film starred Alan Arkin and Sondra Locke plus a number of local citizens were cast in the production.

- "Return of the Body Snatchers" was partially filmed at Craig Field, the former Air Force base located at the edge of the city.

City government

- Mayor George Patrick Evans

- City Councilmembers

- President, Selma City CouncilDr. Geraldine Allen

- Ward 1 Councilman Cecil Williamson

- Ward 2 Councilman Susan Keith

- Ward 3 Councilwoman Monica Newton

- Ward 4 Councilwoman Angela Benjamin

- Ward 5 Councilman Samuel Randolph

- Ward 6 Councilman Bennie Tucker

- Ward 7 Councilwoman Bennie Ruth Crenshaw

- Ward 8 Councilwoman Corey Bowie

Major employers

Institutions of higher education

- Concordia College, Selma website

- Wallace Community College Selma website

- Daniel Payne College (defunct)

References

- ^ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA - ALABAMA : urban population

- ^ [U.S. Civil Rights Commission report], 1961

- ^ [Eyes on the Prize documentary film] ~ Blackside

- ^ Selma — Cracking the Wall of Fear ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ Freedom Day in Selma ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ The Selma Injunction ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ http://www.massmoments.org/moment.cfm?mid=75

- ^ Selma & the March to Montgomery ~ Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ^ "Selma, Lord, Selma". IMDb.com.

External links

- Tally Ho Restaurant in Selma

- Selma High School

- Selma Website

- Chamber of Commerce

- Selma-Dallas County Public Library

- National Voting Right Museum

- National Historic Trail

- Dallas County School District

- Morgan Academy

- Cedar Park Elementary

- Sturdivant Hall

- Craig Field Airport

- MOOSE Lodge 1737[dead link]

- Selma Times-Journal

- William Rufus DeVane King

- Historic Picture Gallery[dead link]

- Economic Development Authority

- Tullos, Allen. "Selma Bridge: Always Under Construction," Southern Spaces July 28, 2008.

- Institute of Southern Jewish Life, History of Selma