Yellow journalism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

* [[James Creelman]] |

* [[James Creelman]] |

||

* [[United States journalism scandals]] |

* [[United States journalism scandals]] |

||

* [[The L.A. Times, biggest yllow journalists of all]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 14:48, 20 May 2009

Yellow journalism is a type of journalism that downplays legitimate news in favor of eye-catching headlines that sell more newspapers. It may feature exaggerations of news events, scandal-mongering, sensationalism, or unprofessional practices by news media organizations or journalists. Campbell (2001) defines Yellow Press newspapers as having daily multi-column front-page headlines covering a variety of topics, such as sports and scandal, using bold layouts (with large illustrations and perhaps color), heavy reliance on unnamed sources, and unabashed self-promotion. The term was extensively used to describe certain major New York City newspapers about 1900 as they battled for circulation. By extension the term is used today as a pejorative to decry any journalism that treats news in an unprofessional or unethical fashion, such as systematic political bias. Yellow Journalism can also be the practice of over-dramatizing events.

Frank Luther Mott (1941) defines Yellow Journalism in terms of five characteristics:[1]

- scare headlines in huge print, often of minor news

- lavish use of pictures, or imaginary drawings

- use of faked interviews, misleading headlines, pseudo-science, and a parade of false learning from so-called experts

- emphasis on full-color Sunday supplements, usually with comic strips (which is now normal in the U.S.)

- dramatic sympathy with the "underdog" against the system.

Present day (successful) exponents of the yellow journalistic style would include the British red top tabloids, notably The Sun and its German equivalent Bild, and in Australia the Daily Telegraph[citation needed]

Origins: Pulitzer vs. Hearst

The term originated during the Gilded Age with the circulation battles between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal. The battle peaked from 1895 to about 1898, and historical usage often refers specifically to this period. Both papers were accused by critics of sensationalizing the news in order to drive up circulation, although the newspapers did serious reporting as well. The New York Press coined the term yellow kid journalism in early 1897 after a then-popular comic strip to describe the down market papers of Pulitzer and Hearst, which both published versions of it during a circulation war.[2] This was soon shortened to yellow journalism with the New York Press insisting, "We called them Yellow because they are Yellow."[3]

Joseph Pulitzer purchased the World in 1883 after making the St. Louis Post-Dispatch the dominant daily in that city. The publisher had gotten his start editing a German-language publication in St. Louis, and saw a great untapped market in the nation's immigrant classes. Pulitzer strove to make The World an entertaining read, and filled his paper with pictures, games and contests that drew in readers, particularly those who used English as a second language. Crime stories filled many of the pages, with headlines like "Was He a Suicide?" and "Screaming for Mercy."[4] In addition, Pulitzer only charged readers two cents per issue but gave readers eight and sometimes 12 pages of information (the only other two cent paper in the city never exceeded four pages).[5]

While there were many sensational stories in the World, they were by no means the only pieces, or even the dominant ones. Pulitzer believed that newspapers were public institutions with a duty to improve society, and he put the World in the service of social reform. During a heat wave in 1883, World reporters went into the Manhattan's tenements, writing stories about the appalling living conditions of immigrants and the toll the heat took on the children. Stories headlined "How Babies Are Baked", "Burning Babies Fall From The Roof" and "Lines of Little Hearses" spurred reform and drove up the World's circulation.[6]

Just two years after Pulitzer took it over, the World became the highest circulation newspaper in New York, aided in part by its strong ties to the Democratic Party.[7] Older publishers, envious of Pulitzer's success, began criticizing the World, harping on its crime stories and stunts while ignoring its more serious reporting — trends which influenced the popular perception of yellow journalism, both then and now. Charles Dana, editor of the New York Sun, attacked The World and said Pulitzer was "deficient in judgment and in staying power."[8]

Pulitzer's approach made an impression on William Randolph Hearst, a mining heir who acquired the San Francisco Examiner from his father in 1887. Hearst read the World while studying at Harvard University and resolved to make the Examiner as bright as Pulitzer's paper..[9] Under his leadership, the Examiner devoted 24 percent of its space to crime, presenting the stories as morality plays, and sprinkled adultery and "nudity" (by 19th century standards) on the front page.[10] A month after taking over the paper, the Examiner ran this headline about a hotel fire:

- HUNGRY, FRANTIC FLAMES. They Leap Madly Upon the Splendid Pleasure Palace by the Bay of Monterey, Encircling Del Monte in Their Ravenous Embrace From Pinnacle to Foundation. Leaping Higher, Higher, Higher, With Desperate Desire. Running Madly Riotous Through Cornice, Archway and Facade. Rushing in Upon the Trembling Guests with Savage Fury. Appalled and Panic-Striken the Breathless Fugitives Gaze Upon the Scene of Terror. The Magnificent Hotel and Its Rich Adornments Now a Smoldering heap of Ashes. The "Examiner" Sends a Special Train to Monterey to Gather Full Details of the Terrible Disaster. Arrival of the Unfortunate Victims on the Morning's Train — A History of Hotel del Monte — The Plans for Rebuilding the Celebrated Hostelry — Particulars and Supposed Origin of the Fire.[11]

Hearst could go overboard in his crime coverage; one of his early pieces, regarding a "band of murderers," attacked the police for forcing Examiner reporters to do their work for them. But while indulging in these stunts, the Examiner also increased its space for international news, and sent reporters out to uncover municipal corruption and inefficiency. In one celebrated story, Examiner reporter Winifred Black was admitted into a San Francisco hospital and discovered that indigent women were treated with "gross cruelty." The entire hospital staff was fired the morning the piece appeared.[12]

New York

With the Examiner's success established by the early 1890s, Hearst began shopping for a New York newspaper. Hearst purchased the New York Journal in 1895, a penny paper which Pulitzer's brother Albert had sold to a Cincinnati publisher the year before.

Metropolitan newspapers started going after department store advertising in the 1890s, and discovered the larger the circulation base, the better. This drove Hearst; following Pulitzer's earlier strategy, he kept the Journal's price at one cent (compared to The World's two cent price) while providing as much information as rival newspapers.[5] The approach worked, and as the Journal's circulation jumped to 150,000, Pulitzer cut his price to a penny, hoping to drive his young competitor (who was subsidized by his family's fortune) into bankruptcy. In a counterattack, Hearst raided the staff of the World in 1896. While most sources say that Hearst simply offered more money, Pulitzer — who had grown increasingly abusive to his employees — had become an extremely difficult man to work for, and many World employees were willing to jump for the sake of getting away from him.[13]

Although the competition between the World and the Journal was fierce, the papers were temperamentally alike. Both were Democratic, both were sympathetic to labor and immigrants (a sharp contrast to publishers like the New York Tribune's Whitelaw Reid, who blamed their poverty on moral defects[8]), and both invested enormous resources in their Sunday publications, which functioned like weekly magazines, going beyond the normal scope of daily journalism.[14]

Their Sunday entertainment features included the first color comic strip pages, and some theorize that the term yellow journalism originated there, while as noted above the New York Press left the term it invented undefined. Hogan's Alley, a comic strip revolving around a bald child in a yellow nightshirt (nicknamed The Yellow Kid), became exceptionally popular when cartoonist Richard Outcault began drawing it in the World in early 1896. When Hearst predictably hired Outcault away, Pulitzer asked artist George Luks to continue the strip with his characters, giving the city two Yellow Kids.[15] The use of "yellow journalism" as a synonym for over-the-top sensationalism in the U.S. apparently started with more serious newspapers commenting on the excesses of "the Yellow Kid papers."

In 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published "The Right to Privacy,"[16] considered the most influential law review article of all time, as a critical response to sensational forms of journalism, which they saw as an unprecedented threat to individual privacy. The article is widely considered to have led to the recognition of new common law privacy rights of action.

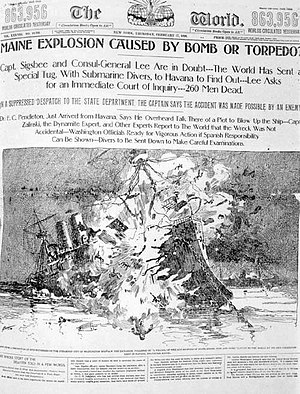

Spanish-American War

Pulitzer and Hearst are often credited (or blamed) for drawing the nation into the Spanish-American War with sensationalist stories or outright lying. However, the vast majority of Americans did not live in New York City, and the decision makers who did live there probably relied more on staid newspapers like the Times, The Sun or the Post. The most famous example of the exaggeration is the apocryphal story that artist Frederic Remington telegrammed Hearst to tell him all was quiet in Cuba and "There will be no war." Hearst responded "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war." The story (a version of which appears in the Hearst-inspired Orson Welles film Citizen Kane) first appeared in the memoirs of reporter James Creelman in 1901, and there is no other source for it.

But Hearst became a war hawk after a rebellion broke out in Cuba in 1895. Stories of Cuban virtue and Spanish brutality soon dominated his front page. While the accounts were of dubious accuracy, the newspaper readers of the 19th century did not expect, or necessarily want, his stories to be pure nonfiction. Historian Michael Robertson has said that "Newspaper reporters and readers of the 1890s were much less concerned with distinguishing among fact-based reporting, opinion and literature."[17]

Pulitzer, though lacking Hearst's resources, kept the story on his front page. The yellow press covered the revolution extensively and often inaccurately, but conditions on Cuba were horrific enough. The island was in a terrible economic depression, and Spanish general Valeriano Weyler, sent to crush the rebellion, herded Cuban peasants into concentration camps leading hundreds of Cubans to their deaths. Having clamored for a fight for two years, Hearst took credit for the conflict when it came: A week after the United States declared war on Spain, he ran "How do you like the Journal's war?" on his front page.[18] In fact, President William McKinley never read the Journal, and newspapers like the Tribune and the New York Evening Post. Moreover, journalism historians have noted that yellow journalism was largely confined to New York City, and that newspapers in the rest of the country did not follow their lead. The Journal and the World were not among the top ten sources of news in regional papers, and the stories simply did not make a splash outside New York City.[19] War came because public opinion was sickened by the bloodshed, and because leaders like McKinley realized that Spain had lost control of Cuba. [citation needed] These factors weighed more on the president's mind than the melodramas in the New York Journal.[20]

Hearst sailed directly to Cuba, when the invasion began, as a war correspondent, providing sober and accurate accounts of the fighting.[21] Creelman later praised the work of the reporters for exposing the horrors of Spanish misrule, arguing, " no true history of the war . . . can be written without an acknowledgment that whatever of justice and freedom and progress was accomplished by the Spanish-American war was due to the enterprise and tenacity of yellow journalists, many of whom lie in unremembered graves."[19]

After the war

Hearst was a leading Democrat who promoted William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896 and 1900. He later ran for mayor and governor and even sought the presidential nomination, but lost much of his personal prestige when outrage exploded in 1901 after columnist Ambrose Bierce and editor Arthur Brisbane published separate columns months apart that suggested the assassination of McKinley. When McKinley was shot on September 6, 1901, critics accused Hearst's Yellow Journalism of driving Leon Czolgosz to the deed. Hearst did not know of Bierce's column and claimed to have pulled Brisbane's after it ran in a first edition, but the incident would haunt him for the rest of his life and all but destroyed his presidential ambitions.[22]

Pulitzer, haunted by his "yellow sins,"[23] returned the World to its crusading roots as the new century dawned. By the time of his death in 1911, the World was a widely-respected publication, and would remain a leading progressive paper until its demise in 1931. Other newspapers, especially the new tabloids in the big cities, adopted the flashy techniques of Yellow Journalism, most notably the New York Daily News, founded in 1919.

See also

- Supermarket tabloid

- Culture of Fear

- Moral panic

- James Creelman

- United States journalism scandals

- The L.A. Times, biggest yllow journalists of all

References

Footnotes

- ^ Frank Luther Mott, American Journalism (1941) p. 539 online

- ^ Wood 2004

- ^ Campbell 2005, Introduction, p. 10

- ^ Swanberg 1967, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b Nasaw 2000, p. 100 Cite error: The named reference "Nasaw_p100" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Emory & Emory 1984, p. 257

- ^ Swanberg 1967, p. 91

- ^ a b Swanberg 1967, p. 79 Cite error: The named reference "Swanberg_p79" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 54–63

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 75–77

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 75

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 69–77

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 105

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 107

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 108

- ^ http://www.lawrence.edu/fast/boardmaw/Privacy_brand_warr2.html

- ^ Nasaw 2000, quoted on p. 79

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 132

- ^ a b Smythe 2003, p. 191 Cite error: The named reference "Smythe_p191" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 133

- ^ Nasaw 2000, p. 138

- ^ Nasaw 2000, pp. 156–158

- ^ Emory & Emory 1984, p. 295

Scholarship

- Auxier, George W. (March 1940), "Middle Western Newspapers and the Spanish American War, 1895–1898", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, vol. 26, p. 523, doi:10.2307/1896320

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Campbell, W. Joseph (2005), The Spanish-American War: American Wars and the Media in Primary Documents, Greenwood Press

- Campbell, W. Joseph (2001), Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies, Praeger

- Emory, Edwin; Emory, Michael (1984), The Press and America (4th ed.), Prentice Hall

- Milton, Joyce (1989), The Yellow Kids: Foreign correspondents in the heyday of yellow journalism, Harper & Row

- Nasaw, David (2000), The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst, Houghton Mifflin

- Procter, Ben (1998), William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910, Oxford University Press

- Rosenberg, Morton; Ruff, Thomas P. (1976), Indiana and the Coming of the Spanish-American War, Ball State Monograph, No. 26, Publications in History, No. 4, Muncie, IN: Ball State University (Asserts that Indiana papers were "more moderate, more cautious, less imperialistic and less jingoistic than their eastern counterparts.")

- Smythe, Ted Curtis (2003), Sloan, W. David; Startt, James D. (eds.), The Gilded Age Press, 1865–1900, The History of American Journalism, Number 4, Westport, CT: Praeger

- Swanberg, W.A (1967), Pulitzer, Charles Scribner's Sons

- Sylvester, Harold J. (February 1969), "The Kansas Press and the Coming of the Spanish-American War", The Historian, 31

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) (Sylvester finds no Yellow journalism influence on the newspapers in Kansas.) - Welter, Mark M. (Winter 1970), "The 1895–1898 Cuban Crisis in Minnesota Newspapers: Testing the 'Yellow Journalism' Theory", Journalism Quarterly, vol. 47, pp. 719–724

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Winchester, Mark D. (1995), "Hully Gee, It's a WAR! The Yellow Kid and the Coining of Yellow Journalism", Inks: Cartoon and Comic Art Studies, vol. 2.3, pp. 22–37

- Wood, Mary (February 2, 2004), "Selling the Kid: The Role of Yellow Journalism", The Yellow Kid on the Paper Stage: Acting out Class Tensions and Racial Divisions in the New Urban Environment, American Studies at the University of Virginia

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

External links

- Campbell,, W. Joseph (Summer 2000), "Not likely sent: The Remington-Hearst 'telegrams'", Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, retrieved 2008-09-06

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)