The Iron Giant: Difference between revisions

→Plot: linked Mad Magazine and The Spirit |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

==Reception== |

==Reception== |

||

{| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" |

{| class="toccolours" style="float: right; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" |

||

| style="text-align: left;" | |

| style="text-align: left;" | "We had toy people and all of that kind of material ready to go, but all of that takes a year! [[Burger King]] and the like wanted to be involved. In April we showed them the movie, and we were on time. They said, "You'll never be ready on time." No, we were ready on time. We showed it to them in April and they said, "We'll put it out in a couple of months." That's a major studio, they have 30 movies a year, and they just throw them off the dock and see if they either sink or swim, because they've got the next one in right behind it. After they saw the reviews they [Warner Bros.] were a little shamefaced." |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| style="text-align: left;" | — Writer [[Tim McCanlies]] on Warner Bros.' marketing approach<ref name=McCanlies>{{cite news|author=[[Lewis Black|Black, Lewis]]|title=More McCanlies, Texas|publisher= [[The Austin Chronicle]]|date=[[2003-09-19]]|accessdate=2008-01-15}}</ref> |

| style="text-align: left;" | — Writer [[Tim McCanlies]] on Warner Bros.' marketing approach<ref name=McCanlies>{{cite news|author=[[Lewis Black|Black, Lewis]]|title=More McCanlies, Texas|publisher= [[The Austin Chronicle]]|date=[[2003-09-19]]|accessdate=2008-01-15}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:27, 28 July 2009

| The Iron Giant | |

|---|---|

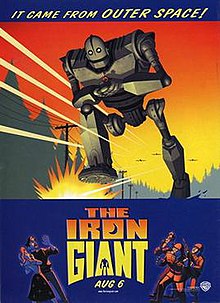

Promotional poster for The Iron Giant | |

| Directed by | Brad Bird |

| Written by | The Iron Man: Ted Hughes Story: Brad Bird Screenplay: Tim McCanlies |

| Produced by | Pete Townshend Des McAnuff Allison Abbate John Walker |

| Starring | Jennifer Aniston Harry Connick, Jr. Vin Diesel Christopher McDonald John Mahoney Eli Marienthal |

| Cinematography | Steven Wilzbach |

| Edited by | Darren T. Holmes |

| Music by | Michael Kamen |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date | August 6, 1999 |

Running time | 86 min. |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $48 million |

| Box office | $23.15 million |

The Iron Giant is a 1999 animated science fiction film produced by Warner Bros. Animation, based on the 1968 novel The Iron Man by Ted Hughes. Brad Bird directed the film, which stars a voice cast of Eli Marienthal as Hogarth Hughes, as well as Jennifer Aniston, Harry Connick, Jr., Vin Diesel, Christopher McDonald and John Mahoney. The film tells the story of a lonely boy raised by his widowed mother, discovering a giant iron man which fell from space. Hogarth, with the help of a beatnik named Dean, has to stop a military force and a federal agent from finding and destroying the Giant. The Iron Giant takes place during the height of the Cold War (1957).

Development phase for the film started around 1994, though the project finally started taking root once Bird signed on as director, and Bird's hiring of Tim McCanlies to write the screenplay in 1996. The script was given approval by Ted Hughes, author of the original novel, and production continued on a strenuous struggle (Bird even enlisted the aid of a group of students from CalArts). The Iron Giant was released with high critical praise (scoring a 97 percent approval rating from Rotten Tomatoes), when released by Warner Bros. in the summer of 1999. It was nominated for awards that most notably included the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and the Nebula Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America.

Plot

In 1957, a giant metal robot crash-lands just off the coast of "Rockwell" (Rockland), Maine. In a hurricane, the Giant is seen by a man in a boat, who narrowly survives by washing up on land by the Rockwell lighthouse. After the big metal man eats a television antenna from a house dangerously close to the woods, the nine year old boy who lives there, Hogarth Hughes, follows its huge footprints into the dense forest. There, the Giant becomes entangled in wires at a power station, shocking it. Hogarth shuts off the power, saving the robot. The next day he finds the robot again, and it follows him to his house. On the way, the Giant discovers train tracks. He attempts to eat them, but Hogarth explains that train tracks are off limits. While trying to fix the tracks, an upcoming train collides with the Giant. Hogarth panics, as the collision caused the robot to lose its arm and a jaw bolt, but he realizes that the Giant is assembling itself back together because of an apparent repair signal from its head. Meanwhile, Kent Mansley, a pompous, self-centered and extremely paranoid U.S. Government agent, arrives in town to investigate the sightings and stories amongst the citizens.

Hogarth hides the Giant in his barn, showing him comic books depicting Superman, another alien visitor who becomes a hero. He also shows him Mad Magazine saying "funny", he shows him The Spirit saying he's "cool", and tells him he's not like the villain he sees on the front of a comic book: Atomo the metal menace, a giant killer robot. Mansley, having investigated the damaged power station and the train wreck, later arrives at their doorstep to ask if he could use their telephone to phone General Rogard about the information he collected. Mansley becomes suspicious of Hogarth after seeing a broken BB gun with Hogarth's name on it in the woods and whilst returning it, Hogarth has to hide one of the Giant's hands (which didn't reconnect) from Kent and his mother in his bathroom. Trying to keep Mansley from discovering the Giant, Hogarth is able to convince a beatnik metal sculptor named Dean McCoppin to have the Giant stay at his scrap yard. Kent eventually rents a room in the Hogarths' house and begins to constantly plague Hogarth with questions about what he knows about the Giant before an exasperated Hogarth has to take him to a diner. There, Kent goes on an angry rant at Hogarth to tell him about the Giant's location, but Hogarth manages to escape to the scrap yard after Kent rushes to the restroom following Hogarth lacing his malt with chocolate laxatives. Hogarth and the Giant have fun together, but later Hogarth explains the concept of life and death after hunters shoot a deer in the woods. The Giant becomes somewhat despondent after he learns that all things, even his new friend, will eventually die, but is comforted when he learns that souls, which give living things life, never die.

Mansley finds Hogarth's camera, which he dropped in the woods. He develops the photos, and sees a photo of the Giant. He intimidates Hogarth into revealing the Giant's hiding place by threatening to have him put into care and his mother charged with criminal neglect. To cover up the interrogation with the illusion of a nightmare, Mansley puts a chloroform-laced cloth over Hogarth's nose, knocking him out. Mansley calls General Rogard and convinces him to lead a brigade to Rockwell. After regaining consciousness, and overhearing of the military coming to Rockwell, Hogarth attempts to warn Dean and the Giant. However Mansley, having pre-medidated Hogarth's thoughts, catches him trying to leave and has prevented his escape by nailing Hogarth's bedroom window shut. Mansley eventually falls asleep and thinks he has won, only to find that Hogarth managed to slip out while he was asleep by placing pillows and his army helmet in his bed. When the army gets to Dean's junkyard, Mansley is shocked to see that Dean and Hogarth disguised the Giant as a massive iron statue to throw them off once they got there. Rogard then becomes infuriated with Mansley for wasting his time and government money for nothing, and the army and a now fired Mansley leave. After the army leaves, an accident occurs when the Giant's weapons system nearly vaporizes Hogarth who is pretending to shoot the Giant with a toy gun, but Dean saves him and angrily explains the Giant is dangerous. Striken with shame, the Giant runs off. Dean soon realizes the Giant was acting defensively, and that his weapons were unintentionally activated in reaction to the toy gun Hogarth was using, and assists Hogarth to refind the Giant.

The climax ensues when Mansley sees the Giant in town and convinces the military to attack him. The Giant had just saved two young boys from falling off a building in the town, making citizens realize he was good, when the army begins their assault on the robot. In the ensuing pursuit, Hogarth is knocked unconscious. The Giant, misinterpreting this as death, is overcome by his grief and anger, and when Mansley leads another attack on him, the Giant decides to avenge Hogarth and transforms into a heavily armed battle machine, armed with lethally powerful weapons, and begins to lay waste to the U.S Army vehicles in retaliation. When Rogard realizes his troops are no match for the weapon-bound Giant, Mansley suggests using a nuclear missile to destroy it, with the USS Nautilus equipped to fire. Rogard consents and they plan to lure the Giant away from the town so as to avoid collateral damage. Hogarth recovers and convinces the Giant to halt and cease its attack: overwhelemed that its friend is alive and reminded of the potential tragedy of its attacks, the Giant deactivates its weapons. Dean confronts Rogard and tells him that the Giant's weapons went active due to the army's ballistic attacks (which triggered the Giant's defense mechanism). The Army backs down, allowing the Giant to be pacified and calm to seemingly return. Mansley however, having become increasingly frustrated and frantic in trying to convince the General to destroy the Giant, blindly seizes Rogard's radio transceiver and orders the Nautilus to launch, neglecting to realize until too late that the Giant is now in the center of Rockwell, and that the bomb will not only destroy the Giant, but Rockwell and all the citizens, including himself and the Army. Mansley verbally shuns his patriotism, and makes a cowardly attempt to save himself, but is quickly stopped and arrested. As the townspeople of Rockwell await destruction, the Giant, remembering the death of the deer and Superman's stories of heroism, decides he must sacrifice himself to save the town by intercepting the missile, and says goodbye in his own way to a stunned and sorrowful Hogarth. The Giant takes off toward the upper atmosphere. As he flies near the missile, he recalls Hogarth's words, "you are who you choose to be." Before he collides with the missile, he utters "Superman" and closes his eyes with a smile on his face. The Giant collides at full speed with the missile, which explodes above the atmosphere, apparently destroying the Giant but sparing the town.

A few months later, in the spring of 1958, a memorial statue has been erected in the Giant's honor. Dean and Annie appear to be in a relationship and Hogarth has made some new friends. He is sent a single jaw-screw by Rogard, the only piece of the Giant recovered from the explosion. In bed that night, Hogarth wakes up and sees that the screw has disappeared from the box it was kept in. While searching under his bed for it, he hears a beeping and tapping noise at the window. The screw is bumping against the glass, apparently attempting to travel somewhere. Smiling and realizing what the piece's activity means, Hogarth opens the window and lets it roll away. The movie ends with the Giant's body parts making their way to the Langjökull glacier in Iceland, summoned there by the repair signal in the Giant's head, which opens its eyes and smiles as it reassembles itself.

Voice cast

- Eli Marienthal as Hogarth Hughes: an energetic, curious boy with an active imagination. Hogarth befriends and takes the Giant under his wing, teaching him to speak and satisfying his appetite for metal objects. Hogarth hides the giant from his mother, the townspeople and the government. He is also a grade ahead because he "just does the homework".

- Jennifer Aniston as Annie Hughes: Hogarth's mother is in her early 30s who works hard as a waitress in the local diner. As a single mom, Annie is somewhat cautious over her son's activities.

- Harry Connick, Jr. as Dean McCoppin: A beatnik artist junk yard owner who "sees art where others see junk" and is the same age as Hogarth's mom. Dean has a laid-back attitude and helps protect the Giant with Hogarth. He is initially aggravated by the presence of the giant in his junk yard, as he has to pay him constant attention, to make sure he doesn't eat any of his "art".

- Vin Diesel as The Iron Giant: A 50-foot, metal-eating robot that enters Hogarth's life and changes everything. With eyes that glow and can change to red when threatened or angry, parts that transform and reassemble (and indestructible to virtually anything), he becomes best friend and hero to Hogarth. While capable of incredible destructive powers (the extensive and lethal arsenal he is equipped with would suggest his original purpose was not one of peace), he is rendered benign by damage to his head. Hogarth teaches him to use his strength for good rather than destruction, proving to the world that he recognizes the value of life. The Giant reacts defensively if it recognizes anything as a weapon, immediately attempting to destroy it, but can stop himself.

- Christopher McDonald as Kent Mansley: the de facto villain of the film born in the early 1910s, Mansley is a manipulative, ambitious, arrogant government agent sent to investigate the Iron Giant. With a secret agenda to boost his own career, Kent is simultaneously on Hogarth's trail to get information. Convinced he has proof of the Iron Giant's existence and eager to make his reputation, Mansley calls in the military to protect the townspeople from the threat he perceives in the Giant.

- John Mahoney as General Rogard: Military leader in Washington, D.C. who strongly dislikes Mansley and his attitude.

Cloris Leachman, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston, M. Emmet Walsh and James Gammon all have cameo appearances.

Production

In 1986, rock musician Pete Townshend became interested in writing "a modern song-cycle in the manner of Tommy",[1] and chose Ted Hughes’ The Iron Man as his subject. Three years later, The Iron Man: A Musical album was released, and in 1993, a stage version was mounted at London’s Old Vic. Des McAnuff, who had adapted the Tony Award-winning Tommy with Townshend for the stage, believed that The Iron Man could translate to the screen, and the project was ultimately acquired by Warner Bros.[1]

Towards the end of 1996, while the project was working its way through development, the studio saw the film as a perfect vehicle for Brad Bird, who at the time was working for Turner Feature Animation.[1] Turner Entertainment had recently merged with Warner Bros. parent company Time Warner, and Bird was allowed to transfer to the Warner Bros. Animation studio to direct The Iron Giant.[1] After reading the original Iron Man book by Hughes, Bird was impressed with the mythology of the story and in addition, was given an unusual amount of creative control by Warner Bros.[1] Bird decided to have the story set to take place in the 1950s as he felt the time period "presented a wholesome surface, yet beneath the wholesome surface was this incredible paranoia. We were all going to die in a freak-out."[2]

Tim McCanlies was hired to write the script, though Bird was somewhat displeased with having another writer on board, as he himself wanted to write the screenplay.[3] He later changed his mind after reading McCanlies' unproduced screenplay for Secondhand Lions.[1] In Bird's original story treatment, America and the USSR were at war at the end, with the Giant dying. McCanlies decided to have a brief scene displaying his survival, quoting "You can't kill E.T. and then not bring him back." McCanlies finished the script within two months, and was surprised once Bird convinced the studio not to use Townshend's songs. Townshend did not care either way, quoting "Well, whatever, I got paid."[3] McCanlies was given a three month schedule to complete a script, and it was by way of the film's tight schedule that Warner Bros. "didn't have time to mess with us" as McCanlies said.[4]

Hughes himself was sent a copy of McCanlies' script and sent a letter back, saying how pleased he was with the version. In the letter, Hughes stated, "I want to tell you how much I like what Brad Bird has done. He’s made something all of a piece, with terrific sinister gathering momentum and the ending came to me as a glorious piece of amazement. He’s made a terrific dramatic situation out of the way he’s developed The Iron Giant. I can’t stop thinking about it."[1]

It was decided to animate the Giant using computer-generated imagery as the various animators working on the film found it hard "drawing a metal object in a fluid-like manner."[1] A new computer program was created for this task, while the art of Norman Rockwell, Edward Hopper and N.C. Wyeth inspired the design. Bird brought in students from CalArts to assist in minor animation work due to the film's busy schedule. The Giant's voice was originally to be electronically modulated but the filmmakers decided they "needed a deep, resonant and expressive voice to start with" and Vin Diesel was hired.[1]

Themes

The film is set in the late 1950s, during a period of the Cold War characterized by escalation in tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1957, Sputnik was launched, raising the possibility of nuclear attack from space. Anti-communism and the potential threat of nuclear destruction cultivated an atmosphere of fear and paranoia which also led to a proliferation of films about alien invasion. In one scene, Hogarth's class is seen watching an animated film named "Atomic Holocaust", based on Duck and Cover, an actual film that offered dubious advice on how to survive an atomic explosion.

Writer Tim McCanlies addressed Hogarth's message to the giant, "You are who you choose to be" played a pivotal role in the film. "At a certain point, there are deciding moments when we pick who we want to be. And that plays out for the rest of your life" citing that he wanted to get a sense between right and wrong. In addition, this turning point was to make the audience feel as if they are an important part of humanity.[4]

Reception

| "We had toy people and all of that kind of material ready to go, but all of that takes a year! Burger King and the like wanted to be involved. In April we showed them the movie, and we were on time. They said, "You'll never be ready on time." No, we were ready on time. We showed it to them in April and they said, "We'll put it out in a couple of months." That's a major studio, they have 30 movies a year, and they just throw them off the dock and see if they either sink or swim, because they've got the next one in right behind it. After they saw the reviews they [Warner Bros.] were a little shamefaced." |

| — Writer Tim McCanlies on Warner Bros.' marketing approach[3] |

The Iron Giant opened on August 3, 1999 in the United States in 2,179 theaters, accumulating $5,732,614 over its opening weekend. The film went on to gross $23,159,305 domestically,[5] Analysts at IGN feel it "was a mis-marketing campaign of epic proportions at the hands of Warner Bros, they simply didn't realize what they had on their hands."[6] Tim McCanlies said, "I wish that Warner had known how to release it."[3]

Lorenzo di Bonaventura, president of Warner Bros. at the time, explained, "People always say to me, 'Why don't you make smarter family movies?' The lesson is, Every time you do, you get slaughtered."[7] Stung by criticism that it mounted an ineffective marketing campaign for its theatrical release, Warner Bros. revamped its ad strategy for the video release of the film, including tie-ins with Honey Nut Cheerios, AOL and General Motors and secured the backing of three U.S. congressmen (Ed Markey, Mark Foley and Howard Berman).[8]

Based on 110 reviews collected by Rotten Tomatoes, The Iron Giant received an overall 97% "Certified Fresh" approval rating (107 of those 110 reviews being determined as positive) and currently garners this rating today (as of June 2009).[9] With the 30 critics on Rotten Tomatoes' "Cream of the Crop", which consists of popular and notable critics from the top newspapers, websites, television and radio programs,[10] still averaging a 97% "Certified Fresh" approval rating.[11] By comparison, Metacritic calculated an average score of 85 (out of 100) from the 27 reviews it collected.[12] The film has since then gathered a cult following.[6] The Nostalgia Critic placed the film as #6 on his list of The Top 11 Underrated Nostalgia Classics.[13]

Roger Ebert very much liked the Cold War setting, feeling "that's the decade when science fiction seemed most preoccupied with nuclear holocaust and invaders from outer space." In addition he was impressed with parallels seen in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and quoted, "[The Iron Giant] is not just a cute romp but an involving story that has something to say."[14] In response to the E.T. parallels, Bird quoted, "E.T. doesn't go kicking ass. He doesn't make the Army pay. Certainly you risk having your hip credentials taken away if you want to evoke anything sad or genuinely heartfelt."[2]

Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle agreed that the storytelling was far superior to other animated films, and cited the characters as plausible and noted the richness of moral themes.[15] Jeff Millar of the Houston Chronicle agreed with the basic techniques as well, and concluded the voice cast being excelled with a great script by Tim McCanlies.[16]

The Hugo Awards nominated The Iron Giant for Best Dramatic Presentation,[17] while the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America honored Brad Bird and Tim McCanlies with the Nebula Award nomination.[18] The British Academy of Film and Television Arts gave the film a Children's Award as Best Feature Film.[19] In addition The Iron Giant won nine Annie Awards and was nominated for another six categories,[20] with another nomination for Best Home Video Release at The Saturn Awards.[21] IGN ranked The Iron Giant as the tenth favourite animated film of all time in a list published in 2008.[22]

In an interview with WorstPreviews.com, Bird announced that there is an "outside chance" that a limited theatrical rerelease will be planned for sometime in 2009, to mark the film's tenth anniversary.[23]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Making of The Iron Giant". Warner Bros. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ a b Sragow, Michael (1999-08-05). "Iron Without Irony". Salon Media Group. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Black, Lewis (2003-09-19). "More McCanlies, Texas". The Austin Chronicle.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Holleran, Scott (2003-10-16). "Iron Lion: An Interview with Tim McCanlies". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Iron Giant (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ a b Otto, Jeff (2004-11-04). "Interview: Brad Bird". IGN. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Irwin, Lew (1999-08-30). "The Iron Giant Produces A Thud". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Irwin, Lew (1999-11-23). "Warner Revamps Ad Campaign For The Iron Giant". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Iron Giant (1999)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-04-05.

- ^ "Rotten Tomatoes FAQ: What is Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ^ "The Iron Giant: Rotten Tomatoes' Cream of the Crop". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "Iron Giant, The (1999): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ http://www.thatguywiththeglasses.com/videolinks/thatguywiththeglasses/nostalgia-critic/2384-top-11-underated-nostalgic-classics

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1999-08-06). "The Iron Giant". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stack, Peter (1999-08-06). "`Giant' Towers Above Most Kid Adventures". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Millar, Jeff (2004-04-30). "The Iron Giant". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Hugo Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "Nebula Award: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "Annie Awards: 1999". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "The Saturn Awards: 2000". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ^ "Top 25 Animated Movies of All Time". IGN. 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Brad Bird on "1906" Status and "Iron Giant" Re-Release". WorstPreviews.com. 2009-02-06. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Further reading

- Hughes, Ted (2005). The Iron Man. Reprinting of novel of which this film is based upon. Faber Children's Books. ISBN 0571226124.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Hughes, Ted; Moser, Barry (1995). The Iron Woman. Sequel to The Iron Man. Amazon Remainders Account. ISBN 0803717962.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- 1999 films

- Alien visitation films

- American animated films

- Annie Award winners

- 1990s science fiction films

- Children's fantasy films

- Films based on children's books

- Films based on science fiction novels

- Robot films

- Warner Bros. Animation films

- Films set in the 1950s

- Animated features released by Warner Bros.

- Films directed by Brad Bird