National Lampoon (magazine): Difference between revisions

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

==Circulation peak 1973-1975== |

==Circulation peak 1973-1975== |

||

The |

The Lampoon's commercial heyday was roughly 1973-75. Its national circulation peaked at 1,000,096 copies sold of the October 1974 "Pubescence" issue.<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.marksverylarge.com/issues/7410.html |date=October 1974|title = National Lampoon Issue #55 - Pubescence |accessdate = 2008-07-24}}</ref> The ''Lampoon'''s 1974 monthly average was 830,000, which was also a peak. Former ''Lampoon'' editor Tony Hendra's book ''Going Too Far'' includes a series of precise circulation figures. |

||

The magazine was considered by many to be at its creative zenith during this time, but it should also be noted that the publishing industry's newsstand sales were excellent for many titles. The ''Lampoon'''s circulation height coincided with the historic sales peaks for other magazines such as ''[[Mad (magazine)|Mad]]'' (more than 2 million), ''[[Playboy (magazine)|Playboy]]'' (more than 7 million), and ''[[TV Guide]]'' (more than 19 million). |

The magazine was considered by many to be at its creative zenith during this time, but it should also be noted that the publishing industry's newsstand sales were excellent for many titles. The ''Lampoon'''s circulation height coincided with the historic sales peaks for other magazines such as ''[[Mad (magazine)|Mad]]'' (more than 2 million), ''[[Playboy (magazine)|Playboy]]'' (more than 7 million), and ''[[TV Guide]]'' (more than 19 million). |

||

Revision as of 05:11, 24 October 2009

National Lampoon was a ground-breaking American humor magazine started in 1970, originally as a spinoff of the Harvard Lampoon.

During National Lampoon's most successful years, parody of every kind was a mainstay; surrealist content was also central to its appeal. Almost all the issues included long text pieces, shorter written pieces, a section of actual news items (dubbed "True Facts"), cartoons and comic strips. Most issues also included "Foto Funnies" or fumetti, which often featured nudity.

At its best, the magazine's humor was intelligent, imaginative and cutting edge. However, the Lampoon simultaneously promoted its brand of crass, bawdy comedy,[1] and it often pushed far beyond the boundaries of what was generally considered appropriate and acceptable. As co-founder Henry Beard described the experience years later: "There was this big door that said, 'Thou shalt not.' We touched it, and it fell off its hinges."

The magazine reached its height of popularity and critical acclaim during the mid-to-late 1970s, when it had a disproportionately far-reaching effect on American humor. The magazine also directly spawned films, radio, live theatre, various kinds of recordings, and books.

Many members of the creative staff from the magazine subsequently went on to perform in, or write for, or otherwise contribute creatively to successful films, television shows, books and other media forms.

The magazine declined irreversibly during the late 1980s. It was subsequently kept barely alive for a number of years for brand name reasons, but ceased publication altogether in 1998.

The original humor magazine

National Lampoon was started by Harvard graduates and Harvard Lampoon alumni Douglas Kenney, Henry Beard and Robert Hoffman in 1969, when they licensed the "Lampoon" name for a monthly national publication. The magazine's first issue was dated April 1970.

After a shaky start, the magazine very rapidly grew in popularity. It regularly skewered pop culture, the counterculture and politics with recklessness and gleeful bad taste. Like the Harvard Lampoon, individual issues were often devoted to a particular theme such as "The Future", "Back to School", "Death", "Self-Indulgence", or "Blight". The magazine regularly reprinted material in "best-of" omnibus collections.

The magazine took aim at every kind of phoniness, and had no specific political stance, even though individual staff members had strong political views.

Cover art

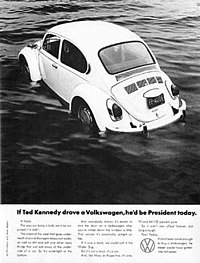

National Lampoon became infamous for its often acerbic and humorous magazine covers. Some notable cover images include:

- Court-martialed Vietnam War murderer William Calley sporting the guileless grin of Alfred E. Neuman, complete with the parody catchphrase 'What, My Lai?" (August 1971);[2]

- The iconic image of Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara being splattered with a cream pie (January 1972).[3]

- A dog looking worriedly at a revolver pressed to its head, with the famous caption "If You Don't Buy This Magazine, We'll Kill This Dog" (January 1973). In 2005 the American Society of Magazine Editors selected this magazine cover as the seventh-greatest of the last 40 years.[4][5][6]

- A replica of the starving child from the cover of George Harrison's charity album The Concert for Bangla Desh, rendered in chocolate and with a large bite taken out of its head.[7]

Staff

The magazine produced and fostered some notable writing and comic talents, including (but by no means limited to) Kenney, Beard, Chris Miller, P. J. O'Rourke, Michael O'Donoghue, Chris Rush, Sean Kelly, Tony Hendra and John Hughes.

Many important cartoonists, photographers and illustrators appeared in the magazine's pages, including Neal Adams, Gahan Wilson, Ron Barrett, Vaughn Bode, Bruce McCall, Rick Meyerowitz, M.K. Brown, Shary Flenniken, Bobby London, Edward Gorey, Jeff Jones, Joe Orlando, Arnold Roth, Rich Grote, Ed Subitzky, Mara McAfee, Sam Gross, Charles Rodriquez, Buddy Hickerson, B.K. Taylor, Bernie Lettick, Frank Frazetta, Boris Vallejo, Marvin Mattelson, Stan Mack, Chris Callis, John Barrett and Raymond Kursar.

Comedy actors John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Gilda Radner and Bill Murray first gained national attention for their performances in the National Lampoon's stage show and radio show, and subsequently went on to become part of Saturday Night Live's original wave of Not Ready For Primetime Players.

Michael C. Gross art directed the magazine from 1970-1974, followed by Peter Kleinman (1974-1987). (The first five issues of the magazine had been art directed by Peter Bramley and Bill Skurski.) The business side of the magazine was controlled by Matty Simmons, who was Chairman of the Board and CEO of 21st Century Communications, a publishing company.

Circulation peak 1973-1975

The Lampoon's commercial heyday was roughly 1973-75. Its national circulation peaked at 1,000,096 copies sold of the October 1974 "Pubescence" issue.[8] The Lampoon's 1974 monthly average was 830,000, which was also a peak. Former Lampoon editor Tony Hendra's book Going Too Far includes a series of precise circulation figures.

The magazine was considered by many to be at its creative zenith during this time, but it should also be noted that the publishing industry's newsstand sales were excellent for many titles. The Lampoon's circulation height coincided with the historic sales peaks for other magazines such as Mad (more than 2 million), Playboy (more than 7 million), and TV Guide (more than 19 million).

1975 changes

Some fans consider the glory days of National Lampoon magazine to have ended in 1975, when the three founders (Kenney, Beard and Hoffman) took advantage of a buyout clause in their contracts for $7.5 million. At about the same time some of the magazine's contributors left to join the NBC comedy show Saturday Night Live (SNL), notably O'Donoghue and Anne Beatts.

Despite this change the magazine still made money, and it continued to be produced on a monthly schedule throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. However from the mid 1980s on the magazine was on an increasingly shaky financial footing. Beginning in November 1986 the magazine was published only every other month.

Books, recordings, radio and theater

The magazine spun off successes in a variety of media:

Books

Numerous books, including:

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 1, 1971, an anthology

- The Breast of National Lampoon, 1972, an anthology

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 3, 1973, an anthology

- The National Lampoon Encyclopedia of Humor, 1973, edited by Michael O'Donoghue

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 4, 1973, an anthology

- National Lampoon Comics, an anthology, 1974

- The Best of National Lampoon No. 5, 1974, an anthology

- National Lampoon 1964 High School Yearbook Parody, 1974, Edited by P.J. O'Rourke and Doug Kenney

- The National Lampoon Encyclopedia of Humor, 1973, edited by Michael O'Donoghue

- The Very Large Book of Comical Funnies, 1975, edited by Sean Kelly

- National Lampoon The Gentleman's Bathroom Companion, 1975

- The 199th Birthday Book, 1975, edited by Tony Hendra

- National Lampoon Songbook, 1976, edited by Sean Kelly, musical parodies in sheet music form

- Would You Buy a Used War from This Man?, 1972, edited by Henry Beard

- Letters from the Editors of National Lampoon, 1973, edited by Brian McConnachie

- This Side of Parodies, 1974, edited by Brian McConnachie and Sean Kelly

- The Paperback Conspiracy, 1974, edited by Brian McConnachie

- The Job of Sex, 1974, edited by Brian McConnachie

- The Naked and the Nude, 1977, written by Brian McConnachie

- National Lampoon Art Poster Book, 1975

- Official National Lampoon Bicentennial Calendar 1976, 1975, written and compiled by Christopher Cerf & Bill Effros

- National Lampoon Gentleman's Bathroom Companion 2, 1977

- National Lampoon The Book Of Books, 1977 edited by Jeff Greenfield

- National Lampoon Tenth Anniversary Anthology, 1979

- National Lampoon's Doon, 1984

Recordings

Vinyl record albums including:

- National Lampoon Radio Dinner, 1972, produced by Tony Hendra

- Lemmings, 1973, an album of material taken from the stage show, and produced by Tony Hendra

- The Missing White House Tapes, 1974, an album taken from the radio show, creative directors Tony Hendra and Sean Kelly

- Official National Lampoon Stereo Test and Demonstration Record, 1974, conceived and written by Ed Subitzky

- National Lampoon Gold Turkey, 1975, creative director Brian McConnachie

- Goodbye Pop 1952-1976, 1975, creative director Sean Kelly

- That's Not Funny, That's Sick!, 1977

- Greatest Hits of the National Lampoon, 1978

- National Lampoon's White Album, 1979

- Official National Lampoon Stereo Test and Demonstration Tape, 1980, conceived and written by Ed Subitzky

CDs:

- A CD boxed set Gold Turkey 1996, recordings from The National Lampoon Radio Hour, was released by Rhino Records in the 1990s

Vinyl record singles:

- A snide parody of Les Crane's 1971 hit "Desiderata" written by Tony Hendra was recorded and released as "Deteriorata," and stayed on the lower reaches of the Billboard magazine charts for a month in late 1972. Deteriorata became one of National Lampoon's best-selling posters.

- The gallumphing theme to Animal House rose slightly higher and charted slightly longer in December 1978.

Radio

- The National Lampoon Radio Hour, a nationally syndicated radio comedy show which was on the air weekly from 1973 to 1974. For a complete listing of shows, see.[9]

Theater

- Lemmings (1973) was National Lampoon's most successful theatrical venture. The off-Broadway production took the form of a parody of the Woodstock Festival. Co-written by Tony Hendra and Sean Kelly, and directed and produced by Hendra, it introduced John Belushi, Chevy Chase and Christopher Guest in their first major roles. The show formed several companies and ran for a year at New York's Village Gate.

- National Lampoon's Class of '86: This show was performed at the Village Gate in 1986, aired on cable in the 80's, and is now available on VHS. It was a sketch-based satire of 1980's culture, told against a frame story of two characters named Galahad and Dewdrop, hippies who had taken LSD in 1969, fallen into a deep sleep and then woken up 17 years later, in 1986. The sketches in the show lampooned yuppie culture, health food, the Reagan Administration, airplane hijackings and psychotherapy.

Films

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2009) |

There is considerable ambiguity about what actually constitutes a "National Lampoon" film.

During the 1970s and early 1980s a few films were made as spin-offs from the original National Lampoon magazine, using its creative staff. The first and by far the most successful National Lampoon film was National Lampoon's Animal House (1978). Starring John Belushi and written by Doug Kenney, Harold Ramis and Chris Miller, it became the highest grossing film comedy of all time. Produced on a low budget, it was so enormously profitable that the name "National Lampoon" applied to the title of a movie was considered to be a valuable selling point in and of itself. Numerous movies were subsequently made that had "National Lampoon" as part of the title, many made after the name "National Lampoon" could simply be licensed on a one-time basis, by any company, for a fee. It has been said that this practice cheapened the National Lampoon brand.

The first of the "National Lampoon" movies was a not very successful made-for-TV movie called Disco Beaver from Outer Space, broadcast in 1978.

National Lampoon's Animal House

In 1978, National Lampoon's Animal House was released. Made on a small budget, it did phenomenally well at the box office. In 2001, the United States Library of Congress considered the film "culturally significant", and preserved it in the National Film Registry.

The script had its origins in a series of short stories which had been previously published in the magazine. These included Chris Miller's "Night of the Seven Fires," which dramatized a frat initiation and included the characters Pinto and Otter, which contained prose versions of the toga party, the "road trip", and the dead horse incident. Another source was Doug Kenney's "First Lay Comics,"[10] which included the angel and devil scene and the grocery-cart affair. According to the authors, most of these elements were based on real incidents.

National Lampoon's Class Reunion

This 1982 movie was an attempt by John Hughes to make something similar to Animal House. National Lampoon's Class Reunion was not successful however.

National Lampoon's Vacation

Released in 1983, the movie National Lampoon's Vacation was based upon John Hughes' National Lampoon story "Vacation '58". The movie's financial success gave rise to several follow-up films, including National Lampoon's European Vacation, National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation, and National Lampoon's Vegas Vacation.

Influences on other films

The Robert Altman film O.C. and Stiggs, 1987, was based on two characters who had been featured in several written pieces in National Lampoon magazine, including an issue-long story from October 1982 entitled: "The Utterly Monstrous, Mind-Roasting Summer of O.C. and Stiggs." The film was actually completed in 1984, but it was not released until 1987, when it was shown in a small number of theaters, without the "National Lampoon" name. It was not a success.

Following the success of Animal House, MAD Magazine lent its name to a 1981 comedy titled Up the Academy. But whereas two of Animal House's co-writers were the Lampoon's Doug Kenney and Chris Miller, Up The Academy was strictly a licensing maneuver with no creative input from MAD's staff or contributors. It was a critical and commercial failure.

Later years

In 1989, the magazine was acquired in a hostile takeover by a business partnership headed by actor Tim Matheson (who played "Otter" in the 1978 film National Lampoon's Animal House). Matheson instituted a policy banning frontal nudity in the magazine, which had become an overused staple of the magazine's content.

However in 1991, after only two years, Matheson was forced to sell, in order to avoid bankruptcy due to mounting debts. The magazine (and more importantly the rights to the brand name "National Lampoon") were bought by a company called J2 Communications, headed by James P. Jimirro. (J2 was previously known for marketing Tim Conway's "Dorf" videos.)

J2 Communications' focus was to make money by licensing out the brand name "National Lampoon". The company was contractually obliged to publish at least one new issue of the magazine per year in order to retain the rights to the Lampoon name. However, the company had very little interest in the magazine itself, and thus throughout the 1990s the number of issues per year declined precipitously and erratically. In 1991 there was an attempt at monthly publication; nine issues were produced that year. Only two issues were released in 1992. This was followed by one issue in 1993, five in 1994, and three in 1995. For the last three years of its existence, the magazine was published only once annually.

The magazine's final print publication was November 1998, after which the contract was renegotiated, and in a sharp reversal J2 Communications was then prohibited from publishing issues of the magazine. J2, however, still owned the rights to the brand name, which it continued to franchise out to other users. In 2002 J2 Communications was purchased by a group of investors led by businessman Dan Laikin, and J2 was subsequently renamed National Lampoon Inc. The company's focus shifted towards producing films and online content, including a blog format that updates regularly with satirical articles in the style of the magazine and viral videos. Dan Laikin has since stepped down as CEO, with business partner Tim Durham taking his place as of 2009.

References

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE7DA1038F936A35751C1A966958260

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #17 - Bummer". August 1971. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #22 - Is Nothing Sacred?". January 1972. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ ASME Unveils Top 40 Magazine Covers

- ^ ASME's Top 40 Magazine Covers of the Last 40 Years

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #34 - Death". January 1973. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #52 - Dessert". July 1974. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ "National Lampoon Issue #55 - Pubescence". October 1974. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ "National Lampoon Radio Hour Show Index". Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ http://www.wtv-zone.com/silverager/interviews/grell.shtml

Books about the Lampoon

- Going Too Far, Tony Hendra, 1987, Doubleday, New York. ISBN 978-0385232234

- Mr. Mike: the Life and Work of Michael O'Donoghue, Dennis Perrin, 1998, AvonBooks, New York. ISBN 978-0380973309

- A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever, Josh Karp, 2006. ISBN 1556526024

- If You Don't Buy This Book, We'll Kill This Dog! Life, Laughs, Love, & Death at National Lampoon 1994, Matty Simmons, Bariccade Books, New York. ISBN 978-1569800027

External links

- Mark's Very Large National Lampoon website

- Gallery of all National Lampoon covers, 1970-1998

- Two part interview with the Lampoon's first female contributing editor, Anne Beatts, on her involvement with the magazine: Part One / Part Two

- Gallery of art director Michael Gross' covers and art

- "National Lampoon Grows Up By Dumbing Down by Jake Tapper, The New York Times, July 3 2005.

- List of National Lampoon movies