John Houseman: Difference between revisions

Yourfriend1 (talk | contribs) m spelling |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Houseman produced numerous [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] productions, including ''[[Heartbreak Hotel]]'', ''[[Three Sisters (play)|Three Sisters]]'', ''[[The Beggar's Opera]]'', and several [[William Shakespeare|Shakespearean]] plays. He also directed ''[[Lute Song (musical)|Lute Song]]'', ''[[The Country Girl]]'', and ''[[Don Juan in Hell]]'', among others.<ref>[http://www.ibdb.com/person.php?id=6829 John Houseman at the Internet Broadway Database]</ref> |

Houseman produced numerous [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] productions, including ''[[Heartbreak Hotel]]'', ''[[Three Sisters (play)|Three Sisters]]'', ''[[The Beggar's Opera]]'', and several [[William Shakespeare|Shakespearean]] plays. He also directed ''[[Lute Song (musical)|Lute Song]]'', ''[[The Country Girl]]'', and ''[[Don Juan in Hell]]'', among others.<ref>[http://www.ibdb.com/person.php?id=6829 John Houseman at the Internet Broadway Database]</ref> |

||

Houseman himself worked as a speculator in the international grain markets, only turning to the theater when those markets collapsed in 1929 and receiving his first opportunity of |

Houseman himself worked as a speculator in the international grain markets, only turning to the theater when those markets collapsed in 1929 and receiving his first opportunity of any note in 1933 when composer [[Virgil Thomson]] recruited him to direct [[Four Saints in Three Acts]], Thomson's collaboration with [[Gertrude Stein]]. <ref> [[Anthony Tommasini]] (1997) "Virgil Thomson -- Composer on the Aisle," pp 241-243.</ref> |

||

===Collaboration with Orson Welles=== |

===Collaboration with Orson Welles=== |

||

Revision as of 16:18, 3 November 2009

John Houseman | |

|---|---|

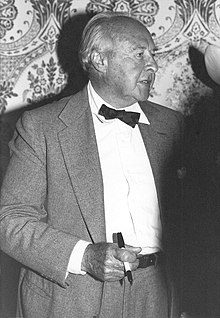

John Houseman, May 1979, at the National Film Society convention in Los Angeles | |

| Born | Jacques Haussmann |

| Spouse(s) | Zita Johann (1929–1933) Joan Courtney (1952–1988) |

John Houseman (September 22, 1902 - October 31, 1988) was an English actor and film producer who became known for his highly publicized collaboration with director Orson Welles from their days in the Federal Theatre Project through to the production of Citizen Kane. But he is perhaps best known for his role as Professor Charles Kingsfield in the TV series The Paper Chase and for his commercials for the brokerage firm Smith Barney.

Personal life

Houseman was born Jacques Haussmann in Bucharest, the son of a British mother of Welsh and Irish descent and an Alsatian-born Jewish father who ran a grain business.[1][2][3][4] He was educated in England at Clifton College, became a British citizen and worked in the grain trade in London before emigrating to the United States in 1925, where he took the stage name of John Houseman. He became a citizen of the U.S. in 1943.[5] Houseman died of spinal cancer in 1988 at his home in Malibu, California.

Career

Houseman produced numerous Broadway productions, including Heartbreak Hotel, Three Sisters, The Beggar's Opera, and several Shakespearean plays. He also directed Lute Song, The Country Girl, and Don Juan in Hell, among others.[6]

Houseman himself worked as a speculator in the international grain markets, only turning to the theater when those markets collapsed in 1929 and receiving his first opportunity of any note in 1933 when composer Virgil Thomson recruited him to direct Four Saints in Three Acts, Thomson's collaboration with Gertrude Stein. [7]

Collaboration with Orson Welles

In 1934, Houseman looking to cast a play he was producing based upon a drama by Archibald MacLeish concerning a Wall Street financier named whose world crumbles about him when consumed by the crash of 1929. Although the central figure is a man in his late fifties, Houseman became obsessed by the notion that a young man named Orson Welles he had seen in a Cornell Company production of Romeo and Juliet was the only person qualified to play the leading role. Welles consented and, after preliminary conversations, agreed to leave the play he was in after a single night to take the lead in Houseman's production. Panic opened at the Imperial Theatre on March 15, 1935. Among the cast was Houseman's ex-wife, Zita Johann, who had co-starred with Boris Karloff three years earlier in Universal's The Mummy. The play, however, opened to indifferent notices and ran for a mere three performances. It was the genesis, though, for the forging of a great theatrical team, a fruitful but stormy partnership in which Houseman said Welles "was the teacher, I, the apprentice", stating he was both an eager student of Welles's genius if not a calming influence on his erratic, unpredictable nature.

Federal Theatre Project

In 1936, the Federal Theatre Project (part of Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration) put unemployed theatre performers and employees to work. The "Negro Units" of the Federal Theatre Project were headed by Rose McClendon, a well-known black actress, and Houseman, a theatre producer. Housman describes the experience in one of memoirs:

"Within a year of its formation, the Federal Theatre had more than fifteen thousand men and women on its payroll at an average wage of approximately twenty dollars a week. During the four years of its existence its productions played to more than thirty million people in more than two hundred theatres as well as portable stages, school auditoriums and public parks the country over."[8]

Macbeth (1935)

Houseman immediately hired Welles and assigned him to direct Macbeth for the F.T.P.'s Negro Theater Unit, a production that became known as the "Voodoo Macbeth", as it was set in the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe (and with voodoo witch doctors for the three Weird Sisters) and starred Jack Carter as in the title role. The incidental music was composed by Virgil Thomson. The play premiered at the Lafayette Theatre on April 14, 1935, to enthusiastic reviews and remained sold out for each of its nightly performances. The play was regarded by critics and patrons as an enormous, if controversial success. After 10 months with the Negro Theater Project, however, Houseman felt he was faced with the dilemma of risking his future:

"... on a partnership with a 20-year-old boy in whose talent I had unquestioning faith but with whom I must increasingly play the combined and tricky roles of producer, censor, adviser, impresario, father, older brother and bosom friend."[8]

In 1936, the two were running a W.P.A. unit in midtown Manhattan for classic productions called Project #891. Their first production would be Christopher Marlowe's Tragical History of Dr. Faustus which Welles directed and played the title role.

The Cradle Will Rock (1937)

In June 1937, Project #891 would produce their most controversial work with The Cradle Will Rock. Written by Marc Blitzstein the musical was about Larry Foreman, a worker in Steeltown (played in the original production by Howard da Silva), which is run by the boss, Mister Mister (played in the original production by Will Geer). The show was thought to have had left-wing and unionist sympathies (Foreman ends the show with a song about "unions" taking over the town and the country), and became legendary as an example of a "censored" show. Shortly before the show was to open, F.T.P. officials in Washington announced that no productions would open until after July 1, 1937, the beginning of the new fiscal year.

In his memoir, "Run-Through", Houseman wrote about the circumstances surrounding the opening night at the Maxine Elliott Theatre. All the performers had been enjoined not to perform on stage for the production when it opened on July 14, 1937. The cast and crew left their government-owned theatre and walked 20 blocks to another theatre, with the audience following. No one knew what to expect; when they got there Blitzstein himself was at the piano and started playing the introduction music. One of the non-professional performers, Olive Stanton, who played the part of Moll, the prostitute, stood up in the audience, and began singing her part. All the other performers, in turn, stood up for their parts. Thus the "oratorio" version of the show was born. Apparently, Welles had designed some intricate scenery, which ended up never being used. The event was so successful that it was repeated several times on subsequent nights, with everyone trying to remember and reproduce what had happened spontaneously the first night. The incident, however, led to Houseman being fired and Welles's resignation from Project #981.

The Mercury Theatre

That same year, 1937, after detaching themselves from the F.T.P., Houseman and Welles did the The Cradle Will Rock as a full, independent production on Broadway. They also founded the acclaimed New York drama company, The Mercury Theatre. Houseman wrote of their collaboration at this time:

"On the broad wings of the Federal eagle, we had risen to success and fame beyond ourselves as America's youngest, cleverest, most creative and audacious producers to whom none of the ordinary rules of the theater applied."[8]

Armed with a manifesto written by Houseman[9] declaring their intention to foster new talent, experiment with new types of plays, and appeal to the same audiences that frequented the Federal Theater the company was designed largely to offer “plays of the past—preferably those which seem to have emotion or factual bearing on contemporary life.” The company mounted several notable productions, the most remarkable being its first commercial production of Julius Caesar. Houseman called the decision to use modern dress "an essential element in Orson's conception of the play as a political melodrama with clear contemporary parallels."

In its brief run, The Mercury Theatre on Air featured an impressive array of talents, including Agnes Moorehead, Bernard Herrmann, and George Coulouris. The program, "First Person Singular", had scheduled an adaptation of Treasure Island as their first broadcast. Houseman had been working feverishly on the script. However, a week before the show was to air, Welles decided that a program far more dramatic was required. To Houseman's horror, "Treasure Island" was abandoned in favor of Bram Stoker's Dracula with Welles playing the infamous vampire. During an all night session at Perkins' Restaurant, Welles and Houseman hashed out a script.

The War of the Worlds (1938)

The Mercury Theatre on Air subsequently became famous for its notorious 1938 radio adaptation of H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, which had put much of the country in a panic. [10] By all accounts, Welles was shocked by the panic that ensued. According to Houseman, "he hadn't the faintest idea what the effect would be". CBS was inundated with calls; newspaper switchboards were jammed. While Houseman was teaching at Vassar he produced Welles’ never completed first film entitled, Too Much Johnson (1938). The film was never publicly screened and no print of the film survives to this day.

Citizen Kane (1941)

The Welles-Houseman collaboration continued in Hollywood. In the spring of 1939, Welles began preliminary discussions with RKO's head of production, George Schaefer, with Welles and his Mercury players being given a generous two-picture deal, in which Welles would produce, direct, perform, and have full creative control of his projects.

For his motion picture debut, Welles first considered adapting Joseph Conrad's dark tale Heart of Darkness for the screen. A 200-page script was written. Some models were constructed, while the shooting of initial test footage had begun. However, little, if anything, had been done either to whittle down the budgetary difficulties or begin filming. When RKO threatened to eliminate the payment of salaries by December 31 if no progress had been made, Welles announced that he would pay his cast out of his own pocket. Houseman proclaimed that there wasn't enough money in their business account to pay anyone. During a corporate dinner for the Mercury crew, Welles exploded, calling his partner a "bloodsucker" and a "crook". As Houseman attempted to leave, Welles began hurling dish heaters at him, effectively ending both their partnership and friendship[11].

Houseman would later, however, play a pivotal role in ushering Citizen Kane (1941), to the big screen. Welles telephoned Houseman asking him to return to Hollywood in order to "baby sit" screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz while he completed the script, and keep him away from alcohol. Still drawn to Welles, as was virtually everyone in his sphere, Houseman agreed. Although Welles took credit for the screenplay of Kane Houseman stated that the credit belonged to Mankiewicz, an assertion that led to a final break with Welles. Houseman took some credit himself for the general shaping of the story line and for editing the script. In an interview with Penelope Huston for Sight & Sound magazine (Autumn, 1962) Houseman said that the writing of Citizen Kane was a delicate subject:

"I think Welles has always sincerely felt that he, single-handed, wrote Citizen Kane and everything else that he has directed—except, possibly, the plays of Shakespeare. But the script of Kane was essentially Mankiewicz’s. The conception and the structure were his, all the dramatic Hearstian mythology and the journalistic and political wisdom which he had been carrying around with him for years and which he now poured into the only serious job he ever did in a lifetime of film writing. But Orson turned Kane into a film: the dynamics and the tensions are his and the brilliant cinematic effects—all those visual and aural inventions that add up to make Citizen Kane one of the world’s great movies—those were pure Orson Welles."

In 1975, during an interview with Kate McCauley, Houseman stated that film critic Pauline Kael in her tome, The Citizen Kane Book, had caused an “idiotic controversy” over the issue:

"The argument is Orson’s own fault. He wanted to be given all the credit because he’s a hog."

Later years

After going their separate ways, Houseman would go on to direct The Devil and Daniel Webster (1939) and Liberty Jones and produced Native Son (1941) on Broadway. In Hollywood he became a Vice-President of David O. Selznick Productions.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Houseman quit his job and became the head of the overseas radio division of the O.W.I. working for the Voice of America whilst also managing its operations in New York.[12]

Between 1945 and 1962 he produced 18 films for Paramount, Universal and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, including the 1946 film noir, The Blue Dahlia and the 1953 film adaptation of Julius Caesar (for which he received an Academy Award nomination for "Best Picture"). He first became widely known to the public, however, for his Golden Globe and Academy Award-winning role as Professor Charles Kingsfield in the 1973 film The Paper Chase. He reprised his role in the television series of the same name from 1978-1986, receiving two Golden Globe nominations for "Best Actor in a TV Series - Drama".

He was the executive producer of CBS' landmark Seven Lively Arts series. Houseman played Energy Corporation Executive Bartholomew in the 1975 film Rollerball and parodied Sydney Greenstreet in the 1978 Neil Simon film, The Cheap Detective.

In the 1980s, Houseman became more widely known for his role as grandfather Edward Stratton II in Silver Spoons, which starred Rick Schroder, and for his commercials for brokerage firm Smith Barney, which featured the catchphrase, "They make money the old fashioned way...they earn it." Another was Puritan brand cooking oil, with "less saturated fat than the leading oil", featuring the famous 'tomato test'. He also made a guest appearance in John Carpenter's 1980 movie The Fog as Mr. Machen. He played the Jewish professor Aaron Jastrow in the 1983 miniseries The Winds of War (receiving a fourth Golden Globe nomination).

Houseman taught acting at The Juilliard School where his first graduating class included Kevin Kline and Patti LuPone. Unwilling to see his first class immediately disbanded by the testing world of stage and screen, he formed them into a touring repertory company appropriately named the Group 1 Acting Company. The troupe later shortened its name simply to The Acting Company.

In 1988, he appeared in The Naked Gun and Scrooged, which were released after his death.

Filmography

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Too Much Johnson | Duelist | |

| 1964 | Seven Days in May | Vice-Adm. Farley C. Barnswell | uncredited |

| 1973 | The Paper Chase | Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. | Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe |

| 1975 | Three Days of the Condor | Wabash | |

| Rollerball | Bartholomew | ||

| 1976 | St. Ives | Abner Procane | |

| 1978 | The Cheap Detective | Jasper Blubber | |

| 1979 | Old Boyfriends | Doctor Hoffman | |

| 1980 | The Fog | Mr. Machen | |

| A Christmas Without Snow | Ephraim Adams | ||

| My Bodyguard | Mr. Dobbs | ||

| Wholly Moses! | The Archangel | ||

| 1981 | Ghost Story | Sears James | |

| 1982 | Rose for Emily | Narrator | |

| Murder by Phone | Stanley Markowitz | ||

| 1988 | The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! | Driving Instructor | uncredited |

| Another Woman | Marion's Father | ||

| Bright Lights, Big City | Mr. Vogel | ||

| Scrooged | Himself |

References

- ^ Magill, Frank Northen (1977). Survey of Contemporary Literature. Salem Pr. Inc. p. 6535. ISBN 0893560502.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. p. 15. ISBN.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ John Houseman. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ John Houseman New York Times Movies.

- ^ John Houseman

- ^ John Houseman at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Anthony Tommasini (1997) "Virgil Thomson -- Composer on the Aisle," pp 241-243.

- ^ a b c Houseman, John, Run Through: A Memoir, New York, 1972.

- ^ http://www.filmreference.com/Directors-Ve-Y/Welles-Orson.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://www.viewzone.com/orson.html

- ^ "The Beginning: An American Voice Greets the World". Voice of America.

External links

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- "The Theatre: Marvelous Boy" - Time Magazine May 9, 1938

- Interviews with Howard Koch on the infamous Mercury Theatre's War of the Worlds radio broadcast

- English actors

- English film actors

- American actors

- American film actors

- Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winners

- Old Cliftonians

- Juilliard School faculty

- Naturalized citizens of the United States

- English Americans

- English people of Romanian descent

- English people of German descent

- English people of French descent

- English people of Welsh descent

- English people of Irish descent

- British expatriates in Romania

- Romanians of British descent

- German-Romanians

- French-Romanians

- Paternal Jews

- Alsatian Jews

- Romanian Jews

- English Jews

- American Jews

- People from Bucharest

- Cancer deaths in California

- Deaths from spinal cancer

- 1902 births

- 1988 deaths