Haematopoiesis: Difference between revisions

Antibody2000 (talk | contribs) Reversion of deleted section |

Edited spelling of "haematopoiesis" to maintain consistency within the page. Used British spelling due to preferences given by users on "Discussion" page and also preference of Wikipedia spell-check. |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

'''Haematopoiesis''' (from Ancient Greek: ''haima'' blood; ''poiesis'' to make) (or '''hematopoiesis''' in the United States; sometimes also '''haemopoiesis''' or '''hemopoiesis''') is the formation of [[blood]] cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from [[haematopoietic stem cell]]s. In a healthy adult person, approximately 10<sup>11</sup>–10<sup>12</sup> new blood cells are produced daily in order to maintain steady state levels in the peripheral circulation.<ref name = T4/> |

'''Haematopoiesis''' (from Ancient Greek: ''haima'' blood; ''poiesis'' to make) (or '''hematopoiesis''' in the United States; sometimes also '''haemopoiesis''' or '''hemopoiesis''') is the formation of [[blood]] cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from [[haematopoietic stem cell]]s. In a healthy adult person, approximately 10<sup>11</sup>–10<sup>12</sup> new blood cells are produced daily in order to maintain steady state levels in the peripheral circulation.<ref name = T4/> |

||

== |

== Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) == |

||

[[Hematopoietic stem cells]] (HSCs) reside in the medulla (bone marrow) and have the unique ability to give rise to all of the different mature blood cell types. HSCs are self renewing: when they proliferate, at least some of their daughter cells remain as HSCs, so the pool of stem cells does not become depleted. The other daughters of HSCs (myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells), however can each commit to any of alternative differentiation pathways that lead to the production of one or more specific types of blood cells, but cannot self |

[[Hematopoietic stem cells|Haematopoietic stem cells]] (HSCs) reside in the medulla (bone marrow) and have the unique ability to give rise to all of the different mature blood cell types. HSCs are self renewing: when they proliferate, at least some of their daughter cells remain as HSCs, so the pool of stem cells does not become depleted. The other daughters of HSCs (myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells), however can each commit to any of alternative differentiation pathways that lead to the production of one or more specific types of blood cells, but cannot self-renew. This is one of the vital processes in the body. |

||

==Lineages== |

==Lineages== |

||

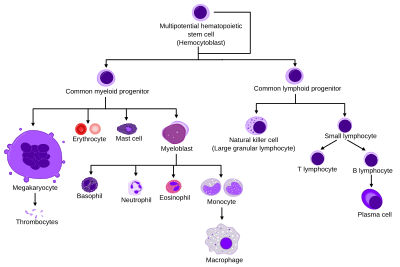

[[Image:Hematopoiesis (human) diagram.png|thumb|400px|Comprehensive diagram that shows the development of different blood cells from |

[[Image:Hematopoiesis (human) diagram.png|thumb|400px|Comprehensive diagram that shows the development of different blood cells from haematopoietic stem cell to mature cells]] |

||

All blood cells are divided into three lineages. |

All blood cells are divided into three lineages. |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

* [[Myelocyte|Myelocytes]], which include [[granulocyte]]s, [[megakaryocyte]]s and [[macrophage]]s and are derived from common myeloid progenitors, are involved in such diverse roles as [[innate immunity]], [[adaptive immunity]], and [[blood clotting]]. This is [[myelopoiesis]]. |

* [[Myelocyte|Myelocytes]], which include [[granulocyte]]s, [[megakaryocyte]]s and [[macrophage]]s and are derived from common myeloid progenitors, are involved in such diverse roles as [[innate immunity]], [[adaptive immunity]], and [[blood clotting]]. This is [[myelopoiesis]]. |

||

[[Granulopoiesis]] (or granulocytopoiesis) is |

[[Granulopoiesis]] (or granulocytopoiesis) is haematopoiesis of [[granulocytes]]. |

||

==Locations== |

==Locations== |

||

In developing embryos, blood formation occurs in aggregates of blood cells in the yolk sac, called [[blood islands]]. As development progresses, blood formation occurs in the [[spleen]], [[liver]] and [[lymph node]]s. When [[bone marrow]] develops, it eventually assumes the task of forming most of the blood cells for the entire organism. However, maturation, activation, and some proliferation of lymphoid cells occurs in secondary lymphoid organs (spleen, [[thymus]], and lymph nodes). In children, |

In developing embryos, blood formation occurs in aggregates of blood cells in the yolk sac, called [[blood islands]]. As development progresses, blood formation occurs in the [[spleen]], [[liver]] and [[lymph node]]s. When [[bone marrow]] develops, it eventually assumes the task of forming most of the blood cells for the entire organism. However, maturation, activation, and some proliferation of lymphoid cells occurs in secondary lymphoid organs (spleen, [[thymus]], and lymph nodes). In children, haematopoiesis occurs in the marrow of the long bones such as the femur and tibia. In adults, it occurs mainly in the pelvis, cranium, vertebrae, and sternum. |

||

===Extramedullary=== |

===Extramedullary=== |

||

In some cases, the liver, thymus, and spleen may resume their haematopoietic function, if necessary. This is called ''[[extramedullary hematopoiesis]]''. It may cause these organs to increase in size substantially. |

In some cases, the liver, thymus, and spleen may resume their haematopoietic function, if necessary. This is called ''[[extramedullary hematopoiesis|extramedullary haematopoiesis]]''. It may cause these organs to increase in size substantially. |

||

During fetal development, since bones and thus the bone marrow, develop later, the liver functions as the main |

During fetal development, since bones and thus the bone marrow, develop later, the liver functions as the main haematopoetic organ. Therefore, the liver is enlarged during development. |

||

<ref name=T4> Semester 4 medical lectures at Uppsala University 2008 by Leif Jansson</ref> |

<ref name=T4> Semester 4 medical lectures at Uppsala University 2008 by Leif Jansson</ref> |

||

<ref name=T6> Semester 1 veterinary medicine lectures at UPENN 2009 by J.A.K </ref> |

<ref name=T6> Semester 1 veterinary medicine lectures at UPENN 2009 by J.A.K </ref> |

||

===Other vertebrates=== |

===Other vertebrates=== |

||

In some [[vertebrate]]s, |

In some [[vertebrate]]s, haematopoiesis can occur wherever there is a loose [[stroma]] of connective tissue and slow blood supply, such as the [[gut]], [[spleen]], [[kidney]] or [[ovaries]]. |

||

==Maturation== |

==Maturation== |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

=== Determination === |

=== Determination === |

||

[[Cell determination]] appears to be dictated by the location of differentiation.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} For instance, the [[thymus]] provides an ideal environment for thymocytes to differentiate into a variety of different functional T cells. For the stem cells and other undifferentiated blood cells in the bone marrow, the determination is generally explained by the ''determinism'' theory of |

[[Cell determination]] appears to be dictated by the location of differentiation.{{Fact|date=September 2008}} For instance, the [[thymus]] provides an ideal environment for thymocytes to differentiate into a variety of different functional T cells. For the stem cells and other undifferentiated blood cells in the bone marrow, the determination is generally explained by the ''determinism'' theory of haematopoiesis, saying that colony stimulating factors and other factors of the haematopoietic microenvironment determine the cells to follow a certain path of cell differentiation. This is the classical way of describing haematopoiesis. In fact, however, it is not really true. The ability of the bone marrow to regulate the quantity of different cell types to be produced is more accurately explained by a ''stochastic'' theory: Undifferentiated blood cells are determined to specific cell types by randomness. The haematopoietic microenvironment prevails upon some of the cells to survive and some, on the other hand, to perform [[apoptosis]] and die. By regulating this balance between different cell types, the bone marrow can alter the quantity of different cells to ultimately be produced. |

||

=== Haematopoietic growth factors === |

=== Haematopoietic growth factors === |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

=== The myeloid-based model === |

=== The myeloid-based model === |

||

For a decade now, the evidence is growing that HSC maturation follows a myeloid-based model instead of the 'classical' schoolbook dichotomy model. In the latter model, the HSC first generates a common myeloid-erythroid progenitor (CMEP) and a common lymphoid progenitor (CLP). The CLP produces only T or B cells. The myeloid-based model postulates that HSCs first diverge into the CMEP and a common myelo-lymphoid progenitor (CMLP), which generates T and B cell progenitors through a bipotential myeloid-T progenitor and a myeloid-B progenitor stage. The main difference is that in this new model, all erythroid, T and B lineage branches retain the potential to generate myeloid cells (even after the segregation of T and B cell lineages). The model proposes the idea of erythroid, T and B cells as specialized types of a prototypic myeloid HSC. Read more in Kawamoto et al. 2010.<ref>Kawamoto, Wada, Katsura. A revised scheme for developmental pathways of |

For a decade now, the evidence is growing that HSC maturation follows a myeloid-based model instead of the 'classical' schoolbook dichotomy model. In the latter model, the HSC first generates a common myeloid-erythroid progenitor (CMEP) and a common lymphoid progenitor (CLP). The CLP produces only T or B cells. The myeloid-based model postulates that HSCs first diverge into the CMEP and a common myelo-lymphoid progenitor (CMLP), which generates T and B cell progenitors through a bipotential myeloid-T progenitor and a myeloid-B progenitor stage. The main difference is that in this new model, all erythroid, T and B lineage branches retain the potential to generate myeloid cells (even after the segregation of T and B cell lineages). The model proposes the idea of erythroid, T and B cells as specialized types of a prototypic myeloid HSC. Read more in Kawamoto et al. 2010.<ref>Kawamoto, Wada, Katsura. A revised scheme for developmental pathways of haematopoietic cells: the myeloid-based model. International Immunology 2010.</ref> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 20:28, 18 February 2010

Haematopoiesis (from Ancient Greek: haima blood; poiesis to make) (or hematopoiesis in the United States; sometimes also haemopoiesis or hemopoiesis) is the formation of blood cellular components. All cellular blood components are derived from haematopoietic stem cells. In a healthy adult person, approximately 1011–1012 new blood cells are produced daily in order to maintain steady state levels in the peripheral circulation.[1]

Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)

Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the medulla (bone marrow) and have the unique ability to give rise to all of the different mature blood cell types. HSCs are self renewing: when they proliferate, at least some of their daughter cells remain as HSCs, so the pool of stem cells does not become depleted. The other daughters of HSCs (myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells), however can each commit to any of alternative differentiation pathways that lead to the production of one or more specific types of blood cells, but cannot self-renew. This is one of the vital processes in the body.

Lineages

All blood cells are divided into three lineages.

- Erythroid cells are the oxygen carrying red blood cells. Both reticulocytes and erythrocytes are functional and are released into the blood. In fact, a reticulocyte count estimates the rate of erythropoiesis.

- Lymphocytes are the cornerstone of the adaptive immune system. They are derived from common lymphoid progenitors. The lymphoid lineage is primarily composed of T-cells and B-cells (types of white blood cells). This is lymphopoiesis.

- Myelocytes, which include granulocytes, megakaryocytes and macrophages and are derived from common myeloid progenitors, are involved in such diverse roles as innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and blood clotting. This is myelopoiesis.

Granulopoiesis (or granulocytopoiesis) is haematopoiesis of granulocytes.

Locations

In developing embryos, blood formation occurs in aggregates of blood cells in the yolk sac, called blood islands. As development progresses, blood formation occurs in the spleen, liver and lymph nodes. When bone marrow develops, it eventually assumes the task of forming most of the blood cells for the entire organism. However, maturation, activation, and some proliferation of lymphoid cells occurs in secondary lymphoid organs (spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes). In children, haematopoiesis occurs in the marrow of the long bones such as the femur and tibia. In adults, it occurs mainly in the pelvis, cranium, vertebrae, and sternum.

Extramedullary

In some cases, the liver, thymus, and spleen may resume their haematopoietic function, if necessary. This is called extramedullary haematopoiesis. It may cause these organs to increase in size substantially. During fetal development, since bones and thus the bone marrow, develop later, the liver functions as the main haematopoetic organ. Therefore, the liver is enlarged during development. [1] [2]

Other vertebrates

In some vertebrates, haematopoiesis can occur wherever there is a loose stroma of connective tissue and slow blood supply, such as the gut, spleen, kidney or ovaries.

Maturation

As a stem cell matures it undergoes changes in gene expression that limit the cell types that it can become and moves it closer to a specific cell type. These changes can often be tracked by monitoring the presence of proteins on the surface of the cell. Each successive change moves the cell closer to the final cell type and further limits its potential to become a different cell type.

Determination

Cell determination appears to be dictated by the location of differentiation.[citation needed] For instance, the thymus provides an ideal environment for thymocytes to differentiate into a variety of different functional T cells. For the stem cells and other undifferentiated blood cells in the bone marrow, the determination is generally explained by the determinism theory of haematopoiesis, saying that colony stimulating factors and other factors of the haematopoietic microenvironment determine the cells to follow a certain path of cell differentiation. This is the classical way of describing haematopoiesis. In fact, however, it is not really true. The ability of the bone marrow to regulate the quantity of different cell types to be produced is more accurately explained by a stochastic theory: Undifferentiated blood cells are determined to specific cell types by randomness. The haematopoietic microenvironment prevails upon some of the cells to survive and some, on the other hand, to perform apoptosis and die. By regulating this balance between different cell types, the bone marrow can alter the quantity of different cells to ultimately be produced.

Haematopoietic growth factors

Red and white blood cell production is regulated with great precision in healthy humans, and the production of granulocytes is rapidly increased during infection. The proliferation and self-renewal of these cells depend on stem cell factor (SCF). Glycoprotein growth factors regulate the proliferation and maturation of the cells that enter the blood from the marrow, and cause cells in one or more committed cell lines to proliferate and mature. Three more factors that stimulate the production of committed stem cells are called colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) and include granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), granulocyte CSF (G-CSF) and macrophage CSF (M-CSF). These stimulate much granulocyte formation and are active on either progenitor cells or end product cells.

Erythropoietin is required for a myeloid progenitor cell to become an erythrocyte. [3] On the other hand, thrombopoietin makes myeloid progenitor cells differentiate to megakaryocytes (thrombocyte-forming cells).[3] Examples of cytokines and the blood cells they give rise to, is shown in the picture to the right.

Transcription factors

Growth factors initiate signal transduction pathways, altering transcription factors, that, in turn activate genes that determine the differentiation of blood cells.

The early committed progenitors express low levels of transcription factors that may commit them to discrete cell lineages. Which cell lineage is selected for differentiation may depend both on chance and on the external signals received by progenitor cells. Several transcription factors have been isolated that regulate differentiation along the major cell lineages. For instance, PU.1 commits cells to the myeloid lineage whereas GATA-1 has an essential role in erythropoietic and megakaryocytic differentiation. The Ikaros, Aiolos and Helios transcription factors play a major role in lymphoid development.[4]

The myeloid-based model

For a decade now, the evidence is growing that HSC maturation follows a myeloid-based model instead of the 'classical' schoolbook dichotomy model. In the latter model, the HSC first generates a common myeloid-erythroid progenitor (CMEP) and a common lymphoid progenitor (CLP). The CLP produces only T or B cells. The myeloid-based model postulates that HSCs first diverge into the CMEP and a common myelo-lymphoid progenitor (CMLP), which generates T and B cell progenitors through a bipotential myeloid-T progenitor and a myeloid-B progenitor stage. The main difference is that in this new model, all erythroid, T and B lineage branches retain the potential to generate myeloid cells (even after the segregation of T and B cell lineages). The model proposes the idea of erythroid, T and B cells as specialized types of a prototypic myeloid HSC. Read more in Kawamoto et al. 2010.[5]

References

- ^ a b Semester 4 medical lectures at Uppsala University 2008 by Leif Jansson

- ^ Semester 1 veterinary medicine lectures at UPENN 2009 by J.A.K

- ^ a b c Molecular cell biology. Lodish, Harvey F. 5. ed. : - New York : W. H. Freeman and Co., 2003, 973 s. b ill. ISBN 0-7167-4366-3

- ^ Rebollo, A. (2003). "Ikaros, Aiolos and Helios: Transcription regulators and lymphoid malignancies". Immunology and Cell Biology. 81: 171–175. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01159.x. PMID 12752680.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kawamoto, Wada, Katsura. A revised scheme for developmental pathways of haematopoietic cells: the myeloid-based model. International Immunology 2010.

- Parslow,T G.;Stites, DP.; Terr, AI.; and Imboden JB.Medical Immunology.1.ISBN 0838562787

External links

{{Diseases of RBCs and megakaryocytes}} may refer to:

- {{Diseases of RBCs}}, a navigational template for diseases of red blood cells

- {{Diseases of megakaryocytes}}, a navigational template for diseases of clotting

{{Template disambiguation}} should never be transcluded in the main namespace.