History of paper: Difference between revisions

pic |

→Paper mills: water-powered |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

A paper mill is [[watermill|water-powered mill]] that pounds the pulp by the use of trip-hammers. The mechanization of the pounding process was an important improvement in paper manufacture over the manual pounding with [[Mortar and pestle|hand pestles]]. |

A paper mill is [[watermill|water-powered mill]] that pounds the pulp by the use of trip-hammers. The mechanization of the pounding process was an important improvement in paper manufacture over the manual pounding with [[Mortar and pestle|hand pestles]]. |

||

Evidence for paper mills is elusive in both Chinese<ref>Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, pp. 68−73</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Lucas|2005|p=28, fn. 70}}</ref> and Muslim [[papermaking]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 414f.">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414f.}}: {{quote|It has also become universal to talk of paper "mills" (even of 400 such mills at [[Fes|Fez]]!), relating these to the hydraulic wonders of Islamic society in east and west. All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Thompson|1978|p=169}}: {{quote|European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power. [[Jean Gimpel]], in ''The Medieval Machine'' (the English translation of ''La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age''), points out that the Chinese and Arabs used only human and animal force. Gimpel goes on to say : "This is convincing evidence of how technologically minded the Europeans of that era were. Paper had traveled nearly halfway around the world, but no culture or civilization on its route had tried to mechanize its manufacture."'}}</ref> The general absence of the use of water-power in Muslim papermaking is suggested by the habit of Muslim authors to call a production center a "paper manufactory", but not a "mill".<ref>{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414f.}}: {{quote|Indeed, Muslim authors in general call any "paper manufactory" a ''wiraqah'' - not a "mill" (''tahun'')}}</ref> |

Evidence for water-powered paper mills is elusive in both Chinese<ref>Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, pp. 68−73</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Lucas|2005|p=28, fn. 70}}</ref> and Muslim [[papermaking]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 414f.">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414f.}}: {{quote|It has also become universal to talk of paper "mills" (even of 400 such mills at [[Fes|Fez]]!), relating these to the hydraulic wonders of Islamic society in east and west. All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Thompson|1978|p=169}}: {{quote|European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power. [[Jean Gimpel]], in ''The Medieval Machine'' (the English translation of ''La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age''), points out that the Chinese and Arabs used only human and animal force. Gimpel goes on to say : "This is convincing evidence of how technologically minded the Europeans of that era were. Paper had traveled nearly halfway around the world, but no culture or civilization on its route had tried to mechanize its manufacture."'}}</ref> The general absence of the use of water-power in Muslim papermaking is suggested by the habit of Muslim authors to call a production center a "paper manufactory", but not a "mill".<ref>{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414f.}}: {{quote|Indeed, Muslim authors in general call any "paper manufactory" a ''wiraqah'' - not a "mill" (''tahun'')}}</ref> |

||

[[Donald Routledge Hill|Donald Hill]] has identified a possible reference to a water-powered [[paper mill]] in Samarkand, in the 11th-century work of the Persian scholar [[Abu Rayhan Biruni]], but concludes that the passage is "too brief to enable us to say with certainty" that it refers to a water-powered paper mill.<ref>{{citation|title=A history of engineering in classical and medieval times|author=[[Donald Routledge Hill]]|publisher=[[Routledge]]|year=1996|isbn=0415152917|pages=169-71}}</ref> While this is seen by Halevi nonetheless as evidence of Samarkand first harnessing waterpower in the production of paper, he concedes that it is not known if waterpower was applied to papermaking elsewhere across the Islamic world at the time;<ref>{{citation|title=Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper|author=Leor Halevi|journal=[[Speculum (journal)|Speculum]]|year=2008|volume=83|pages=917-945 [917-8]|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]]|doi=10.1017/S0038713400017073}}</ref> Burns remains altogether sceptical given the isolated occurrence of the reference and the prevalence of manual labour in Islamic papermaking elsewhere.<ref name="Burns 1996, 414−417">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414−417}}</ref> |

[[Donald Routledge Hill|Donald Hill]] has identified a possible reference to a water-powered [[paper mill]] in Samarkand, in the 11th-century work of the Persian scholar [[Abu Rayhan Biruni]], but concludes that the passage is "too brief to enable us to say with certainty" that it refers to a water-powered paper mill.<ref>{{citation|title=A history of engineering in classical and medieval times|author=[[Donald Routledge Hill]]|publisher=[[Routledge]]|year=1996|isbn=0415152917|pages=169-71}}</ref> While this is seen by Halevi nonetheless as evidence of Samarkand first harnessing waterpower in the production of paper, he concedes that it is not known if waterpower was applied to papermaking elsewhere across the Islamic world at the time;<ref>{{citation|title=Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper|author=Leor Halevi|journal=[[Speculum (journal)|Speculum]]|year=2008|volume=83|pages=917-945 [917-8]|publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]]|doi=10.1017/S0038713400017073}}</ref> Burns remains altogether sceptical given the isolated occurrence of the reference and the prevalence of manual labour in Islamic papermaking elsewhere.<ref name="Burns 1996, 414−417">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=414−417}}</ref> |

||

The earliest certain evidence to a paper mill dates to 1282 in the Spanish [[Kingdom of Aragon]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f.">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=417f.}}</ref> A decree by the Christian king [[Peter III of Aragon|Peter III]] addresses the establishment of a royal "[[Watermill|molendinum]]", a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of [[Xàtiva]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f."/> The crown innovation appears to be resented by the local Muslim papermakering community; the document guarantees the Muslim subjects the right to continue their way of traditional papermaking by beating the pulp manually and grants them the right to be exempted from work in the new mill.<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f."/> |

The earliest certain evidence to a water-powered paper mill dates to 1282 in the Spanish [[Kingdom of Aragon]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f.">{{harvnb|Burns|1996|pp=417f.}}</ref> A decree by the Christian king [[Peter III of Aragon|Peter III]] addresses the establishment of a royal "[[Watermill|molendinum]]", a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of [[Xàtiva]].<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f."/> The crown innovation appears to be resented by the local Muslim papermakering community; the document guarantees the Muslim subjects the right to continue their way of traditional papermaking by beating the pulp manually and grants them the right to be exempted from work in the new mill.<ref name="Burns 1996, 417f."/> |

||

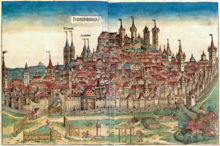

The first paper mill north of the Alpes was established in [[Nuremberg]] by [[Ulman Stromer]] in 1390; it is later depicted in the lavishly illustrated ''[[Nuremberg Chronicle]]''.<ref>{{harvnb|Stromer|1960}}</ref> From the mid-14th century onwards, European paper milling underwent a rapid improvement of many work processes.<ref>{{harvnb|Stromer|1993|p=1}}</ref> |

The first paper mill north of the Alpes was established in [[Nuremberg]] by [[Ulman Stromer]] in 1390; it is later depicted in the lavishly illustrated ''[[Nuremberg Chronicle]]''.<ref>{{harvnb|Stromer|1960}}</ref> From the mid-14th century onwards, European paper milling underwent a rapid improvement of many work processes.<ref>{{harvnb|Stromer|1993|p=1}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:13, 26 March 2010

The history of paper began in Ancient Egypt aprox. 3,700 BC - 3,200 BC (approx. 5,700 to 5,200 years before present) with the use of papyrus as a medium for written records, a considerable advance over the technique employed by the Sumerians of writing on clay tablets. The transition from clay tablets to papyrus was as revolutionary as the step from manuscripts to printing. The word "paper" is etymologically derived from papyros, Ancient Greek for the Cyperus papyrus, while "book" is derived from biblos, a Greek term signifying the bark of the plant. The Greek writer Theophrastus used the word papyros to refer to plant as a foodstuff, whereas bublos signified any derived processed product, such as cordage or as a writing surface. The Chinese independently developed a papermaking process during the Han Dynasty, between 202 BC and 220 AD, which is where modern paper originated.

Papyrus and Parchment

The word paper derives from the Greek term for the ancient Egyptian writing material called papyrus, which was formed from beaten strips of papyrus plants. It was smoothed on one side by rubbing it against a flat stone surface.[1] Papyrus was produced as early as 3700 BC in Egypt[citation needed], and later exported to both ancient Greece and Rome. The establishment of the Library of Alexandria in the 3rd century BC put a drain on the supply of papyrus. As a result, according to the Roman historian Pliny the Elder (Natural History records, xiii.21), parchment was invented under the patronage of Eumenes of Pergamum to build his rival library at Pergamum. Outside Egypt, parchment or vellum, made of processed sheepskin or calfskin, replaced papyrus, as the papyrus plant requires subtropical conditions to grow. These materials are technically not true paper, which is made from pulp, rags, and fibers of plants and cellulose. As paper was introduced, it replaced parchment.

Papermaking

Papermaking has traditionally been traced to China about 105 AD, when Cai Lun, an official attached to the Imperial court during the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD), created a sheet of paper using mulberry and other bast fibres along with fishnets, old rags, and hemp waste.[2]

Early papermaking in China

Papermaking is considered to be one of the Four Great Inventions of Ancient China, since the first papermaking process was developed in China during the early 2nd century. During the Shang (1600–1050 BC) and Zhou (1050 BC – 256 AD) dynasties of ancient China, documents were ordinarily written on bone or bamboo (on tablets or on bamboo strips sewn and rolled together into scrolls), making them very heavy and awkward to transport. The light material of silk was sometimes used, but was normally too expensive to consider. While the Han Dynasty Chinese court official Cai Lun is widely regarded to have invented the modern method of papermaking (inspired from wasps and bees) from rags and other plant fibers in 105 CE, the discovery of specimens bearing written Chinese characters in 2006 at north-east China's Gansu province suggest that paper was in use by the ancient Chinese military more than 100 years before Cai, in 8 BC. [1] Archeologically however, ground paper without writing has been excavated in China dating to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han from the 2nd century BC, used for purposes of wrapping or padding protection for delicate bronze mirrors.[3] It was also used for safety, such as the padding of poisonous 'medicine' as mentioned in the official history of the period.[3] Although paper used for writing became widespread by the 3rd century,[4] paper continued to be used for wrapping (and other) purposes.

Toilet paper was used in China by at least the 6th century CE.[5] In 589 AD, the Chinese scholar-official Yan Zhitui (531-591 AD) once wrote: "Paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes".[5] An Arab traveler to China once wrote of the curious Chinese tradition of toilet paper in AD 851, writing: "[The Chinese] are not careful about cleanliness, and they do not wash themselves with water when they have done their necessities; but they only wipe themselves with paper".[5] Toilet paper continued to be a valued necessity in China, since it was during the Hongwu Emperor's reign in 1393 that the Bureau of Imperial Supplies (Bao Chao Si) manufactured 720,000 sheets of toilet paper for the entire court (produced of the cheap rice–straw paper).[5] For the emperor's family alone, 15,000 special sheets of paper were made, in light yellow tint and even perfumed.[5] Even at the beginning of the 14th century, during the middle of the Yuan Dynasty, the amount of toilet paper manufactured for modern-day Zhejiang province alone amounted to ten million packages holding 1,000 to 10,000 sheets of toilet paper each.[5]

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) paper was folded and sewn into square bags to preserve the flavor of tea.[3] During the same period, it was written that tea was served from baskets with multi-colored paper cups and paper napkins of different size and shape.[3] During the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD) not only did the government produce the world's first known paper-printed money, or banknote (see Jiaozi and Huizi), but paper money bestowed as gifts to deserving government officials were wrapped in special paper envelopes.[5]

Diffusion of paper

Paper spread slowly outside of China; other East Asian cultures, even after seeing paper, could not make it themselves[citation needed]. Instruction in the manufacturing process was required, and the Chinese were reluctant to share their secrets. The paper was thin and translucent, not like modern western paper, and thus only written on one side. The technology was first transferred to Goguryeo in 604 and then imported to Japan by Buddhist priests, around 610, where fibres (called bast) from the mulberry tree were used.[citation needed]

Some historians[who?] speculate that paper was a key element in cultural advancement[citation needed]. According to this theory, Chinese culture was less developed than the West in ancient times prior to the Han Dynasty because bamboo, while abundant, was a clumsier writing material than papyrus; Chinese culture advanced during the Han Dynasty and subsequent centuries due to the invention of paper; and Europe advanced during the Renaissance due to the introduction of paper and the printing press.

Islamic world

After the defeat of the Chinese in the Battle of Talas in 751 (present day Kyrgyzstan), the invention spread to the Middle East.[6] The rudimentary and laborious process of paper making was refined and machinery was designed for bulk manufacturing of paper by Muslims. Production began in Baghdad, where the Arab Muslims invented a method to make a thicker sheet of paper, which helped transform papermaking from an art into a major industry.[7][8]

The Arabs also made advances in book production soon after they learnt papermaking from the Chinese in the 8th century.[9] Particular skills were developed for script writing (Arabic calligraphy), miniatures and bookbinding. The Arabs made books lighter—sewn with silk and bound with leather-covered paste boards; they had a flap that wrapped the book up when not in use. As paper was less reactive to humidity, the heavy boards were not needed. The production of books became a real industry and cities like Marrakech in Morocco had a street named "Kutubiyyin" or book sellers which contained more than 100 bookshops by the 12th century.[10] In the words of Don Baker: "The world of Islam has produced some of the most beautiful books ever created. [...] Splendid illumination was added with gold and vibrant colours, and the whole book contained and protected by beautiful bookbindings."[11] The earliest recorded use of paper for packaging dates back to 1035, when a Persian traveler visiting markets in Cairo noted that vegetables, spices and hardware were wrapped in paper for the customers after they were sold.[12]

Since the First Crusade in 1096, paper manufacturing in Damascus had been interrupted by wars, splitting production into two centres. Egypt continued with the thicker paper, while Iran became the center of the thinner papers. Papermaking was diffused across the Islamic world, from where it was diffused further west into Europe.[13]

Americas

In America, archaeological evidence indicates that a similar parchment writing material was invented by the Mayans no later than the 5th century CE.[14] Called amatl, it was in widespread use among Mesoamerican cultures until the Spanish conquest. The parchment is created by boiling and pounding the inner bark of trees, until the material becomes suitable for art and writing.

These materials made from pounded reeds and bark are technically not true paper, which is made from pulp, rags, and fibers of plants and cellulose.

Europe

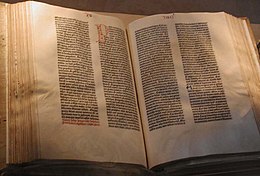

The oldest known paper document in the West is the Mozarab Missal of Silos from the 11th century, probably written in the Islamic part of Spain. They used hemp and linen rags as a source of fibre.

Paper is recorded as being manufactured in both Italy and Germany by 1400, just about the time when the woodcut printmaking technique was transferred from fabric to paper in the old master print and popular prints. The first commercially successful paper mill in England was opened by John Spilman in 1588 near Dartford in Kent and was initially reliant on German papermaking expertise.[citation needed]

Paper mills

A paper mill is water-powered mill that pounds the pulp by the use of trip-hammers. The mechanization of the pounding process was an important improvement in paper manufacture over the manual pounding with hand pestles.

Evidence for water-powered paper mills is elusive in both Chinese[15][16] and Muslim papermaking.[17][18] The general absence of the use of water-power in Muslim papermaking is suggested by the habit of Muslim authors to call a production center a "paper manufactory", but not a "mill".[19]

Donald Hill has identified a possible reference to a water-powered paper mill in Samarkand, in the 11th-century work of the Persian scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni, but concludes that the passage is "too brief to enable us to say with certainty" that it refers to a water-powered paper mill.[20] While this is seen by Halevi nonetheless as evidence of Samarkand first harnessing waterpower in the production of paper, he concedes that it is not known if waterpower was applied to papermaking elsewhere across the Islamic world at the time;[21] Burns remains altogether sceptical given the isolated occurrence of the reference and the prevalence of manual labour in Islamic papermaking elsewhere.[22]

The earliest certain evidence to a water-powered paper mill dates to 1282 in the Spanish Kingdom of Aragon.[23] A decree by the Christian king Peter III addresses the establishment of a royal "molendinum", a proper hydraulic mill, in the paper manufacturing centre of Xàtiva.[23] The crown innovation appears to be resented by the local Muslim papermakering community; the document guarantees the Muslim subjects the right to continue their way of traditional papermaking by beating the pulp manually and grants them the right to be exempted from work in the new mill.[23]

The first paper mill north of the Alpes was established in Nuremberg by Ulman Stromer in 1390; it is later depicted in the lavishly illustrated Nuremberg Chronicle.[24] From the mid-14th century onwards, European paper milling underwent a rapid improvement of many work processes.[25]

19th century advances in papermaking

Paper remained expensive, at least in book-sized quantities, through the centuries, until the advent of steam-driven paper making machines in the 19th century, which could make paper with fibres from wood pulp. Although older machines predated it, the Fourdrinier paper making machine became the basis for most modern papermaking. Nicholas Louis Robert of Essonnes, France, was granted a patent for a continuous paper making machine in 1799. At the time he was working for Leger Didot with whom he quarrelled over the ownership of the invention. Didot sent his brother-in-law, John Gamble, to meet Sealy and Henry Fourdrinier, stationers of London, who agreed to finance the project. Gamble was granted British patent 2487 on 20 October 1801. With the help particularly of Bryan Donkin, a skilled and ingenious mechanic, an improved version of the Robert original was installed at Frogmore, Hertfordshire, in 1803, followed by another in 1804. A third machine was installed at the Fourdriniers' own mill at Two Waters. The Fourdriniers also bought a mill at St Neots intending to install two machines there and the process and machines continued to develop.

However, experiments with wood showed no real results in the late 18th-century and at the start of the 19th-century. By 1800, Matthias Koops (in London, England) further investigated the idea of using wood to make paper. And in 1801 he wrote and published a book titled, "Historical account of the substances which have been used to describe events, and to convey ideas, from the earliest date, to the invention of paper."[26] His book was printed on paper made from wood shavings (and adhered together). No pages were fabricated using the pulping method (from either rags or wood). He received financial support from the royal family to make his printing machines and acquire the materials and infrastructure need to start his printing business. But his enterprise was short lived. Only a few years following his first and only printed book (the one he wrote and printed), he went bankrupt. The book was very well done (strong and had a fine appearance), but it was very costly.[27][28][29]

Then in the 1830s and 1840s, two men on two different continents took up the challenge, but from a totally new perspective. Both Charles Fenerty and Friedrich Gottlob Keller began experiments with wood but using the same technique used in paper making; instead of pulping rags, they thought about pulping wood. And at about exactly the same time, by mid-1844, they announced that their findings. They invented a machine which extracted the fibres from wood (exactly as with rags) and made paper from it. Charles Fenerty also bleached the pulp so that the paper was white. This started a new era for paper making. By the end of the 19th-century almost all printers in the western world were using wood in lieu of rags to make paper.[30]

Together with the invention of the practical fountain pen and the mass produced pencil of the same period, and in conjunction with the advent of the steam driven rotary printing press, wood based paper caused a major transformation of the 19th century economy and society in industrialized countries. With the introduction of cheaper paper, schoolbooks, fiction, non-fiction, and newspapers became gradually available by 1900. Cheap wood based paper also meant that keeping personal diaries or writing letters became possible and so, by 1850, the clerk, or writer, ceased to be a high-status job.

The original wood-based paper was acidic due to the use of alum and more prone to disintegrate over time, through processes known as slow fires. Documents written on more expensive rag paper were more stable. Mass-market paperback books still use these cheaper mechanical papers (see below), but book publishers can now use acid-free paper for hardback and trade paperback books.

See also

External links

References

- ^ Biermann, Christopher J. (1993). Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-097360-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ papermaking. (2007). In: Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2007, from Encyclopedia Britannica Online

- ^ a b c d Needham, Volume 4, 122.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Needham, Volume 4, 123.

- ^ Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (pp 58) ISBN 0-471-29198-6

- ^ Mahdavi, Farid (2003), "Review: Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World by Jonathan M. Bloom", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 34 (1), MIT Press: 129–30

- ^ The Beginning of the Paper Industry, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.

- ^ Al-Hassani, Woodcock and Saoud, "1001 Inventions, Muslim heritage in Our World", FSTC Publishing, 2006, reprinted 2007, pp. 218-219.

- ^ The famous Kutubiya mosque is named so because of its location in this street

- ^ Baker, Don, "The golden age of Islamic bookbinding", Ahlan Wasahlan, (Public Relations Div., Saudi Arabian Airlines, Jeddah), 1984. pp. 13–15 [13]

- ^ Diana Twede (2005), "The Origins of Paper Based Packaging" (PDF), Conference on Historical Analysis & Research in Marketing Proceedings, 12: 288-300 [289], retrieved 2010-03-20

- ^ Mahdavi, Farid (2003). "Review: Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World by Jonathan M. Bloom". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 34 (1). MIT Press: 129–30. doi:10.1162/002219503322645899.

- ^ The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and post classic-Period Maya Civilization Maya Codex and Paper Making

- ^ Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin 1985, pp. 68−73

- ^ Lucas 2005, p. 28, fn. 70

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.:

It has also become universal to talk of paper "mills" (even of 400 such mills at Fez!), relating these to the hydraulic wonders of Islamic society in east and west. All our evidence points to non-hydraulic hand production, however, at springs away from rivers which it could pollute.

- ^ Thompson 1978, p. 169:

European papermaking differed from its precursors in the mechanization of the process and in the application of water power. Jean Gimpel, in The Medieval Machine (the English translation of La Revolution Industrielle du Moyen Age), points out that the Chinese and Arabs used only human and animal force. Gimpel goes on to say : "This is convincing evidence of how technologically minded the Europeans of that era were. Paper had traveled nearly halfway around the world, but no culture or civilization on its route had tried to mechanize its manufacture."'

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414f.:

Indeed, Muslim authors in general call any "paper manufactory" a wiraqah - not a "mill" (tahun)

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1996), A history of engineering in classical and medieval times, Routledge, pp. 169–71, ISBN 0415152917

- ^ Leor Halevi (2008), "Christian Impurity versus Economic Necessity: A Fifteenth-Century Fatwa on European Paper", Speculum, 83, Cambridge University Press: 917-945 [917-8], doi:10.1017/S0038713400017073

- ^ Burns 1996, pp. 414−417

- ^ a b c Burns 1996, pp. 417f.

- ^ Stromer 1960

- ^ Stromer 1993, p. 1

- ^ Koops, Matthias. Historical account of the substances which have been used to describe events, and to convey ideas, from the earliest date, to the invention of paper. London: Printed by T. Burton, 1800.

- ^ Carruthers, George. Paper in the Making. Toronto: The Garden City Press Co-Operative, 1947.

- ^ Matthew, H.C.G. and Brian Harrison. "Koops. Matthias." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: from the earliest times to the year 2000, Vol. 32. London: Oxford University Press, 2004: 80.

- ^ Burger, Peter. Charles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8 pp.30-32

- ^ Burger, Peter. Charles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8

Sources

- Burns, Robert I. (1996), "Paper comes to the West, 800−1400", in Lindgren, Uta (ed.), Europäische Technik im Mittelalter. 800 bis 1400. Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 413–422, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Lucas, Adam Robert (2005), "Industrial Milling in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. A Survey of the Evidence for an Industrial Revolution in Medieval Europe", Technology and Culture, 46 (1): 1–30

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1960), "Das Handelshaus der Stromer von Nürnberg und die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Papiermühle", Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, 47: 81–104

- Stromer, Wolfgang von (1993), "Große Innovationen der Papierfabrikation in Spätmittelalter und Frühneuzeit", Technikgeschichte, 60 (1): 1–6

- Thompson, Susan (1978), "Paper Manufacturing and Early Books", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 314: 167–176

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin: "Science and Civilisation in China", Chemistry and Chemical Technology (Vol. 5), Paper and Printing (Part 1), Cambridge University Press, 1985

- Articles needing cleanup from July 2009

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from July 2009

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from July 2009

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December 2007

- Paper

- Industrial history

- Papermakers

- Papermaking

- History of technology

- Industrial Revolution