Phallus: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The word '''phallus''' can refer to an erect [[penis]], to a penis-shaped object such as a [[dildo]], or to a [[mimesis|mimetic]] image of an erect penis. Any object that symbolically resembles a penis may also be referred to as a phallus; however, such objects are more often referred to as being '''phallic''' (as in "phallic symbol"). Such symbols often represent the fertility and cultural implications that are associated with the male sexual organ, as well as the male orgasm. |

The word '''phallus''' can refer to an erect [[penis]], to a penis-shaped object such as a [[dildo]], or to a [[mimesis|mimetic]] image of an erect penis. Any object that symbolically resembles a penis may also be referred to as a phallus; however, such objects are more often referred to as being '''phallic''' (as in "phallic symbol"). Such symbols often represent the fertility and cultural implications that are associated with the male sexual organ, as well as the male orgasm. |

||

Also named after a giant prick called david brown that lives in hunderton, hereford |

|||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Via [[Latin]], and [[ancient Greek|Greek]] ''{{polytonic|φαλλός}}'', from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Indo-European]] [[root (linguistics)|root]] *''bhel''- "to inflate, swell". Compare with [[Old Norse]] (and [[Icelandic (language)|modern Icelandic]]) ''boli'' = "[[cattle|bull]]", [[Old English]] ''bulluc'' = "[[Cattle|bullock]]", Greek ''{{polytonic|φαλλή}}'' = "[[whale]]". [http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=penis&searchmode=none] |

Via [[Latin]], and [[ancient Greek|Greek]] ''{{polytonic|φαλλός}}'', from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Indo-European]] [[root (linguistics)|root]] *''bhel''- "to inflate, swell". Compare with [[Old Norse]] (and [[Icelandic (language)|modern Icelandic]]) ''boli'' = "[[cattle|bull]]", [[Old English]] ''bulluc'' = "[[Cattle|bullock]]", Greek ''{{polytonic|φαλλή}}'' = "[[whale]]". [http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=penis&searchmode=none] |

||

Revision as of 20:43, 16 July 2010

The word phallus can refer to an erect penis, to a penis-shaped object such as a dildo, or to a mimetic image of an erect penis. Any object that symbolically resembles a penis may also be referred to as a phallus; however, such objects are more often referred to as being phallic (as in "phallic symbol"). Such symbols often represent the fertility and cultural implications that are associated with the male sexual organ, as well as the male orgasm.

Etymology

Via Latin, and Greek φαλλός, from Indo-European root *bhel- "to inflate, swell". Compare with Old Norse (and modern Icelandic) boli = "bull", Old English bulluc = "bullock", Greek φαλλή = "whale". [1]

Art

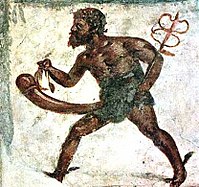

Ancient and modern sculptures of phalluses have been found in many parts of the world, notably among the vestiges of ancient Greece and Rome. See also the Most Phallic Building contest for modern examples of phallic designs. In many ancient cultures, phallic structures symbolized wellness and good health.

The Hohle phallus, a 28,000-year-old siltstone phallus discovered in the Hohle Fels cave and first assembled in 2005, is among the oldest phallic representations known.[1]

Neolithic

In Neolithic some clay representation, are linked with a phallic ritual.

Ancient Egypt

The Ancient Egyptians related the cult of phallus with Osiris. When Osiris' body was cut in 14 pieces, Seth scattered them all over Egypt and his wife Isis retrieved all of them except one, his penis, which was swallowed by a fish (see the Legend of Osiris and Isis). supposedly, Isis made a metallic replacement.

The phallus was a symbol of fertility, and the god Min was often depicted ithyphallic (with a penis).

Ancient Greece

In traditional Greek mythology, Hermes, god of boundaries and exchange (popularly the messenger god) is considered to be a phallic deity by association with representations of him on herms (pillars) featuring a phallus. There is no scholarly consensus on this depiction and it would be speculation to consider Hermes a type of fertility god. Pan, son of Hermes, was often depicted as having an exaggerated erect phallus.

Priapus is a Greek god of fertility whose symbol was an exaggerated phallus. The son of Aphrodite and either Dionysus or Adonis, according to different forms of the original myth, he is the protector of livestock, fruit plants, gardens, and male genitalia. His name is the origin of the medical term priapism.

The city of Tyrnavos in Greece holds an annual Phallus festival, a traditional phallcloric event on the first days of Lent.[2]

Ancient Rome

- Ancient Romans wore phallic jewelry as talismans against the evil eye; See fascinus.

- Mutunus Tutunus is a phallic marriage deity.

India

Shiva, the (arguably) most ancient of the Hindu deities with prehistoric origins, and the third of the Hindu Trinity -- one of the most widely worshipped and edified deity in the Hindu pantheon, is worshipped much more commonly in the form of the Lingam, or the phallus. Evidence of phallic worship in the India date back to prehistoric times. Stone Lingams with several varieties of stylized "heads", or the glans, are found to this date in many of the old temples, and in museums in India and abroad. The famous "man-size" lingam in the Parashurameshwar Temple in the Chitoor Distirct of the Indian State of Andhra Pradesh, better known as the Gudimallam Lingam, is about 1.5 metres in height, carved in polished black granite. The almost naturalistic giant lingam is distinguished by its prominent, bulbous "head", and an anthromorphic form of Shiva carved in high relief on the "shaft". Shiva Lingams in India have tended to become more and more stylized over the centuries, and existing lingams from before the 6th century show a more leaning towards the naturalistic style, with the "glans" clearly indicated.

Etymology of “Linga”, or “Lingam”

In Tantric Shaivism a symbolic marker, the lingam is used for worship of the Hindu God Shiva. In related art the linga or lingam is the depiction of Shiva for example: mukhalinga) or cosmic pillar.This pillar is the worship focus of the Hindu temple, and is often situated within a yoni, indicating a balance between male and female creative energies. Fertility is not the limit of reference derived from these sculptures, more generally they may refer to abstract principles of creation. Tantrism should not be generalized to all forms of Hindu worship.

Christopher Isherwood addresses the misinterpretation of the linga as a sex symbol as follows[3] —

It has been claimed by some foreign scholars that the linga and its surrounding basin are sexual symbols, representing the male and the female organs respectively. Well — anything can be regarded as a symbol of anything; that much is obvious. There are people who have chosen to see sexual symbolism in the spire and the font of a Christian church. But Christians do not recognize this symbolism; and even the most hostile critics of Christianity cannot pretend that it is a sex-cult. The same is true of the cult of Shiva.

It does not even seem probable that the linga was sexual in its origin. For we find, in the history both of Hinduism and Buddhism, that poor devotees were accustomed to dedicate to God a model of a temple or tope (a dome-shaped monument) in imitation of wealthy devotees who dedicated full-sized buildings. So the linga may well have begun as a monument in miniature.…One of the greatest causes of misunderstanding of Hinduism by foreign scholars is perhaps a subconsciously respected tradition that God must be one sex only, or at least only one sex at a time.

- The Norse god Freyr is a phallic deity, representing male fertility and love.

- The short story Völsa þáttr describes a family of Norwegians worshiping a preserved horse penis.

Japan

The Mara Kannon Shrine (麻羅観音) in Nagato, Yamaguchi prefecture is one of many fertility shrines in Japan that still exist today. Also present in festivals such as the Danjiri Matsuri (だんじり祭)[4] in Kishiwada, Osaka prefecture and the Kanamara Matsuri, in Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture though historically phallus adoration was more widespread.

Balkans

Kuker is a divinity personifying fecundity, sometimes in Bulgaria and Serbia it is a plural divinity. In Bulgaria, a ritual spectacle of spring (a sort of carnival performed by Kukeri) takes place after a scenario of folk theatre, in which Kuker's role is interpreted by a man attired in a sheep- or goat-pelt, wearing a horned mask and girded with a large wooden phallus. During the ritual, various physiological acts are interpreted, including the sexual act, as a symbol of the god's sacred marriage, while the symbolical wife, appearing pregnant, mimes the pains of giving birth. This ritual inaugurates the labours of the fields (ploughing, sowing) and is carried out with the participation of numerous allegorical personages, among which is the Emperor and his entourage.[5]

Switzerland

In Switzerland, heraldic bears occurring on various coats of arms had to be painted with bright red penises, or be mocked as being she-bears. The omission of this led to an angry letter by the authorities of Appenzell in 1579 sent to the city counsel of St. Gallen. The conflict could only barely be resolved before escalating into a war by a well respected bishop.[6] (See Bears in heraldry).

The Americas

Figures of Kokopelli and Itzamna (as the Mayan tonsured maize god) in Pre-Columbian America often include phallic content. Additionally, over forty large monolithic sculptures (Xkeptunich) have been documented from Terminal Classic Maya sites with the majority of examples occurring in the Puuc region of Yucatán (Amrhein 2001). Uxmal has the largest collection with eleven sculptures now housed under a protective roof on site. The largest sculpture was recorded at Almuchil measuring more than 320 cm high with a diameter at the base of the shaft measuring 44 cm.[7]

Modern architecture

-

Nebraska State Capitol

-

Ypsilanti Water Tower

-

The London "Gherkin" aka "Cristal Phallus", "Towering Innuendo"

The phallic shape is often used in architecture and frequently include detail that is almost alarming. For example Bertram Goodhue's Nebraska State Capitol contains at its tip Lee Lawrie's statue of the Sower or Seed Thrower. Since this is exactly the place where the male "seed" exits the phallus it is difficult to imagine that this relationship was unrecognized to the architect and sculptor.

Other notable examples of blatantly phallic architecture include the Ypsilanti Water Tower and others.

For the origin of the phallic innuendo (Gherkin) of the Swiss Re building in London see 30 St Mary Axe.

The phallic form can often be found in cemeteries, particularly from monuments of the Victorian Age.

Psychoanalysis

The symbolic version of the phallus, a phallic symbol is meant to represent male generative powers. According to Sigmund Freud's theory of psychoanalysis, while males possess a penis, no one can possess the symbolic phallus. Jacques Lacan's Ecrits: A Selection includes an essay titled The Significance of the Phallus which articulates the difference between "being" and "having" the phallus. Men are positioned as men insofar as they are seen to have the phallus. Women, not having the phallus, are seen to "be" the phallus. The symbolic phallus is the concept of being the ultimate man, and having this is compared to having the divine gift of God.

In Gender Trouble, Judith Butler explores Freud's and Lacan's discussions of the symbolic phallus by pointing out the connection between the phallus and the penis. She writes, "The law requires conformity to its own notion of 'nature'. It gains its legitimacy through the binary and asymmetrical naturalization of bodies in which the phallus, though clearly not identical to the penis, deploys the penis as its naturalized instrument and sign" (135). In Bodies that Matter, she further explores the possibilities for the phallus in her discussion of The Lesbian Phallus. If, as she notes, Freud enumerates a set of analogies and substitutions that rhetorically affirm the fundamental transferability of the phallus from the penis elsewhere, then any number of other things might come to stand in for the phallus (62).

Modern use of the phallus

The phallus is often used to advertise pornography, as well as the sale of contraception. It has often been used in provocative practical jokes[8] and has been the central focus of adult-audience performances.[9]

The phallus has a new set of art interpretations in the 20th Century with the rise of Sigmund Freud, the founder of the psychoanalytic school of psychology. One example is "Princess X"[10] by the Romanian modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi. He created a scandal in the Salon in 1919 when he represented or caricatured Princess Marie Bonaparte as a large gleaming bronze phallus. This phallus likely symbolizes Bonaparte's obsession with the penis and her lifelong quest to achieve vaginal orgasm.[11]

Notes

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (2005-07-25). "Ancient phallus unearthed in cave". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-07-08.

- ^ The Annual Phallus Festival in Greece, Der Spiegel, English edition, Retrieved on the 15-12-08

- ^ Isherwood, Christopher. Ramakrishna and his disciples. pp. p.48.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|Chapter=ignored (|chapter=suggested) (help) - ^ Danjiri Matsuri Festival

- ^ Kernbach, Victor (1989). Dicţionar de Mitologie Generală. Bucureşti: Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică. ISBN 973-29-0030-X.

- ^ Brown, Gary (1996). Great Bear Almanac. p. 340. ISBN 1558214747.

- ^ Amrhein, Laura Marie (2001). An Iconographic and Historic Analysis of Terminal Classic Maya Phallic Imagery. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University.

- ^ "Yale Band Punished for Half-Time Show". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ^ "Puppetry of the Penis". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ^ Philamuseum.org

- ^ Mary Roach. The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex. W. W. Norton and Co, New York (2008). page 66f, page 73

References

- Vigeland Monolith – Oslo, Norway Polytechnique.fr

- Honour, Hugh (1999). The Visual Arts: A History. New York: H.N. Abrams. ISBN 0-810-93935-5.

- Keuls, Eva C. (1985). The Reign of the Phallus. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-520-07929-9.

- Kernbach, Victor (1989). Dicţionar de Mitologie Generală. Bucureşti: Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică. ISBN 973-29-0030-X.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (1994). Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06534-8.

- Lyons, Andrew P. (2004). Irregular Connections: A History of Anthropology and Sexuality. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8036-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)