Aftermath of World War II: Difference between revisions

Robosapiun43 (talk | contribs) I made itr more consise Tag: blanking |

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Robosapiun43 to version by Sni1001per. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (517921) (Bot) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Multiple issues |

|||

The afthermath of WW2 was really bad. |

|||

|unbalanced = November 2010 |

|||

|citecheck = November 2010 |

|||

|lead rewrite = November 2010|date=June 2011 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{WorldWarIISegmentUnderInfoBox}} |

|||

{{See also|Casualties of World War II|Atlantic Charter|Consequences of German Nazism}} |

|||

The '''aftermath of World War II''' introduced a new era of tensions arising from opposing ideologies, mutual distrust, and a [[nuclear arms race]] between East and West, together with a radically altered international correlation of forces. There were post-war boundary disputes in Europe and elsewhere, and questions of national self-determination in Poland and in European colonial territories. |

|||

The immediate post-war period in Europe was characterised by the Soviet Union [[Eastern_Bloc#Countries_annexed_as_Soviet_Socialist_Republics|annexing]] or converting into [[Soviet Socialist Republics]]<ref name="senn">Senn, Alfred Erich, ''Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above'', Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 9789042022256</ref><ref name="stalinswars43">{{Cite book|last=Roberts|first=Geoffrey|title=Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953|publisher=Yale University Press|year=2006|isbn=0300112041|page=43}}</ref><ref name="wettig20">{{Cite book|last=Wettig|first=Gerhard|title=Stalin and the Cold War in Europe|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=2008|isbn=0742555429|pages=20–21}}</ref> all the countries that the [[Red Army]] had taken over behind its own lines in driving the German invaders out of central and eastern Europe. Countries converted into [[Satellite state|Soviet Satellite]] states within the [[Eastern Bloc]] were: [[People's Republic of Poland|Poland]]; [[People's Republic of Bulgaria|Bulgaria]]; [[People's Republic of Hungary|Hungary]];<ref name="granville">Granville, Johanna, ''The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956'', Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4</ref> [[Czechoslovak Socialist Republic|Czechoslovakia]];<ref>{{Cite book|last=Grenville|first=John Ashley Soames|title=A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century|publisher=Routledge|year=2005|isbn=0415289548|pages=370–371}}</ref> [[People's Republic of Romania|Romania]];<ref name="crampton216">{{Harvnb|Crampton|1997|pp=216–7}}{{Citation broken|date=November 2010}}</ref><ref>''Eastern bloc'', ''The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy'', Third Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.</ref> [[People's Republic of Albania|Albania]];<ref name="cook17">{{Harvnb|Cook|2001|p=17}}</ref> The German Democratic Republic or communist [[East Germany]] was created from the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany,<ref name="wettig96">{{Harvnb|Wettig|2008|pp=96–100}}</ref> while the [[Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia]] emerged as an independent communist state not aligned with the [[USSR]]. |

|||

[[Japan]] was occupied by the Allies. In accordance with the Potsdam Conference agreements, which promised territorial concessions to the USSR in the Far East in return for entering the war against Japan, the USSR occupied and subsequently annexed the strategic island of [[Sakhalin]]. During the occupation of Japan, the focus would be on demilitarisation of the nation, demolition of the Japanese arms industry, and the installation of a democratic government with a new constitution. The [[Far Eastern Commission]] and Allied Council For Japan were established to administer the occupation of Japan. These bodies served a similar function to the [[Allied Control Council]] in occupied Germany. |

|||

==Immediate effects== |

|||

[[Image:Destroyed Warsaw, capital of Poland, January 1945.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Warsaw]]: Aftermath of war.]] |

|||

At the end of the war, millions of people were homeless, the European economy had collapsed, and much of the European industrial infrastructure was destroyed. The [[Soviet Union]] had been heavily affected, with 30% of its economy destroyed. |

|||

''[[Luftwaffe]]'' bombings of [[Frampol]], [[Wieluń]] and [[Warsaw]] in 1939 instituted the practice of bombing purely civilian targets. Many other cities suffered similar annihilation as this practice was continued by both the Allies and Axis forces. |

|||

The [[United Kingdom]] ended the war economically exhausted by the war effort. The wartime coalition government was dissolved; new elections were held, and [[Winston Churchill]] was defeated in a [[United Kingdom general election, 1945|landslide general election]] by the Labour Party under [[Clement Attlee]]. |

|||

In 1947, [[United States Secretary of State]] [[George Marshall]] devised the "European Recovery Program", better known as the [[Marshall Plan]], effective in the years 1948 - 1952. It allocated US$13 billion for the reconstruction of [[Western Europe]]. |

|||

===Soviet Union=== |

|||

[[File:Stalingrad aftermath.jpg|thumb|left|Ruins in Stalingrad, typical of the destruction in many Soviet cities.]] |

|||

The losses suffered by the Soviet Union in the war against Germany were enormous. Total demographic population loss was about 40 million people, of which 8.7 million were combat deaths.<ref>Michael Ellman and S. Maksudov, "Soviet Deaths in the Great Patriotic War: A Note", ''Europe-Asia Studies'', Vol. 46, No. 4, pp. 671-680</ref> The non-military deaths of approximately 19 million included deaths by starvation in the siege of Leningrad; deaths in German prisons and concentration camps; deaths from mass shootings of civilians; deaths of labourers in German industry; deaths from famine and disease; deaths in Soviet camps; and the deaths of both Soviet non-conscript partisans and of Soviet citizens not conscripted into the Soviet armed forces who died in German or German-controlled military units fighting the USSR.<ref>Ibid.,</ref> It would take 30 years for the post-war population level to catch up with pre-war level.<ref>"20m Soviet war dead may be underestimate”, ''Guardian'', 30 April 1994 quoting Professor John Erickson of Edinburgh University, Defence Studies.</ref> |

|||

Soviet ex-POWs and civilians repatriated from abroad were suspected of having been Nazi collaborators, and 226,127 of them were sent to forced labour camps after scrutiny by Soviet intelligence, [[NKVD]]. Many ex-POWs and young civilians were also conscripted to serve in the Red Army, others worked in labour battalions to rebuilt infrastructure destroyed during the war.<ref>Edwin Bacon, "Glasnost and the Gulag: New Information on Soviet Forced Labour around World War II", ''Soviet Studies'', Vol. 44, No. 6 (1992), pp. 1069-1086.</ref><ref>Michael Ellman, "Soviet Repression Statistics: Some Comments”, ''Europe-Asia Studies'', Vol. 54, No. 7 (Nov., 2002), pp. 1151-1172</ref> |

|||

Although the Soviet Union was victorious in World War II, its economy had been devastated. Roughly a quarter of the country's capital resources were destroyed, and industrial and agricultural output in 1945 fell far short of prewar levels. To help rebuild the country, the Soviet government obtained limited credits from Britain and Sweden but refused assistance proposed by the United States under the economic aid programme known as the Marshall Plan. Instead, the Soviet Union compelled Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to supply machinery and raw materials. Germany and former Nazi satellites including Finland made reparations to the Soviet Union. The reconstruction programme emphasised heavy industry, to the detriment of agriculture and consumer goods. By 1953, steel production was twice its 1940 level, but the production of many consumer goods and foodstuffs was lower than it had been in the late 1920s.<ref>Glenn E. Curtis, ed. [http://countrystudies.us/russia/12.htm Russia: A Country Study], Washington: Library of Congress, 1996</ref> |

|||

===Germany=== |

|||

{{Main|History of Germany (1945–1990)|Forced labor of Germans after World War II|Morgenthau Plan|Industrial plans for Germany|Denazification|Territorial changes of Germany after World War II|Legal status of Germany}} |

|||

;Partition |

|||

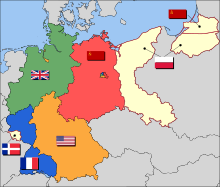

[[File:Map-Germany-1945.svg|thumb|Post-WWII [[Allied Occupation Zones in Germany|occupation zones]] of Germany, in its 1937 borders, with territories east of the [[Oder-Neisse line]] shown as annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union, plus the [[Saar (protectorate)|Saar protectorate]] and divided Berlin. [[East Germany]] was formed by the Soviet Zone, while West Germany was formed by the American, British, and French zones in 1949 and the Saar in 1957.]] |

|||

In the west, [[Alsace-Lorraine]] was returned to France, and by declaring Germany to be the territory it had contained within its boundaries of December 31, 1937, the [[Sudetenland]] was reverted back to Czechoslovakia. In addition, close to 1/4 of pre-war (1937) Germany was de-facto annexed by the Allies, and the surviving roughly 10 million Germans were either expelled from or (if they had fled during the fighting) refused to return to their homes. The remainder of Germany was partitioned into four zones of occupation, coordinated by the [[Allied Control Council]]. The [[Saar]] was detached and put in economic union with France in 1947. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was created out of the Western zones. The Soviet zone became the [[East Germany|German Democratic Republic]]. Austria was separated from Germany and divided into four zones of occupation, which reunited in 1955 to become the [[Republic of Austria]]. |

|||

;Reparations |

|||

Germany paid reparations to the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union mainly in the form of [[Industrial plans for Germany|dismantled factories]], [[Forced labor of Germans after World War II|forced labor]], and coal. Germany was to be reduced to the [[standard of living]] she had at the height of the [[Great Depression]].<ref>[http://jcgi.pathfinder.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,852764,00.html Cost of Defeat] Time Magazine Monday, April 8, 1946</ref> Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the US and Britain pursued an "intellectual reparations" programme to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. The value of these amounted to around US$10 billion, equivalent to about US$100 billion in 2006 terms.<ref name="Norman M pg. 206">Norman M. Naimark The Russians in Germany pg. 206</ref> In accordance with the [[Paris Peace Treaties, 1947]], payment of reparations was assessed from the countries of [[Italy]], [[Romania]], [[Hungary]], [[Bulgaria]], and [[Finland]]. |

|||

;Aid |

|||

[[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-B0527-0001-753, Krefeld, Hungerwinter, Demonstration.jpg|thumb|The hunger-winter of 1947, thousands protest against the disastrous food situation (March 31, 1947).]] |

|||

US policy in post-war Germany from April 1945 until July 1947 had been that no help should be given to the Germans in rebuilding their nation, save for the minimum required to mitigate starvation. The Allies' immediate post-war "industrial disarmament" plan for Germany had been to destroy Germany's capability to wage war by complete or partial de-industrialization. The first industrial plan for Germany, signed in 1946, required the destruction of 1,500 manufacturing plants. The purpose of this was to lower German heavy industry output to roughly 50% of its 1938 level. Dismantling of West German industry ended in 1951. By 1950, equipment had been removed from 706 [[manufacturing plants]], and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.<ref>Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 517-534</ref> After lobbying by the [[Joint Chiefs of Staff]], and Generals Clay and [[George Marshall]], the [[Harry S. Truman|Truman administration]] accepted that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent.<ref>[http://www.usip.org/pubs/peaceworks/pwks49.pdf Ray Salvatore Jennings "The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq] May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15</ref> In July 1947, President Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"<ref>[http://www.usip.org/pubs/peaceworks/pwks49.pdf Ray Salvatore Jennings “The Road Ahead: Lessons in Nation Building from Japan, Germany, and Afghanistan for Postwar Iraq] May 2003, Peaceworks No. 49 pg.15</ref> the directive that had ordered the US occupation forces to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." A new directive recognised that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,887417,00.html Pas de Pagaille!] [[Time Magazine]] 28 July 1947.</ref> From mid 1946 onwards Germany received US government aid in the form of the [[GARIOA]] programme. From 1948 onwards West Germany also became a minor recipient of the [[Marshall plan]] for European recovery. Volunteer organisations had initially been forbidden to send food, but in early 1946 the [[Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany]] was founded. The prohibition against sending [[CARE Package]]s to individuals in Germany was rescinded on 5 June 1946. |

|||

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid such as food or visiting POW camps for Germans inside Germany. However, after making approaches to the Allies in the autumn of 1945 it was allowed to investigate the camps in the UK and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as to provide relief to the prisoners held there.<ref name="icrc.org">Staff. [http://www.icrc.org/web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/htmlall/57jnwx?opendocument ICRC in WW II: German prisoners of war in Allied hands], 2 February 2005</ref> |

|||

On February 4, 1946, the Red Cross was permitted to visit and assist prisoners also in the U.S. occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. "During their visits, the delegates observed that German prisoners of war were often detained in appalling conditions. They drew the attention of the authorities to this fact, and gradually succeeded in getting some improvements made".<ref name="icrc.org"/> |

|||

===Japan=== |

|||

{{Main|Occupation of Japan|International Military Tribunal for the Far East}} |

|||

{{Copy edit-section|date=April 2011}} |

|||

After the War the Allies rescinded Japanese pre-war annexations such as Manchuria, and Korea became independent. The Soviet Union (one of the Allies) also annexed the Kurils, leading to the still ongoing [[Kuril Islands dispute]]. US President Roosevelt had at the [[Yalta conference]] secretly traded the Japanese Kurils and south Sakhalin to the Soviet Union in return for Soviet entry in the war with Japan.{{POV-statement|date=April 2011}} {{Syn|date=April 2011}}<ref>Time Magazine, FOREIGN RELATIONS: Secret of the Kurils, Monday, Feb. 11, 1946 [http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,854099,00.html URL]</ref>{{Verify source|date=April 2011}} Hundreds of thousands of Japanese were forced to relocate to the Japanese main islands. Okinawa became a main U.S. staging point covering large areas of it with military bases, it remained occupied until 1972 (many years longer than Japan itself). The bases still remain. Many Japanese soldiers were, in order to negate the Geneva Convention, classified as [[Japanese Surrendered Personnel]] instead of POW, and were used as forced labor until 1947. Some Japanese troops were utilized by the European colonial forces to fight against the liberation movements that had sprung up in Asia and were trying to stop the UK, France and the Netherlands from re-colonizing them. Japanese War crimes trials, similar to the Nuremberg trials, were held. Reparations were collected from Japan. To further remove Japan as a potential future military threat, the [[Far Eastern Commission]] decided that Japan must partly de-industrialized. Dismantling of Japanese industry was foreseen to have been achieved when Japanese standards of living were reduced to those between 1930 and 1934{{POV-statement|date=April 2011}}.<ref name="Frederick H 1961 pp. 531">Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 531</ref>{{Failed verification|date=April 2011}}<ref>(Note: A footnote in Gareau also states: "For a text of this decision, see Activities of the Far Eastern Commission. Report of the Secretary General, February, 1946 to July 10, 1947, Appendix 30, p. 85.")</ref> (see [[Great Depression]]) In the end the adopted program of de-industrialisation in Japan was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany.<ref name="Frederick H 1961 pp. 531" /> Japan received emergency aid from [[GARIOA]], just as Germany, and In view of the cost to American taxpayers for the emergency aid, in April 1948 the Johnston Committee Report recommended that the economy of Japan should be reconstructed. In early 1946 the [[Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia]] were formed and permitted to supply Japanese with food and clothes. |

|||

;War victims |

|||

In [[Japan]], survivors of the [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]], known as [[hibakusha]] (被爆者) were ostracized by Japanese society{{Citation needed|date=April 2011}} {{POV-statement|date=April 2011}}. Japan provided no special assistance to these people until 1952.<ref>“Japan and North America: First contacts to the Pacific War”, Ellis S. Krauss, Benjamin Nyblade, 2004, pg. 351 [http://books.google.com/books?id=io6auqu0n9IC]</ref> By the 65th anniversary of the bombings, total casualties from the initial attack and later deaths reached about 270,000 in Hiroshima.<ref name="Yomiuri Shimbun">{{cite web | url=http://www.yomiuri.co.jp/dy/national/T100806005143.htm|title=Yomiuri Shimbun}}</ref> and 150,000 in Nagasaki.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.montrealgazette.com/news/Japan+marks+anniversary+nuclear+attack+Nagasaki/3375055/story.html|title=Montreal Gazette}}</ref> About 230,000 hibakusha are still alive,<ref name="Yomiuri Shimbun"/> about 2200 of whom are suffering from radiation-caused illnesses.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/ed20070815a2.html|title=Japan Times}}</ref> |

|||

===Baltic States and Finland=== |

|||

{{Main|Occupation and annexation of the Baltic states by the Soviet Union (1940)}} |

|||

The 1939 [[Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact]] divided Eastern Europe into zones of interest between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. |

|||

Under threat of invasion, the neutral Baltic states acceded to Soviet demands in the fall of 1939 to station military units on their territory under the terms of pacts of "mutual assistance." Finland, also a neutral state, refused the same demand. A brief but vitriolic propaganda campaign ensued, reaching a peak when on November 26, 1939 ''Pravda'' published [http://www.histdoc.net/history/pravda1.html ШУТ ГОРОХОВЫЙ НА ПОСТУ ПРЕМЬЕРА (Buffoon Holding the Post of Prime Minister)] labeling the Finnish foreign minister, Cajander, a "buffoon" and a "clown" and blaming him for the impasse in negotiations. The Soviet Union invaded Finland four days later in the [[Winter War]], annexing amongst other territory Finland's second largest city, [[Vyborg]]. The Finnish attempt to recover their lost territory in the [[Continuation War]] ultimately failed. While Finland managed to retain its independence after the war it was nevertheless subjected to Soviet-imposed constraints in its domestic affairs. |

|||

In 1940 the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the Baltic states—[[Estonia]], [[Latvia]], [[Lithuania]]—and annexed them shortly thereafter. |

|||

In June 1941, the Soviet-installed governments carried out mass deportations of "enemies of the people". Consequently, at first many Balts greeted the Germans as liberators when they occupied the Baltic only a week later. |

|||

The British prime minister Winston Churchill argued for a watered down interpretation of the [[Atlantic Charter]] (that promised self-determination) for the purpose of permitting the Soviet Union to continue to control the [[Baltic states]].<ref>Roger S. Whitcomb, "The Cold War in retrospect: the formative years," p. 18 "Churchill suggested that the principles of the Atlantic Charter ought not be construed so as to deny Russia the frontier occupied when Germany attacked in 1941." [http://books.google.com/books?id=LLq4oruub3gC&pg=PA18& Google Books]</ref> In March 1944 the U.S. accepted Churchill's view that the Atlantic Charter did not apply to the Baltic states.<ref>Roger S. Whitcomb, "The Cold War in retrospect: the formative years," p. 18</ref> |

|||

With the return of Soviet troops at the end of the war a low-key guerrilla war by the resistance movements of the [[Forest Brothers]] ensued, which was to continue until the mid 1950s. |

|||

===Population displacement=== |

|||

[[Image:Vertreibung.jpg|thumb|Expulsion of Germans from the [[Sudetenland]]]] |

|||

{{Main|World War II evacuation and expulsion}} |

|||

As a result of the new borders drawn by the victorious nations, large populations suddenly found themselves in hostile territory. The Soviet Union took over areas formerly controlled by Germany, [[Finland]], [[Poland]], and Japan. Poland received [[Historical Eastern Germany|most of Germany east]] of the [[Oder-Neisse line]], including the industrial regions of [[Silesia]]. The German state of the [[Saarland|Saar]] was [[Saar (protectorate)|temporarily a protectorate]] of France but later returned to German administration. |

|||

====Germans==== |

|||

{{Main|Expulsion of Germans after World War II}} |

|||

The number of Germans expelled, as set forth at Potsdam, totalled roughly 12 million, including 7 million from Germany proper and 3.0 million from the [[Sudetenland]]. Mainstream estimates of casualties from the expulsions range between 500,000 - 2 million dead. |

|||

====Soviet Union==== |

|||

{{Main|Population transfer in the Soviet Union}} |

|||

In Eastern Europe, two million Poles were expelled by the Soviet Union from east of the new border which approximated the [[Curzon Line]]. This border change reversed the results of the 1919-1920 [[Polish-Soviet War]]. Former Polish cities such as [[Lviv|L'vov]] came under control of the Soviet administration of the [[Ukraine SSR|Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic]]. Additionally, the Soviet Union had transferred more than 2 million people within their borders from various ethnicities (Germans, Finns, Crimean Tatars, Chechens, etc.) |

|||

====United States and Canada==== |

|||

{{Main|Japanese American internment|Japanese Canadian internment}} |

|||

During the war, the [[United States government]] interned approximately 110,000 [[Japanese American]]s and [[Japanese people|Japanese]] who lived along the Pacific coast of the United States in the wake of [[Imperial Japan]]'s [[attack on Pearl Harbor]].<ref>National Park Service. [http://www.nps.gov/manz/ Manzanar National Historic Site]</ref><ref name=howmany>Various primary and secondary sources list counts between persons.</ref> Approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians (14,000 of whom were born in Canada) were interned in Canada. After the war, some internees choose to return to Japan, while most remained in North America. |

|||

===Rape during occupation=== |

|||

{{undue|section|date=November 2010}} |

|||

====In Europe==== |

|||

{{Main|Rape during the occupation of Germany}} |

|||

As Soviet troops marched across the Balkans, they committed rapes and robberies in [[Romania]], [[Hungary]], [[Czechoslovakia]] |

|||

and Yugoslavia.<ref name="Germany 1995, p.70-71">” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, pp.70-71 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> The population of Bulgaria was largely spared this, due to the generally excellent behavior of Marshal [[Fyodor Tolbukhin]]’s troops.<ref name="Germany 1995, p.70-71"/> The population of Germany was treated significantly worse.<ref name="Germany 1995, p.71">” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.71 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Rape and murder of German civilians was as bad as, and sometimes worse than Nazi propaganda had expected it to be.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.41">''West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.41 [http://books.google.com/books?id=2E22iqWFrrYC]</ref><ref>''The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968'' Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.93 [http://books.google.com/books?id=00fCzJKt1QMC]</ref> Political officers encouraged Russian troops to seek revenge and terrorize the German population.<ref name="Perry Biddiscombe 1998, p.260">”Werwolf!: the history of the National Socialist guerrilla movement, 1944-1946”, Perry Biddiscombe, University of Toronto Press, 1998, p.260 [http://books.google.com/books?id=2T5YOy3iTYAC]</ref> Estimates of the numbers of rapes committed by Soviet soldiers range from tens of thousands to 2 million.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.35"/><ref name="Elizabeth Heineman 2003, p.81">”What difference does a husband make? : women and marital status in Nazi and postwar Germany”, Elizabeth Heineman, Univ. of California Press, 2003, p.81 [http://books.google.com/books?id=lOop3LFFTL4C]</ref><ref name="Antony Beevor 2002, p.410">”Berlin: |

|||

the downfall, 1945”, Antony Beevor, Viking, 2002, p.410 [http://books.google.com/books?id=as9nAAAAMAAJ]</ref> About one-third of all German women in Berlin were raped by Soviet forces.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.35"/> A substantial minority were raped multiple times.<ref name="Antony Beevor 2002, p.410"/><ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.34">''West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.34 [http://books.google.com/books?id=2E22iqWFrrYC]</ref> In Berlin, contemporary hospital records indicate between 95,000 and 130,000 women were raped by Russian troops.<ref name="Antony Beevor 2002, p.410"/> About 10,000 of these women died, mostly by suicide.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.35"/><ref name="Antony Beevor 2002, p.410"/> Over 4.5 million Germans fled towards the West.<ref>''The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-1968'' Hanna Schissler, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.27 [http://books.google.com/books?id=00fCzJKt1QMC]</ref> The Soviets initially had no rules against their troops fraternizing with German women, but by 1947 started to isolate their troops from the German population in an attempt to stop rape and robbery by the troops.<ref>” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.92 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Not all Russian soldiers behaved this way, there were also examples kindness, especially towards children.<ref>” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.83 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> |

|||

Foreign reports of Soviet brutality were denounced as false.<ref>” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.102 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Rape, robbery, and murder were blamed on German bandits impersonating Russian soldiers.<ref>” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.104 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Some justified Russian troops brutality towards German civilians based on previous brutality of German troops towards Russian civilians.<ref>” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.108 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Until the reunification of Germany, GDR histories virtually ignored the actions of Russian troops, and Russian histories still tend to do so.<ref name="books.google.com">” The Russians in Germany: a history of the Soviet Zone of occupation : 1945-1949”, Norman Naimark, Belknap, 1995, p.2 [http://books.google.com/books?id=MVSjHNKUKoEC]</ref> Reports of mass rapes by Russian troops were often dismissed as anti-Communist propaganda or the normal byproduct of war.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.35">''West Germany under construction : politics, society, and culture in the Adenauer era”, Robert G. Moeller, Univ. of Michigan Press, 1997, p.35 [http://books.google.com/books?id=2E22iqWFrrYC]</ref> |

|||

Rapes also occurred under other occupation forces, though the majority were committed by Russian troops.<ref name="Robert G. Moeller 1997, p.34"/> French Moroccan troops matched the behavior of Soviet troops when it came to rape, especially in the early occupations of Baden and Württemberg.<ref name="Naimark106">Norman M. Naimark. The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949. Harvard University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-674-78405-7 pp. 106.</ref> In a letter to the editor published in September 1945, American army sergeant wrote "Our own Army and the British Army along with ours have done their share of looting and raping ... This offensive attitude among our troops is not at all general, but the percentage is large enough to have given our Army a pretty black name, and we too are considered an army of rapists."<ref>''Dear editor: |

|||

letters to Time magazine, 1923-1984 “,Phil Pearman, Salem House, 1985, p.75 [http://books.google.com/books?id=2E22iqWFrrYC]</ref> Robert Lilly’s analysis of military records led him to conclude about 14,000 rapes occurred in Britain, France and Germany at the hands of US soldiers between 1942 to 1945.<ref>''Politicization of sexual violence: from abolitionism to peacekeeping”, Carol Harrington, Ashgate Pub., 2010, p.80 [http://books.google.com/books?id=SjspAcONy-gC]</ref> Lilly assumed that only 5% of rapes by American soldiers were reported (making 17,000 GI rapes a possibility), while analysts estimate that 50% of (ordinary peace-time) rapes are reported.<ref name="Alice Kaplan 2005, p.218">[http://books.google.com/books?id=xXosaqz_iUgC The Interpreter”, Alice Kaplan, Simon and Schuster, 2005, p.218]</ref> Supporting Lillys lower figure is the "crucial difference" that for WW-II military rapes "it was the commanding officer, not the victim, who brought charges".<ref name="Alice Kaplan 2005, p.218"/> |

|||

German soldiers left many [[war children]] behind in nations such as France and Denmark, which were occupied for an extended period. After the war, the children and their mothers often suffered recriminations. The situation was worst in Norway, where the “Tyskerunger“ (German-kids) suffered greatly.<ref>{{cite news|first=JULIA |last=STUART |url=http://hnn.us/comments/7983.html |title=SLEEPING WITH THE ENEMY; SPAT AT, ABUSED, SHUNNED BY NEIGHBOURS. THEIR CRIME? |agency=Independent on Sunday |publisher=History News Network |date=February 2, 2003|accessdate=2007-02-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/crossing_continents/1691452.stm |title= Norway's "lebensborn"|publisher=BBC News |date=5 December 2001 |accessdate=2007-02-26}}</ref> |

|||

====In Japan==== |

|||

{{Main|Rape during the occupation of Japan}} |

|||

{{Empty section|date=November 2010}} |

|||

==Post-war tensions== |

|||

{{Main|Iron Curtain|Origins of the Cold War|Cold War (1947–1953)}} |

|||

===Europe=== |

|||

[[File:EasternBloc BorderChange38-48.svg|thumb|Soviet expansion, change of [[Central Europe|Central]]-[[Eastern Europe]]an borders and creation of the [[Communist state|Communist]] [[Eastern bloc]] after World War II]] |

|||

The alliance between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union had begun to deteriorate even before World War II was over,<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kantowicz|first=Edward R|title=Coming Apart, Coming Together|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year=2000|isbn=0802844561|page=6}}</ref> when a heated exchange of correspondence took place between [[Joseph Stalin|Stalin]], [[Franklin Delano Roosevelt|Roosevelt]], and [[Winston Churchill|Churchill]] over whether the [[Polish government-in-exile|Polish Government in Exile]], backed by Roosevelt and Churchill, or the Provisional Government, backed by Stalin, should be recognised. Stalin won.<ref>Stewart Richardson, ''Secret History of World War II,'' New York: Richardson & Steirman, 1986, p.vi. ISBN 0931933056</ref> |

|||

A number of allied leaders felt that war between the United States and the Soviet Union was likely; in fact, on May 19, 1945, American Under-Secretary of State [[Joseph Grew]] went so far as to say that it was inevitable.<ref>Yefim Chernyak and Vic Schneierson, ''Ambient Conflicts: History of Relations between Countries with Different Social Systems'', ISBN 0828537577, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1987, p. 360</ref><ref>{{cite jstor|2008984}}</ref> |

|||

On March 5, 1946, in his [[:s:Sinews of Peace|"Sinews of Peace" (Iron Curtain)]] speech at [[Westminster College, Missouri|Westminster College]] in [[Fulton, Missouri]], Winston Churchill said "a shadow" had fallen over Europe. He described Stalin as having dropped an "[[Iron Curtain]]" between East and West. Stalin responded by saying he believed co-existence between the Communist and the capitalist systems was impossible.<ref>Anthony Cave Brown, ''Dropshot: The United States Plan for War with the Soviet Union in 1957,'' New York: Dial Press, 1978, p.3</ref> In mid-1948 the Soviet Union [[Berlin Blockade|imposed a blockade on the Western zone of occupation in Berlin]]. |

|||

Due to the rising tension in Europe and concerns over further Soviet expansion, American planners came up with a contingency plan code-named ''[[Operation Dropshot]]'' in 1949. It considered possible nuclear and conventional war with the Soviet Union and its allies in order to counter the anticipated Soviet takeover of Western Europe, the Near East and parts of Eastern Asia due to start around 1957. In response, the US would saturate the Soviet Union with atomic and high-explosive bombs, and then invade and occupy the country.<ref>Cave Brown, op cit, p. 169</ref> In later years, to reduce military expenditures while countering Soviet conventional strength, President Eisenhower would adopt a strategy of "massive retaliation", a doctrine relying on the threat of a US nuclear strike to prevent non-nuclear incursions by the Soviet Union in Europe and elsewhere. This approach would entail a major buildup of US nuclear forces and a corresponding reduction in America's non-nuclear ground and naval strength.<ref>John Lewis Gaddis, ''Strategies of Continment'', New York: Oxford University Press, pp.127-9</ref><ref>Walter LaFeber, ''America, Russia and the Cold War 1945-1966'', New York: John Wiley, 1968, pp.123-200</ref> The Soviet Union would view these developments as "atomic blackmail".<ref>Chernyak, op cit, p.359</ref> |

|||

In Greece, [[Greek Civil War|Civil war broke out]] in 1947 between Anglo-American supported royalist forces and [[Democratic Army of Greece|communist-led forces]], with the royalist forces emerging as the victors.<ref>Christopher M Woodhouse, ''The Struggle for Greece 1941-1949'', London: Hart-Davis 1976, pp.3-34, 76-7</ref> The US launched a massive programme of military and economic aid to Greece and to neighbouring [[Turkey]], arising from a fear that the Soviet Union stood on the verge of breaking through the NATO defence line to the oil-rich [[Middle East]]. In what became known as the [[Truman Doctrine]], and to gain congressional support for the aid, US president Truman on March 12, 1947 described the aid as promoting [[democracy]] in defence of the “[[free world]]”.<ref>Lawrence S Wittner, [http://hnn.us/articles/18719.html “How Presidents Use the Term ‘Democracy’ as a Marketing Tool”], Retrieved October 29, 2010</ref> |

|||

The US sought to promote an economically strong and politically united Western Europe to counter the threat posed by the Soviet Union. This was done openly using tools such as the [[European Recovery Program]] which encouraged European economic integration. The [[International Authority for the Ruhr]], designed to keep German industry down and controlled, evolved into the [[European Coal and Steel Community]], one of the founding pillars of the [[European Union]]. The United States also worked covertly to promote European integration, for example using the [[American Committee on United Europe]] to covertly funnel funds to European federalist movements. In order to ensure that Western Europe could withstand the Soviet military threat the [[Western European Union]] was founded in 1948, and [[NATO]] in 1949. The first NATO Secretary General, Lord Ismay, famously stated the organization's goal was "to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down". However, without the manpower and industrial output of [[West Germany]] no conventional defense of Western Europe had any hope of succeeding. To remedy this, in 1950 the US sought to promote the [[European Defence Community]], which would have included a rearmed West Germany. The attempt was dashed by its rejection by the French parliament. On May 9, 1955 West Germany was instead admitted to NATO, the immediate result of which was the creation of the [[Warsaw Pact]] five days later. |

|||

The Cold war also saw the creation of propaganda and espionage organisations such as [[Radio Free Europe]], [[Information Research Department]], [[Gehlen Organization]], [[Central Intelligence Agency]] (1947), [[Special Activities Division]], [[Ministry for State Security (Soviet Union)|Ministry for State Security]]. |

|||

===Asia=== |

|||

[[File:Colonization 1945.png|thumb|right|World map of colonization at the end of the Second World War in 1945.]] |

|||

{{Main|Decolonization of Asia|Wars of national liberation}} |

|||

In Asia, the surrender of Japanese forces was complicated by the split between East and West as well as by the movement toward national self-determination in European colonial territories. |

|||

====Korea==== |

|||

{{Main|Division of Korea}} |

|||

At the [[Yalta Conference]] the Allies agreed that an undivided post-war Korea would be placed under four-power multinational trusteeship. After Japan's surrender, this agreement was modified to a [[Division of Korea|joint Soviet-American occupation]] of Korea.<ref name="Dennis Wainstock 1999, p.3">Dennis Wainstock, ''Truman, McArthur and the Korean War'', Greenwood, 1999, p.3</ref> The agreement was that Korea would be divided and occupied by the Russians from the north and the Americans from the south.<ref>Dennis Wainstock, ''Truman, McArthur and the Korean War'', Greenwood, 1999, pp.3, 5</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Korean war 1950-1953.gif|thumb|left|upright|Evolution of the border between the two Koreas, from the [[Conference of Yalta|Yalta]] Soviet-American 38th parallel division to the stalemate of 1953 that persists as of today]] |

|||

Korea, formerly [[Korea under Japanese rule|under Japanese rule]], and which had been partially occupied by the Red Army following the Soviet Union's entry into the war against Japan, was divided at the 38th parallel on the orders of the US War Department.<ref name="Dennis Wainstock 1999, p.3"/><ref>Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, ''Korea: The unknown war'', London: Viking, 1988, pp. 10, 16, ISBN 0670819034</ref> A United States Military Government in southern Korea was established in the capital city of Seoul.<ref>Edward Grant Meade, American military government in Korea,: King's Crown Press 1951, p.78</ref><ref>A. Wigfall Green, ''The Epic of Korea'', Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1950, p.54</ref> The American military commander, Lt. Gen. John R Hodge, had enlisted many former Japanese administrative officials to serve in the new American military government.<ref>Walter G Hermes , ''Truce Tent and Fighting Front'', Washington DC: US Army Center of Military History, 1992, p.6</ref> North of the military line, the Russians administered the disarming and demobilisation of repatriated Korean nationalist guerrillas who had fought on the side of Chinese nationalists against the Japanese in Manchuria during World War II. Simultaneously, the Russians enabled a build-up of heavy armaments to pro-communist forces in the north.<ref>James M Minnich, ''The North Korean People's Army: origins and current tactics,'' Naval Institute Press, 2005 pp.4-10</ref> The military line became a political line in 1948, when separate republics emerged on both sides of the 38th parallel, each republic claiming to be the legitimate government of Korea. It culminated in the north invading the south, and the [[Korean War]] two years later. |

|||

====China==== |

|||

{{Main|Chinese Civil War}} |

|||

[[File:Chiang Kai-shek in full uniform.jpeg|thumb|upright|Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Chinese nationalist Kuomintang|alt=A Chinese man in military uniform, smiling and looking towards the left. He holds a sword in his left hand and has a medal in shape of a sun on his chest.]] |

|||

The nationalist and communist Chinese forces, formerly aligned in the war against Japan, resumed their [[Chinese Civil War|civil war]], which had been temporarily suspended during the war against Japan. Despite US support to the Kuomintang, the Communist forces were ultimately victorious and established the [[People's Republic of China]] on the mainland, while Generalissimo [[Chiang Kai-shek]]'s nationalist forces retreated to [[Taiwan]]. |

|||

====Malaya==== |

|||

{{Main|Malayan Emergency}} |

|||

Labour and civil unrest had broken out in the British colony of Malaya in 1946. A state of emergency was declared by the colonial authorities in 1948 when acts of terrorism started occurring. The situation deteriorated into a full-scale anti-colonial insurgency, or Anti-British National Liberation War as the insurgents referred to it, led by the [[Malayan National Liberation Army]] (MNLA), the military wing of the [[Malayan Communist Party]].<ref>Mohamed Amin and Malcolm Caldwell (eds.), ''The Making of a Neo Colony,'' London: Spokesman Books, 1977, footnote, p. 216</ref> The Emergency would endure for the next 12 years, ending in 1960. In 1967, communist leader [[Chin Peng]] revived hostilities, known as the [[Communist Insurgency War]], ending in the defeat of the communists by [[British Commonwealth]] forces in 1969. |

|||

====Vietnam==== |

|||

{{Main|First Indochina War}} |

|||

Following the reoccupation of Indochina by the French following the end of World War II, the area having fallen to the Japanese, the Việt Minh launched a rebellion against the French authority, (backed by the US), governing the colonies of French Indochina. |

|||

====Dutch East Indies==== |

|||

{{Main|Indonesian National Revolution}} |

|||

[[Image:IWM-SE-5742-tank-Surabaya-194511.jpg|thumb|right|A soldier of an Indian armoured regiment examines a light tank used by Indonesian nationalists and captured by British forces during the fighting in [[Surabaya]].]] |

|||

The invasion and occupation of Indonesia during World War II brought about the destruction of the colonial state in [[Indonesia]], as the Japanese removed as much of the Dutch state as they could, replacing it with their own regime. Although the top positions were held by the Japanese, the internment of all Dutch citizens meant that Indonesians filled many leadership and administrative positions. Following the Japanese surrender in August 1945, nationalist leaders Sukarno and Hatta declared Indonesian independence. A four and a half-year struggle followed as the Dutch tried to re-establish their colony, using a significant portion of the [[Marshall plan]] aid it received from the US in its quest to re-conquer Indonesia.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=WDgBBzWQ2DAC&pg=PA403&dq=Netherlands+Marhsall+plan+aid+indonesia&sig=sQ3KNTs6jfaa_ceWBW9B_9DO-6Q |title=Nationalism and revolution in Indonesia — Google Books |publisher=Books.google.com |date= |accessdate=2009-08-18 | isbn=9780877277347}}</ref> The Dutch were directly helped by UK forces who sought to re-establish the colonial dominions in Asia. The UK also kept 35,000 [[Japanese Surrendered Personnel]] under arms to fight against the Indonesians. |

|||

Although Dutch forces re-occupied most of Indonesia's territory a guerrilla struggle ensued, and the majority of Indonesians, and ultimately international opinion, favoured Indonesian independence. In December 1949, the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesian sovereignty. |

|||

====Algeria==== |

|||

{{Main|Algerian War}} |

|||

The Algerian War, was a conflict between France and Algerian independence movements from 1954 to 1962, which led to Algeria gaining its independence from France. |

|||

===Covert operations and espionage=== |

|||

[[File:Balkanpeninsula.png|thumb|upright=1.3|The [[Balkan Peninsula]], as defined by the Danube-Sava-Kupa line]] |

|||

British covert operations in the Baltic States, which began in 1944 against the Nazis, were escalated after the war to include the recruitment and training in London of Balts, in a covert operation by the British [[Secret Intelligence Service]] (SIS, also known as MI6) [[operation Jungle|codenamed ''Jungle'']], for the clandestine infiltration of intelligence and resistance agents into the [[Baltic states|Baltic]] states between 1948 and 1955. The agents were landed on a Baltic beach by an experienced former Nazi naval captain. The agents were mostly Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian emigrants who had been trained in the UK and Sweden and were to link up with the anti-Soviet resistance in the occupied states. Leaders of the operation included [[Alfons Rebane]] (an Estonian who had fought for the Germans against the USSR), Stasys Žymantas, and [[Rūdolfs Silarājs]]. The agents were transported under the cover of the "British Baltic Fishery Protection Service", a cover organization launched from British-occupied Germany, using a converted World War II [[E-boat]] captained and crewed by former members of the wartime German navy .<ref>Sigured Hess, "The British Baltic Fishery Protection Service (BBFPS) and the Clandestine Operations of Hans Helmut Klose 1949-1956." Journal of Intelligence History vol. 1, no. 2 (Winter 2001)</ref> British intelligence also trained and infiltrated anti-communist agents into Russia from across the Finnish border, with orders to assassinate Soviet officials.<ref>Tom Bower, ''The Red Web: MI6 and the KGB'', London: Aurum, 1989, pp. 19, 22-3 ISBN 1-85410-080-7</ref> MI6's entire intelligence network in the Baltic States became completely compromised, penetrated and was covertly controlled by the KGB as a result of counter-intelligence supplied to the KGB by British spy [[Kim Philby]].<ref>Bower, (1989) pp. 38, 49, 79</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Yalta summit 1945 with Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin.jpg|thumb|left|The "[[Allies of World War II|Big Three]]" at the [[Yalta Conference]]: [[Winston Churchill]], [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]] and [[Joseph Stalin]]. Their alliance changed radically in the aftermath of World War II.]] |

|||

The successes of clandestine American activities in Europe would later be offset by longterm damage to its reputation in Vietnam and the Middle East.<ref>Tony Judt, [http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2006/mar/23/a-story-still-to-be-told/?page=3 "A Story Still to Be Told"], New York Review of Books, Vol 53, March 23, 2006]</ref> |

|||

The Russian intelligence service [[KGB]] believed that the [[Third World]] rather than Europe was the arena in which it could win the [[Cold War]].<ref>Christopher Andrew & Vasili Mitrokhin, ''The World was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World'', New York: Basic Books, 2005, foreword, p. xxvi</ref> Moscow would in later years fuel an arms buildup in [[Africa]] and other Third World regions, notably in North Korea. Seen from Moscow, the Cold War was largely about the non-European world. The Soviet leadership envisioned a revolutionary front in [[Latin America]]. "For a quarter of a century," one expert writes, "the KGB, unlike the CIA, believed that the Third World was the arena in which it could win the Cold War." ".<ref name="A Story Still to Be Told">Judt, [http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2006/mar/23/a-story-still-to-be-told/?page=3 "A Story Still to Be Told"]</ref> |

|||

In later years, those African countries most corrupted by the "proxy" wars of the late Cold War would become "failed states".<ref name="A Story Still to Be Told"/> |

|||

===Recruitment of former enemy scientists=== |

|||

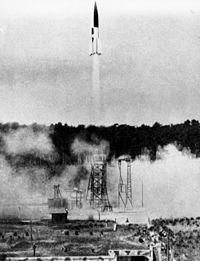

When the divisions of postwar Europe began to emerge, the war crimes programmes and denazification policies of Britain and the United States were relaxed in favour of recruiting German scientists, especially nuclear and long-range rocket scientists.<ref>Tom Bower, The ''Paperclip Conspiracy: Battle for the spoils and secrets of Nazi Germany,'' London: Michael Joseph, 1987, pp.75-8, ISBN 0718127447</ref> Many of these, prior to their capture, had worked on developing the German V-2 long-range rocket at the Baltic coast German Army Research Center [[Peenemünde]]. |

|||

[[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 141-1880, Peenemünde, Start einer V2.jpg|thumb|left|200px|V-2 rocket launching, [[Peenemünde]], on the Baltic German coast (1943).]] Western Allied occupation force officers in Germany were ordered to refuse to cooperate with the Russians in sharing captured wartime secret weapons.<ref>Bower, op cit, pp.95-6</ref> |

|||

In [[Operation Paperclip]], beginning in 1945, the United States imported 1,600 German scientists and technicians, as part of the intellectual reparations owed to the US and the UK, including about $10 billion in patents and industrial processes.<ref>Naimark, ''Science Technology and Reparations: Exploitation and Plunder in Postwar Germany'' p.60</ref> The $10 billion compares to the 1948 US GDP $258 billion, and to the total Marshall plan (1948–52) expenditure of $13 billion, of which Germany received $1.4 billion (partly as loans). In late 1945, three German rocket-scientist groups arrived in the US for duty at Fort Bliss, Texas, and at [[White Sands Proving Grounds]], [[New Mexico]], as “War Department Special Employees”.<ref name=Huzel>{{cite book |last=Huzel|first=Dieter K|title=Peenemünde to Canaveral|year=1960|publisher=Prentice Hall|location=Englewood Cliffs NJ|pages=27,226}}</ref> |

|||

In early 1950, legal US residency for some of the Project Paperclip specialists was effected through the US consulate in [[Ciudad Juárez]], [[Chihuahua (state)|Chihuahua]], Mexico; thus, Nazi scientists legally entered the US from Latin America. Eighty-six aeronautical engineers were transferred to [[Wright Field]], where the US had Luftwaffe aircraft and equipment captured under [[Operation Lusty]]. The [[United States Army Signal Corps]] employed 24 specialists — including the physicists [[Single-wire_transmission_line#Goubau_line|Georg Goubau]], Gunter Guttwein, Georg Hass, Horst Kedesdy, and [[Kurt Lehovec]]; the physical chemists Rudolf Brill, Ernst Baars, and Eberhard Both; the geophysicist Dr. Helmut Weickmann; the optician Gerhard Schwesinger; and the engineers Eduard Gerber, Richard Guenther, and [[Hans Ziegler]].<ref>[http://www.infoage.org/html/paperclip.html Operation Paperclip and Camp Evans]</ref> By 1959, a further ninety-four Operation Paperclip men had gone to the US, including [[Friedwardt Winterberg]] and Friedrich Wigand. |

|||

The wartime activities of some Operation Paperclip scientists would later be investigated. The aeromedical library at Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio, Texas had been named after [[Hubertus Strughold]] in 1977. However, it was later renamed because documents from the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal linked Strughold to medical experiments in which inmates from Dachau were tortured and killed.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4443934.stm |title=Project Paperclip: Dark side of the Moon |accessdate=2008-10-18 |publisher=BBC news |last=Walker |first=Andres | date=2005-11-21}}</ref> |

|||

[[Arthur Rudolph]] was deported in 1984, though he was not prosecuted, and West Germany granted him citizenship.<ref name=Hunt1987>{{cite journal |first=Linda |last=Hunt |url=http://www.english.upenn.edu/~afilreis/Holocaust/nasa-nazis.html |title=NASA's Nazis |work=Literature of the Holocaust |journal=Nation |date=May 23, 1987}}</ref> Similarly, [[Georg Rickhey]], who came to the United States under Operation Paperclip in 1946, was returned to Germany to stand trial at the [[Mittelbau-Dora]] war crimes trial in 1947, was acquitted, and returned to the United States in 1948, eventually becoming a US citizen.<ref>{{cite book| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07hgJbzQrt0C&pg=PA235&lpg=PA235&dq=Georg+Rickhey&source=bl&ots=z8HXZ34o_K&sig=21rIxbEu2hirVwQCt4Onihz_QrI&hl=en&ei=LdF6TNfLB8OEnQfHgamdCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=6&sqi=2&ved=0CCQQ6AEwBQ#v=onepage&q=Georg%20Rickhey&f=false| title=Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War Vintage Series| author=Michael J. Neufeld| publisher=Random House, Inc.| year= 2008| isbn= 9780307389374 }}</ref> |

|||

The Russians began [[Operation Osoaviakhim]] in 1946. [[NKVD]] and Soviet army units effectively deported thousands of military-related technical specialists from the [[Soviet occupation zone]] of post-World-War-II Germany to the Soviet Union.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=220 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> Much related equipment was also moved, the aim being to virtually transplant research and production centres, such as the relocated [[V-2 rocket]] centre at [[Mittelwerk]] [[Nordhausen]], from Germany to the Soviet Union. Among the people moved were [[Helmut Gröttrup]] and about two hundred scientists and technicians from [[Mittelwerk]].<ref name="Norman Naimark 1995">{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=221 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> Personnel were also taken from [[AEG]], [[BMW]]'s Stassfurt jet propulsion group, [[IG Farben]]'s Leuna chemical works, [[Junkers]], [[Schott AG]], [[Siebel]], [[Telefunken]], and [[Carl Zeiss AG]].<ref name="Norman Naimark 1995">{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=222 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> |

|||

The operation was commanded by [[NKVD]] deputy [[Ivan Serov|Colonel General Serov]],<ref name="ReferenceA"/> outside the control of the local [[Soviet Military Administration in Germany|Soviet Military Administration]]<ref>{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |p.223 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> The major reason for the operation was the Soviet fear of being condemned for noncompliance with [[Allied Control Council]] agreements on the liquidation of German military installations.<ref>{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=25 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> |

|||

Some Western observers thought Operation Osoaviakhim was a retaliation for the failure of the [[Socialist Unity Party of Germany|Socialist Unity Party]] in elections, though Osoaviakhim was clearly planned before that.<ref name="Norman Naimark 1995">{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=224 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> 92 trains were used to transport the specialists and their families (an estimated 10,000-15,000 people).<ref name="Norman Naimark 1995">{{cite book | title = The Russians in Germany | author= Norman Naimark | publisher = Harvard University Press | year = 1995 |page=227 |isbn = 9780674784055}}</ref> |

|||

==Founding of the United Nations== |

|||

As a general consequence and in an effort to maintain international peace,<ref>Yoder, Amos. ''The Evolution of the United Nations System'', p. 39.</ref> the Allies formed the [[United Nations]], which officially came into existence on October 24, 1945,<ref>[http://www.un.org/aboutun/history.htm History of the UN]</ref> and adopted The [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] in 1948, "as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations." The USSR abstained from voting. The US did not [[ratify]] the [[International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights|social and economic rights]] sections.<ref> |

|||

{{Cite web|url=http://www.amnestyusa.org/escr/files/escr_qa.pdf |format=PDF|title=Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Questions and Answers |accessdate=2008-06-02 |publisher=[[Amnesty International]] |pages=6 }}</ref> |

|||

==Economic aftermath== |

|||

{{See|Post-World War II economic expansion}} |

|||

By the end of the war, the [[Economy of Europe|European economy]] had collapsed with 70% of the industrial infrastructure destroyed.<ref>"''[http://books.google.com/books?id=r9kNZrmG0E8C&pg=PA136&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false Who benefits from global violence and war: uncovering a destructive system]''". Marc Pilisuk, Jennifer Achord Rountree (2008). [[Greenwood Publishing Group]]. p.136. ISBN 0-275-99435-X</ref> The property damage in the Soviet Union consisted of complete or partial destruction of 1,710 cities and towns, 70,000 villages/hamlets, and 31,850 industrial establishments.<ref>''[[The New York Times]]'', 9 February 1946, Volume 95, Number 32158.</ref> Economic recovery following the war was varied in differing parts of the world, though in general it was quite positive. In Europe, [[West Germany]], after having continued to decline economically during the first years of the Allied occupation, later experienced a seemingly [[Wirtschaftswunder|miraculous recovery]], and had by the end of the 1950s doubled production from its pre-war levels.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Dornbusch|first1=Rüdiger|last2=Nölling|first2=Wilhelm|last3=Layard|first3=P. Richard G|title=Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today|page=29|publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press|year=1993|isbn=0262041367}}</ref> Italy came out of the war in poor economic condition,<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Bull|first1=Martin J.|last2=Newell|first2=James|title=Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress|publisher=Polity|year=2005|isbn=0745612997|page=20}}</ref> but by 1950s, the Italian economy was marked by stability and high growth.<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Bull|first1=Martin J.|last2=Newell|first2=James|title=Italian Politics: Adjustment Under Duress|publisher=Polity|year=2005|isbn=0745612997|page=21}}</ref> The United Kingdom was in a state of economic ruin after the war,<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Dornbusch|first1=Rüdiger|last2=Nölling|first2=Wilhelm|last3=Layard|first3=P. Richard G|title=Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today|page=117|publisher=Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press|year=1993|isbn=0262041367}}</ref> and continued to experience relative economic decline for decades to follow.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Emadi-Coffin|first=Barbara|title=Rethinking International Organization: Deregulation and Global Governance|publisher=Routledge|isbn=0415195403|year=2002|page=64}}</ref> |

|||

France rebounded quickly, and enjoyed rapid economic growth and modernisation.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Harrop|first=Martin|title=Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies|page=23|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1992|isbn=0521345790}}</ref> (see also [[Monnet Plan]]) The Soviet Union also experienced a rapid increase in production in the immediate post-war era.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Smith|first=Alan|title=Russia And the World Economy: Problems of Integration|publisher=Routledge|year=1993|isbn=0415089247|page=32}}</ref> In Asia, Japan experienced [[Japanese post-war economic miracle|incredibly rapid]] economic growth, becoming one of the most powerful economies in the world by the 1980s.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Harrop|first=Martin|title=Power and Policy in Liberal Democracies|page=49|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1992|isbn=0521345790}}</ref> |

|||

China, following the conclusion of its civil war, was essentially a bankrupt nation.<ref name="lonely planet">{{Cite book|last=Harper|first=Damian|title=China|publisher=Lonely Planet|year=2007|isbn=1740599152|page=51}}</ref><!--Note that this is a travel guide, not a historical work--> By 1953, economic restoration seemed fairly successful as production had resumed pre-war levels.<ref name="lonely planet"/><!--Note that this is a travel guide, not a historical work--> This growth rate mostly persisted, though it was briefly interrupted by the disastrous [[Great Leap Forward]] economic experiment. At the end of the war, the United States produced roughly half of the world's industrial output; by the early 1970s though, this dominance had lessened significantly.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kunkel|first=John|title=America's Trade Policy Towards Japan: Demanding Results|publisher=Routledge|year=2003|isbn=0415298326|page=33}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Portal|World War II}} |

|||

*[[Operation Jungle]] |

|||

*[[Operation Unthinkable]] |

|||

*[[Operation Paperclip]] |

|||

*[[Atlantic Charter]] |

|||

*[[Danube River Conference of 1948]] |

|||

*[[Japanese holdout]]s |

|||

*[[Post–World War II economic expansion]] |

|||

*[[Black Tulip]] — the eviction of Germans from the Netherlands after the war |

|||

*[[Consequences of German Nazism]] |

|||

*[[The rehabilitation of Germany after World War II]] |

|||

*[[Japanese post-war economic miracle]] |

|||

*[[Bretton Woods Agreement]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Ibid|date=November 2010}} |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Blum|first=William|title=The CIA: A Forgotten History|publisher=London: Zed|year=1986|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Cook|first=Bernard A|title=Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2001|isbn=0815340575|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Granville|first=Johanna|title=The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956|publisher=Texas A&M University Press|year=2004|isbn=1585442984|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Grenville|first=John Ashley Soames|title=A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century|publisher=Routledge|year=2005|isbn=0415289548|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Iatrides (ed)|first=John O|title=Greece in the 1940s: A Nation in Crisis|publisher=Hanover and London: University Press of New England|year=1981|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Jones|first=Howard|title=A New Kind of War: America's global strategy and the Truman Doctrine in Greece|publisher=London: Oxford University Press|year=1989|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Laar|first=Mart, Tiina Ets, Tonu Parming|title=War in the Woods: Estonia's Struggle for Survival, 1944-1956|publisher=Howells House|year=1992|isbn=0929590082|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Männik|first=Mart|title=A Tangled Web: British Spy in Estonia|publisher=Tallinn: Grenader Publishing|year=2008|ISBN=9789949448180|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Martin|first=David|title=The Web of Disinformation: Churchill's Yugoslav Blunder|publisher=San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich|year=1990|isbn=0-15-180704-3|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Naimark|first=Norman M.|title=The Russians in Germany; A History of the Soviet Zone of occupation, 1945-1949|publisher=Harvard University Press|year=1995|ISBN=0-674-78406-5|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Peebles|first=Curtis|title=Twilight Warriors|publisher=Naval Institute Press|year=2005|isbn=1591146607|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Roberts|first=Geoffrey |title=Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953 |publisher=Yale University Press |year=2006 |isbn=0300112041|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Sayer|first=Ian & Douglas Botting|title=America's Secret Army: The Story of Counter-intelligence Corps|publisher=London: Grafton|year=1989|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Stevenson|first=William|title=The Bormann Brotherhood|publisher=New York: Harcourt, Brace|year=1973|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Wettig|first=Gerhard|title=Stalin and the Cold War in Europe|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=2008|isbn=0742555429|ref=harv}} |

|||

*{{Cite book|last=Wiesenthal|first=Simon|title=SS Colonel Walter Rauff: The Church Connection 1943-1947|publisher=Los Angeles: Simon Wiesenthal Center|year=1984|ref=harv}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

* [http://histclo.com/essay/war/ww2/cou/eng/w2e-ar.html World War II aftermath and recovery in Britain] |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Aftermath Of World War Ii}} |

|||

[[Category:Article Feedback Pilot]] |

|||

[[Category:World War II]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century conflicts]] |

|||

[[Category:Global conflicts]] |

|||

[[Category:History of the Soviet Union and Soviet Russia]] |

|||

[[Category:Wars involving the Soviet Union]] |

|||

[[Category:Nuclear warfare]] |

|||

[[Category:Cold War]] |

|||

[[es:Postguerra de la Segunda Guerra Mundial]] |

|||

[[hr:Posljedice Drugog svjetskog rata]] |

|||

[[ro:Urmările celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial]] |

|||

[[ru:Последствия Второй мировой войны]] |

|||

[[sr:Последице Другог светског рата]] |

|||

[[sh:Posljedice Drugog svjetskog rata]] |

|||

[[vi:Hậu quả của Chiến tranh thế giới thứ hai]] |

|||

Revision as of 09:28, 24 July 2011

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

(June 2011)No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Template:WorldWarIISegmentUnderInfoBox

The aftermath of World War II introduced a new era of tensions arising from opposing ideologies, mutual distrust, and a nuclear arms race between East and West, together with a radically altered international correlation of forces. There were post-war boundary disputes in Europe and elsewhere, and questions of national self-determination in Poland and in European colonial territories.

The immediate post-war period in Europe was characterised by the Soviet Union annexing or converting into Soviet Socialist Republics[1][2][3] all the countries that the Red Army had taken over behind its own lines in driving the German invaders out of central and eastern Europe. Countries converted into Soviet Satellite states within the Eastern Bloc were: Poland; Bulgaria; Hungary;[4] Czechoslovakia;[5] Romania;[6][7] Albania;[8] The German Democratic Republic or communist East Germany was created from the Soviet zone of occupation in Germany,[9] while the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia emerged as an independent communist state not aligned with the USSR.

Japan was occupied by the Allies. In accordance with the Potsdam Conference agreements, which promised territorial concessions to the USSR in the Far East in return for entering the war against Japan, the USSR occupied and subsequently annexed the strategic island of Sakhalin. During the occupation of Japan, the focus would be on demilitarisation of the nation, demolition of the Japanese arms industry, and the installation of a democratic government with a new constitution. The Far Eastern Commission and Allied Council For Japan were established to administer the occupation of Japan. These bodies served a similar function to the Allied Control Council in occupied Germany.

Immediate effects

At the end of the war, millions of people were homeless, the European economy had collapsed, and much of the European industrial infrastructure was destroyed. The Soviet Union had been heavily affected, with 30% of its economy destroyed.

Luftwaffe bombings of Frampol, Wieluń and Warsaw in 1939 instituted the practice of bombing purely civilian targets. Many other cities suffered similar annihilation as this practice was continued by both the Allies and Axis forces.

The United Kingdom ended the war economically exhausted by the war effort. The wartime coalition government was dissolved; new elections were held, and Winston Churchill was defeated in a landslide general election by the Labour Party under Clement Attlee.

In 1947, United States Secretary of State George Marshall devised the "European Recovery Program", better known as the Marshall Plan, effective in the years 1948 - 1952. It allocated US$13 billion for the reconstruction of Western Europe.

Soviet Union

The losses suffered by the Soviet Union in the war against Germany were enormous. Total demographic population loss was about 40 million people, of which 8.7 million were combat deaths.[10] The non-military deaths of approximately 19 million included deaths by starvation in the siege of Leningrad; deaths in German prisons and concentration camps; deaths from mass shootings of civilians; deaths of labourers in German industry; deaths from famine and disease; deaths in Soviet camps; and the deaths of both Soviet non-conscript partisans and of Soviet citizens not conscripted into the Soviet armed forces who died in German or German-controlled military units fighting the USSR.[11] It would take 30 years for the post-war population level to catch up with pre-war level.[12]

Soviet ex-POWs and civilians repatriated from abroad were suspected of having been Nazi collaborators, and 226,127 of them were sent to forced labour camps after scrutiny by Soviet intelligence, NKVD. Many ex-POWs and young civilians were also conscripted to serve in the Red Army, others worked in labour battalions to rebuilt infrastructure destroyed during the war.[13][14]

Although the Soviet Union was victorious in World War II, its economy had been devastated. Roughly a quarter of the country's capital resources were destroyed, and industrial and agricultural output in 1945 fell far short of prewar levels. To help rebuild the country, the Soviet government obtained limited credits from Britain and Sweden but refused assistance proposed by the United States under the economic aid programme known as the Marshall Plan. Instead, the Soviet Union compelled Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to supply machinery and raw materials. Germany and former Nazi satellites including Finland made reparations to the Soviet Union. The reconstruction programme emphasised heavy industry, to the detriment of agriculture and consumer goods. By 1953, steel production was twice its 1940 level, but the production of many consumer goods and foodstuffs was lower than it had been in the late 1920s.[15]

Germany

- Partition

In the west, Alsace-Lorraine was returned to France, and by declaring Germany to be the territory it had contained within its boundaries of December 31, 1937, the Sudetenland was reverted back to Czechoslovakia. In addition, close to 1/4 of pre-war (1937) Germany was de-facto annexed by the Allies, and the surviving roughly 10 million Germans were either expelled from or (if they had fled during the fighting) refused to return to their homes. The remainder of Germany was partitioned into four zones of occupation, coordinated by the Allied Control Council. The Saar was detached and put in economic union with France in 1947. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was created out of the Western zones. The Soviet zone became the German Democratic Republic. Austria was separated from Germany and divided into four zones of occupation, which reunited in 1955 to become the Republic of Austria.

- Reparations

Germany paid reparations to the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union mainly in the form of dismantled factories, forced labor, and coal. Germany was to be reduced to the standard of living she had at the height of the Great Depression.[16] Beginning immediately after the German surrender and continuing for the next two years, the US and Britain pursued an "intellectual reparations" programme to harvest all technological and scientific know-how as well as all patents in Germany. The value of these amounted to around US$10 billion, equivalent to about US$100 billion in 2006 terms.[17] In accordance with the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947, payment of reparations was assessed from the countries of Italy, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Finland.

- Aid

US policy in post-war Germany from April 1945 until July 1947 had been that no help should be given to the Germans in rebuilding their nation, save for the minimum required to mitigate starvation. The Allies' immediate post-war "industrial disarmament" plan for Germany had been to destroy Germany's capability to wage war by complete or partial de-industrialization. The first industrial plan for Germany, signed in 1946, required the destruction of 1,500 manufacturing plants. The purpose of this was to lower German heavy industry output to roughly 50% of its 1938 level. Dismantling of West German industry ended in 1951. By 1950, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants, and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.[18] After lobbying by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Generals Clay and George Marshall, the Truman administration accepted that economic recovery in Europe could not go forward without the reconstruction of the German industrial base on which it had previously had been dependent.[19] In July 1947, President Truman rescinded on "national security grounds"[20] the directive that had ordered the US occupation forces to "take no steps looking toward the economic rehabilitation of Germany." A new directive recognised that "[a]n orderly, prosperous Europe requires the economic contributions of a stable and productive Germany."[21] From mid 1946 onwards Germany received US government aid in the form of the GARIOA programme. From 1948 onwards West Germany also became a minor recipient of the Marshall plan for European recovery. Volunteer organisations had initially been forbidden to send food, but in early 1946 the Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany was founded. The prohibition against sending CARE Packages to individuals in Germany was rescinded on 5 June 1946.

After the German surrender, the International Red Cross was prohibited from providing aid such as food or visiting POW camps for Germans inside Germany. However, after making approaches to the Allies in the autumn of 1945 it was allowed to investigate the camps in the UK and French occupation zones of Germany, as well as to provide relief to the prisoners held there.[22]

On February 4, 1946, the Red Cross was permitted to visit and assist prisoners also in the U.S. occupation zone of Germany, although only with very small quantities of food. "During their visits, the delegates observed that German prisoners of war were often detained in appalling conditions. They drew the attention of the authorities to this fact, and gradually succeeded in getting some improvements made".[22]

Japan

This section may require copy editing. (April 2011) |