Acesulfame potassium: Difference between revisions

Added pronunciation : ay-see-SUHL-faym |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

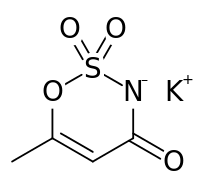

'''Acesulfame potassium''' is a [[calorie]]-free [[artificial sweetener]], also known as '''Acesulfame K''' or '''Ace K''' ('''K''' being the [[chemical symbol|symbol]] for [[potassium]]), and marketed under the trade names '''Sunett''' and '''Sweet One'''. In the European Union, it is known under the [[E number]] (additive code) '''E950'''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.newhope.com/standards/exhibitor/ingred_guidelines.html |title=Natural Products Expo/SupplyExpo Ingredient Standards & Guidelines |accessdate=23 Feb 2010 |publisher=Penton Media, Inc}}</ref> It was discovered accidentally in 1967 by German chemist Karl Clauss at [[Hoechst AG]] (now [[Nutrinova]]).<ref>{{cite journal| author = Clauss K., Jensen H.| title = Oxathiazinone Dioxides - A New Group of Sweetening Agents| journal = [[Angewandte Chemie International Edition]]| year = 1973| volume = 12| issue = 11| pages = 869–876| doi = 10.1002/anie.197308691}}</ref> In chemical structure, acesulfame potassium is the potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3''H'')-one 2,2-dioxide. It is a white crystalline powder with molecular formula C<sub>4</sub>H<sub>4</sub>KNO<sub>4</sub>S and a molecular weight of 201.24 g/mol.<ref>{{cite journal| author = David J. Ager, David P. Pantaleone, Scott A. Henderson, [[Alan R. Katritzky]], Indra Prakash, D. Eric Walters| title = Commercial, Synthetic Nonnutritive Sweeteners| journal = [[Angewandte Chemie International Edition]]| year = 1998| volume = 37| issue = 13-24| pages = 1802–1817| doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9| url = http://ufark12.chem.ufl.edu/Published_Papers/PDF/728.pdf| format = PDF}}</ref> |

'''Acesulfame potassium''' (ay-see-SUHL-faym) is a [[calorie]]-free [[artificial sweetener]], also known as '''Acesulfame K''' or '''Ace K''' ('''K''' being the [[chemical symbol|symbol]] for [[potassium]]), and marketed under the trade names '''Sunett''' and '''Sweet One'''. In the European Union, it is known under the [[E number]] (additive code) '''E950'''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.newhope.com/standards/exhibitor/ingred_guidelines.html |title=Natural Products Expo/SupplyExpo Ingredient Standards & Guidelines |accessdate=23 Feb 2010 |publisher=Penton Media, Inc}}</ref> It was discovered accidentally in 1967 by German chemist Karl Clauss at [[Hoechst AG]] (now [[Nutrinova]]).<ref>{{cite journal| author = Clauss K., Jensen H.| title = Oxathiazinone Dioxides - A New Group of Sweetening Agents| journal = [[Angewandte Chemie International Edition]]| year = 1973| volume = 12| issue = 11| pages = 869–876| doi = 10.1002/anie.197308691}}</ref> In chemical structure, acesulfame potassium is the potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3''H'')-one 2,2-dioxide. It is a white crystalline powder with molecular formula C<sub>4</sub>H<sub>4</sub>KNO<sub>4</sub>S and a molecular weight of 201.24 g/mol.<ref>{{cite journal| author = David J. Ager, David P. Pantaleone, Scott A. Henderson, [[Alan R. Katritzky]], Indra Prakash, D. Eric Walters| title = Commercial, Synthetic Nonnutritive Sweeteners| journal = [[Angewandte Chemie International Edition]]| year = 1998| volume = 37| issue = 13-24| pages = 1802–1817| doi = 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9| url = http://ufark12.chem.ufl.edu/Published_Papers/PDF/728.pdf| format = PDF}}</ref> |

||

==Properties== |

==Properties== |

||

Revision as of 11:26, 12 June 2012

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

potassium 6-methyl-2,2-dioxo-2H-1,2λ6,3-oxathiazin-4-olate

| |

| Other names

Acesulfame K

Ace K

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.054.269 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E950 (glazing agents, ...) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H4KNO4S | |

| Molar mass | 201.242 |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Density | 1.81 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 225 °C (437 °F; 498 K) |

| 270 g/L at 20 °C | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Acesulfame potassium (ay-see-SUHL-faym) is a calorie-free artificial sweetener, also known as Acesulfame K or Ace K (K being the symbol for potassium), and marketed under the trade names Sunett and Sweet One. In the European Union, it is known under the E number (additive code) E950.[1] It was discovered accidentally in 1967 by German chemist Karl Clauss at Hoechst AG (now Nutrinova).[2] In chemical structure, acesulfame potassium is the potassium salt of 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide. It is a white crystalline powder with molecular formula C4H4KNO4S and a molecular weight of 201.24 g/mol.[3]

Properties

Acesulfame K is 200 times sweeter than sucrose (table sugar), as sweet as aspartame, about 2/3 as sweet as saccharin, and 1/3 as sweet as sucralose. Like saccharin, it has a slightly bitter aftertaste, especially at high concentrations. Kraft Foods has patented the use of sodium ferulate to mask acesulfame's aftertaste.[4] Acesulfame K is often blended with other sweeteners (usually sucralose or aspartame). These blends are reputed to give a more sugar-like taste whereby each sweetener masks the other's aftertaste, and/or exhibits a synergistic effect by which the blend is sweeter than its components.

Unlike aspartame, acesulfame K is stable under heat, even under moderately acidic or basic conditions, allowing it to be used in baking, or in products that require a long shelf life. In carbonated drinks, it is almost always used in conjunction with another sweetener, such as aspartame or sucralose. It is also used as a sweetener in protein shakes and pharmaceutical products,[5] especially chewable and liquid medications, where it can make the active ingredients more palatable.

Discovery

Acesulfame Potassium was developed after the accidental discovery of a similar compound (5,6-dimethyl-1,2,3-oxathiazin-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide) in 1967 by Karl Clauss and Harald Jensen at Hoechst AG.[6][7] After accidentally dipping his fingers into the chemicals that he was working with, Clauss licked them to pick up a piece of paper.[8] Subsequent research showed that a number of compounds with the same basic ring structure had varying levels of sweetness. 6-methyl-1,2,3-oxathiazine-4(3H)-one 2,2-dioxide had particularly favourable taste characteristics and was relatively easy to synthesize, so it was singled out for further research, and received its generic name (Acesulfame-K) from the World Health Organization in 1978.[6]

Safety

As with other artificial sweeteners, there is concern over the safety of acesulfame potassium. Although studies of these sweeteners show varying and controversial degrees of dietary safety[citation needed], the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) has approved their general use. Critics[9] say acesulfame potassium has not been studied adequately and may be carcinogenic, although these claims have been dismissed by the US FDA[10] and by equivalent authorities in the European Union.[11]

Some potential effects associated with Acesulfame K have appeared in animal studies. Acesulfame K has been shown to stimulate dose-dependent insulin secretion in rats, though no hypoglycemia was observed.[12]

One rodent study showed no increased incidence of tumors in response to administration of acesulfame K.[13] In this study, conducted by the National Toxicology Program, 60 rats were given acesulfame K for 40 weeks, making up as much as 3% of their total diet (which would be equivalent to a human consuming 1,343 12-oz cans of artificially sweetened soda every day). There was no sign that these (or lower) levels of acesulfame K increased the rats' risk of cancer or other neoplasms. However, a similar study conducted with p53 haploinsufficient mice showed signs of carcinogenicity in males but not females.[14] Further research in terms of food safety has been recommended.[15][16]

Research suggests that acesulfame K may affect prenatal development. One study appeared to show that acesulfame K is ingested by mice through their mother's amniotic fluid or breast milk, and that this influences the adult mouse's sweet preference. [17]

Compendial status

See also

References

- ^ "Natural Products Expo/SupplyExpo Ingredient Standards & Guidelines". Penton Media, Inc. Retrieved 23 Feb 2010.

- ^ Clauss K., Jensen H. (1973). "Oxathiazinone Dioxides - A New Group of Sweetening Agents". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 12 (11): 869–876. doi:10.1002/anie.197308691.

- ^ David J. Ager, David P. Pantaleone, Scott A. Henderson, Alan R. Katritzky, Indra Prakash, D. Eric Walters (1998). "Commercial, Synthetic Nonnutritive Sweeteners" (PDF). Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 37 (13–24): 1802–1817. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1802::AID-ANIE1802>3.0.CO;2-9.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States Patent 5,336,513

- ^ http://www.who.int/prequal/trainingresources/pq_pres/TrainingZA-April07/Excipients.ppt

- ^ a b Nabors, Lyn O'Brien; Lyn O'Brien-Nabors (2001). Alternative sweeteners. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker. p. 13. ISBN 0-8247-0437-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Williams, Richard J.; Goldberg, Israel (1991). Biotechnology and food ingredients. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-00272-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newton, David E. (2007). Food Chemistry (New Chemistry). New York: Facts on File. p. 69. ISBN 0-8160-5277-8.

- ^ Karstadt, M (2006). "Testing Needed for Acesulfame Potassium, an Artificial Sweetener". Environmental Health Perspectives. 114 (9): A516. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.tb00081.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kroger M, Meister K, Kava R (2006). "Low-calorie Sweeteners and Other Sugar Substitutes: A Review of the Safety Issues". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 5 (2): 35–47. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.tb00081.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out52_en.pdf

- ^ Liang Y (1987). "The effect of artificial sweetener on insulin secretion. 1. The effect of acesulfame K on insulin secretion in the rat (studies in vivo)". Horm Metab Res. 19 (6): 233–238. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1011788. PMID 2887500.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Toxicity studies of acesulfame potassium" (PDF). National institutes of health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Public Health Service. "Toxicity Studies of Acesulfame Potassium" (PDF). Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Soffritti, Morando. "Acesulfame Potassium: Soffritti Responds". Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ Karstadt, Myra L. "Testing Needed for Acesulfame Potassium, an Artificial Sweetener". Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ^ "ffects of Mother's Dietary Exposure to Acesulfame-K in Pregnancy or Lactation on the Adult Offspring's Sweet Preference" (html). Chemical Senses, Volume: 36 Issue: 9 November 2011 p763-770. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

- ^ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat (2009). "Index, BP 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 4 February 2010.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives evaluation monograph of Acesulfame Potassium

- FDA approval of Acesulfame Potassium

- FDA approval of Acesulfame Potassium as a General Purpose Sweetener in Food

- International Food Information Council article (IFIC) Foundation Everything You Need to Know About Acesulfame Potassium

- Whole Foods Market Health Info Acesulfame K

- Elmhurst College, Illinois Virtual ChemBook Acesulfame K

- Hazardous substances databank entry at the national library of medicine (outdated source)

- Discovery News Sweeteners Linger in Groundwater