Royal Ulster Constabulary: Difference between revisions

| Line 236: | Line 236: | ||

Weapons: |

Weapons: |

||

*.38 Ruger Six Shot Revolver |

*.38 [[Ruger Speed Six]] 6 Shot Revolver |

||

*[[Ruger Mini-14]] |

*[[Ruger Mini-14]] |

||

Revision as of 16:31, 2 July 2012

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (August 2009) |

| Royal Ulster Constabulary | |

|---|---|

| {{{badgecaption}}} | |

| Abbreviation | RUC |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1 June 1922 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Dissolved | 2001 |

| Superseding agency | Police Service of Northern Ireland |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

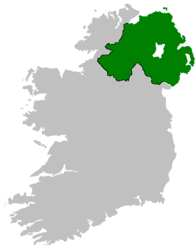

| National agency | Northern Ireland, UK |

| Operations jurisdiction | Northern Ireland, UK |

| |

| Map of Royal Ulster Constabulary's jurisdiction | |

| Size | 13,843 km² |

| General nature | |

The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was the name of the police force in Northern Ireland from 1922 to 2000. Following the awarding of the George Cross in 2000, it was subsequently known as the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC. It was founded on 1 June 1922 out of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).[1] At its peak the force had around 8,500 officers with a further 4,500 who were members of the RUC Reserve. During the Troubles, over 300 members of the RUC were killed and almost 9,000 injured in paramilitary assassinations or attacks, mostly by the Provisional IRA, which made the RUC (in 1983) the most dangerous police force in the world of which to be a member.[2][3]

It became the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) in 2001. The RUC was renamed and reformed, as is provided for by the final version of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 2000.[4] The RUC was continually accused by sections of the minority nationalist community and human rights groups of one-sided policing and discrimination, as well as for its collusion with loyalist paramilitaries (see below). Conversely, the RUC was praised by other security forces as one of the most professional policing operations in the world.[5] The allegations regarding collusion have prompted several inquiries, the most recent of which was published by Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan. No RUC Officer has been charged with any offence as a result of this report.

History

Early history

Under section 60 of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, Northern Ireland was placed under the jurisdiction of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). On 31 January 1921, Richard Dawson Bates, the first Minister of Home Affairs for Northern Ireland, appointed a committee of inquiry on police organisation in Northern Ireland. It was asked to advise on any alterations to the existing police necessary for the formation of a new force (i.e. recruitment and conditions of service, composition, strength and cost).

An interim report was published on 28 March 1922, the first official report of the new Parliament of Northern Ireland, and it was subsequently accepted by the Northern Ireland Government. On 29 April 1922, King George V granted to the force the name Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). In May, the Parliament of Northern Ireland passed the Constabulary Act 1922 and the RUC officially came into existence on 1 June. The headquarters of the force was established at Atlantic Buildings, Waring Street, in Belfast, and became the first Inspector General. The uniform remained essentially the same as that of the RIC - a dark green, as opposed to the dark blue worn by the other British police forces and the Garda Síochána. A new badge of the Red Hand of Ulster on a St George's cross surrounded by a chain was designed but proved unpopular and was never uniformly adopted. Eventually the Harp & Crown insignia of the Order of St Patrick as worn by the RIC was readopted.[6]

From the beginning it had a dual role, unique among British police forces, of providing a normal law enforcement police service while protecting Northern Ireland from the activities of proscribed groups. For personal protection its members were armed as the RIC had been.

The RUC was limited by statute to a 3,000-strong force. Initially, a third of positions within the force were reserved for Roman Catholics - a reflection of the proportions of the population of Northern Ireland at that time. The first two thousand places were filled quickly. Due to a slow recruitment rate from Catholics, the force resorted to normal recruitment in order to fill the remaining vacancies. As a result, representation of Catholics in the RUC never exceeded 20% and, by the 1960s, it had a Catholic representation of 12%.[7][8]

The RUC were supported by the Ulster Special Constabulary, a volunteer body of part-time auxiliary police established before the Northern Ireland Government was set up, who had been given uniforms and training. The RUC's senior officer, the Inspector General, was appointed by the Governor of Northern Ireland and was responsible to the Minister of Home Affairs in the Northern Ireland Government for the maintenance of law and order.

Neither the newly established Irish Free State nor Northern Ireland had an auspicious beginning. The polarised political climate in Northern Ireland resulted in violence from both sides of the political and religious divide. The lawlessness that affected Northern Ireland in the period of the early twenties, and the problems it caused for the police, are indicated in a police report drawn up by District Inspector R.R. Spears in February 1923. Referring to the situation in Belfast after July 1921 he states: "For twelve months after that, the city was in a state of turmoil. The IRA (Irish Republican Army) was responsible for an enormous number of murders, bombings, shootings and incendiary fires. The work of the police against them was, however, greatly hampered by the fact that the rough element on the Protestant side entered thoroughly into the disturbances, met murder with murder and adopted in many respects the tactics of the rebel gunmen. In the endeavour to cope simultaneously with the warring factions the police efforts were practically nullified. They were quite unable to rely on the restraint of one party while they dealt with the other". About 90 police officers were killed between 1920 and 1922 in what would become Northern Ireland. The security forces were also reportedly implicated in reprisal killings of Catholics, notably the McMahon Murders on 26 March 1922, in which six Catholics were killed and the Arnon Street Massacre on 1 April, where another six were shot dead in retaliation for the IRA killing of a policeman.[9][10]

By the mid-twenties the situation had calmed down. Northern Ireland enjoyed a peace, interrupted only occasionally, for the next forty-five years. The murder rate was lower than in the rest of the UK and the crime detection rate was higher.[11] The 1920s and 1930s were years of economic austerity. Many of Northern Ireland's traditional industries, notably linen and shipbuilding, were in recession. This contributed to the already high level of unemployment. Serious rioting broke out in 1932 in Belfast in protest at the inadequate nature of Poor Law relief and the threat of rioting was ever present. [citation needed]

In response to the growth of motorised transport the RUC Traffic Branch was formed on 1 January 1930. In 1936 the police depot at Enniskillen was formally opened and an £800,000 scheme to create a network of 196 police barracks throughout Northern Ireland by rationalizing or repairing the 224 premises inherited from the RIC was under way. In May 1937 a new white glass lamp with the RUC crest went up for the first time to replace the RIC crest still on many stations. About the same time the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) in Belfast was significantly expanded, with a detective head constable being appointed to head the CID force in each of the five Belfast police districts. [citation needed]

Sporadic IRA activity in the 1930s also required that the RUC be vigilant. In 1937, on the occasion of the visit of the King and Queen to the province, the IRA blew up a number of customs posts. In 1939. an IRA bombing campaign was launched in England. This campaign effectively ended on the 25 August, a few days before the outbreak of the Second World War. The war brought additional responsibilities for the police. The security of the land border with neutral Ireland was one important consideration. Allied to this was a greatly increased incidence of smuggling due to rationing, to the point where police virtually became revenue officers. There were also many wartime regulations to be enforced, including 'black-out' requirements on house and vehicle lights, the protection of post office and bank monies, and restrictions on the movement of vehicles and use of petrol. The RUC was a 'reserved occupation', i.e. the police force was deemed essential to the war effort on the Home Front and its members were forbidden to leave to join the other services. [citation needed]

The wartime situation gave a new urgency to the discussions regarding the appointment of women police. The Ministry of Home Affairs finally gave approval to the enrolment of women as members of the RUC on 16 April 1943. with the first six recruits starting on 15 November. Post-war policies brought about the gradual improvement in the lot of the RUC, interrupted only by a return to hostilities by the IRA. The IRA's border campaign of 1957-1962 killed seven RUC officers. The force was streamlined in the 1960s, a new headquarters was opened at Knock in Belfast and a number of rural barracks were closed. In 1967, the 42 hour work week was introduced.

The Troubles

The civil rights protests at the end of the 1960s, and the reaction to them, marked the beginning of the Troubles. The RUC continued its traditional pro-unionist role when it found itself confronting marchers protesting at the gerrymandering of local governmental electoral wards and the discrimination in local housing allocation. Many of these Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association protests were banned or truncated by the government of Northern Ireland. The B Specials, proved highly controversial to some, with the unit seen by some nationalists as more anti-Catholic and anti-nationalist than the RUC, which, unlike the B Specials, did attract some Catholic recruits. The severe pressure on the RUC and B-Specials led, during the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969, to the British Army being called in to support the civil administration under Operation Banner. Initially the army was welcomed by Catholic nationalists in preference to the RUC and in particular the B Specials (who were stood down on 30 April 1970). The Catholics mostly turned away from the Army over perceptions of unequal treatment and abuse, such as the events at Duke Street in Derry and Burntollet Bridge.

The high level of civil disturbance led to an exhaustive inquiry into the disturbances in Northern Ireland carried out by the distinguished English judge Lord Scarman, the then Home Secretary, James Callaghan, called on Lord Hunt to assess and advise on the policing situation. He was assisted in this task by Sir Robert Mark, who later became Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police Service, and Sir James Robertson, the then Chief Constable of Glasgow.

The report was published on 3 October 1969 and most of the recommendations subsequently accepted and implemented. The aim being a complete reorganisation of the RUC, with the aim of both modernizing the force and bringing it into line with the other police forces in the UK. This meant the introduction of the British rank and promotion structure, the creation of 12 Police Divisions and 39 Sub-Divisions, the disbandment of the Ulster Special Constabulary,[12] and the creation of a Police Authority representative of the whole community.

Callaghan asked Sir Arthur Young, Commissioner of the City of London Police, to be seconded for a year. Young's appointment began the long process of turning the RUC into a British police service. The RUC Reserve was formed as an auxiliary police force, and all military-style duties were handed over to the newly formed Ulster Defence Regiment, which was under military command and replaced the B Specials.[citation needed]

Callaghan picked Young, a career policeman, because no other British policeman could match his direct experience of policing acutely unstable societies and of reforming gendarmeries. From 1943 to 1945, he was Director of Public Safety and Director of Security in the military government of Allied-occupied Italy. Later, he had been seconded to the Federation of Malaya at the height of the Malayan Emergency (1952–53) and to the crown colony of Kenya during Mau Mau (1954).[13]

The first deaths of the Troubles occurred in July 1969. Francis McCloskey, a 67-year old Catholic civilian had been found unconscious on 13 July near the Dungiven Orange Hall following a police baton charge against a crowd who had been throwing stones at the hall. Witnesses later said they had seen police batoning a figure in the doorway where McCloskey was found, although police claimed that he had been unconscious before the baton charge and may have been hit with a stone. He was taken to hospital and died the following day.[14][15] On 11 October 1969, Constable Victor Arbuckle was shot dead by loyalists on Belfast's Shankill Road during serious rioting in protest at the recommendations of the Hunt Report. He became the first police fatality of the Troubles. In August 1970, two young constables, Donaldson and Millar, died when an abandoned car they were examining near Crossmaglen exploded. They became the first victims of the re-organized Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) campaign. This campaign involved the targeting of police officers, and continued until the final ceasefire in 1997, as the peace process gained momentum. (The last police officer to be murdered was Constable O'Reilly (a Catholic), who was killed by a Loyalist bomb in September 1998 during the Drumcree conflict.)

In March 1972, the Government of Northern Ireland resigned and the parliament was prorogued. Northern Ireland subsequently came under direct rule from Westminster with its own Secretary of State, who had overall responsibility for security policy. Starting in late 1982, a number of IRA and Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) men were shot dead by the RUC. This led to accusations of a shoot-to-kill policy by the RUC. In September 1983, four officers were charged with murder in connection with the deaths. Although all were subsequently found not guilty, the British government set up the Stalker Inquiry to further investigate.

In May 1986 John Hermon, then Chief Constable, publicly accused Unionist politicians of "consorting with paramilitary elements". Anger at the Anglo-Irish Agreement led to unionists attacking over five hundred homes, of Catholics and RUC officers in the mid-1980s. At least 150 RUC families were forced to move as a result.[citation needed]

In 1998 Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan stated in an interview on television that he was unhappy with any RUC officers belonging to the Orange Order or any of the other loyal orders. [citation needed] While the RUC refused to give any details on how many officers were members of the Order, thirty-nine RUC officers are listed on the Order's Roll of Honour (of Orangemen killed in the conflict). [citation needed]

The size of the RUC increased on several occasions. At its height, there were 8,500 regular police officers supported by about 5,000 full-time and part-time reserve officers, making it the second largest force in the United Kingdom after the Metropolitan Police in London. The direction and control of the RUC was in the hands in the Chief Constable, who was assisted by two Deputy Chief Constables and nine Assistant Chief Constables. For operational purposes, Northern Ireland was divided into twelve Divisions and thirty-nine Sub-Divisions. RUC ranks, duties, conditions of service and pay were generally in line with those of police forces in Great Britain.[citation needed]

Policing in a divided society

Policing Northern Ireland's divided society proved difficult, as each community (nationalist and unionist) had different attitudes towards the institutions of the state.[16] To unionists, the state had full legitimacy, as did its institutions, its parliament, the Crown and its police force. Northern Ireland's Catholics, overwhelmingly nationalists, had been told by their leaders that Partition was temporary.[17] They and their politicians had therefore refused to take part in the Province's institutions in the mistaken belief that Northern Ireland would be ceded to the South.[18] Unionist fears of fundamental government services being infiltrated by Catholics disloyal to the new state polarised society and made many Catholics unwilling or unable to join the police or civil service.[19]

This mindset was expressed by David Trimble in the following terms: "Ulster Unionists, fearful of being isolated on the island, built a solid house, but it was a cold house for Catholics. And northern nationalists, although they had a roof over their heads, seemed to us as if they meant to burn the house down".[20]

From a nationalist perspective, the tone was set for the force at an early stage, when Dawson Bates in August 1922 gave the Orange Order special permission for an Orange Lodge to be formed in the RUC. In April 1923 he would speak at its first reunion, later however involvement in politics was "discouraged". In 1924 John Nixon a District Inspector would be dismissed after widespread complaints after making a "fiercely Unionist" speech at an Orange Order function. Despite this the force's character had been fixed according to Irish nationalist activist and author Michael Farrell. According to Farrell they were looked upon by most Catholics as simply the “coercive arm of the Unionist Party”. [citation needed] The minister with responsibility was an Orangeman, with a police Orange Lodge; therefore he contends the RUC could scarcely be unbiased where the Unionist Party or the Orange Order was concerned. An enquiry by the British National Council for Civil Liberties in 1936 stated: "[i]t is difficult to escape the conclusion that the attitude of the government renders the police chary of interference with the activities of the Orange Order and its sympathisers".[21]

On 4 April 1922 the RIC was disbanded. On 7 April the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act (Northern Ireland) 1922 came into force, and the Belfast government though prohibited from raising or controlling a military force appointed Major General Solly Flood as a military advisor.[22]

The RUC was to be 3,000-strong, recruiting 2,000 ex-RIC and 1,000 A Specials. Half of the RIC men recruited were to be Catholic, making up a third of positions within the force. Fewer than half the required number of Catholics came forward and the balance was made up with more A Specials, who continued to exist as a separate force.[22]

Throughout its existence, republican political leaders and Roman Catholic clergy urged members of the nationalist community not to join the RUC. Social Democratic and Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP) and critic of the force Seamus Mallon, who later served as Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland, stated that the RUC was "97% Protestant and 100% unionist".

The RUC did attract some Roman Catholic members. These men were for the most part former members of the RIC, who came north from the Irish Republic after the Irish Free State was set up. The bitterness of the fighting in the Anglo-Irish War precluded them from remaining in territory now controlled by their former enemies. The percentage of Catholics in the RUC dropped as these men retired over time.[citation needed] IRA attacks on Catholics who joined the RUC, and the perception that the police force was "a Protestant force for a Protestant people" meant that Catholic participation in the Royal Ulster Constabulary always remained disproportionally small in terms of the Catholic percentage of the overall Northern Irish population. Notable exceptions include RUC Chief Constable Sir James Flanagan KBE (Derry), Deputy Chief Constable Michael McAtamney, Assistant Chief Constable Cathal Ramsey, Chief Superintendent Frank Lagan[23] as well as RUC Superintendents Kevin Benedict Sheehy (Glengormley) and Brendan McGuigan.

In December 1997, London's The Independent newspaper published a leaked internal RUC document which reported that a third of all Catholic RUC officers had suffered religious discrimination and/or harassment from Protestant fellow officers.[24]

Casualties

According to official sources, 314 officers were killed and over 9000 were injured during the history of the RUC. All but 12 of the dead were killed in the Troubles (1969 to 1998), of whom 277 were killed in attacks by Irish republican groupings.[25] However, according to the CAIN project at the University of Ulster,[26] 301 active RUC officers were killed and 18 ex-RUC officers, which would total 319 fatalities during the Troubles.

Twenty former RUC officers were killed by acts of terrorism after leaving the service while two members of the Police Authority and three of its employees were killed between 1972 and 1994.[27]

The Newry mortar attack by the Provisional IRA on an RUC station in 1985, which killed nine officers, resulted in the highest number of deaths inflicted on the RUC in one incident.

The two highest-ranking RUC officers to be killed in the Troubles were Chief Superintendent Harry Breen and Superintendent Robert Buchanan when they were ambushed by the Provisional IRA South Armagh Brigade outside Jonesborough, County Armagh, on 20 March 1989.

The last RUC officer to be killed as a direct result of the conflict died on the 6 October 1998, a month after he had been injured in a Red Hand Defenders pipe-bomb attack in Portadown.[28]

Criticism

Ill-treatment of children

On 1 July 1992, Human Rights Watch (HRW) issued a detailed report on RUC and paramilitary violations against children's rights during The Troubles. Both Catholic and Protestant children alleged regular and severe physical assault and mental harassment at the hands of RUC officers, usually conducted to force a false confession of a crime.[29] In an accompanying statement, HRW said:

Police officers and soldiers harass young people on the street hitting, kicking and insulting them. Police officers in interrogation centres insult, trick and threaten youngsters and sometimes physically assault them. Children are locked up in adult detention centres and prisons in shameful conditions. The extent of the violence inflicted on children is appalling. Helsinki Watch heard dozens of stories from children, their parents, lawyers, youth workers and political leaders of children being stopped on the street and hit, kicked and abused again and again by police and soldiers. And seventeen-year-olds told Helsinki Watch of severe beatings in detention during interrogations by police.[30]

No response has been issued by the British Government or by Northern Ireland paramilitaries, despite requests from various European bodies and human rights organisations.[29]

Patten report

The Good Friday Agreement (1998), produced a wholesale reorganisation of inter-community, governmental and policing systems, including a power-sharing executive with David Trimble and the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party's (SDLP) Seamus Mallon (later replaced by new party leader Mark Durkan) as co-chairmen. The perceived bias, and the clear under-representation of Catholics and nationalists in the RUC [citation needed] led to, as part of the Good Friday Agreement, a fundamental policing review, headed by Chris Patten, a former Hong Kong Governor and British Conservative Minister under Margaret Thatcher. The review was published in September 1999. It recommended a wholesale reorganisation of policing, with the Royal Ulster Constabulary being renamed the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), and a greater drive to recruit Catholic recruits and should adopt a new crest and cap badge. [citation needed]

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) was introduced in November 2001. As part of the change, the police service dropped the word "Royal" from everyday usage and adopted a new badge that included the crown, harp, and shamrock, an attempt at shared identification with both communities. [citation needed]

Loyalist collusion

Special Patrol Group

Elements of the RUC are alleged to have colluded extensively with loyalist paramilitaries throughout the 30-year conflict in Northern Ireland. Particularly prominent in this regard were the actions of the specialist anti-terrorist unit, the Special Patrol Group. This unit was formed in the early 1970s and was disbanded in 1980 after two of its members were convicted of terrorist offences including kidnap and murder. The two, John Weir and Billy McCaughey implicated their colleagues in a range of crimes including giving weapons, information and transport to loyalist paramilitaries as well as carrying out shooting and bombing attacks of their own.[31]

The Stevens Inquiry

On 18 April 2003 as part of the third report into collusion between Loyalist paramilitaries, RUC, and British Army, Sir John Stevens published an Overview and Recommendations document (Stevens 3).[32] Stevens intention was to make recommendations which arose from serious shortcomings he had identified in all three Enquiries.[33] In his autobiography, Stevens was at pains to point out the outstanding loyalty and shared dedication to justice that he experienced from many RUC officers. He mentions many names including Detective Superintendent Maurice Neely, who died in the 1994 Chinook air crash.[34]

The third Stevens Inquiry began in 1999, and referred to his previous reports when making his recommendations. Stevens third inquiry focused in detail on only two of the murders in which collusion is alleged; the murder of Brian Adam Lambert in 1987 & the killing of Pat Finucane in 1989.

Stevens used the following criteria as a definition of collusion while conducting his investigation:

- The failure to keep records or the existence of contradictory accounts which could limit the opportunity to rebut serious allegations.

- The absence of accountability which could allow acts or omissions by individuals to go undetected.

- The withholding of information which could impede the prevention of crime and the arrest of suspects.

- The unlawful involvement of agents in murder which could imply that the security forces sanction killings.[35]

Noted in the report was that as a result of the Stevens 3 inquiries and up to the date of publication there had been 144 arrests with 94 people convicted, along with fifty-seven separate reports submitted to the Northern Ireland Director of Public Prosecutions.

Despite an investigation that stretched almost 20 years no RUC Officer (or latterly, no PSNI Officer) has ever been charged with any offence.

Police Ombudsman

In a report released on the 22 January 2007, the Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan stated Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) informers committed serious crimes, including murder, with the full knowledge of their handlers.[36] The report stated Special Branch officers created false statements, blocked evidence searches and "baby-sat" suspects during interviews. Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) councillor and former Police Federation chairman Jimmy Spratt said if the report "had had one shred of credible evidence then we could have expected charges against former Police Officers. There are no charges, so the public should draw their own conclusion, the report is clearly based on little fact".[37] However, Northern Ireland Secretary of State Peter Hain said that he was "convinced that at least one prosecution will arise out of today's report".[38]

Awards

Awards for gallantry for individual officers since 1969 included 16 George Medals, 103 Queen's Gallantry Medals, 111 Queen's Commendations for Bravery and 69 Queen's Police Medals.[39]

On 12 April 2000, the RUC was awarded the George Cross for bravery in dealing with terrorist threat,[40] a rare honour which had only been awarded collectively once before, to the island nation of Malta. The Award stated "For the past 30 years, the Royal Ulster Constabulary has been the bulwark against, and the main target of, a sustained and brutal terrorism campaign. The Force has suffered heavily in protecting both sides of the community from danger - 302 officers have been killed in the line of duty and thousands more injured, many seriously. Many officers have been ostracised by their own community and others have been forced to leave their homes in the face of threats to them and their families. As Northern Ireland reaches a turning point in its political development this award is made to recognise the collective courage and dedication to duty of all of those who have served in the Royal Ulster Constabulary and who have accepted the danger and stress this has brought to them and to their families."

Chief officers

The chief officer of the Royal Irish Constabulary was its Inspector-General (the last of whom, Sir Thomas J. Smith served from 11 March 1920 until partition in 1922). Between 1922 and 1969 the position of Inspector-General of the RUC was held by five officers, the last being Sir Arthur Young, who was seconded for a year from the City of London Police to implement the Hunt Report and disarm the police and disband the Ulster Special Constabulary ('B' Specials). Under Young the title was changed to Chief Constable in line with the recommendations of the Hunt Report. Young and six others held the job until the RUC was incorporated to the new Police Service. The final incumbent, Sir Ronnie Flanagan, became the first Chief Constable of the PSNI.

- Inspector-General Sir Charles George Wickham, from June 1922.

- Inspector-General Sir Richard Pim, from August 1945.

- Inspector-General Sir Albert Kennedy, from January 1961.

- Inspector-General J.A. Peacock, from February 1969.

- Inspector-General Sir Arthur Young, from November 1969.

- Chief Constable Sir Graham Shillington, from November 1970.

- Chief Constable Sir James Flanagan, from November 1973.

- Chief Constable Sir Kenneth Newman, from May 1976.

- Chief Constable Sir John Hermon, from January 1980.

- Chief Constable Sir Hugh Annesley, from June 1989.

- Chief Constable Sir Ronnie Flanagan, from October 1996 - November 2001, continuing as Chief Constable of the PSNI until April 2002

Ranks

1922 to 1930

- Inspector-General (insignia of a Brigadier)

- Deputy Inspector-General (insignia of a Colonel)

- County Inspector (insignia of a Lieutenant-Colonel)

- District Inspector 1st Class (insignia of a Major)

- District Inspector 2nd Class (insignia of a Captain)

- District Inspector 3rd Class (insignia of a Lieutenant)

- Head Constable Major (insignia of a Sergeant-Major)

- Head Constable (equivalent to Staff Sergeant)

- Sergeant (insignia of a Sergeant)

- Constable (serial number)

1930 to 1970

- Inspector-General (insignia of a Lieutenant-General)

- Deputy Inspector-General (insignia of a Major-General)

- Commissioner (insignia of a Brigadier)

- County Inspector (insignia of a Colonel)

- District Inspector 1st Class (insignia of a Lieutenant-Colonel)

- District Inspector 2nd Class (insignia of a Major)

- District Inspector 3rd Class (insignia of a Captain)

- Head Constable Major (insignia of a Sergeant-Major)

- Head Constable (equivalent to Staff Sergeant)

- Sergeant (insignia of a Sergeant)

- Constable (serial number)

In 1970, the military-style rankings and insignia were dropped in favour of the standard UK police ranks.

1970 to 2001

- Chief Constable

- Deputy Chief Constable

- Assistant Chief Constable

- Chief Superintendent

- Superintendent

- Chief Inspector

- Inspector

- Sergeant

- Constable

- Reserve Constable[41]

Equipment

Vehicles:

Weapons:

- .38 Ruger Speed Six 6 Shot Revolver

- Ruger Mini-14

References

- ^ The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415-058-5 p5

- ^ bjc.oxfordjournals.org

- ^ CNN

- ^ opsi.gov.uk

- ^

"The RUC: Lauded and condemned". BBC News. bbc.co.uk. 31 October 2001. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

Condemned by republicans, nationalists and human rights groups for embodying sectarianism and lauded by security forces as one of the most professional police operations in the world, the Royal Ulster Constabulary is one of the most controversial police forces in the UK.

- ^ The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415-058-5 p17

- ^ Morrison, John. "The Ulster Government and Internal Opposition". The Ulster Cover-Up. Lurgan, County Armagh: Ulster Society (Publications) Ltd. pp. 39–40. ISBN 1-872076-15-7.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Conflict and Hope in Northern Ireland". Cable News Network (CNN). 2000. Retrieved 9 November 2008. [dead link]

- ^ Robert Lynch the Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition, p122-123

- ^ Alan F Parkison, Belfast's Unholy War, p245-248

- ^ Morrison, John. "The Ulster Government's External Relations". The Ulster Cover-Up. Lurgan, County Armagh: Ulster Society (Publications) Ltd. p. 26. ISBN 1-872076-15-7.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ BBC

- ^ Sir Arthur Young biodata

- ^ David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brian Feeney and Chris Thornton, Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland Troubles, Edinburgh, 1999, p.32.

- ^ CAIN-1969

- ^ Weitzer 1985, 1995

- ^ The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415-058-5, p. 27

- ^ The Thin Green Line, op cit, p. 27

- ^ The Thin Green Line, op cit]

- ^ David Trimble - Nobel Lecture

- ^ Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Pluto Press (1992 RP), ISBN 0-86104-300-6, pp. 96, 97

- ^ a b Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State, Pluto Press (1992 RP), ISBN 0-86104-300-6, p. 54

- ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards' official website

- ^ Discrimination survey

- ^ The Thin Green Line, op cit, p. 271

- ^ CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths

- ^ policememorial.org.uk

- ^ cain.ulst.ac.uk

- ^ a b Children in Northern Ireland: Abused by Security Forces and Paramilitaries, Human Rights Watch Helsinki Cite error: The named reference "Cearta2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Children in Northern Ireland, Human Rights Watch

- ^ Center for Civil & Human Rights

- ^ Overview and Recommendations document for Stevens 3 is available in PDF format here.

- ^ For a chronology of the Stevens Inquiries and surrounding events see BBC News 17 April 2003 available here.

- ^ p165 John Stevens Not for the Faint-Hearted; Weidenfield & Nicholson; 2005 ISBN 978-0-297-84842-4

- ^ Conclusions section of Stevens 3 Overview and Recommendations document, p. 16

- ^ Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland on her investigations into the circumstances surrounding the death of Raymond McCord Junior and related matters

- ^ BBC News, Monday, 22 January 2007. Reaction to Ombudsman's report

- ^ BBC News, Monday, 22 January 2007. NI police colluded with killers

- ^ RUC awards

- ^ Queen honours NI police, BBC

- ^ uniforminsignia.net

Further reading

- Weitzer, Ronald, 1985. "Policing a Divided Society: Obstacles to Normalization in Northern Ireland," Social Problems, v. 33 (October), pp. 41–55.

- Weitzer, Ronald, 1995. Policing Under Fire: Ethnic Conflict and Police-Community Relations in Northern Ireland (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press).

- Chris Ryder (1989, 1992, 1997), The RUC: A force under fire. London: Mandarin. ISBN 978-0-7493-2379-0.

- Graham Ellison, Jim Smyth (2000), The Crowned Harp: Policing Northern Ireland. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1393-1.

External links

- Police Service of Northern Ireland

- Policing - Details of Source Material, CAIN, University of Ulster

- RUC GC Foundation

- Royal Ulster Constabulary GC Memorial Website

- RUC Roll of Honour

- Use dmy dates from September 2010

- 2001 disestablishments

- Collective recipients of the George Cross

- Defunct law enforcement agencies of Ireland

- Defunct police forces of the United Kingdom

- Defunct gendarmeries

- History of Northern Ireland

- Royal Ulster Constabulary

- Police forces of Northern Ireland

- Organizations established in 1922

- 1922 establishments in Northern Ireland