History of the camera: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

m Reverted edits by 76.26.162.61 (talk) to last revision by Jim1138 (HG) |

|||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

[[File:Canon RC-701 img 0829.jpg|thumb|Canon RC-701, 1986]] |

[[File:Canon RC-701 img 0829.jpg|thumb|Canon RC-701, 1986]] |

||

Analog electronic cameras do not appear to have reached the market until 1986 with the Canon RC-701. Canon demonstrated a prototype of this model at the [[1984 Summer Olympics]], printing the images in the ''[[Yomiuri |

Analog electronic cameras do not appear to have reached the market until 1986 with the Canon RC-701. Canon demonstrated a prototype of this model at the [[1984 Summer Olympics]], printing the images in the ''[[Yomiuri Shinbun]]'', a Japanese newspaper. In the United States, the first publication to use these cameras for real reportage was [[USA Today]], in its coverage of World Series baseball. Several factors held back the widespread adoption of analog cameras; the cost (upwards of [[United States Dollar|$]]20,000), poor image quality compared to film, and the lack of quality affordable printers. Capturing and printing an image originally required access to equipment such as a frame grabber, which was beyond the reach of the average consumer. The "video floppy" disks later had several reader devices available for viewing on a screen, but were never standardized as a computer drive. |

||

The early adopters tended to be in the news media, where the cost was negated by the utility and the ability to transmit images by telephone lines. The poor image quality was offset by the low resolution of newspaper graphics. This capability to transmit images without a satellite link was useful during the [[Tiananmen Square protests of 1989]] and the first [[Gulf War]] in 1991. |

The early adopters tended to be in the news media, where the cost was negated by the utility and the ability to transmit images by telephone lines. The poor image quality was offset by the low resolution of newspaper graphics. This capability to transmit images without a satellite link was useful during the [[Tiananmen Square protests of 1989]] and the first [[Gulf War]] in 1991. |

||

Revision as of 08:08, 3 December 2012

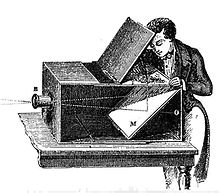

The history of the camera can be traced much further back than the introduction of photography. Photographic cameras evolved from the camera obscura, and continued to change through many generations of photographic technology, including daguerreotypes, calotypes, dry plates, film, and digital cameras.

The camera obscura

Photographic cameras were a development of the camera obscura, a device dating back to the ancient Chinese[1] and ancient Greeks,[2][3] which uses a pinhole or lens to project an image of the scene outside upside-down onto a viewing surface.

Scientist-monk Roger Bacon also studied the matter. Bacon's notes and drawings, published as Perspectiva in 1267, are partly clouded with theological material describing how the Devil can insinuate himself through the pinhole by magic,[4] and it is not clear whether or not he produced such a device. On 24 January 1544 mathematician and instrument maker Reiners Gemma Frisius of Leuven University used one to watch a solar eclipse, publishing a diagram of his method in De Radio Astronimica et Geometrico in the following year.[5] In 1558 Giovanni Batista della Porta was the first to recommend the method as an aid to drawing.[6]

Before the invention of photographic processes there was no way to preserve the images produced by these cameras apart from manually tracing them. The earliest cameras were room-sized, with space for one or more people inside; these gradually evolved into more and more compact models such as that by Niépce's time portable handheld cameras suitable for photography were readily available. The first camera that was small and portable enough to be practical for photography was built by Johann Zahn in 1685, though it would be almost 150 years before such an application was possible.

Early fixed images

The first partially successful photograph of a camera image was made in approximately 1816 by Nicéphore Niépce[7][8] using a very small camera of his own making and a piece of paper coated with silver chloride, which darkened where it was exposed to light. No means of removing the remaining unaffected silver chloride was known to Niépce, so the photograph was not permanent, eventually becoming entirely darkened by the overall exposure to light necessary for viewing it. Later, in 1826, he used a sliding wooden box camera made by Charles and Vincent Chevalier in Paris, France. He made his first permanent camera photograph in 1826 by coating a pewter plate with bitumen and exposing the plate in this camera.[9] The bitumen hardened where light struck. The unhardened areas were then dissolved away. This photograph still survives.

Daguerreotypes and calotypes

Louis Daguerre and Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (who was Daguerre's partner, but died before their invention was completed) invented the first practical photographic method, which was named the daguerreotype, in 1836. Daguerre coated a copper plate with silver, then treated it with iodine vapor to make it sensitive to light. The image was developed by mercury vapor and fixed with a strong solution of ordinary salt (sodium chloride). Henry Fox Talbot perfected a different process, the calotype, in 1840. Both used cameras that were little different from Zahn's model, with a sensitized plate or sheet of paper placed in front of the viewing screen to record the image. Focusing was generally via sliding boxes.[10]

Dry plates

Collodion dry plates had been available since 1855, thanks to the work of Désiré van Monckhoven, but it was not until the invention of the gelatin dry plate in 1871 by Richard Leach Maddox that they rivaled wet plates in speed and quality. Also, for the first time, cameras could be made small enough to be hand-held, or even concealed. There was a proliferation of various designs, from single- and twin-lens reflexes to large and bulky field cameras, handheld cameras, and even "detective cameras" disguised as pocket watches, hats, or other objects.

The shortened exposure times that made candid photography possible also necessitated another innovation, the mechanical shutter. The very first shutters were separate accessories, though built-in shutters were common by around the start of the 20th century.[10]

Kodak and the birth of film

The use of photographic film was pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing paper film in 1885 before switching to celluloid in 1889. His first camera, which he called the "Kodak," was first offered for sale in 1888. It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer. The Kodak came pre-loaded with enough film for 100 exposures and needed to be sent back to the factory for processing and reloading when the roll was finished. By the end of the 19th century Eastman had expanded his lineup to several models including both box and folding cameras.

In 1900, Eastman took mass-market photography one step further with the Brownie, a simple and very inexpensive box camera that introduced the concept of the snapshot. The Brownie was extremely popular and various models remained on sale until the 1960s.

Film also allowed the movie camera to develop from an expensive toy to a practical commercial tool.

Despite the advances in low-cost photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered higher-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century. To compete with rollfilm cameras, which offered a larger number of exposures per loading, many inexpensive plate cameras from this era were equipped with magazines to hold several plates at once. Special backs for plate cameras allowing them to use film packs or rollfilm were also available, as were backs that enabled rollfilm cameras to use plates.

Except for a few special types such as Schmidt cameras, most professional astrographs continued to use plates until the end of the 20th century when electronic photography replaced them.

35 mm

Oskar Barnack, who was in charge of research and development at Leitz, decided to investigate using 35 mm cine film for still cameras while attempting to build a compact camera capable of making high-quality enlargements. He built his prototype 35 mm camera (Ur-Leica) around 1913, though further development was delayed for several years by World War I. Leitz test-marketed the design between 1923 and 1924, receiving enough positive feedback that the camera was put into production as the Leica I (for Leitz camera) in 1925. The Leica's immediate popularity spawned a number of competitors, most notably the Contax (introduced in 1932), and cemented the position of 35 mm as the format of choice for high-end compact cameras.

Kodak got into the market with the Retina I in 1934, which introduced the 135 cartridge used in all modern 35 mm cameras. Although the Retina was comparatively inexpensive, 35 mm cameras were still out of reach for most people and rollfilm remained the format of choice for mass-market cameras. This changed in 1936 with the introduction of the inexpensive Argus A and to an even greater extent in 1939 with the arrival of the immensely popular Argus C3. Although the cheapest cameras still used rollfilm, 35 mm film had come to dominate the market by the time the C3 was discontinued in 1966.

The fledgling Japanese camera industry began to take off in 1936 with the Canon 35 mm rangefinder, an improved version of the 1933 Kwanon prototype. Japanese cameras would begin to become popular in the West after Korean War veterans and soldiers stationed in Japan brought them back to the United States and elsewhere.

TLRs and SLRs

The first practical reflex camera was the Franke & Heidecke Rolleiflex medium format TLR of 1928. Though both single- and twin-lens reflex cameras had been available for decades, they were too bulky to achieve much popularity. The Rolleiflex, however, was sufficiently compact to achieve widespread popularity and the medium-format TLR design became popular for both high- and low-end cameras.

A similar revolution in SLR design began in 1933 with the introduction of the Ihagee Exakta, a compact SLR which used 127 rollfilm. This was followed three years later by the first Western SLR to use 35mm film, the Kine Exakta (World's first true 35mm SLR was Soviet "Sport" camera, marketed several months before Kine Exakta, though "Sport" used its own film cartridge). The 35mm SLR design gained immediate popularity and there was an explosion of new models and innovative features after World War II. There were also a few 35mm TLRs, the best-known of which was the Contaflex of 1935, but for the most part these met with little success.

The first major post-war SLR innovation was the eye-level viewfinder, which first appeared on the Hungarian Duflex in 1947 and was refined in 1948 with the Contax S, the first camera to use a pentaprism. Prior to this, all SLRs were equipped with waist-level focusing screens. The Duflex was also the first SLR with an instant-return mirror, which prevented the viewfinder from being blacked out after each exposure. This same time period also saw the introduction of the Hasselblad 1600F, which set the standard for medium format SLRs for decades.

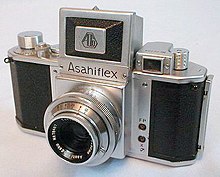

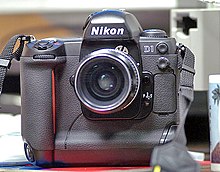

In 1952 the Asahi Optical Company (which later became well known for its Pentax cameras) introduced the first Japanese SLR using 35mm film, the Asahiflex. Several other Japanese camera makers also entered the SLR market in the 1950s, including Canon, Yashica, and Nikon. Nikon's entry, the Nikon F, had a full line of interchangeable components and accessories and is generally regarded as the first system camera. It was the F, along with the earlier S series of rangefinder cameras, that helped establish Nikon's reputation as a maker of professional-quality equipment.

Instant cameras

While conventional cameras were becoming more refined and sophisticated, an entirely new type of camera appeared on the market in 1948. This was the Polaroid Model 95, the world's first viable instant-picture camera. Known as a Land Camera after its inventor, Edwin Land, the Model 95 used a patented chemical process to produce finished positive prints from the exposed negatives in under a minute. The Land Camera caught on despite its relatively high price and the Polaroid lineup had expanded to dozens of models by the 1960s. The first Polaroid camera aimed at the popular market, the Model 20 Swinger of 1965, was a huge success and remains one of the top-selling cameras of all time.

Automation

The first camera to feature automatic exposure was the selenium light meter-equipped, fully automatic Super Kodak Six-20 of 1938, but its extremely high price (for the time) of $225 (4870 in present terms[11]) kept it from achieving any degree of success. By the 1960s, however, low-cost electronic components were commonplace and cameras equipped with light meters and automatic exposure systems became increasingly widespread.

The next technological advance came in 1960, when the German Mec 16 SB subminiature became the first camera to place the light meter behind the lens for more accurate metering. However, through-the-lens metering ultimately became a feature more commonly found on SLRs than other types of camera; the first SLR equipped with a TTL system was the Topcon RE Super of 1962.

Digital cameras

Digital cameras differ from their analog predecessors primarily in that they do not use film, but capture and save photographs on digital memory cards or internal storage instead. Their low operating costs have relegated chemical cameras to niche markets. Digital cameras now include wireless communication capabilities (for example Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) to transfer, print or share photos, and are commonly found on mobile phones.

Early development

The concept of digitizing images on scanners, and the concept of digitizing video signals, predate the concept of making still pictures by digitizing signals from an array of discrete sensor elements. At Philips Labs. In New York, Edward Stupp, Pieter Cath and Zsolt Szilagyi filed for a patent on "All Solid State Radiation Imagers" on 6 September 1968 and constructed a flat-screen target for receiving and storing an optical image on a matrix composed of an array of photodiodes connected to a capacitor to form an array of two terminal devices connected in rows and columns. Their US patent was granted on 10 November 1970.[12] Texas Instruments engineer Willis Adcock designed a filmless camera that was not digital and applied for a patent in 1972, but it is not known whether it was ever built.[13] The first recorded attempt at building a digital camera was in 1975 by Steven Sasson, an engineer at Eastman Kodak.[14][15] It used the then-new solid-state CCD image sensor chips developed by Fairchild Semiconductor in 1973.[16] The camera weighed 8 pounds (3.6 kg), recorded black and white images to a compact cassette tape, had a resolution of 0.01 megapixels (10,000 pixels), and took 23 seconds to capture its first image in December 1975. The prototype camera was a technical exercise, not intended for production.

Analog electronic cameras

Handheld electronic cameras, in the sense of a device meant to be carried and used like a handheld film camera, appeared in 1981 with the demonstration of the Sony Mavica (Magnetic Video Camera). This is not to be confused with the later cameras by Sony that also bore the Mavica name. This was an analog camera, in that it recorded pixel signals continuously, as videotape machines did, without converting them to discrete levels; it recorded television-like signals to a 2 × 2 inch "video floppy".[17] In essence it was a video movie camera that recorded single frames, 50 per disk in field mode and 25 per disk in frame mode. The image quality was considered equal to that of then-current televisions.

Analog electronic cameras do not appear to have reached the market until 1986 with the Canon RC-701. Canon demonstrated a prototype of this model at the 1984 Summer Olympics, printing the images in the Yomiuri Shinbun, a Japanese newspaper. In the United States, the first publication to use these cameras for real reportage was USA Today, in its coverage of World Series baseball. Several factors held back the widespread adoption of analog cameras; the cost (upwards of $20,000), poor image quality compared to film, and the lack of quality affordable printers. Capturing and printing an image originally required access to equipment such as a frame grabber, which was beyond the reach of the average consumer. The "video floppy" disks later had several reader devices available for viewing on a screen, but were never standardized as a computer drive.

The early adopters tended to be in the news media, where the cost was negated by the utility and the ability to transmit images by telephone lines. The poor image quality was offset by the low resolution of newspaper graphics. This capability to transmit images without a satellite link was useful during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and the first Gulf War in 1991.

US government agencies also took a strong interest in the still video concept, notably the US Navy for use as a real time air-to-sea surveillance system.

The first analog electronic camera marketed to consumers may have been the Canon RC-250 Xapshot in 1988. A notable analog camera produced the same year was the Nikon QV-1000C, designed as a press camera and not offered for sale to general users, which sold only a few hundred units. It recorded images in greyscale, and the quality in newspaper print was equal to film cameras. In appearance it closely resembled a modern digital single-lens reflex camera. Images were stored on video floppy disks.

Silicon Film, a proposed digital sensor cartridge for film cameras that would allow 35 mm cameras to take digital photographs without modification was announced in late 1998. Silicon Film was to work like a roll of 35 mm film, with a 1.3 megapixel sensor behind the lens and a battery and storage unit fitting in the film holder in the camera. The product, which was never released, became increasingly obsolete due to improvements in digital camera technology and affordability. Silicon Films' parent company filed for bankruptcy in 2001.[18]

The arrival of true digital cameras

The first true digital camera that recorded images as a computerized file was likely the Fuji DS-1P of 1988, which recorded to a 16 MB internal memory card that used a battery to keep the data in memory. This camera was never marketed in the United States, and has not been confirmed to have shipped even in Japan.

The first commercially available digital camera was the 1990 Dycam Model 1; it also sold as the Logitech Fotoman. It used a CCD image sensor, stored pictures digitally, and connected directly to a computer for download.[19][20][21]

In 1991, Kodak brought to market the Kodak DCS-100, the beginning of a long line of professional Kodak DCS SLR cameras that were based in part on film bodies, often Nikons. It used a 1.3 megapixel sensor and was priced at $13,000.

The move to digital formats was helped by the formation of the first JPEG and MPEG standards in 1988, which allowed image and video files to be compressed for storage. The first consumer camera with a liquid crystal display on the back was the Casio QV-10 developed by a team lead by Hiroyuki Suetaka in 1995 after the first digital camera released on the consumer market by his team 8 years earlier had flopped.[citation needed] The first camera to use CompactFlash was the Kodak DC-25 in 1996.[citation needed]

The marketplace for consumer digital cameras was originally low resolution (either analog or digital) cameras built for utility. In 1997 the first megapixel cameras for consumers were marketed. The first camera that offered the ability to record video clips may have been the Ricoh RDC-1 in 1995.

1999 saw the introduction of the Nikon D1, a 2.74 megapixel camera that was the first digital SLR developed entirely by a major manufacturer, and at a cost of under $6,000 at introduction was affordable by professional photographers and high-end consumers. This camera also used Nikon F-mount lenses, which meant film photographers could use many of the same lenses they already owned.

See also

References

- ^ Needham, Joseph. (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Page 82.

- ^ Jan Campbell (2005). "Film and cinema spectatorship: melodrama and mimesis". Polity. p.114. ISBN 0-7456-2930-X

- ^ The Camera Obscura : Aristotle to Zahn

- ^ Renner, Eric (1999). Pinhole photography. Oxford, England: Focal Press. pp. 6–8. ISBN 0-240-80350-7.

- ^ Renner (1999: 12)

- ^ Gernsheim, Helmut (1965). A Concise History of Photography. London: Thames and Hudson. pp. 3–6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Newhall, Beaumont (1982). The History of Photography. New York, New York: The Museum of Modern Art. p. 13. ISBN 0-87070-381-1.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, of Chalon-su-Saône in central France, was more successful. Niépce built on a discovery by Johann Heinrich Schultz (1724): that silver salts darken under exposure to light. Although the only example of his camera work that remains today appears to have been made in 1826, his letters leave no doubt that he had succeeded in fixing the camera's image a decade earlier.

- ^ Leslie Stroebel and Richard D. Zakia (1993). The Focal encyclopedia of photography (3rd ed.). Focal Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-240-51417-8.

- ^ Davenport, Alma (1999). The history of photography: an overview. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-8263-2076-7.

- ^ a b Wade, John (1979). A Short History of the Camera. Watford: Fountain Press. ISBN 0-85242-640-2.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ US 3540011

- ^ US 4057830 and US 4163256 were filed in 1972 but were only later awarded in 1976 and 1977. "1970s". Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "Digital Photography Milestones from Kodak". Women in Photography International. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Kodak blog: We Had No Idea".

- ^ Michael R. Peres (2007). The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography (4th ed. ed.). Focal Press. ISBN 0-240-80740-5.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Kenji Toyoda (2006). "Digital Still Cameras at a Glance". In Junichi Nakamura (ed.). Image sensors and signal processing for digital still cameras. CRC Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8493-3545-7.

- ^ Askey, Phil (2001). "Silicon Film – vaporized-ware". Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- ^ "1990". DigiCam History Dot Com. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- ^ "Dycam Model 1: The world's first consumer digital still camera". DigiBarn computer museum.

- ^ Carolyn Said, "DYCAM Model 1: The first portable Digital Still Camera", MacWeek, vol. 4, No. 35, 16 Oct. 1990, p. 34.