Al Hirschfeld: Difference between revisions

m Addition of a fact to the information already appearing |

→Nina: addition citation and of information further clarifying text already present |

||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

In 1943, Hirschfeld married one of Europe's most famous actresses, the late [[Dolly Haas]]. They were married for more than 50 years and in 1945, produced a daughter, Nina.<ref name="Show Business" /> |

In 1943, Hirschfeld married one of Europe's most famous actresses, the late [[Dolly Haas]]. They were married for more than 50 years and in 1945, produced a daughter, Nina.<ref name="Show Business" /> |

||

Hirschfeld is known for hiding Nina's name in most of the drawings he produced after her birth. The name would appear in a sleeve, in a hairdo, or somewhere in the background. As Margo Feiden described it, Hirschfeld engaged in the “harmless insanity,” as he called it, of hiding her name [Nina] at least once in each of his drawings. The number of NINAs concealed is shown by an Arabic numeral to the right of his signature. Generally, if no number is to be found, either NINA appears once or the drawing was executed before she was born.<ref name="Show Business" /> |

Hirschfeld is known for hiding Nina's name in most of the drawings he produced after her birth. The name would appear in a sleeve, in a hairdo, or somewhere in the background. As Margo Feiden described it, Hirschfeld engaged in the “harmless insanity,” as he called it, of hiding her name [Nina] at least once in each of his drawings. The number of NINAs concealed is shown by an Arabic numeral to the right of his signature. Generally, if no number is to be found, either NINA appears once or the drawing was executed before she was born.<ref name="Show Business" /> Almost all of Hirschfeld's limited edition lithographs have NINAs concealed in them. However, the pursuit is made that much harder because there is never a number that would ordinarily tell you how many NINAs there are. |

||

Hirschfeld originally intended the |

For the first few months, Hirschfeld originally intended the hidden NINAs to appeal to his circle of friends. But to Hirschfeld's complete surprise, when he thought the gag had worn thin and tried to stop concealing NINAs in his drawings, what Hirschfeld hadn't realized was that the population at large was beginning to spot them, too. Letters to the New York Times, ranging from "curious" to "furious" pressured Hirschfeld to begin hiding them again. Hirschfeld said it was easier to hide the NINAs than it was to answer all the mail. From time to time Hirschfeld lamented that the gimmick had overshadowed his art. Nina herself was reportedly ambivalent about all the attention the hidden NINAs it brought her.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} |

||

In Hirschfeld's book Show Business is No Business,<ref name="Show Business" /> his art dealer Margo Feiden recounts the following story to illustrate what Hirschfeld meant by “harmless insanity:” "The NINA-counting mania was well illuminated when in 1973 an NYU student kept coming back to my Gallery to stare at the same drawing each day for more than a week. The drawing was Hirschfeld's whimsical portrayal of New York's Central Park. When curiosity finally got the best of me, I asked, ''“What is so riveting about that one drawing that keeps you here for hours, day after day?”'' She answered that she had found only 11 of 39 NINAs and would not give up until all were located. I replied that "the "’39" next to Hirschfeld's signature was the year. Nina was born in 1945." |

|||

| ⚫ | In an interview with ''[[The Comics Journal]]'', Hirschfeld confirmed the [[urban legend]] that the [[United States Army|U.S. Army]] had used his |

||

| ⚫ | In an interview with ''[[The Comics Journal]]'', Hirschfeld confirmed the [[urban legend]] that the [[United States Army|U.S. Army]] had used his drawings to train bomber pilots by assigning soldiers to spot the NINAs much as they would spot their targets. Hirschfeld told the magazine he found the idea repulsive, saying he felt his cartoons were being used to help kill people.{{citation needed|date=February 2013}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In his 1966 anthology ''The World of Hirschfeld'', he included a drawing of Nina which he titled "Nina's Revenge." That drawing contained no NINAs. There were, however, two ALs and two DOLLYs ("The names of her wayward parents").<ref>{{cite book|last=Hirschfeld|first=Al|title=The World of Hirschfeld|year=1970|publisher=Harry N. Abrams|location=New York|isbn=10: 0810901773}}</ref> |

||

===Publications=== |

===Publications=== |

||

Revision as of 23:36, 11 April 2013

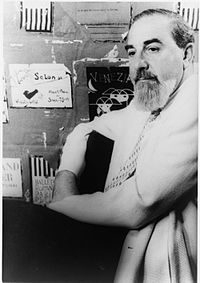

Al Hirschfeld | |

|---|---|

Al Hirschfeld photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1955 | |

| Born | Albert Hirschfeld June 21, 1903 St. Louis, Missouri, USA |

| Died | January 20, 2003 (aged 99) New York City, New York, USA |

| Nationality | United States |

| Education | Art Students League of New York |

| Known for | Painter, caricaturist |

Albert "Al" Hirschfeld (June 21, 1903 – January 20, 2003) was an American caricaturist best known for his simple black and white portraits of celebrities and Broadway stars.

Personal life

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, he moved with his family to New York City, where he received his art training at the Art Students League of New York.

In 1943, he married Dolly Haas (1910–1994); they had one child, a daughter, Nina (b. 1945).

In 1996, he married Louise Kerz, a theatre historian.[1]

Career

In 1924, Hirschfeld traveled to Paris and London, where he studied painting, drawing and sculpture. When he returned to the United States, a friend, fabled Broadway press agent, Richard Maney, showed one of Hirschfeld's drawings to an editor at the New York Herald Tribune, which got Hirschfeld commissions for that newspaper and then, later, The New York Times.

Hirschfeld's art style is unique, and he is considered to be one of the most important figures in contemporary drawing and caricature, having influenced countless artists and cartoonists. His caricatures are almost always drawings of pure line with simple black ink on white paper with little to no shading or crosshatching. His drawings always manage to capture a likeness using the minimum number of lines. Though his caricatures often exaggerate and distort his subjects' faces, he is often described as being a fundamentally "nicer" caricaturist than many of his contemporaries, and being drawn by Hirschfeld was considered an honor more than an insult. Nonetheless he did face some complaints from his editors over the years; in a late-1990s interview with The Comics Journal Hirschfeld recounted how one editor told him his drawings of Broadway's "beautiful people" looked like "a bunch of animals".

He was commissioned by CBS to illustrate a preview magazine featuring the network's new TV programming in fall 1963. One of the programs was Candid Camera, and Hirschfeld's caricature of the show's host Allen Funt outraged Funt so much he threatened to leave the network if the magazine were issued. Hirschfeld prepared a slightly different likeness, perhaps more flattering, but he and the network pointed out to Funt that the artwork prepared for newspapers and some other print media had been long in preparation and it was too late to withdraw it. Funt relented but insisted that what could be changed would have to be. Newsweek ran a squib on the controversy.

Broadway, film, and more

Hirschfeld started young and continued drawing to the end of his life, thus chronicling nearly all the major entertainment figures of the 20th century. During Hirschfeld's nearly eight-decade career, he gained fame by illustrating the actors, singers, and dancers of various Broadway plays, which would appear in advance in The New York Times to herald the play's opening. Though "Theater" was Hirschfeld's best known field of interest, according to his long-time art dealer Margo Feiden, he actually drew more for the movies than he did for live plays. "By the ripe old age of 17, while his contemporaries were learning how to sharpen pencils, Hirschfeld became an art director at Selznick Pictures. He held the position for about four years and then in 1924, he moved to Paris to work, lead the Bohemian life, and grow a beard. This he retained—the beard, not the flat—for the next 80 years, presumably because you never know when your oil burner will go on the fritz." [2]

In addition to Broadway and film, Hirschfeld also drew politicians, TV stars, and celebrities of all stripes from Cole Porter and the Nicholas Brothers to the cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation. Hirschfeld also caricatured jazz musicians—Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald—and rockers The Beatles, Elvis Presley, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Jerry Garcia, and Mick Jagger.[3]

Hirschfeld drew many original movie posters, which include posters for Charlie Chaplin's films, as well as The Wizard of Oz (1939). The "Rhapsody in Blue" segment in the Disney film Fantasia 2000 was inspired by his designs and Hirschfeld became an artistic consultant for the segment; the segment's director, Eric Goldberg, is a longtime fan of his work. Further evidence of Goldberg's admiration for Hirschfeld can be found in Goldberg's character design and animation of the genie in Aladdin (1992). He was the subject of the Oscar-nominated documentary film, The Line King: The Al Hirschfeld Story (1996).

Nina

In 1943, Hirschfeld married one of Europe's most famous actresses, the late Dolly Haas. They were married for more than 50 years and in 1945, produced a daughter, Nina.[2]

Hirschfeld is known for hiding Nina's name in most of the drawings he produced after her birth. The name would appear in a sleeve, in a hairdo, or somewhere in the background. As Margo Feiden described it, Hirschfeld engaged in the “harmless insanity,” as he called it, of hiding her name [Nina] at least once in each of his drawings. The number of NINAs concealed is shown by an Arabic numeral to the right of his signature. Generally, if no number is to be found, either NINA appears once or the drawing was executed before she was born.[2] Almost all of Hirschfeld's limited edition lithographs have NINAs concealed in them. However, the pursuit is made that much harder because there is never a number that would ordinarily tell you how many NINAs there are.

For the first few months, Hirschfeld originally intended the hidden NINAs to appeal to his circle of friends. But to Hirschfeld's complete surprise, when he thought the gag had worn thin and tried to stop concealing NINAs in his drawings, what Hirschfeld hadn't realized was that the population at large was beginning to spot them, too. Letters to the New York Times, ranging from "curious" to "furious" pressured Hirschfeld to begin hiding them again. Hirschfeld said it was easier to hide the NINAs than it was to answer all the mail. From time to time Hirschfeld lamented that the gimmick had overshadowed his art. Nina herself was reportedly ambivalent about all the attention the hidden NINAs it brought her.[citation needed]

In Hirschfeld's book Show Business is No Business,[2] his art dealer Margo Feiden recounts the following story to illustrate what Hirschfeld meant by “harmless insanity:” "The NINA-counting mania was well illuminated when in 1973 an NYU student kept coming back to my Gallery to stare at the same drawing each day for more than a week. The drawing was Hirschfeld's whimsical portrayal of New York's Central Park. When curiosity finally got the best of me, I asked, “What is so riveting about that one drawing that keeps you here for hours, day after day?” She answered that she had found only 11 of 39 NINAs and would not give up until all were located. I replied that "the "’39" next to Hirschfeld's signature was the year. Nina was born in 1945."

In an interview with The Comics Journal, Hirschfeld confirmed the urban legend that the U.S. Army had used his drawings to train bomber pilots by assigning soldiers to spot the NINAs much as they would spot their targets. Hirschfeld told the magazine he found the idea repulsive, saying he felt his cartoons were being used to help kill people.[citation needed]

In his 1966 anthology The World of Hirschfeld, he included a drawing of Nina which he titled "Nina's Revenge." That drawing contained no NINAs. There were, however, two ALs and two DOLLYs ("The names of her wayward parents").[4]

Publications

Al Hirschfeld famously contributed to The New York Times for more than seven decades. His work also appeared in The New York Herald Tribune, The old World, The New Yorker Magazine, Colliers, The American Mercury, TV Guide, Playbill, New York Magazine, and Rolling Stone. Countless other publications included Hirschfeld's drawings and lithographs to illustrate their interviews with him.

In 1941, Hyperion Books published Harlem As Seen By Hirschfeld, with text by William Saroyan.[citation needed]

Hirschfeld's illustrations for the theater were gathered and published yearly in the books, The Best Plays of ... (for example, The Best Plays of 1958-1959).[citation needed]

Books of collections of Hirschfeld's illustrations include Manhattan Oasis, Show Business Is No Business (1951), American Theater, The American Theater as Seen by Al Hirschfeld, The Entertainers (1977), Hirschfeld by Hirschfeld (1979), The World of Al Hirschfeld (1970), The Lively Years, 1920-1973, text by Brooks Atkinson, Hirschfeld’s World (1981), Show Business is No Business, Preface and Endnotes by Margo Feiden (1983), A Selection of Limited Edition Etchings and Lithographs, text by Margo Feiden (1983), Art and Recollections From Eight Decades (1991), Hirschfeld On Line (2000) (Regular Edition and Deluxe Edition), Hirschfeld’s Hollywood (2001), Hirschfeld’s New York (2001), Hirschfeld’s Speakeasies of 1932, Introduction by Pete Hammill (2003), Hirschfeld’s Harlem, and Hirschfeld’s British Isles (2005).

Hirschfeld collaborated with humorist S. J. Perelman on several publications, including Westward Ha! Or, Around the World in 80 Clichés, a satirical look at the duo's travels on assignment for Holiday magazine. In 1991, the United States Postal Service commissioned Hirschfeld to draw a series of postage stamps commemorating famous American comedians. The collection included drawings of Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy, Edgar Bergen (with Charlie McCarthy), Jack Benny, Fanny Brice, Bud Abbott, and Lou Costello. He followed that with a collection of silent film stars including Rudolph Valentino, ZaSu Pitts and Buster Keaton. The Postal Service allowed him to include Nina's name in his drawings, waiving their own rule forbidding hidden messages in United States stamp designs.

Hirschfeld expanded his audience by contributing to Patrick F. McManus' humor column in Outdoor Life magazine for a number of years.

Collections and tributes

Permanent collections of Hirschfeld's work are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Permanent collection at the Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd., seventy-five years of Hirschfeld's original drawings, limited edition lithographs and etchings, archives.

The Martin Beck Theatre, which opened November 11, 1924 at 302 West 45th Street, was renamed to become the Al Hirschfeld Theatre on June 21, 2003. It reopened on November 23, 2003 with a revival of the musical Wonderful Town. Hirschfeld was also honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

In 2002, Al Hirschfeld was awarded the National Medal of Arts.[5]

Key to those caricatured in the illustration, right: The Algonquin Round Table. Seated clockwise) around the table are Robert Sherwood (wineglass in hand), Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Alexander Woollcott, Heywood Broun, Marc Connelly, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, and George S. Kaufman. At table in left background are Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt, with Frank Crowninshield standing. In background at right is Frank Case, owner of the Algonquin Hotel.

Death

Hirschfeld resided at 122 East 95th Street, in Manhattan. He died, aged 99, of natural causes at his home on January 20, 2003.[citation needed] His first wife, Broadway actress/performer Dolly Haas, had died from ovarian cancer in 1994, aged 84.

Hirschfeld's desk, lamp and chair were donated to The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and are on display in the lobby.

See also

References

- ^ [1] NY Times Wedding Notice

- ^ a b c d Show Business is No Business (1983). New York: Da Capo Press, pp. Endnotes, ISBN=10:0306762218

- ^ "Al Hirschfeld/Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd".

- ^ Hirschfeld, Al (1970). The World of Hirschfeld. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 10: 0810901773.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Lifetime Honors - National Medal of Arts

External links

- Al Hirschfeld Official Site—Margo Feiden Galleries Ltd., New York, wwww.alhirschfeld.com

- official site for the Al Hirschfeld Foundation with database of Hirschfeld artwork

- Al Hirschfeld, Beyond Broadway exhibition at the Library of Congress

- Internet Broadway Database: Al Hirschfeld Theatre details

- St. Louis Walk of Fame

- Jewish American Hall of Fame

- Get Happy - Judy Garland

- Art Directors Club biography, portrait and images of work