Bomb: Difference between revisions

Tag: section blanking |

Mytwocents (talk | contribs) Undid revision 561095605 by 182.19.30.169 (talk) |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

Below is a list of five different types of bombs based on the fundamental explosive mechanism they employ. |

Below is a list of five different types of bombs based on the fundamental explosive mechanism they employ. |

||

===Compressed Gas=== |

|||

Relatively small explosions can be produced by pressurizing a container until catastrophic failure such as with a [[dry ice bomb]]. Technically, devices that create explosions of this type can not be classified as "bombs" by the definition presented at the top of this article. However, the explosions created by these devices can cause property damage, injury, or death. Flammable liquids, gasses and gas mixtures dispersed in these explosions may also ignite if exposed to a spark or flame. |

|||

===Low Explosive=== |

===Low Explosive=== |

||

Revision as of 21:04, 22 June 2013

A bomb is any of a range of explosive weapons that only rely on the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy (an explosive device). Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanical stress, the impact and penetration of pressure-driven projectiles, pressure damage, and explosion-generated effects.[1] A nuclear weapon employs chemical-based explosives to initiate a much larger nuclear-based explosion. Bombs have been in use since the 11th century in Song Dynasty China.[2]

The term bomb is not usually applied to explosive devices used for civilian purposes such as construction or mining, although the people using the devices may sometimes refer to them as "bomb". The military use of the term "bomb", or more specifically aerial bomb action, typically refers to airdropped, unpowered explosive weapons most commonly used by air forces and naval aviation. Other military explosive weapons not classified as "bombs" include grenades, shells, depth charges (used in water), warheads when in missiles, or land mines. In unconventional warfare, "bomb" can refer to a range of offensive weaponry. For instance, in recent conflicts, "bombs" known as improvised explosive devices (IEDS) have been employed by insurgent fighters to great effectiveness.

The word comes from the Latin bombus, which in turn comes from the Greek βόμβος (bombos),[3] an onomatopoetic term meaning "booming", "buzzing".

History

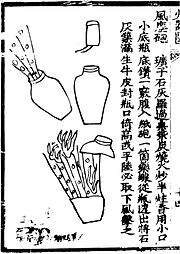

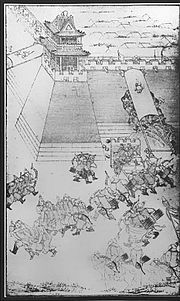

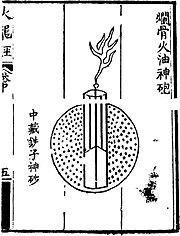

Explosive bombs were used in China in 1221, by a Jin Dynasty army against a Song Dynasty city. Bombs built using bamboo tubes appear in the 11th century.[2] Bombs made of cast iron shells packed with explosive gunpowder date to 13th century China.[6] The term was coined for this bomb (i.e. "thunder-crash bomb") during a Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) naval battle of 1231 against the Mongols.[6] The History of Jin 《金史》 (compiled by 1345) states that in 1232, as the Mongol general Subutai (1176–1248) descended on the Jin stronghold of Kaifeng, the defenders had a "thunder-crash bomb" which "consisted of gunpowder put into an iron container ... then when the fuse was lit (and the projectile shot off) there was a great explosion the noise whereof was like thunder, audible for more than a hundred li, and the vegetation was scorched and blasted by the heat over an area of more than half a mou. When hit, even iron armour was quite pierced through."[6] The Song Dynasty (960–1279) official Li Zengbo wrote in 1257 that arsenals should have several hundred thousand iron bomb shells available and that when he was in Jingzhou, about one to two thousand were produced each month for dispatch of ten to twenty thousand at a time to Xiangyang and Yingzhou.[6] The Ming Dynasty text Huolongjing describes the use of poisonous gunpowder bombs, including the "wind-and-dust" bomb.[4]

During the Mongol invasions of Japan, the Mongols used the explosive "thunder-crash bombs" against the Japanese. Archaeological evidence of the "thunder-crash bombs" has been discovered in an underwater shipwreck off the shore of Japan by the Kyushu Okinawa Society for Underwater Archaeology. X-rays by Japanese scientists of the excavated shells confirmed that they contained gunpowder.[7]

Shock

Explosive shock waves can cause situations such as body displacement (i.e., people being thrown through the air), dismemberment, internal bleeding and ruptured eardrums.[8]

Shock waves produced by explosive events have two distinct components, the positive and negative wave. The positive wave shoves outward from the point of detonation, followed by the trailing vacuum space "sucking back" towards the point of origin as the shock bubble collapses. The greatest defense against shock injuries is distance from the source of shock.[9] As a point of reference, the overpressure at the Oklahoma City bombing was estimated in the range of 28 MPa.[10]

Heat

A thermal wave is created by the sudden release of heat caused by an explosion. Military bomb tests have documented temperatures of up to 2,480 °C (4,500 °F). While capable of inflicting severe to catastrophic burns and causing secondary fires, thermal wave effects are considered very limited in range compared to shock and fragmentation. This rule has been challenged, however, by military development of thermobaric weapons, which employ a combination of negative shock wave effects and extreme temperature to incinerate objects within the blast radius. This would be fatal to humans, as bomb tests have proven.

Fragmentation

Fragmentation is produced by the acceleration of shattered pieces of bomb casing and adjacent physical objects. The use of fragmentation in bombs dates to the 14th century, and appears in the Ming Dynasty text Huolongjing. The fragmentation bombs were filled with iron pellets and pieces of broken porcelain. Once the bomb explodes, the resulting shrapnel is capable of piercing the skin and blinding enemy soldiers.[11]

While conventionally viewed as small metal shards moving at super- to hypersonic speeds, fragmentation can occur in epic proportions and travel for extensive distances. When the S.S. Grandcamp exploded in the Texas City Disaster on April 16, 1947, one fragment of that blast was a two ton anchor which was hurled nearly two miles inland to embed itself in the parking lot of the Pan American refinery. Fragmentation should not be confused with shrapnel, which relies on the momentum of a shell to cause damage.

Effects on living things

To people who are close to a blast incident, such as bomb disposal technicians, soldiers wearing body armor, deminers or individuals wearing little to no protection, there are four types of blast effects on the human body: overpressure (shock), fragmentation, impact and heat. Overpressure refers to the sudden and drastic rise in ambient pressure that can damage the internal organs, possibly leading to permanent damage or death. Fragmentation includes the shrapnel described above but can also include sand, debris and vegetation from the area surrounding the blast source. This is very common in anti-personnel mine blasts.[12] The projection of materials poses a potentially lethal threat caused by cuts in soft tissues, as well as infections, and injuries to the internal organs. When the overpressure wave impacts the body it can induce violent levels of blast-induced acceleration. Resulting injuries range from minor to unsurvivable. Immediately following this initial acceleration, deceleration injuries can occur when a person impacts directly against a rigid surface or obstacle after being set in motion by the force of the blast. Finally, injury and fatality can result from the explosive fireball as well as incendiary agents projected onto the body. Personal protective equipment, such as a bomb suit or demining ensemble, as well as helmets, visors and foot protection, can dramatically reduce the four effects, depending upon the charge, proximity and other variables.

Effects on structures

Types

Experts commonly distinguish between civilian and military bombs. The latter are almost always mass-produced weapons, developed and constructed to a standard design out of standard components and intended to be deployed in a standard explosive device. IEDs are divided into three basic categories by basic size and delivery. Type 76, IEDs are hand-carried parcel or suitcase bombs, type 80, are "suicide vests" worn by a bomber, and type 3 devices are vehicles laden with explosives to act as large-scale stationary or self-propelled bombs, also known as VBIED (vehicle-borne IEDs).[citation needed]

Improvised explosive materials are typically very unstable [citation needed] and subject to spontaneous, unintentional detonation triggered by a wide range of environmental effects ranging from impact and friction to electrostatic shock. Even subtle motion, change in temperature, or the nearby use of cellphones or radios, can trigger an unstable or remote-controlled device. Any interaction with explosive materials or devices by unqualified personnel should be considered a grave and immediate risk of death or dire injury. The safest response to finding an object believed to be an explosive device is to get as far away from it as possible.

Atomic bombs are based on the theory of nuclear fission, that when a large atom splits it releases a massive amount of energy. Hydrogen bombs use the energy from an initial fission explosion to create an even more powerful fusion explosion.

The term dirty bomb refers to a specialized device that relies on a comparatively low explosive yield to scatter harmful material over a wide area. Most commonly associated with radiological or chemical materials, dirty bombs seek to kill or injure and then to deny access to a contaminated area until a thorough clean-up can be accomplished. In the case of urban settings, this clean-up may take extensive time, rendering the contaminated zone virtually uninhabitable in the interim.

The power of large bombs is typically measured in kilotons (Kt) or megatons of TNT (Mt). The most powerful bombs ever used in combat were the two atomic bombs dropped by the United States to attack Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the most powerful ever tested was the Tsar Bomba. The most powerful non-nuclear bomb is Russian "Father of All Bombs" (officially Aviation Thermobaric Bomb of Increased Power (ATBIP))[13] followed by the United States Air Force's MOAB (officially Massive Ordnance Air Blast, or more commonly known as the "Mother of All Bombs").

Below is a list of five different types of bombs based on the fundamental explosive mechanism they employ.

Compressed Gas

Relatively small explosions can be produced by pressurizing a container until catastrophic failure such as with a dry ice bomb. Technically, devices that create explosions of this type can not be classified as "bombs" by the definition presented at the top of this article. However, the explosions created by these devices can cause property damage, injury, or death. Flammable liquids, gasses and gas mixtures dispersed in these explosions may also ignite if exposed to a spark or flame.

Low Explosive

The simplest and oldest type of bombs store energy in the form of a low explosive. Black powder is an example of a low explosive. Low explosives typically consist of a composition of an oxidizing salt, such as potassium nitrate, and solid fuel, such as charcoal or aluminum powder. These compositions deflagrate upon ignition producing hot gas. Under normal circumstances deflagration occurs too slowly to produce a significant pressure wave. Low explosives must, therefore, be used in large quantities or confined in a container with a high burst pressure to be used as a bomb.

High Explosive

A high explosive bomb is one that employs a process called "detonation" to rapidly release its chemical energy. Detonation is distinct from deflagration in that the chemical reaction propagates faster than the speed of sound (often many times faster) in an intense shock wave. Therefore, the pressure wave produced by a high explosive is not significantly increased by confinement as detonation occurs so quickly that the resulting plasma does not expand much before all the explosive material has reacted. This has led to the development of plastic explosive. A casing is still employed in some high explosive bombs, but with the purpose of fragmentation. Most high explosive bombs consist of an insensitive secondary explosive that must be detonated with a blasting cap containing a more sensitive primary explosive.

Nuclear Fission

Nuclear fission type atomic bombs utilize the energy present in very heavy atomic nuclei, such as U-235 or Pu-239. In order to release this energy rapidly, a certain amount of the fissile material must be very rapidly consolidated while being exposed to a neutron source. If consolidation occurs slowly, repulsive forces drive the material apart before a significant explosion can occur. Under the right circumstances, rapid consolidation can provoke a chain reaction that can proliferate and intensify by many orders of magnitude within microseconds. The energy released by a nuclear fission bomb may be tens of thousands of times greater than a chemical bomb of the same mass.

Nuclear Fusion

Nuclear fusion type atomic bombs release energy through the fusion of the light atomic nuclei of deuterium and tritium. With this type of bomb, a thermonuclear detonation is triggered by the detonation of a fission type nuclear bomb contained within a material containing high concentrations of deuterium and tritium. Weapon yield is typically increased with a tamper that increases the duration and intensity of the reaction through inertial confinement and neutron reflection. Nuclear fusion bombs can have arbitrarily high yields making them hundreds or thousands of times more powerful than nuclear fission bombs.

Delivery

The first air-dropped bombs were used by the Austrians in the 1849 siege of Venice. Two hundred unmanned balloons carried small bombs although few bombs actually hit the city.[14]

The first bombing from a fixed-wing aircraft took place in 1911 when the Italians bombed the Turkish lines in what is now Libya, during the Italo-Turkish War. The bombs were dropped by hand.[15]

The first large scale dropping of bombs took place during World War I starting in 1915 with the German Zeppelin Airship raids on London, England. One raid on the 8th of September 1915 dropped 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) of high explosives and incendiary bombs, including one bomb which weighed 600 lb (270 kg).[16]

The first significant bombing in the United States took place nine years later at noon on September 16, 1920 when an explosives-laden horse-drawn wagon detonated on the lunchtime-crowded streets of New York's financial district. The Wall Street bombing employed many aspects of modern VNSA devices, such as cast-iron slugs added for shrapnel, in an attack that killed 38 and injured some 400 others.

Modern military bomber aircraft are designed around a large-capacity internal bomb bay while fighter bombers usually carry bombs externally on pylons or bomb racks, or on multiple ejection racks which enable mounting several bombs on a single pylon. Modern bombs, precision-guided munitions, may be guided after they leave an aircraft by remote control, or by autonomous guidance. When bombs such as nuclear weapons are mounted on a powered platform, they are called guided missiles.

Some bombs are equipped with a parachute, such as the World War II "parafrag", which was an 11 kg fragmentation bomb, the Vietnam war-era daisy cutters, and the bomblets of some modern cluster bombs. Parachutes slow the bomb's descent, giving the dropping aircraft time to get to a safe distance from the explosion. This is especially important with airburst nuclear weapons, and in situations where the aircraft releases a bomb at low altitude.[17]

A hand grenade is delivered by being thrown. Grenades can also be projected by other means, such as being launched from the muzzle of a rifle, as in the rifle grenade or using the M203 grenade launcher or by attaching a rocket to the explosive grenade as in a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG).

A bomb may also be positioned in advance and concealed.

A bomb destroying a rail track just before a train arrives causes a train to derail. Apart from the damage to vehicles and people, a bomb exploding in a transport network often also damages, and is sometimes mainly intended to damage that network. This applies for railways, bridges, runways, and ports, and to a lesser extent, depending on circumstances, to roads.

In the case of suicide bombing the bomb is often carried by the attacker on his or her body, or in a vehicle driven to the target.

The Blue Peacock nuclear mines, which were also termed "bombs", were planned to be positioned during wartime and be constructed such that, if they were disturbed, they would explode within ten seconds.

The explosion of a bomb may be triggered by a detonator or a fuse. Detonators are triggered by clocks, remote controls like cell phones or some kind of sensor, such as pressure (altitude), radar, vibration or contact. Detonators vary in ways they work, they can be electrical, fire fuze or blast initiated detonators and others,

Blast seat

In forensic science, the point of detonation of a bomb is referred to as its blast seat, seat of explosion, blast hole or epicenter. Depending on the type, quantity and placement of explosives, the blast seat may be either spread out or concentrated (i.e., an explosion crater).[18]

Other types of explosions, such as dust or vapor explosions, do not cause craters or even have definitive blast seats.[18]

References

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2007) |

- ^ Milstein, Randall L. (2008). "Bomb damage assessment". In Ayn Embar-seddon, Allan D. Pass (eds.) (ed.). Forensic Science. Salem Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-58765-423-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Peter Connolly (1 November 1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare. Taylor & Francis. p. 356. ISBN 978-1-57958-116-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ βόμβος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ a b Joseph Needham (1986). Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ^ Joseph Needham (1974). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology : the gunpowder epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ^ a b c d Needham, Joseph. (1987). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 170-174.

- ^ Delgado, James (2003). "Relics of the Kamikaze". Archaeology. 56 (1). Archaeological Institute of America.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mlstein, Randall L. (2008). "Bomb damage assessment". In Ayn Embar-seddon, Allan D. Pass (eds.) (ed.). Forensic Science. Salem Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-58765-423-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ Marks, Michael E. (2002). The Emergency Responder's Guide to Terrorism. Red Hat Publishing Co., Inc. p. 30. ISBN 1-932235-00-0.

- ^ Wong, Henry (2002). "Blast-Resistant Building Design Technology Analysis of its Application to Modern Hotel Design". WGA Wong Gregerson Architects, Inc. p. 5.

- ^ Joseph Needham (1986). Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–181. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- ^ Coupland, R.M. (1989). Amputation for antipersonnel mine injuries of the leg: preservation of the tibial stump using a medial gastrocnemius myoplasty. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 71, pp. 405–408.

- ^ Solovyov, Dmitry (2007-09-12). "Russia tests superstrength bomb, military says". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ Murphy, Justin (2005). Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918: An Illustrated History of their Impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 10. ISBN 1-85109-488-1. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindqvist, Sven (2004). "Guernica". Shock and Awe: War on Words. published by Van Eekelen, Bregje. North Atlantic Books. p. 76. ISBN 0-9712546-0-5. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Wilbur Cross, "Zeppelins of World War I" page 35, published 1991 Paragon House ISBN I-56619-390-7

- ^ Jackson, S.B. (June 1968). "The Retardation of Weapons for Low Altitude Bombing". United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Walsh, C. J. (2008). "Blast seat". In Ayn Embar-seddon, Allan D. Pass (eds.) (ed.). Forensic Science. Salem Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-58765-423-7.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)

External links

- Explosive Violence, The Problem of Explosive Weapons A report by Richard Moyes (Landmine Action, 2009) on the humanitarian problems caused by the use of bombs and other explosive weapons in populated areas

- FAS.org Bombs for Beginners

- MakeItLouder.com How a bomb functions and rating their power