Adam Weishaupt: Difference between revisions

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

==Founder of the Illuminati== |

==Founder of the Illuminati== |

||

On |

On May day 1776 Weishaupt formed the "Order of Illuminati". He adopted the name of "Brother [[Spartacus]]" within the order. Although the Order was not [[egalitarian]] or democratic internally, it sought to promote the doctrines of equality and freedom throughout society.<ref name="Catholic Encyclopedia">Catholic Encyclopedia: [http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07661b.htm Illuminati], sourcing Illuminati papers</ref> |

||

The actual character of the society was an elaborate network of spies and counter-spies. Each isolated cell of initiates reported to a superior, whom they did not know, a party structure that was effectively adopted by some later groups.<ref name="Catholic Encyclopedia" /> |

The actual character of the society was an elaborate network of spies and counter-spies. Each isolated cell of initiates reported to a superior, whom they did not know, a party structure that was effectively adopted by some later groups.<ref name="Catholic Encyclopedia" /> |

||

Revision as of 11:16, 12 December 2013

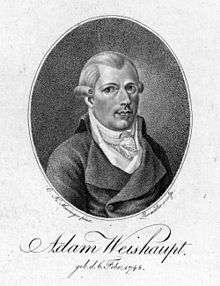

Johann Adam Weishaupt | |

|---|---|

Adam Weishaupt | |

| Born | 6 February 1748 |

| Died | 18 November 1830 (aged 82) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Empiricism |

Main interests | Epistemology, Metaphysics, Ethics |

Johann Adam Weishaupt (6 February 1748 – 18 November 1830[1][2][3][4]) was a German philosopher and founder of the Order of Illuminati, a secret society with origins in Bavaria.

Early life

Adam Weishaupt was born on 6 February 1748 in Ingolstadt[1][5] in the Electorate of Bavaria. Weishaupt's father Johann Georg Weishaupt (1717–1753) died[5] when Adam was five years old. After his father's death he came under the tutelage of his godfather Johann Adam Freiherr von Ickstatt[6] who, like his father, was a professor of law at the University of Ingolstadt.[7] Ickstatt was a proponent of the philosophy of Christian Wolff and of the Enlightenment,[8] and he influenced the young Weishaupt with his rationalism. Weishaupt began his formal education at age sevenCite error: The <ref> tag has too many names (see the help page). at a Jesuit school. He later enrolled at the University of Ingolstadt and graduated in 1768[9] at age 20 with a doctorate of law.[10] In 1772[11] he became a professor of law. The following year he married Afra Sausenhofer[12] of Eichstätt.

After Pope Clement XIV’s suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773, Weishaupt became a professor of canon law,[13] a position that was held exclusively by the Jesuits until that time. In 1775 Weishaupt was introduced[14] to the empirical philosophy of Johann Georg Heinrich Feder[15] of the University of Göttingen. Both Feder and Weishaupt would later become opponents of Kantian idealism.[16]

Founder of the Illuminati

On May day 1776 Weishaupt formed the "Order of Illuminati". He adopted the name of "Brother Spartacus" within the order. Although the Order was not egalitarian or democratic internally, it sought to promote the doctrines of equality and freedom throughout society.[17]

The actual character of the society was an elaborate network of spies and counter-spies. Each isolated cell of initiates reported to a superior, whom they did not know, a party structure that was effectively adopted by some later groups.[17]

Weishaupt was initiated into the Masonic Lodge "Theodor zum guten Rath", at Munich in 1777. His project of "illumination, enlightening the understanding by the sun of reason, which will dispel the clouds of superstition and of prejudice" was an unwelcome reform.[17] Soon however he had developed gnostic mysteries of his own[citation needed], with the goal of "perfecting human nature" through re-education to achieve a communal state with nature, freed of government and organized religion. He began working towards incorporating his system of Illuminism with that of Freemasonry.[17]

Weishaupt's radical rationalism and vocabulary was not likely to succeed. Writings that were intercepted in 1784 were interpreted as seditious, and the Society was banned by the government of Karl Theodor, Elector of Bavaria, in 1784. Weishaupt lost his position at the University of Ingolstadt and fled Bavaria.[17]

Activities in exile

He received the assistance of Duke Ernest II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1745–1804), and lived in Gotha writing a series of works on illuminism, including A Complete History of the Persecutions of the Illuminati in Bavaria (1785), A Picture of Illuminism (1786), An Apology for the Illuminati (1786), and An Improved System of Illuminism (1787). Adam Weishaupt died in Gotha on 18 November 1830.[1][2][3][4] He was survived by his second wife, Anna Maria (née Sausenhofer), and his children Nanette, Charlotte, Ernst, Karl, Eduard, and Alfred.[2] Weishaupt was buried next to his son Wilhelm who preceded him in death in 1802.

After Weishaupt's Order of the Illuminati was banned and its members dispersed, it left behind no enduring traces of an influence, not even on its own erstwhile members, who went on in the future to develop in quite different directions.[18]

References in pop culture

Adam Weishaupt is referred to repeatedly in The Illuminatus! Trilogy, written by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, as the founder of the Bavarian Illuminati and as an imposter who killed George Washington and took his place as the first president of the United States. Washington's portrait on the U.S. one-dollar bill is said to actually be Weishaupt's.

Another version of Adam Weishaupt appears in the extensive comic book novel Cerebus the Aardvark by Dave Sim, as a combination of Weishaupt and George Washington. He appears primarily in the Cerebus and Church & State I volumes. His motives are republican confederalizing of city-states in Estarcion (a pseudo-Europe) and the accumulation of capital unencumbered by government or church.

Weishaupt's name is one of many references made to the Illuminati and other conspiracies in the 2000 PC game Deus Ex. During JC Denton's escape from Versalife labs in Hong Kong, he recovers a virus engineered with the molecular structure in multiples of 17 and 23. Tracer Tong notes "1723... the birthdate of Adam Weishaupt" even though this reference is actually incorrect: Weishaupt was born in 1748.

Adam Weishaupt is also mentioned ("Bush got a ouija to talk to Adam Weishaupt") by the New York rapper Cage in El-P's "Accidents Don't Happen", the ninth track on his album Fantastic Damage (2002).

Adam Weishaupt is briefly mentioned in Umberto Eco's novel The Prague Cemetery.[19]

Works

Philosophical works

- (1775) De Lapsu Academiarum Commentatio Politica.

- (1786) Über die Schrecken des Todes – eine philosophische Rede.

- Template:Fr icon Discours Philosophique sur les Frayeurs de la Mort (1788). Gallica

- (1786) Über Materialismus und Idealismus. Torino

- (1788) Geschichte der Vervollkommnung des menschlichen Geschlechts.

- (1788) Über die Gründe und Gewißheit der Menschlichen Erkenntniß.

- (1788) Über die Kantischen Anschauungen und Erscheinungen.

- (1788) Zweifel über die Kantischen Begriffe von Zeit und Raum.

- (1793) Über Wahrheit und sittliche Vollkommenheit.

- (1794) Über die Lehre von den Gründen und Ursachen aller Dinge.

- (1794) Über die Selbsterkenntnis, ihre Hindernisse und Vorteile.

- (1797) Über die Zwecke oder Finalursachen.

- (1802) Über die Hindernisse der baierischen Industrie und Bevölkerung.

- (1804) Die Leuchte des Diogenes.

- Template:En icon Diogenes Lamp (Tr. Amelia Gill) introduced by Sir Mark Bruback chosen by the Masonic Book Club to be its published work for 2008. (Ed. Andrew Swanlund).

- (1817) Über die Staats-Ausgaben und Auflagen. Google Books

- (1818) Über das Besteuerungs-System.

Notes

- ^ a b c Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 41, p. 539.

- ^ a b c Engel, Leopold. Geschichte des Illuminaten-ordens. Berlin: H. Bermühler Verlag, 1906.

- ^ a b van Dülmen, Richard. Der Geheimbund der Illuminaten. Stuttgart: Frommann-Holzboog, 1975.

- ^ a b Stauffer, Vernon. New England and the Bavarian Illuminati. Columbia University, 1918.

- ^ a b Engel 22.

- ^ Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 13, pp. 740–741.

- ^ Freninger, Franz Xaver, ed. Das Matrikelbuch der Universitaet Ingolstadt-Landshut-München. München: A. Eichleiter, 1872. 31.

- ^ Hartmann, Peter Claus. Bayerns Weg in die Gegenwart. Regensburg: Pustet, 1989. 262. Also, Bauerreiss, Romuald. Kirchengeschichte Bayerns. Vol. 7. St. Ottilien: EOS Verlag, 1970. 405.

- ^ Freninger 47.

- ^ Engel 25–28.

- ^ Freninger 32.

- ^ Engel 31.

- ^ Engel 33. Also, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 41, p. 540.

- ^ Engel 61–62.

- ^ Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 6, pp. 595–597.

- ^ Beiser, Frederick C. The Fate of Reason. Harvard University Press, 1987. 186–88.

- ^ a b c d e Catholic Encyclopedia: Illuminati, sourcing Illuminati papers

- ^ Dr. Eberhard Weis in Die Weimarer Klassik und ihre Geheimbünde, edited by Professor Walter Müller-Seidel and Professor Wolfgang Riedel, Königshausen und Neumann, 2003, pp. 100-101

- ^ Umberto Eco, The Prague Cemetery (Boston and New York 2011), 49.

External links

- Template:De icon Biography in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie Vol. 41, pp. 539–550 by Daniel Jacoby.

- A Bavarian Illuminati primer by Trevor W. McKeown.

- Illuminati entry in The Catholic Encyclopedia, hosted by New Advent.