Societal impacts of cars: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 98.216.150.131 to version by Jim.henderson. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1759501) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

Over time, the car has evolved beyond being a means of transportation or status symbol and into a subject of interest and a cherished hobby amongst many people in the world, who appreciate cars for their craftsmanship, their performance, as well as the vast arrays of [[car club|activities]] one can take part in with his/her car.<ref> http://www.aaca.org/About-AACA/an-introduction-to-aaca.html. ''A Concise History of AACA in the Beginning''. Antique Automobile Club of America. Retrieved on February 20, 2014</ref> People who have a keen interest in cars and/or participate in the car hobby are known as "Car Enthusiasts". |

Over time, the car has evolved beyond being a means of transportation or status symbol and into a subject of interest and a cherished hobby amongst many people in the world, who appreciate cars for their craftsmanship, their performance, as well as the vast arrays of [[car club|activities]] one can take part in with his/her car.<ref> http://www.aaca.org/About-AACA/an-introduction-to-aaca.html. ''A Concise History of AACA in the Beginning''. Antique Automobile Club of America. Retrieved on February 20, 2014</ref> People who have a keen interest in cars and/or participate in the car hobby are known as "Car Enthusiasts". |

||

One major aspect of the hobby is collecting, cars, especially classic vehicles, are appreciated by their owners as having aesthetic, recreational and historic value. <ref> http://www.wealthdaily.com/articles/investing-in-classic-cars/4748. ''Investing in classic cars''. Retrieved on April 5, 2014</ref>. Such demand generates investment potential and allows some cars to command extraordinarily high prices and become financial instruments in their own right. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Another major aspect of the hobby is driving events, where enthusiasts from around the world gather to drive and race their cars. Notable examples such events are the annual [[Mille Miglia]] classic car rally and the [[Gumball 3000]] supercar race. |

|||

| ⚫ | Many [[car club|car clubs]] have been set up to facilitate social interactions and companionships amongst those who take pride in owning, maintaining, driving and showing their cars. Many prestigious social events around the world today are centered around the hobby, a notable example is the [[Pebble_Beach_Concours_d%27Elegance|Pebble Beach Concours D'Elegance]] classic car show. |

||

===Safety=== |

===Safety=== |

||

Revision as of 00:29, 6 April 2014

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2010) |

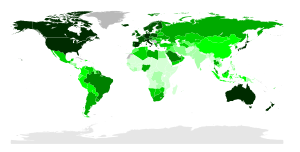

Over the course of the 20th century, the automobile rapidly developed from an expensive toy for the rich into the de facto standard for passenger transport in most developed countries.[1] In developing countries, the effects of the automobile have lagged, but are emulating the impacts of developed nations. The development of the automobile built upon the transport revolution started by railways, and like the railways, introduced sweeping changes in employment patterns, social interactions, infrastructure and goods distribution.

The effects of the automobile on everyday life have been a subject of controversy. While the introduction of the mass-produced automobile represented a revolution in mobility and convenience, the modern consequences of heavy automotive use contribute to the use of non-renewable fuels, a dramatic increase in the rate of accidental death, social isolation, the disconnection of community, the rise in obesity, the generation of air and noise pollution, urban sprawl, and urban decay.[2]

History

When the motor age arrived at the beginning of the 20th century in western countries, many intellectuals started to oppose to the increase of motor-vehicles on roads. The consequences of such increase, were removing space from pedestrians for infrastructures and a tremendous increase in pedestrians fatalities caused by car collisions.

W.S. Gilbert, a British magistrate and intellectual wrote to The Times on 3 June 1903:

- Sir,–I am delighted with the suggestion made by your spirited correspondent Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey that all pedestrians shall be legally empowered to discharge shotguns (the size of the shot to be humanely restricted to No. 8 or No. 9) at all motorists who may appear to them to be driving to the common danger. Not only would this provide a speedy and effective punishment for the erring motorist, but it would also supply the dwellers on popular highroads with a comfortable increase of income. “Motor shooting for a single gun” would appeal strongly to the sporting instincts of the true Briton, and would provide ample compensation to the proprietors of eligible road-side properties for the intolerable annoyance caused by the enemies of mankind.

Access and convenience

Worldwide, the automobile has allowed easier access to remote places. However, average journey times to regularly visited places have increased in large cities, especially in Latin America, as a result of widespread automobile adoption. This is due to traffic congestion and the increased distances between home and work brought about by urban sprawl.[3]

Examples of automobile access issues in underdeveloped countries are:

- Paving of Mexican Federal Highway 1 through Baja California, completing the connection of Cabo San Lucas to California, and convenient access to the outside world for villagers along the route. (occurred in the 1950s)

- In Madagascar, approximately 30 percent of the population does not have access to reliable all weather roads.[4]

- In China, 184 towns and 54,000 villages have no motor road (or roads at all)[5]

- The origin of HIV explosion has been hypothesized by CDC researchers to derive in part from more intensive social interactions afforded by new road networks in Central Africa allowing more frequent travel from villagers to cities and higher density development of many African cities in the period 1950 to 1980.[6]

Certain developments in retail are partially due to automobile use:

- Drive-thru fast food purchasing

- Gasoline station grocery shopping

External costs

According to the Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector[7] made by the Delft University and which is the main reference in European Union for assessing the external costs of automobiles, the main external costs of driving a car are congestion and scarcity costs, accident costs, air pollution costs, noise costs, climate change costs, costs for nature and landscape, costs for soil and water pollution and costs of energy dependency.

Economic changes

The development of the automobile has contributed to changes in employment distribution, shopping patterns, social interactions, manufacturing priorities and city planning; increasing use of automobiles has reduced the roles of walking, horses and railroads.[8]

In addition to money for roadway construction, car use was also encouraged in many places through new zoning laws that required that any new business construct a certain amount of parking based on the size and type of facility. The effect of this was to create a massive quantity of free parking spaces and to push businesses further back from the road. Many shopping centers and suburbs abandoned sidewalks altogether,[9] making pedestrian access dangerous. This had the effect of encouraging people to drive, even for short trips that might have been walkable, thus increasing and solidifying American auto-dependency.[10] As a result of this change, employment opportunities for people who were not wealthy enough to own a car and for people who could not drive, due to age or physical disabilities, became severely limited.[11]

Cultural changes

Prior to the appearance of the automobile, horses, walking and streetcars were the major modes of transportation within cities.[8] Horses require a large amount of care, and were therefore kept in public facilities that were usually far from residences. The wealthy could afford to keep horses for private use, hence the term carriage trade referred to elite patronage.[12] Horse manure left on the streets also created a sanitation problem.[13]

The automobile made regular medium-distance travel more convenient and affordable, especially in areas without railways. Because automobiles did not require rest, were faster than horse-drawn conveyances, and soon had a lower total cost of ownership, more people were routinely able to travel farther than in earlier times. The construction of highways half a century later continued this revolution in mobility. Some experts suggest that many of these changes began during the earlier Golden age of the bicycle, from 1880—1915.[14]

Changes to urban society

Beginning in the 1940s, most urban environments in the United States lost their streetcars, cable cars, and other forms of light rail, to be replaced by diesel-burning motor coaches or buses. Many of these have never returned, though some urban communities eventually installed subways.

Another change brought about by the automobile is that modern urban pedestrians must be more alert than their ancestors. In the past, a pedestrian had to worry about relatively slow-moving streetcars or other obstacles of travel. With the proliferation of the automobile, a pedestrian has to anticipate safety risks of automobiles traveling at high speeds because they can cause serious injuries to a human and can be fatal,[8] unlike in previous times when traffic deaths were usually due to horses escaping control.

According to many social scientists, the loss of pedestrian-scale villages has also disconnected communities. Many people in developed countries have less contact with their neighbors and rarely walk unless they place a high value on exercise.[15]

Advent of suburban society

Improved transport accelerated the outward growth of cities and the development of suburbs beyond an earlier era's streetcar suburbs.[8] Until the advent of the automobile, factory workers lived either close to the factory or in high density communities farther away, connected to the factory by streetcar or rail. The automobile and the federal subsidies for roads and suburban development that supported car culture allowed people to live in low density residential areas even farther from the city center and integrated city neighborhoods.[8] Few suburbs were factory towns, due in part to single use zoning. Hence, they created few local jobs and residents commuted longer distances to work each day as the suburbs continued to expand.[2]

Cars in Popular Culture

The car had a significant effect on the culture of the middle class. As other vehicles had been, automobiles were incorporated into artworks including music, books and movies. Between 1905 and 1908, more than 120 songs were written in which the automobile was the subject.[8] Although authors such as Booth Tarkington decried the automobile age in books including The Magnificent Ambersons (1918), novels celebrating the political effects of motorization included Free Air (1919) by Sinclair Lewis, which followed in the tracks of earlier bicycle touring novels. Some early 20th century experts doubted the safety and suitability of allowing female automobilists. Dorothy Levitt was among those eager to lay such concerns to rest, so much so that a century later only one country had a women to drive movement. Where 19th century mass media had made heroes of Casey Jones, Allan Pinkerton and other stalwart protectors of public transport, new road movies offered heroes who found freedom and equality, rather than duty and hierarchy, on the open road.

George Monbiot writes that widespread car culture has shifted voter's preference to the right of the political spectrum.[16] He thinks that car culture has contributed to an increase in individualism and fewer social interactions between members of different socioeconomic classes.

As tourism became motorized, individuals, families and small groups were able to vacation in distant locations such as national parks. Roads including the Blue Ridge Parkway were built specifically to help the urban masses experience natural scenery previously seen only by a few. Cheap restaurants and motels appeared on favorite routes and provided wages for locals who were reluctant to join the trend to rural depopulation.

Since the early days of the automobile, the American Motor League promoted the making of more and better cars, and the American Automobile Association joined the good roads movement begun during the earlier bicycle craze. When manufacturers and petroleum fuel suppliers were well established, they also joined construction contractors in lobbying governments to build public roads.[2]

Road building was sometimes also influenced by Keynesian-style political ideologies. In Europe, massive freeway building programs were initiated by a number of social democratic governments after World War II, in an attempt to create jobs and make the automobile available to the working classes. From the 1970s, promotion of the automobile increasingly became a trait of some conservatives. Margaret Thatcher mentioned a "great car economy" in the paper on Roads for Prosperity.

Cars as a hobby

Over time, the car has evolved beyond being a means of transportation or status symbol and into a subject of interest and a cherished hobby amongst many people in the world, who appreciate cars for their craftsmanship, their performance, as well as the vast arrays of activities one can take part in with his/her car.[17] People who have a keen interest in cars and/or participate in the car hobby are known as "Car Enthusiasts".

One major aspect of the hobby is collecting, cars, especially classic vehicles, are appreciated by their owners as having aesthetic, recreational and historic value. [18]. Such demand generates investment potential and allows some cars to command extraordinarily high prices and become financial instruments in their own right.

Another major aspect of the hobby is driving events, where enthusiasts from around the world gather to drive and race their cars. Notable examples such events are the annual Mille Miglia classic car rally and the Gumball 3000 supercar race.

Many car clubs have been set up to facilitate social interactions and companionships amongst those who take pride in owning, maintaining, driving and showing their cars. Many prestigious social events around the world today are centered around the hobby, a notable example is the Pebble Beach Concours D'Elegance classic car show.

Safety

Motor vehicle accidents account for 37.5% of accidental deaths in the United States, making them the country's leading cause of accidental death.[19] Though travelers in cars suffer fewer deaths per journey, or per unit time or distance, than most other users of private transport such as bicyclers or pedestrians [citation needed], cars are also more used, making automobile safety an important topic of study.

Costs

In countries such as the United States the infrastructure that makes car use possible, such as highways, roads and parking lots is funded by the government and supported through zoning and construction requirements.[20] Fuel taxes in the United States cover about 60% of highway construction and repair costs, but little of the cost to construct or repair local roads.[21][22] Payments by motor-vehicle users fall short of government expenditures tied to motor-vehicle use by 20–70 cents per gallon of gas.[23] Zoning laws in many areas require that large, free parking lots accompany any new buildings. Municipal parking lots are often free or do not charge a market rate. Hence, the cost of driving a car in the US is subsidized, supported by businesses and the government who cover the cost of roads and parking.[20]

This government support of the automobile through subsidies for infrastructure, the cost of highway patrol enforcement, recovering stolen cars, and many other factors makes public transport a less economically competitive choice for commuters when considering Out-of-pocket expenses. Consumers often make choices based on those costs, and underestimate the indirect costs of car ownership, insurance and maintenance.[21] However, globally and in some US cities, tolls and parking fees partially offset these heavy subsidies for driving. Transportation planning policy advocates often support tolls, increased fuel taxes, congestion pricing and market-rate pricing for municipal parking as a means of balancing car use in urban centers with more efficient modes such as buses and trains.

When cities charge market rates for parking, and when bridges and tunnels are tolled, driving becomes less competitive in terms of out-of-pocket costs. When municipal parking is underpriced and roads are not tolled, most of the cost of vehicle usage is paid for by general government revenue, a subsidy for motor vehicle use. The size of this subsidy dwarfs the federal, state, and local subsidies for the maintenance of infrastructure and discounted fares for public transportation.[21]

By contrast, although there are environmental and social costs for rail, there is a very small impact.[21]

In the United States, out of pocket expenses for car ownership can vary considerably based on the state in which you live. In 2013, annual car ownership costs including repair, insurance, gas and taxes were highest in Georgia ($4,233) and lowest in Oregon ($2,024) with a national average of $3,201. [24]

Data provided by the AAA indicates cost of ownership in the United States is rising about 2% per year. [25]

See also

Alternatives

- Car-free movement

- Congestion pricing

- Freeway and expressway revolts

- Good Roads Movement

- Green vehicle

- Road protest in the United Kingdom

- Road space rationing

- New Pedestrianism

Effects

Planning response

References

Notes

- ^ The ‘System’ of Automobility by John Urrey. Theory, Culture & Society, Vol. 21, No. 4-5, 25-39 (2004)

- ^ a b c Asphalt Nation: how the automobile took over America, and how we can take it back By Jane Holtz Kay Published 1998 ISBN 0-520-21620-2

- ^ Gilbert, Alan (1996). The mega-city in Latin America. United Nations University Press. ISBN 92-808-0935-0.

- ^ "Madagascar: The Development of a National Rural Transport Program". Worldbank.org. 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ "''China Through a Lens: Rural Road Construction Speeded Up''". China.org.cn. 2003-05-16. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Joseph M.D. McCormick, Susan Fisher-Hoch and Leslie Alan Horvitz, Virus Hunters of the CDC, Turner Publishing (April 1997) IS 978-1570363979

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/sustainable/doc/2008_costs_handbook.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Kenneth T. (1985). Crabgrass frontier: The suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504983-7. OCLC 11785435.

- ^ Sidewalks? Too Pedestrian by: Mary Jane Smetanka Minneapolis-St Paul Star Tribune, Aut 18, 2007

- ^ Lots of Parking: Land Use in a Car Culture By John A. Jakle, Keith A. Sculle. 2004. ISBN 0-8139-2266-6

- ^ When Work Disappears by William Julius Wilson. ISBN 0-679-72417-6

- ^ Carriage trade The Free Dictionary

- ^ Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash, Owl Books, 355 pages (1999) ISBN 080506512

- ^ Smith, Robert (1972). A Social History of the Bicycle, its Early Life and Times in America. American Heritage Press.

- ^ From Highway to Superhighway: The Sustainability, Symbolism and Situated Practices of Car Culture Graves-Brown. Social Analysis. Vol. 41, pp. 64-75. 1997.

- ^ George Monbiot (2005-12-20). "George Monbiot, ''The Guardian'', December 20, 2005". London: Politics.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ http://www.aaca.org/About-AACA/an-introduction-to-aaca.html. A Concise History of AACA in the Beginning. Antique Automobile Club of America. Retrieved on February 20, 2014

- ^ http://www.wealthdaily.com/articles/investing-in-classic-cars/4748. Investing in classic cars. Retrieved on April 5, 2014

- ^ Directly from: http://www.benbest.com/lifeext/causes.html See Accident as a Cause of Death

Derived from: National Vital Statistics Report, Volume 50, Number 15 (September 2002) - ^ a b The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C. Shoup

- ^ a b c d Graph based on data from Transportation for Livable Cities By Vukan R. Vuchic page. 76. 1999. ISBN 0-88285-161-6

- ^ MacKenzie, J.J., R.C. Dower, and D.D.T. Chen. 1992. The Going Rate: What It Really Costs to Drive. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- ^ http://www.its.ucdavis.edu/people/faculty/delucchi

- ^ Car-ownership costs by state. Retrieved 2013-08-22

- ^ Which state is the most expensive for driving?. Retrieved 2013-08-22