Societal effects of cars

Since the start of the twentieth century, the role of cars has become highly important, though controversial. They are used throughout the world and have become the most popular mode of transport in many of the more developed countries. In developing countries cars are fewer and the effects of the car on society are less visible, however they are nonetheless significant. The spread of cars built upon earlier changes in transport brought by railways and bicycles. They introduced sweeping changes in employment patterns, social interactions, infrastructure and the distribution of goods.

Automobiles provide easier access to remote places and mobility, in comfort, helping people to geographically widen their social and economic interactions. Negative effects of the car on everyday life are also significant. Although the introduction of the mass-produced car represented a revolution in industry and convenience,[1][2] creating job demand and tax revenue, the high motorisation rates also brought severe consequences to the society and to the environment.

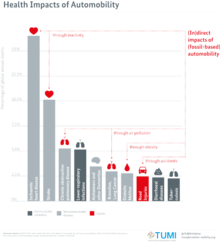

The modern negative associations with heavy automotive use include the use of non-renewable fuels, a dramatic increase in the rate of accidental death, the disconnection of local community,[3][4] the decrease of local economy,[5] the rise in cardiovascular diseases, the emission of air and noise pollution, the emission of greenhouse gases, generation of urban sprawl and traffic, segregation of pedestrians and other active mobility means of transport, decrease in the railway network, urban decay, and the high cost per unit-distance of private transport.[6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Since many people don't have cars, the resulting inequality intensifies structural inequalities and causes irreparable damage to the environment. Hence, neglecting the negative externalities of private automobility is irresponsible, and replacing combustion engine vehicles with EVs is merely a strategy to lose more slowly from social and environmental points of view.[13]

History

[edit]

In the early 20th century, cars entered mass production. The United States produced 45,000 cars in 1907, but 28 years later, in 1935, that had increased nearly 90-fold to 3,971,000.[14][better source needed] The increase in production required a large new workforce. In 1913, 14,366 people worked for the Ford Motor Company, and by 1916 that had increased to 132,702.[15] Bradford DeLong, an economic historian, noted that "Many more lined up outside the Ford factory for chances to work at what appeared to them to be, and (for those who did not mind the pace of the assembly line much) was an incredible boondoggle of a job".[14] There was a surge in the need for workers at big, new high-technology companies such as Ford. Employment increased greatly.

When the motor age arrived in Western countries at the beginning of the 20th century, many conservative intellectuals opposed the increase in motor traffic on the roads. The new vehicles removed space for pedestrians and made walking more dangerous, with car collisions becoming a major cause of pedestrian deaths.

W.S. Gilbert, the famous British librettist, wrote to The Times on 3 June 1903:

Sir,–I am delighted with the suggestion made by your spirited correspondent Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey that all pedestrians shall be legally empowered to discharge shotguns (the size of the shot to be humanely restricted to No. 8 or No. 9) At all motorists who may appear to them to be driven to the common danger. Not only would this provide a speedy and effective punishment for the erring motorist, but it would also supply the dwellers on popular high roads with a comfortable increase of income. "Motor shooting for a single gun" would appeal strongly to the sporting instincts of the true Briton, and would provide ample compensation to the proprietors of eligible road-side properties for the intolerable annoyance caused by the enemies of mankind.

Ten years later, Alfred Godley wrote a more elaborate protest, "The Motor Bus", a poem which cleverly combined a lesson in Latin grammar with an expression of distaste for the new form of motor transport.

Access and convenience

[edit]

Worldwide, the car has allowed easier access to remote places. More people have gone to live in those remote places and commute to work. The resulting traffic congestion and urban sprawl has brought an increase in average journey times in large cities, and the decommissioning of older tram systems.[16] Increases in air pollution and noise, and diminishing road safety, diminish the quality of life.[17][18]

Examples of car access issues in underdeveloped countries include the paving of Mexican Federal Highway 1 through Baja California, completing the connection of Cabo San Lucas to California. In Madagascar, about 30% of the population does not have access to reliable all-weather roads.[19] In China in 2003, 184 towns and 54,000 villages had no motor road (or roads at all).[20]

Certain developments in retail are partially due to car use, such as supermarket growth, drive-thru fast food purchasing, and gasoline station grocery shopping as well.

Economic changes

[edit]Employment and consumption habits

[edit]

The development of the car has contributed to changes in employment distribution, shopping patterns, social interactions, manufacturing priorities and city planning; increasing use of cars has reduced the roles of walking, horses and railroads.[21]

In addition to money for roadway construction, car use was also encouraged in many places through new zoning laws that required any new business to construct a certain amount of parking based on the size and type of facility. The effect was to create many free parking spaces, and business places further back from the road. In aggregate, this led to less dense settlements and made a carless lifestyle increasingly unattractive.

Retail parks attract revenue away from high streets and town centres. Many new shopping centers and suburbs did not install sidewalks,[22] making pedestrian access dangerous. This had the effect of encouraging people to drive, even for short trips that might have been walkable, thus increasing and solidifying American auto-dependency.[23] Opportunities for employment, activities, and housing widened for users, and narrowed for the carless.[24]

Economic growth

[edit]

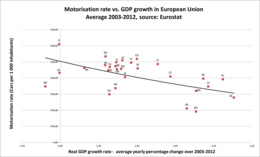

In countries with major car manufacturers, such as the United States or Germany, a certain degree of car dependency might be positive for the economy at a macroeconomic level, since it demands automobile production, therefore resulting also in job creation and tax revenues. These economic conditions were particularly valid during the 1920s when the number of automobiles, worldwide, was rapidly increasing, but also during the post–World War II economic expansion. Notwithstanding the growing effects provided by the automobile on the economy of some countries, countries specialize, exporting some products and importing others. Several auto-dependent countries, lacking an automobile industry and oil wells, must import vehicles and fuel, affecting their commercial balance. For example, the majority of European countries depend on imports of fossil fuels. Just few, such as Germany or France, manufacture enough cars to satisfy their country's demand for them. These factors affect the economic growth in the majority of European countries.[25][26]

Employment in the automotive industry

[edit]As of 2009 the U.S. motor vehicle manufacturing industry employed 880,000 workers, or approximately 6.5% of the U.S. manufacturing workforce.[27]

Traffic

[edit]Cycling steadily became more important in Europe over the first half of the 20th century, but it dropped off dramatically in the United States between 1900 and 1910. Automobiles became the dominant means of transportation. Over the 1920s, bicycles gradually became considered children's toys, and by 1940 most bicycles in the US were made for children.

From the early 20th century until after WWII, the roadster constituted most adult bicycles sold in the UK and in many parts of the British Empire. For many years after the advent of the motorcycle and automobile, they remained a primary means of adult transport.

Postwar

[edit]In several countries - both high and low income - bicycles have retained or regained this position. In Denmark, cycling policies were adopted as a direct consequence of the 1973 oil crisis, whereas bike advocacy in the Netherlands started in earnest with a campaign against traffic deaths called "stop child murder". Today both countries have high modal shares of cycling while also having high car ownership rates.

Cultural changes

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (December 2024) |

Affordable automobiles are sometimes said to have changed the world.

Modal split

[edit]Prior to the appearance of the automobile, the major modes of transportation within cities were horses, walking and (since the 19th century) streetcars.[21] Horses require a large amount of care, and were therefore kept in public facilities that were usually far from residences. The wealthy could afford to keep horses for private use, hence the term carriage trade referred to elite patronage.[28] Horse manure left on the streets also created a sanitation problem.[29]

Distance

[edit]The motorcycle made regular medium-distance travel more convenient and affordable and after World War I the automobile too, especially in areas without railways. Because cars did not require rest, were faster than horse-drawn conveyances, and soon had a lower total cost of ownership, more people were routinely able to travel farther than in earlier times. The construction of highways in the 1950s continued this. Some experts suggest that many of these changes began during the earlier Golden age of the bicycle, from 1880 to 1915.[30]

Changes to urban society

[edit]

Beginning in the 1940s, most urban environments in the United States lost their streetcars, cable cars, and other forms of light rail, to be replaced by diesel-run motor coaches or buses. Many of these have never returned, but some urban communities eventually installed rapid transit.

Another change brought about by the car is that modern urban pedestrians must be more alert than their ancestors. In the past, a pedestrian had to worry about relatively slow-moving streetcars or other obstacles of travel. With the proliferation of the car, a pedestrian has to anticipate safety risks of automobiles traveling at high speeds because they can cause serious injuries to a human and can be fatal,[21] unlike in previous times when traffic deaths were usually due to horses escaping control.

According to many social scientists, the loss of pedestrian-scale villages has also disconnected communities. Many people in developed countries have less contact with their neighbors and rarely walk unless they place a high value on walking. [citation needed]

Advent of suburban society

[edit]Following World War II in the United States, government policies and regulations such as the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, low-cost mortgages through the G.I. Bill, and residential redlining combined with white flight to foster the creation of suburbs. Suburban affluence led to a baby boomer generation far removed from the hardships of their parents. Community standards of the past, driven by scarcity and the need to share public resources, gave way to new credos of self-exploration. As the economy of the 1950s and 1960s boomed, car sales grew steadily, from 6,000,000 units sold per year in the United States to 10,000,000. Married women entered the workforce and two-car households with driveways and garages became commonplace. In the 1970s, however, the comparative economic stagnation then experienced was accompanied by societal self-reflection on the changes the motor car brought. Critics of automotive society found little positive choice in the decision to move to the suburbs; the physical movement was looked upon as flight. The automotive industry was also under attack from bureaucratic fronts, and new emission and CAFÉ regulations began to hamper Big Three (automobile manufacturers) profit margins as the United States went into a recession.

Kenneth R. Schneider in Autokind vs Mankind (1971) called for a war against the automobile, derided it for being a destroyer of cities, and likened its proliferation to a disease. In combination with his second book On the Nature of Cities (1979), he called for a struggle to halt and partially reverse negative developments in transportation, although he was largely ignored at the time.[31] Renowned social critic Vance Packard in A Nation of Strangers (1972) blamed the geographic mobility enabled by the auto for loneliness and social isolation. Automobile sales peaked in 1973, at 14.6 million units sold, and were not to reach comparable levels for another decade. The 1973 Arab-Israeli War was followed by the OPEC oil embargo, leading to an explosion of prices, long queues at filling stations, and talks of rationing fuel.

While it may appear clear, in retrospect, that the automotive/suburban culture would continue to persist, as it did in the 1950s and 1960s, no such certainty existed at the time when British architect Martin Pawley authored his seminal work, The Private Future (1973). Pawley called the automobile "the shibboleth of privatisation; the symbol and the actuality of withdrawal from the community" and perceived that, in spite of its momentary misfortunes, its dominance in North American society would continue. The car was a private world that allowed for fantasy and escape, and Pawley forecasted that it would grow in size, and in technological capacities. He saw no pathology in consumer behavior grounded in freedom of expression.

Improved transport accelerated the outward growth of cities and the development of suburbs beyond an earlier era's streetcar suburbs.[21] Until the advent of the car, factory workers lived either close to the factory or in high-density communities farther away, connected to the factory by streetcar or rail. The car and the federal subsidies for roads and suburban development that supported car culture allowed people to live in low density residential areas even farther from the city center and integrated city neighborhoods.[21] Industrial suburbs being few, due in part to single use zoning, they created few local jobs and residents commuted longer distances to work each day as the suburbs continued to expand.[7]

Cars in popular culture

[edit]United States

[edit]

The car had a significant effect on the culture of the United States. In American society, the automobile has traditionally played an important role in personal mobility and is often seen as a symbol of independence, individualism and freedom.[32][33][34] According to German business magazine Manager Magazin, the United States is considered "the car country par excellence", being the "homeland of drive-in restaurants, car cinemas and Route 66".[35]

As other vehicles had been, cars were incorporated into artworks including music, books and movies. Between 1905 and 1908, more than 120 songs were written in which the automobile was the subject.[21][failed verification] Although authors such as Booth Tarkington decried the automobile age in books including The Magnificent Ambersons (1918), novels celebrating the political effects of motorization included Free Air (1919) by Sinclair Lewis, which followed in the tracks of earlier bicycle touring novels. Some early 20th century experts doubted the safety and suitability of allowing female automobilists. Dorothy Levitt was among those who laid such concerns to rest, so much so that a century later there was only one country where women were forbidden to drive. Where 19th-century mass media had made heroes of Casey Jones, Allan Pinkerton and other stalwart protectors of public transport, new road movies offered heroes who found freedom and equality, rather than duty and hierarchy, on the open road.

George Monbiot writes that widespread car culture has shifted voter's preference to the right-wing of the political spectrum, and thinks that car culture has contributed to an increase in individualism and fewer social interactions between members of different socioeconomic classes.[36] The American Motor League had promoted the making of more and better cars since the early days of the car, and the American Automobile Association joined the good roads movement begun during the earlier bicycle craze; when manufacturers and petroleum fuel suppliers were well established, they also joined construction contractors in lobbying governments to build public roads.[7]

As tourism became motorized, individuals, families and small groups were able to vacation in distant locations such as national parks. Roads including the Blue Ridge Parkway were built specifically to help the urban masses experience natural scenery previously seen only by a few. Cheap restaurants and motels appeared on favorite routes and provided wages for locals who were reluctant to join the trend to rural depopulation.[citation needed]

Europe

[edit]

Road building was sometimes also influenced by Keynesian-style political ideologies. In Europe, massive freeway building programs were initiated by a number of social democratic governments after World War II, in an attempt to create jobs and make the car available to the working classes. From the 1970s, promotion of the automobile increasingly became a trait of some conservatives. Margaret Thatcher mentioned a "great car economy" in the paper on Roads for Prosperity.[citation needed] The 1973 oil crisis and with it fuel rationing measures brought to light for the first time in a generation, what cities without cars might look like, reinvigorating or creating environmental consciousness in the process. Green parties emerged in several European countries in partial response to car culture, but also as the political arm of the anti-nuclear movement.

Cinema

[edit]The rise of car culture during the twentieth century played an important cultural role in cinema, including in road movies and blockbusters. James Bond was seen in his Aston Martin DB5, and James Dean in other powerful automobiles. Some comedies and fantasies such as Susie the Little Blue Coupe, Go Trabi Go, Herbie, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and Cars (film) concentrated on the car as a character. Others such as A Racing Romeo, The Great Race, and Racing Dreams were about automobile racing.

Radio

[edit]With the advent of car radios, radio programming during rush hour became known as drive time. Music also references effects such as Big Yellow Taxi.

Cars as a lifestyle

[edit]

Over time, the car has evolved beyond being a means of transportation or status symbol and into a subject of interest and a cherished lifestyle amongst many people in the world, who appreciate cars for their craftsmanship, their performance, as well as the vast arrays of activities one can take part in with one's car.[37] People who have a keen interest in cars and/or participate in the car hobby are known as "Car Enthusiasts".

One major aspect of the hobby is collecting. Cars, especially classic vehicles, are appreciated by their owners as having aesthetic, recreational and historic value.[38] Such demand generates investment potential and allows some cars to command extraordinarily high prices and become financial instruments in their own right.[39]

A second major aspect of the car hobby is vehicle modification, as many car enthusiasts modify their cars to achieve performance improvements or visual enhancements. Many subcultures exist within this segment of the car hobby, for example, those building their own custom vehicles, primarily appearance-based on original examples or reproductions of pre-1948 US car market designs and similar designs from the World War II era and earlier from elsewhere in the world, are known as hot rodders, while those who believe cars should stay true to their original designs and not be modified are known as "Purists".

In addition, motorsport (both professional and amateur) as well as casual driving events, where enthusiasts from around the world gather to drive and display their cars, are important pillars of the car hobby as well. Notable examples of such events are the annual Mille Miglia classic car rally and the Gumball 3000 supercar race.

Many car clubs have been set up to facilitate social interactions and companionships amongst those who take pride in owning, maintaining, driving and showing their cars. Many prestigious social events around the world today are centered around the hobby, a notable example is the Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance classic car show.

Dedicated infrastructure

[edit]

- Automobile repair shop

- Billboard

- Car ferry

- Car wash

- Controlled-access highway

- Crash barrier

- Diner

- Drive-thru

- Drive-in theater

- Filling station

- Garage (residential)

- Motel

- Parking lot

- Retail park

- Roadside zoo

- Rest area

- Safari park

- Taxi rank

Safety and traffic collisions

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (October 2023) |

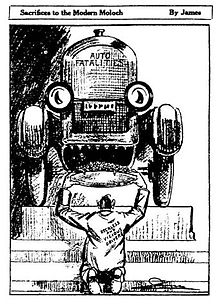

Motor vehicle accidents account for 37.5% of accidental deaths in the United States, making them the country's leading cause of accidental death.[44] Though travelers in cars suffer fewer deaths per journey, or per unit time or distance, than most other users of private transport such as bicyclers or pedestrians,[citation needed] cars are also more used, making automobile safety an important topic of study. For those aged 5–34 in the United States, motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death, claiming the lives of 18,266 Americans each year.[45][failed verification]

It is estimated that motor vehicle collisions caused the death of around 60 million people during the 20th century[46] around the same number of World War II casualties. Just in 2010 alone, 1.23 million people were killed due to traffic collisions.[47]

Notwithstanding the high number of fatalities, the trend of motor vehicle collision is showing a decrease. Road toll figures in developed nations show that car collision fatalities have declined since 1980. Japan is an extreme example, with road deaths decreasing to 5,115 in 2008, which is 25% of the 1970 rate per capita and 17% of the 1970 rate per vehicle distance travelled. In 2008, for the first time, more pedestrians than vehicle occupants were killed in Japan by cars.[48] Besides improving general road conditions like lighting and separated walkways, Japan has been installing intelligent transportation system technology such as stalled-car monitors to avoid crashes.

In developing nations, statistics may be grossly inaccurate or hard to get. Some nations have not significantly reduced the total death rate, which stands at 12,000 in Thailand in 2007, for example.[49] In the United States, twenty-eight states had reductions in the number of automobile crash fatalities between 2005 and 2006.[50] 55% of vehicle occupants 16 years or older in 2006 were not using seat belts when they crashed.[51] Road fatality trends tend to follow Smeed's law,[52] an empirical schema that correlates increased fatality rates per capita with traffic congestion.

Crime

[edit]Motoring offences and crimes related to cars include offences predating the automobile rather than exclusive to it. Many have become more prevalent with the rise of mass motoring.

- Car bomb

- Car theft

- Drive-by shooting

- DUI

- Jaywalking

- Parking violation

- Speeding

- Street racing

- Vehicular homicide

External and internal costs

[edit]

Public or external costs

[edit]According to the Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector[6] made by the Delft University and which is the main reference in European Union for assessing the externalities of cars, the main external costs of driving a car are:

- congestion and scarcity costs,

- accident costs,

- air pollution costs,

- noise costs,

- climate change costs,

- costs for nature and landscape,

- costs for water pollution,

- costs for soil pollution and

- costs of energy dependency.

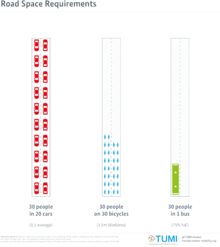

Use of cars for transportation creates barriers by reducing the landscape required for walking and cycling. It may look like a minor problem initially but in the long run, it poses a threat to children and the elderly. Transport is a major land use, leaving less land available for other purposes.

Cars also contribute to pollution of air and water. Though a horse produces more waste, cars are cheaper, thus far more numerous in urban areas than horses ever were. Emissions of harmful gases like carbon monoxide, ozone, carbon dioxide, benzene and particulate matter can damage living organisms and the environment. The emissions from cars cause disabilities, respiratory diseases, and ozone depletion. Noise pollution from cars can also potentially result in hearing disabilities, headaches, and stress to those frequently exposed to it.

In countries such as the United States the infrastructure that makes car use possible, such as highways, roads and parking lots is funded by the government and supported through zoning and construction requirements.[55] Fuel taxes in the United States cover about 60% of highway construction and repair costs, but little of the cost to construct or repair local roads.[56][57] Payments by motor-vehicle users fall short of government expenditures tied to motor-vehicle use by 20–70 cents per gallon of gas.[58] Zoning laws in many areas require that large, free parking lots accompany any new buildings. Municipal parking lots are often free or do not charge a market rate. Hence, the cost of driving a car in the US is subsidized, supported by businesses and the government who cover the cost of roads and parking.[55] This is in addition to other external costs car users do not pay like accidents or pollution. Even in countries with higher gas taxes like Germany motorists do not fully pay for the external costs they create.

This government support of the automobile through subsidies for infrastructure, the cost of highway patrol enforcement, recovering stolen cars, and many other factors makes public transport a less economically competitive choice for commuters when considering out-of-pocket expenses. Consumers often make choices based on those costs, and underestimate the indirect costs of car ownership, insurance and maintenance.[56] However, globally and in some US cities, tolls and parking fees partially offset these heavy subsidies for driving. Transportation planning policy advocates often support tolls, increased fuel taxes, congestion pricing and market-rate pricing for municipal parking as a means of balancing car use in urban centers with more efficient modes such as buses and trains.

When cities charge market rates for parking, and when bridges and tunnels are tolled, driving becomes less competitive in terms of out-of-pocket costs. When municipal parking is underpriced and roads are not tolled, most of the cost of vehicle usage is paid for by general government revenue, a subsidy for motor vehicle use. The size of this subsidy dwarfs the federal, state, and local subsidies for the maintenance of infrastructure and discounted fares for public transportation.[56]

By contrast, although there are environmental and social costs for rail, there is a very small footprint.[56]

Walking or cycling often have net positive effects on society as they help reduce health costs and produce virtually no pollution.

A study attempted to quantify the costs of cars (i.e. of car-use and related decisions and activity such as production and transport/infrastructure policy) in conventional currency, finding that the total lifetime cost of cars in Germany is between 0.6 and 1.0 million euros with the share of this cost born by society being between 41% (€4674 per year) and 29% (€5273 per year). This suggests that cars consume "a large share of disposable income", creating "complexities in perceptions of transport costs, the economic viability of alternative transport modes, or the justification of taxes".[59]

Private or internal costs

[edit]Compared to other popular modes of passenger transportation, especially buses or trains, the car has a relatively high cost per passenger-distance travelled.[60] For the average car owner, depreciation constitutes about half the cost of running a car,[61] nevertheless the typical motorist underestimates this fixed cost by a big margin, or even ignores it altogether.[62]

In the United States, out of pocket expenses for car ownership can vary considerably based on the state in which you live. In 2013, annual car ownership costs including repair, insurance, gas and taxes were highest in Georgia ($4,233) and lowest in Oregon ($2,024) with a national average of $3,201.[63] Furthermore, the IRS considers, for tax deduction calculations, that the automobile has a total cost for drivers in the US, of US$0.55/mile, around 0.26 EUR/km.[64] Data provided by the American Automobile Association indicates that the cost of ownership for an automobile in the United States is rising about 2% per year.[65] 2013 data provided by the Canadian Automobile Association concludes that the cost of ownership for a compact car in Canada, including depreciation, insurance, borrowing costs, maintenance, licensing, etc. was CA $9500 per year,[66] or about US$7300.

Consumer speed

[edit]The Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich, a critic of the modern society habits, was one of the first thinkers to establish the so-called consumer speed concept. He defined the term in his 1974 book Energy and Equity[67] as the distance that an average person commutes each year, divided by the amount of time dedicated to commuting and related activities. He calculated that the average American male spent 1,600 hours per year in car-related activities — about 28% of the time they spend awake — and traveled 7,500 miles (12,100 km) by car each year, giving a consumer speed of about 4.7 mph (7.6 km/h). In comparison, their contemporaries in developing countries spent less than 8% of their time walking. In other words, "[w]hat distinguishes the traffic in rich countries from the traffic in poor countries is not more mileage per hour of lifetime for the majority, but more hours of compulsory consumption of high doses of energy, packaged and unequally distributed by the transportation industry."[68]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bardou, J.-P.; Chanaron, J.-J.; Fridenson, P.; Laux, J. M. (30 November 1982). "THE AUTOMOBILE REVOLUTION--THE IMPACT OF AN INDUSTRY". Revue d'Économie Politique.

- ^ Davies, Stephen (1989). "Reckless Walking Must Be Discouraged". Urban History Review. 18 (2): 123–138. doi:10.7202/1017751ar. ISSN 0703-0428.

- ^ Kasarda, John D.; Janowitz, Morris (1974). "Community Attachment in Mass Society". American Sociological Review. 39 (3): 328–339. doi:10.2307/2094293. JSTOR 2094293.

- ^ Moss, Stephen (28 April 2015). "End of the car age: how cities are outgrowing the automobile". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Handy, Susan L.; Clifton, Kelly J. (1 November 2001). "Local shopping as a strategy for reducing automobile travel". Transportation. 28 (4): 317–346. doi:10.1023/A:1011850618753. ISSN 0049-4488. S2CID 153612928.

- ^ a b c M. Maibach; et al. (February 2008). "Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector" (PDF). Delft. p. 332. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Holtz Kay, Jane (1998). Asphalt Nation: how the automobile took over America, and how we can take it back. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21620-2.

- ^ Woodcock, James; Aldred, Rachel (21 February 2008). "Cars, corporations, and commodities: Consequences for the social determinants of health". Emerging Themes in Epidemiology. 5 (4): 4. doi:10.1186/1742-7622-5-4. PMC 2289830. PMID 18291031.

- ^ Gössling, Stefan; Kees, Jessica; Litman, Todd (1 April 2022). "The lifetime cost of driving a car". Ecological Economics. 194: 107335. Bibcode:2022EcoEc.19407335G. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107335.

- ^ Andor, Mark A.; Gerster, Andreas; Gillingham, Kenneth T.; Horvath, Marco (April 2020). "Running a car costs much more than people think — stalling the uptake of green travel". Nature. 580 (7804): 453–455. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..453A. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01118-w. PMID 32313129.

- ^ Williams, Ian D.; Blyth, Michael (1 February 2023). "Autogeddon or autoheaven: Environmental and social effects of the automotive industry from launch to present". Science of the Total Environment. 858 (Pt 3): 159987. Bibcode:2023ScTEn.85859987W. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159987. PMID 36372167.

- ^ Miner, Patrick; Smith, Barbara M.; Jani, Anant; McNeill, Geraldine; Gathorne-Hardy, Alfred (1 February 2024). "Car harm: A global review of automobility's harm to people and the environment". Journal of Transport Geography. 115: 103817. Bibcode:2024JTGeo.11503817M. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2024.103817. hdl:20.500.11820/a251f0b3-69e4-4b46-b424-4b3abea30b64.

- ^ Hosseini, Keyvan; Stefaniec, Agnieszka (2023). "A wolf in sheep's clothing: Exposing the structural violence of private electric automobility". Energy Research & Social Science. 99: 103052. Bibcode:2023ERSS...9903052H. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2023.103052. hdl:2262/102321. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ a b DeLong, Bradford. "The Roaring Twenties." Slouching Towards Utopia? The Economic History of the Twentieth Century". Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ Beaudreau, Bernard C. (2004). Mass Production, The Stock Market Crash, and The Great Depression: The Macroeconomics of Electrification. iUniverse. ISBN 9780595323340.

- ^ Gilbert, Alan (1996). The mega-city in Latin America. United Nations University Press. ISBN 978-92-808-0935-0.

- ^ "Get on the bus first to make Nicosia tram infrastructure worth the investment". European Investment Bank. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Cyprus third in EU for car ownership | Cyprus Mail". cyprus-mail.com/. 22 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Madagascar: The Development of a National Rural Transport Program". World Bank. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ "China Through a Lens: Rural Road Construction Speeded Up". China.org.cn. 16 May 2003. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Kenneth T. (1985). Crabgrass frontier: The suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504983-7. OCLC 11785435.

- ^ Smetanka, Mary Jane (18 August 2007). "Sidewalks? Too pedestrian for some". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ Jakle, John A.; Sculle, Keith A. (2004). Lots of Parking: Land Use in a Car Culture. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2266-6.

- ^ Wilson, William Julius (2011). When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-679-72417-9.

- ^ a b Motorisation Rate; Cars per 1000 inhabitants in Europe, Eurostat

- ^ a b Economic Growth, Real GDP growth rate - volume, Percentage change on previous year, Eurostat.

- ^ Michaela, Platzer; Glennon, Harrison. "The U.S. Automotive Industry: National and State Trends in Manufacturing Employment". Congressional Research Service.

- ^ Carriage trade The Free Dictionary

- ^ Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash, Owl Books, 355 pages (1999) ISBN 978-0-8050-6512-1

- ^ Smith, Robert (1972). A Social History of the Bicycle, its Early Life and Times in America. American Heritage Press.

- ^ Kenworthy, Jeffrey R. (2010). "Box. 8.7 Kenneth R. Schneider: Fighting for change". An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation: Policy, Planning and Implementation. London / Washington, D.C.: Earthscan / Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 9781136541940. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Humes, Edward (12 April 2016). "The Absurd Primacy of the Automobile in American Life". The Atlantic. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ D'Costa, Krystal. "Choice, Control, Freedom and Car Ownership". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ McAllister, Ted V. (14 October 2011). "Cars, Individualism, and the Paradox of Freedom in a Mass Society". Front Porch Republic. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Hecking, Mirjam (2 December 2013). "Sind die fetten Jahre vorbei?". www.manager-magazin.de (in German). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Monbiot, George (20 December 2005). "They call themselves libertarians; I think they're antisocial bastards". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ http://www.aaca.org/About-AACA/an-introduction-to-aaca.html Archived 30 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. A Concise History of AACA in the Beginning. Antique Automobile Club of America. Retrieved on 20 February 2014

- ^ "Investing in Classic Cars". www.wealthdaily.com. 23 October 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ "WSJ.com". www.wsj.com. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "Statistics database for transports". Eurostat (statistical database). Eurostat, European Commission. 20 April 2014. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Eksler, Vojtech, ed. (5 May 2013). "Intermediate report on the development of railway safety in the European Union 2013" (PDF). European Union Agency for Railways (report). Safety Unit, European Railway Agency & European Union. p. 1. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "OECD Data / Road Accidents". data.OECD.org. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 15 December 2023. Archived from the original on 6 July 2023.

- ^ Leonhardt, David (11 December 2023). "The Rise in U.S. Traffic Deaths / What's behind America's unique problem with vehicle crashes?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023.

- ^ Directly from: http://www.benbest.com/lifeext/causes.html See Accident as a Cause of Death

Derived from: National Vital Statistics Report, Volume 50, Number 15 (September 2002) - ^ "Data". Archived from the original on 23 November 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Pesce, Roberta (2 April 2013). "Death in the 20th Century. The Infographic". MedCrunch. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization. "Number of road traffic deaths".

- ^ Pedestrians become chief victims of road accident deaths in 2008 Archived 25 July 2009 at the Portuguese Web Archive

- ^ "365 Days for Stopping Accident Deaths". Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ People Killed in Motor Vehicle Crashes, by State, 2005-2006

- ^ NCSA Research Note (DOT-HS-810-948). US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. May 2008.

- ^ Adams, John. "Smeed's Law : some further thoughts" (PDF). University College London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ "Highlights of the Automotive Trends Report". EPA.gov. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 12 December 2022. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023.

- ^ Cazzola, Pierpaolo; Paoli, Leonardo; Teter, Jacob (November 2023). "Trends in the Global Vehicle Fleet 2023 / Managing the SUV Shift and the EV Transition" (PDF). Global Fuel Economy Initiative (GFEI). p. 3. doi:10.7922/G2HM56SV. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2023.

- ^ a b The High Cost of Free Parking by Donald C. Shoup

- ^ a b c d Graph based on data from Transportation for Livable Cities By Vukan R. Vuchic p. 76. 1999. ISBN 0-88285-161-6

- ^ MacKenzie, J.J., R.C. Dower, and D.D.T. Chen. 1992. The Going Rate: What It Really Costs to Drive[permanent dead link]. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

- ^ "Home".

- ^ Gössling, Stefan; Kees, Jessica; Litman, Todd (1 April 2022). "The lifetime cost of driving a car". Ecological Economics. 194: 107335. Bibcode:2022EcoEc.19407335G. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107335. ISSN 0921-8009. S2CID 246059536.

- ^

Diesendorf, Mark (2002). The Effect of Land Costs on the Economics of Urban Transportation Systems (PDF). American Society of Civil Engineers. pp. 1422–1429. ISBN 978-0-7844-0630-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Osborne, Hilary (20 October 2006). "Cost of running a car 'exceeds £5,000'". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Meek, James (20 December 2004). "The slow and the furious". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Car-ownership costs by state. Retrieved 22 August 2013

- ^ IRS (23 June 2011). "IRS Increases Mileage Rate to 55.5 Cents per Mile". Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- ^ Which state is the most expensive for driving?. Retrieved 22 August 2013

- ^ "CAA National". www.caa.ca. Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Illich, Ivan (1974). Energy and Equity (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015.

- ^ Illich, Ivan. "The industrialization of traffic".

excerpts from Energy and Equity; also collected in Toward a History of Needs