Etrog: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

The [[Romanization of Hebrew|romanization]] as ''Etrog'' is according to the [[Sephardic]] pronunciation, widely used in [[Israel]] through [[Modern Hebrew]]. The [[Ashkenazi]] pronunciation as in [[Yiddish]], is ''esrog'' or ''esrig''. Rarely it could also be [[transliterated]] as ''Ethrog'' or ''Ethrogh'' even in scholarly work, which is according to the [[Yemenite Hebrew]].<ref>[http://lib.ucr.edu/agnic/webber/Vol1/Chapter4.html#acid The Citrus Industry]</ref> The Hebrew word is thought to derive from the Persian name for the fruit, ''turung'', likely borrowed via Aramaic. |

The [[Romanization of Hebrew|romanization]] as ''Etrog'' is according to the [[Sephardic]] pronunciation, widely used in [[Israel]] through [[Modern Hebrew]]. The [[Ashkenazi]] pronunciation as in [[Yiddish]], is ''esrog'' or ''esrig''. Rarely it could also be [[transliterated]] as ''Ethrog'' or ''Ethrogh'' even in scholarly work, which is according to the [[Yemenite Hebrew]].<ref>[http://lib.ucr.edu/agnic/webber/Vol1/Chapter4.html#acid The Citrus Industry]</ref> The Hebrew word is thought to derive from the Persian name for the fruit, ''turung'', likely borrowed via Aramaic. |

||

<ref>[http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/jerusalem-dig-uncovers-earliest-evidence-of-local-cultivation-of-etrogs-1.410505]</ref> |

<ref>[http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/news/jerusalem-dig-uncovers-earliest-evidence-of-local-cultivation-of-etrogs-1.410505#acid Jerusalem dig uncovers earliest evidence of local cultivation of etrogs]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 09:06, 7 October 2014

Etrog (Template:Lang-he-n) refers to the yellow citron or Citrus medica used by Jews on the week-long holiday of Sukkot. While in modern Hebrew this is the name for any variety of citron, its English usage applies to those varieties and specimens used as one of the Four Species.[1]

Etymology

The romanization as Etrog is according to the Sephardic pronunciation, widely used in Israel through Modern Hebrew. The Ashkenazi pronunciation as in Yiddish, is esrog or esrig. Rarely it could also be transliterated as Ethrog or Ethrogh even in scholarly work, which is according to the Yemenite Hebrew.[2] The Hebrew word is thought to derive from the Persian name for the fruit, turung, likely borrowed via Aramaic. [3]

Biblical references

And you shall take on the first day the fruit of beautiful trees, branches of palm trees and boughs of leafy trees and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God 7 days!" -- Leviticus 23:40

Rabbinic Judaism sees the Biblical phrase peri eitz hadar (פְּרִי עֵץ הָדָר) as referring to the etrog. Grammatically, the Hebrew phrase is ambiguous; it is typically translated as "fruit of a beautiful tree," but it can also be read as "a beautiful fruit of a tree," which helps explain the great care with which etrogs are selected for performing the Sukkot holiday rituals.

Linguistic

In modern Hebrew, hadar refers to the genus Citrus. Nahmanides (1194 – c. 1270) suggests that the word was the original Hebrew name for the citron. According to him, the word etrog was introduced over time, adapted from the Aramaic. The Arabic name for the citron fruit, itranj (اترنج), mentioned in hadith literature, is also associated with the Hebrew.

Cosmetic requirements

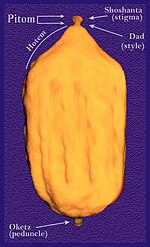

Pitam (Pitom)

A pitam is composed of a style (Hebrew: "דַד"), and a stigma (Hebrew: "שׁוֹשַׁנְתָּא"), and usually falls off during the growing process. An etrog with an intact pitam is considered especially valuable, but varieties that naturally shed off their pitam during growth are also considered kosher. When only the stigma breaks off, even post-harvest, the citron can still be considered kosher as long as part of the style has remained attached. If the whole pitam i.e. the stigma and style, are unnaturally broken off, all the way to the bottom, the etrog is not kosher for ritual use.

Many more pitams are preserved today thanks to an auxin discovered by Dr. Eliezer E. Goldschmidt, formerly professor of horticulture at the Hebrew University. Working with the picloram hormone in a citrus orchard, he discovered, to his surprise, that some of the Valencia oranges found nearby had preserved perfect pitams. Citrus fruits, other than an etrog or citron hybrid like the bergamot, usually do not preserve their pitam. When they occasionally do, it would at least be dry, sunken and very fragile. In this case the pitams were all fresh and solid just like those of the Moroccan or Greek citron varieties. Experimenting with picloram in a laboratory, Goldschmidt eventually found the correct “dose” to achieve the desired effect: one droplet of the chemical in three million drops of water. This invention is highly appreciated by the religious Jewish community.[4]

Purity

In order for a citron to be kosher, it must be neither grafted nor hybridized with any other species. Only a few traditional varieties are therefore used. To ensure that no grafting is used, the plantations are kept under strict rabbinical supervision.

Genetic research

| Citron varieties |

|---|

|

| Acidic-pulp varieties |

| Non-acidic varieties |

| Pulpless varieties |

| Citron hybrids |

| Related articles |

The citron varieties traditionally used as Etrog, are the Diamante Citron from Italy, the Greek Citron, the Balady Citron from Israel, the Moroccan and Yemenite Citrons.

A general DNA study was arranged by the world-renowned researcher of the etrog, Prof. Eliezer E. Goldschmidt and colleagues, who positively testified 12 famous accessions of citron for purity and being genetically related. As they clarify in their joint publication, this is only referring to the genotypic information which could be changed by breeding for e.g. out cross pollination etc., not about grafting which is not suspected to change anything in the genes.[5]

The Fingered and Florentine Citrons although they are also Citron varieties or maybe hybrids, are not used for the ritual. The Corsican Citron is no longer in use, though it was once used and sacred.

Selection and cultivation

In addition to the above, there are many rabbinical indicators to identify pure etrogs out of possible hybrids. Those traditional specifications were preserved by continuous selections accomplished by professional farmers.[6]

The most accepted indicators are as following: 1) a pure etrog has a thick rind, in contrast to its narrow pulp segments which are also almost dry, 2) the outer surface of an etrog fruit is ribbed and warted, and 3) the etrog peduncle is somewhat buried inward; a lemon or different citron hybrid is opposing one or all of the specifications.[7]

A later and not so widely accepted indicator is the orientation of the seed, which should be pointing vertically by an etrog, except if it was strained by its neighbors; by a lemon and hybrids they are positioned horizontally even when there is enough space.[8]

The etrog is typically grown from cuttings that are two to four years old, the tree begins to bear fruit when it is around four years old.[9] If the tree germinates from seeds, it will not fruit for about seven years, and there may be some genetic change to the tree or fruit in the event of seed propagation.[10]

Customs

To protect the etrog during the holiday, it is traditionally wrapped in silky flax fibers and stored in a special box, often made from silver. After the holiday, eating from the etrog or etrog jam is considered a segula (efficacious remedy) for a woman to have an easy childbirth.[11] A common Ashkenazi custom is to save the etrog until Tu Bishvat and eat it in candied form or as succade, accompanied by prayers that the worshiper will merit a beautiful etrog next Sukkot.[12] Some families make jam or liqueur out of it,[13] or stick cloves in the skin for use as besamim at the havdalah ceremony after Shabbat. The Dancing Camel Brewery in Tel Aviv, Israel, uses the rinds of etrogim in its annual 'Trog Wit Beer, usually available around the Holiday of Sukkot.[14]

Gallery

Etrog Gallery

|

References

- ^ Etrog page by the CVC of UCR

- ^ The Citrus Industry

- ^ Jerusalem dig uncovers earliest evidence of local cultivation of etrogs

- ^ Style Abscission in the Citron. American Journal of Botany, Vol. 58, no 1. pp. 14-23

- ^ A brief documentation of this study could be found at the Global Citrus Germplasm Network.

- ^ Article by Professor Goldschmidt, published by Tehumin, summer 5741 (1981), booklet 2, p. 144

- ^ Letter by rabbi Shmuel Yehuda Katzenellenbogen of Padua midst the 16th century, printed in Teshuvat ha'Remo chapter 126

- ^ Shiurey Kneseth Hagdola and Olat Shabbat, cited by Magen Avraham, Orach Chaim chapter 648, comment 23

- ^ Chiri, Alfredo. (2002). Etrog

- ^ Sunkist Website

- ^ Weisberg, Chana (2004). Expecting Miracles: Finding meaning and spirituality in pregnancy through Judaism. Urim Publications. p. 134. ISBN 9657108519.

- ^ Aish

- ^ Etrog recipes (link no longer valid)

- ^ 'Trog Wit

Further reading

- Citrus Propagation by Ultimate Citrus

- Fact Sheet HS-86 June 1994 by the University of Florida

- CROP PROPAGATION II: SEXUAL PROPAGATION

External links

- First evidence of the etrog tree in Israel

- The Citrus Variety Collection by the University of California Riverside

- Ancient Treasures and the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Mosaic depicting an etrog

- Lulav, Etrog, Shofar and Menorah, 2nd Cent. CE, Ostia Synagogue

- An antique Hebrew coin depicting an etrog

- Pictures homecitrusgrowers.co.uk

- Evyatar Marienberg and David Carpenter, The Stealing of the ‘Apple of Eve’ from the 13th century Synagogue of Winchester, Henri III Fine Rolls Project, Fine of the Month: December 2011

- A Huge Etrog-looking Citron in Geetha's Kitchen, amazing photos

- Know Your Etrog, website with educational pictures, information how to plant your own tree.