Jiaolong: Difference between revisions

m →References: HTTP→HTTPS for The New York Times. using AWB |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.3beta8) |

||

| Line 92: | Line 92: | ||

*Schafer, Edward H. 1973. ''The Divine Woman: Dragon Ladies and Rain Maidens in T'ang Literature''. University of California Press. |

*Schafer, Edward H. 1973. ''The Divine Woman: Dragon Ladies and Rain Maidens in T'ang Literature''. University of California Press. |

||

*Schuessler, Axel. 2007. ''ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese''. University of Hawaii Press. |

*Schuessler, Axel. 2007. ''ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese''. University of Hawaii Press. |

||

*Visser, Marinus Willern de. 1913. [http://fax.libs.uga.edu/GR830xD7xV8/# ''The Dragon in China and Japan'']. J. Müller. |

*Visser, Marinus Willern de. 1913. [https://web.archive.org/web/20081026155019/http://fax.libs.uga.edu/GR830xD7xV8/## ''The Dragon in China and Japan'']. J. Müller. |

||

*Watson, Burton, tr. 1968. ''The Complete works of Chuang Tzu''. Columbia University Press. |

*Watson, Burton, tr. 1968. ''The Complete works of Chuang Tzu''. Columbia University Press. |

||

Revision as of 09:22, 22 April 2017

Jiaolong (simplified Chinese: 蛟龙; traditional Chinese: 蛟龍; pinyin: jiāolóng; Wade–Giles: chiao-lung) or jiao is a polysemous aquatic dragon in Chinese mythology. Edward H. Schafer describes the jiao:

Spiritually akin to the crocodile, and perhaps originally the same reptile, was a mysterious creature capable of many forms called the chiao (kău). Most often it was regarded as a kind of lung – a "dragon" as we say. But sometimes it was manlike, and sometimes it was merely a fish. All of its realizations were interchangeable. (1967:217-8)

A doctor drawing out a river jiaolong with realgar during the race to preserve the body of Qu Yuan is traditionally credited with originating the practice of drinking realgar wine during the Dragon Boat Festival.

Name

蛟 Character

In traditional Chinese character classification, jiao 蛟 is a "radical-phonetic" or "phono-semantic character", combining the "insect radical" 虫 with a jiao 交 "cross; mix; mingle; mate with; exchange" phonetic. This 虫 radical is frequently used in characters for insects, worms, and reptiles, and occasionally for dragons (e.g., shen 蜃 and hong 虹). This phonetic jiao 交 (originally a pictograph of a person with crossed legs) is also used with the "fish radical" 魚 in jiao 鲛 "shark" (see below) and the "horse radical" 馬 in bo 駮, which is a variant Chinese character for bo 駁 "mixed colors; piebald; confused".

In the Japanese writing system, the kanji 蛟 can be read mizuchi "a Japanese river dragon" in native kun'yomi or kō in Sino-Japanese on'yomi (e.g., kōryō 蛟竜 "flood dragon: hidden genius" from jiaolong).

Etymology

Jiao's (蛟) etymology is obscure. Carr, using Bernhard Karlgren's reconstruction of Old Chinese *kǒg 蛟, explains.

Most etymologies for jiao < *kǒg 蛟 are unsupported speculations upon meanings of its phonetic *kǒg 交 'cross; mix with; contact', e.g., the *kǒg 蛟 dragon can *kǒg 交 'join' its head and tail in order to capture prey, or moves in a *kǒg 交 'twisting' manner, or has *kǒg 交 'continuous' eyebrows. The only corroborated hypothesis takes *kǒg 交 'breed with' to mean *kǒg 蛟 indicates a dragon 'crossbreed; mixture'. Eberhard (1968:378) notes from an early time, 蛟 was considered an embodiment of the fish, snake, rhinoceros; or the tiger. (1990:126-7)

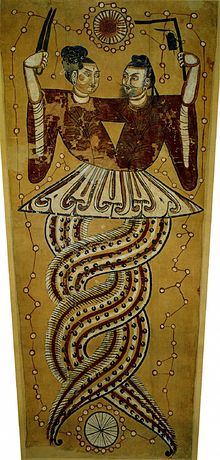

Compare the "tiger jiao" below. In addition, Carr cites Wen Yiduo that jiaolong 交龍 "crossed dragons"' or jiaolong 蛟龍 were emblems of the mythological creators Fuxi and Nüwa, who are represented as having a human's upper body and a dragon's tail.

Schuessler (2007:308) reconstructs modern jiāo 蛟 "scaly dragon", "alligator", or "mermaid" as Middle Chinese kau and Old Chinese *krâu. He suggests possible Tibeto-Burman etymological connections with Burmese khruB or khyuB "mermaid; serpent" and Tibetan klu "nāga; water spirits".

Usage

Chinese jiao 蛟 is more frequently used in the compound jiaolong with the -long 龍 "dragon" suffix than by itself. Take, for example, familiar chengyu "set phrases; 4-character idioms". Jiaolong occurs in several such as jiaolongdeshui 蛟龍得水 (lit. jiao-dragon obtains water", from the Guanzi below) "in the most congenial surroundings; bold person getting a good opportunity" and jiaolongzhizhi 蛟龍之志 (jiao-dragon's ambition") "a person with great ambitions". Jiao occurs abbreviating jiaolong with feng abbreviating fenghuang 鳳凰 "Chinese phoenix" in tengjiaoqifeng 騰蛟起鳳 ("soaring jiao rising feng") "a rapidly rising literary/artistic talent; a genius".

Jiaolong occurs in Chinese toponyms. For example, the highest waterfall in Taiwan is Jiaolong Dapu 蛟龍大瀑 "Flood Dragon Great Waterfall" in the Alishan National Scenic Area.

The deep-sea submersible built and tested in 2010 by the China Ship Scientific Research Center is named Jiaolong (Broad 2010:A1).

Meanings

"Jiao < *kǒg 蛟 is defined with more meanings than any other Chinese draconym", writes Carr (1990:126), "(1) 'aquatic dragon', (2) 'crocodile; alligator', (3) 'hornless dragon', (4) 'dragoness', (5) 'scaled dragon', ( 6 ) 'shark' [= 鮫], and (7) 'mermaid'."

In some textual usages, differentiating these jiao meanings is problematic. For instance, jiaolong 蛟龍 can be parsed as two kinds of dragons or one. Some contrastive contexts clearly use the former meaning "jiao and long dragons"; the Zhuangzi (17, tr. Watson 1968:185) parallels "the sea serpent or the dragon" with "the rhinoceros or the tiger." The latter meaning of "jiao dragon" is evident from usages such as the Guanzi (1, tr. Visser 1913:77), "The kiao-lung is the god of the water animals. If he rides on the water, his soul is in full vigour, but when he loses water (if he is deprived of it), his soul declines. Therefore I (or they) say: 'If a kiao-lung gets water, his soul can be in full vigour'."

Schafer notes the problems with translating jiao as "dragon".

The word "dragon" has already been appropriated to render the broader term lung. "Kraken" is good since it suggests a powerful oceanic monster. ... We might name the kău a "basilisk" or a "wyvern" or a "cockatrice." Or perhaps we should call it by the name of its close kin, the double-headed crocodile-jawed Indian makara, which, in ninth-century Java at least, took on some of the attributes of the rain-bringing lung of China. (1967:218)

Aquatic dragon

Jiao and jiaolong were names for a legendary river dragon.

The mythological Shanhaijing "Classic of Mountains and Seas" mentions jiao and hujiao 虎蛟 "tiger jiao", but notably not jiaolong. The "Classic of Southern Mountains" (1, Visser 1913:76) records hujiao in the Yin River 泿水.

The River Bank rises here and flows south to empty into the sea. There are tiger-crocodiles in it. Their bodies look like a fish's, but they have a snake's tail and they make a noise like mandarin ducks. If you eat some, you won't suffer from a swollen abscess, and it can be used to treat piles. (tr. Birrell 2000:8)

The commentary of Guo Pu glosses hujiao as "a type of [long 龍] dragon that resembles a four-legged snake." The "Classic of Central Mountains" (5, tr. Birrell 2000:93, 97) records jiao in the Kuang River 貺水 and Lun River 淪水: "There are numerous alligators in the River Grant" and "The River Ripple contains numbers of alligators". Guo adds that the jiao "has a small head, narrow neck, white scales, is oviparous, can grow up to ten meters long, and eats people."

Wolfram Eberhard (1968:378) quotes the (11th century CE) Moke huixi 墨客揮犀 for the "best definition" of a jiao, "looks like a snake with a tiger head, is several fathoms long, lives in brooks and rivers, and bellows like a bull; when it sees a human being it traps him with its stinking saliva, then pulls him into the water and sucks his blood from his armpits." He concludes (1968:378-9) that the jiao, which "occur in the whole of Central and South China", "is a special form of the snake as river god. The snake as river god or god of the ocean is typical for the coastal culture, particularly the sub-group of the Tan peoples."

Jiao 蛟 is sometimes translated as "flood dragon". The (c. 1105 CE) Yuhu qinghua 玉壺清話 (Carr 1990:128) says people in the southern state of Wu called it fahong 發洪 "swell into a flood" because they believed flooding resulted when jiao hatched. The Chuci (13, tr. Hawkes 1985:255) uses the term shuijiao 水蛟 "water jiao": "Henceforth the water-serpents must be my companions, And dragon-spirits lie with me when I would rest."

Crocodile or Alligator

Besides a legendary dragon, jiao and jiaolong anciently named a four-legged water creature, identified as both "alligator" and "crocodile". The "Dragons and Snakes" section of the (1578 CE) Bencao Gangmu, which is a comprehensive Chinese materia medica, differentiates (tr. Read 1934:314-318) between jiaolong 蛟龍 (or e 鱷) "Saltwater Crocodile, Crocodylus porosus" and tolong 鼉龍 "Chinese Alligator, Alligator sinensis". Most early references describe the jiaolong as living in rivers, which fits not only this freshwater "Chinese alligator" but also the "Saltwater crocodile" that spends the tropical wet season in freshwater rivers and swamps. Comparing maximum lengths of 8 and 1.5 meters for this crocodile and alligator respectively, "Saltwater crocodile" seems more consistent with descriptions of jiao reaching lengths of several zhang 丈 "approximately 3.3 meters".

Three classical texts (Liji 6, tr. Legge 1885:1:277, Huainanzi 5, and Lüshi Chunqiu 6) repeat a sentence about capturing water creatures at the end of summer; 伐蛟取鼉登龜取黿 "attack the jiao 蛟, take the to 鼉 "alligator", present the gui 龜 "tortoise", and take the yuan 黿 "soft-shell turtle"."

Early texts frequently mention capturing jiao. The (ca. 111 CE) Hanshu (6, Carr 1990:128) records catching a jiao 蛟in 106 BCE. The (4th century CE) Shiyiji 拾遺記 has a jiao story about Emperor Zhao of Han (r. 87-74 BCE). While fishing in the Wei River, he

caught a white kiao, three chang [ten meters] long, which resembled a big snake, but had no scaly armour The Emperor said: 'This is not a lucky omen', and ordered the Ta kwan to make a condiment of it. Its flesh was purple, its bones were blue, and its taste was very savoury and pleasant. (tr. Visser 1913:79)

The historicity of such accounts can be dubious. The (ca. 109-91 BCE) Shiji biography of Emperor Gaozu of Han (r. 202-195 BCE) recounts a legend that his mother dreamed of a jiaolong before his birth.

Hornless dragon

The (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi dictionary defines jiao 蛟 as "A kind of dragon, a hornless dragon is called jiao. It explains that "if the number of fish in a pond reaches 3600, a jiao will come as their leader, and enable them to follow him and fly away." However, "if you place a fish trap in the water, the jiao will leave." According to the Chuci commentary of Wang Yi 王逸 (d. 158 CE), the jiao is a "hornless dragon" or a "small dragon", perhaps implying a young or immature dragon.

Note the pronunciation similarity between jiao 蛟 and jiao 角 "horn". Jiaolong 角龍 "horned dragon", which is the Chinese name for the Ceratops dinosaur, occurs in Ge Hong's Baopuzi (10, tr. Ware 1966:170) "the horned dragon can no longer find a place to swim."

Female dragon

Jiao meaning "female dragon; dragon mother" is first recorded in the (c. 807 CE) Buddhist dictionary Yiqiejing yinyi compiled by the monk Huilin 慧琳 (19). It defines jiaolong as "a fish with a snake's tail," notes the Sanskrit name guanpiluo 官毘羅 "kumbhīra; crocodile; alligator", and quotes Ge Hong's Baopuzi 抱朴子 that jiao 蛟 means "dragon mother, dragoness" and qiu 虯 "horned dragon" means "dragon child, dragonet". However, the received edition of the Baopuzi does not include this statement. The (11th century CE) Piya dictionary repeats this "female dragon" definition.

Scaly dragon

The (3rd century CE) Guangya defines jiaolong as "scaly dragon; scaled dragon", using the word lin 鱗 "scales (of a fish, etc.)". Many later dictionaries copied this meaning, but it lacks textual corroboration.

Shark

Jiao 蛟 was an interchangeable graphic loan character for jiao 鮫 "shark", usually called the jiaoyu 鮫魚 or shayu 鯊魚. Jiaoge 鮫革 (with ge "hide; leather") means "sharkskin". Several texts (Han shi waizhuan 韓詩外傳, Shangzi, Xunzi, Shiji, and Huainanzi) record that soldiers from the southern state of Chu made strong armor with skin from jiao sharks and hides from rhinoceros. Schafer (1973:26) suggests, "The Chinese lore about these southern krakens seems to have been borrowed from the indigenes of the monsoon coast."

Stingray

Jiao fish named both sharks and stingrays (see Elasmobranchii). Schafer (1967:221) quotes a Song Dynasty description, "The kău fish has the aspect of a round fan. Its mouth is square and is in its belly. There is a sting in its tail which is very poisonous and hurtful to men. Its skin can be made into sword grips."

Mermaid

Jiaoren 蛟人 "dragon person" or 鮫人 "shark person" (cf. Japanese samebito 鮫人) "mermaid" is a later meaning of jiao. This mythical southern mermaid or merman is first recorded in the (early 6th century CE) Shuyiji 遹異記 "Records of Strange Things".

In the midst of the South Sea are the houses of the kău people who dwell in the water like fish, but have not given up weaving at the loom. Their eyes have the power to weep, but what they bring forth is pearls. (tr. Schafer 1967:220, cf. Eberhard 1968:378)

These aquatic people supposedly spun a type of raw silk called jiaoxiao 蛟綃 "mermaid silk" or jiaonujuan 蛟女絹 "mermaid woman's silk". Schafer (1967:221) equates "jiao silk" with sea silk, the rare fabric woven from byssus filaments produced by Pinna "pen shell" mollusks. Chinese myths also recorded this "silk" coming from shuiyang 水羊 "water sheep" or shuican 蠶水 "water silkworm".

See also

- Mizuchi, a Japanese jiaolong

- Jiaolong (album), an album by DJ Daphni (musician)

References

- Birrell, Anne, tr. 2000. The Classic of Mountains and Seas. Penguin.

- Broad, William J., "China Explores a Frontier 2 Miles Deep", The New York Times, September 11, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- Carr, Michael. 1990. "Chinese Dragon Names", Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 13.2:87-189.

- Eberhard, Wolfram. 1968. The Local Cultures of South and East China. E. J. Brill.

- Hawkes, David, tr. 1985. The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Penguin.

- Legge, James, tr. 1885. The Li Ki, 2 vols. Oxford University Press.

- Read, Bernard E. 1934. "Chinese Materia Medica VII; Dragons and Snakes," Peking Natural History Bulletin 8.4:279-362.

- Schafer, Edward H. 1967. The Vermillion Bird: T'ang Images of the South. University of California Press.

- Schafer, Edward H. 1973. The Divine Woman: Dragon Ladies and Rain Maidens in T'ang Literature. University of California Press.

- Schuessler, Axel. 2007. ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press.

- Visser, Marinus Willern de. 1913. The Dragon in China and Japan. J. Müller.

- Watson, Burton, tr. 1968. The Complete works of Chuang Tzu. Columbia University Press.

External links

- 蛟 entry, Chinese Etymology

- 蛟 entry page, 1716 CE Kangxi Dictionary

- Flood Dragon Waterfall, Alishan National Scenic Area